HMS Hebrus

Plan of the Scamander-class frigates | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Hebrus |

| Namesake | River Hebrus |

| Ordered | 16 November 1812 |

| Laid down | January 1813 |

| Launched | 13 September 1813 |

| Completed | 18 December 1813 |

| Commissioned | October 1813 |

| Out of service | 2 November 1816 |

| Fate | Sold 3 April 1817 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type | Fifth-rate Scamander-class frigate |

| Tons burthen | 939 (bm) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 38 ft 4+1⁄2 in (11.7 m) |

| Draught |

|

| Depth of hold | 11 ft 11+3⁄4 in (3.7 m) |

| Propulsion | Sails |

| Complement | 284 |

| Armament |

|

HMS Hebrus was a 36-gun Scamander-class frigate of the Royal Navy. Constructed in response to the start of the War of 1812, Hebrus was commissioned in October 1813 under Captain Edmund Palmer. Serving initially in the English Channel, on 27 March 1814 the frigate fought at the Battle of Jobourg during which she captured the French 40-gun frigate Étoile in a single-ship action. Hebrus was subsequently transferred to serve in North America. She participated in the expedition up the Patuxent River in August which resulted in the destruction of the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla, and Palmer was also present at the Battle of Bladensburg.

Hebrus fought at the Battle of Baltimore in September as part of the squadron bombarding Fort McHenry and subsequently served off the coast of Georgia in the command of Rear-Admiral George Cockburn, being present at the capture of Cumberland Island and Battle of Fort Peter in January 1815. Hebrus returned to Britain in May carrying the body of Captain Sir Peter Parker for burial in London. In the Hundred Days campaign she was then employed off Bordeaux working to support French Royalists.

In the peace after the Napoleonic Wars Hebrus was part of the Cork Station before in July 1816 she joined Admiral Lord Exmouth's fleet that in August bombarded Algiers. After this the ship was surveyed and found to be extremely rotten. Hebrus was paid off in November and eventually sold in April 1817.

Design and construction

[edit]Hebrus was a 36-gun, 18-pounder Scamander-class frigate. The class was constructed as part of the reaction of Lord Melville's Admiralty to the beginning of the War of 1812. This new theatre of operations, with the Napoleonic Wars ongoing, was expected to put a strain on the existing fleet of Royal Navy frigates, and so more were needed to be built. Designed by the Surveyor of the Navy, Sir William Rule, the Scamander class was one of those put into construction to fill this need.[2] The class was a variant of the existing Apollo-class frigate, which had been the standard design for 36-gun frigates in the Royal Navy for over a decade.[3][4] The class was particularly copied from the lines of the 36-gun frigate HMS Euryalus.[5]

The war was expected to only be a short affair, and so ships built specifically for it were not designed for long service lives. As such Hebrus's class was ordered to be constructed out of the soft but easily available "fir". In actual fact this meant the use of red and yellow pine.[2] Using pine for construction meant that the usually long period of time between keel laying and launching could be dramatically decreased to as little as three months. Pine-built ships could usually be differentiated from those of oak by their flat "square tuck" stern, but as copies of oak-built ships the Scamander class did not have this feature.[5] The naval historian Robert Gardiner describes the class as an "austerity" version of the Apollos.[3][4]

The first seven ships of the Scamander class, six of which were ordered in May before the war had begun, were built with red pine. The final three, of which Hebrus was one, received yellow pine. All ships of the class were ordered to commercial shipyards rather than Royal Navy Dockyards, with the navy providing the pine for their construction from its own stocks.[2] Hebrus was ordered on 16 November 1812, to be built by the shipwright John Barton at Limehouse. The frigate was laid down in January of the following year, and launched on 13 September with the following dimensions: 143 feet (43.6 m) along the upper deck, 120 feet 1+1⁄8 inches (36.6 m) at the keel, with a beam of 38 feet 4+1⁄2 inches (11.7 m) and a depth in the hold of 11 feet 11+3⁄4 inches (3.7 m). The ship had a draught of 8 feet 8 inches (2.6 m) forward and 12 feet 10 inches (3.9 m) aft, and measured 939 tons burthen.[6][7] She was named after the River Hebrus.[8]

Pine was a lighter material than oak which allowed the ships to often sail faster than those built of the heavier wood, but this in turn meant that the ships required more ballast than usual to ensure that they sat at their designated waterline. Based on an oak-built design but with more ballast than that design was expected to carry, Hebrus and her class were designed with a distinctly shallower depth in the hold. This ensured that the frigates were not aversely affected by the excess ballast, which could cause them to be "over-stiff".[5]

Having already been coppered by Barton, the fitting out process for Hebrus was completed at Deptford Dockyard on 18 December.[6] The frigate originally had a crew complement of 274, but this was increased to 284 for the entire class on 26 January 1813, while she was still under construction. Hebrus held twenty-six 18-pounder long guns on her upper deck. Complimenting this armament were twelve 32-pounder carronades on the quarterdeck, with two 9-pounder long guns and two additional 32-pounder carronades on the forecastle.[2] Hebrus is often described as a 42-gun frigate rather than a 36-gun one.[9][10]

Service

[edit]Napoleonic Wars

[edit]

While completing her fitting out process, Hebrus was commissioned by Captain Edmund Palmer in October 1813.[6] The frigate was sent to serve in the English Channel.[11] On 23 January 1814 the French 40-gun frigates Étoile and Sultane battled two British frigates off the Cape Verde Islands inconclusively. They then made their way towards St Malo. On 26 March the French ships were sailing in heavy fog off Roscoff when they almost ran into the 16-gun sloop HMS Sparrow, subsequently engaging and disabling her. Hebrus, patrolling near by, closed on the scene and began to fire at the enemy frigates. The noise of the combat attracted the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Hannibal, which sailed towards Hebrus as the fog began to clear. Soon afterwards the wind changed direction and Étoile and Sultane began to separate themselves from the British.[12]

Sultane, which was already jury rigged from the action off the Cape Verde Islands, was quickly caught up with and captured by Hannibal at 3:15 p.m.[13] Hebrus was sent by Captain Sir Michael Seymour of Hannibal to chase Étoile with Sparrow. Hebrus soon outpaced Sparrow and closed with the French vessel, catching up with her as the latter passed through Alderney Race just after midnight.[12][14][10] By this time the wind had begun to falter and at 1:40 a.m. on 27 March Étoile fired at Hebrus as she passed close to the shore at Jobourg. Hebrus returned fire and sailed to get between the French vessel and the coastline.[10]

By 2 a.m. the duelling frigates were almost becalmed and in shoal water.[12] Étoile crossed in front of Hebrus at 2:20 a.m. to again get closer to the coast and fired into the latter's rigging, severely damaging it.[12][11][10] Despite this, at 3 a.m. Palmer took advantage of a slight breeze and manoeuvred Hebrus so that the frigate could rake her opponent.[12] Hebrus began firing at Étoile from a very close distance, with the two ships hardly moving. While the French vessel had aimed for rigging, Hebrus attacked Étoile's hull.[14] The latter withstood the fire until around 4 a.m. when her mizzenmast was shot away, at which point she surrendered.[12][11] This ended the Battle of Jobourg.[12]

A French gun battery had been blindly firing towards the two frigates in the darkness as they fought, and the crew of Hebrus quickly took control of their prize to take her out of range.[15][14] The two frigates found shelter in Vauville Bay, where they repaired what battle damage to their masts they could. Étoile's rigging and hull were both heavily damaged, and out of a crew of 320 she had forty killed and around seventy wounded. Hebrus's casualties were less but still severe, with thirteen killed and twenty-five wounded.[15]

War of 1812

[edit]In May Hebrus was assigned as an escort to the fleet transporting Major-General Robert Ross's reinforcements to serve in the War of 1812. They departed from Le Verdon-sur-Mer on 2 June and arrived at Bermuda in late July.[16] Hebrus then reached the Coan River on 7 August, escorting a Royal Marine Battalion, and joined a force under Rear-Admiral George Cockburn; Cockburn was operating ashore at the time, and Palmer had to personally track the admiral down in his barge to report his presence. The force sailed to St. Mary's Creek on 11 August.[17] By 16 August Hebrus was with Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane in Chesapeake Bay, where a large fleet had congregated for offensive operations.[18] Hebrus was then part of the force under Cockburn that served in operations on the Patuxent River, where the American Chesapeake Bay Flotilla was based, later in the month.[19][20]

They sailed up the river on 18 August, with an infantry force mirroring them on land. On 20 August the force reached Benedict, from where further travel was impossible for Hebrus and the other frigate on the operation, the 40-gun HMS Severn.[19][20][21] Palmer left the ship and joined Cockburn, who was with the smaller ships at Nottingham, with the frigate's boats.[20][22] American defence was initially non-existent, although an American cavalry patrol briefly fired on the advancing ships on 22 August.[19][20] The naval force out-distanced the infantry and soon after reached Queen Anne where the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla was; as they approached the American ships, rigged for demolition, began exploding. Of the flotilla, only one gunboat and thirteen merchant schooners were left to be captured.[23][14][20] Palmer was afterwards ordered ashore to support British Army operations, and was the only post-captain present at the victorious Battle of Bladensburg on 24 August, where he commanded a division of armed seamen.[23][14][24] He was the only member of Hebrus's crew there apart from his aide de camp, Midshipman Arthur Wakefield, as the majority of the naval contingent did not reach the battle in time.[25][26] After Washington was burned on the following day a storm began and at 2:30 p.m. it hit Benedict, where Hebrus and Severn were driven onto the shore;[27] it was recorded that the winds

"lashed the smooth and placid waters of the Patuxent into one vast sheet of foam, which covered both our rigging and the decks with its spray"[28]

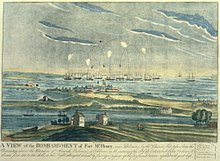

Hebrus subsequently joined a squadron of frigates and bomb vessels commanded by Captain James Gordon, that was intended to attack Baltimore from the sea in the upcoming Battle of Baltimore. Having arrived two days earlier, on 12 September the squadron slowly crawled up the shallows of the Patapsco River. Hebrus frequently got stuck in the river mud, having to be pulled off by her anchors.[29][30] At 6 a.m. on 13 September the ships reached Fort McHenry, halting around 2.75 miles (4.43 km) away.[31] The presence of the fort's batteries, alongside several hulks and booms, stopped the force from being able to access Baltimore's harbour.[32] The squadron began to bombard the fort, with most of the impact being done by the powerful bomb vessels rather than the frigates.[31] The British were out of range of the American guns, and received no return fire.[33] In the afternoon some of the bombs were sent in closer to the fort, but were forced back when they finally came in range of the Americans; Hebrus sent out her launch to reconnoitre the harbour to their front, where the 44-gun frigate USS Java was moored, but that was also forced to retire.[33][34] With the British Army assault from land having failed, after twenty-five hours of bombardment Cochrane ordered Gordon's squadron to stop firing, and they returned down the river.[35]

When the British Army made its way back to the fleet at North Point on 15 September, the Royal Navy vessels were brought into action to assist the wounded amongst them. Hebrus's half-deck was converted into a temporary hospital with cots erected for the casualties. Two or three men died on board in the following days.[36] On 17 September the fleet sailed to return to its former position off the Patuxent. Hebrus and Euryalus were diverted from this to escort the American ships captured at the Raid on Alexandria to Tangier Island. A midshipman on Hebrus recorded that as the ships left North Point the Americans raised a large ensign over the fort there and fired a ceremonial shot of resistance at the British ships.[37] After this Hebrus returned to the Patuxent, from where the majority of the ships split apart as some went with Cockburn to be refitted at Bermuda and some with Cochrane to Halifax as he prepared for operations at New Orleans. Hebrus was left off the Patuxent in a small squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcolm, guarding the troop ships and transports which had also been left behind. By 27 September they had moved to the Potomac River.[38]

In mid-October Hebrus was sent to Bermuda carrying the body of Captain Sir Peter Parker, who had been killed at the Battle of Caulk's Field; he was buried there on 14 October.[39] By December Hebrus was again serving under Cockburn, who sailed his force from the Chesapeake south towards Georgia.[40] Some time in the same month Hebrus sailed through a hurricane, in the aftermath of which the swell caused one man to fall overboard. Three boats were launched but as they searched for him a heavy fog rolled in and they failed despite his shouting.[41] On 12 December Hebrus was part of a group of ships that shared in the capture of the schooner Mary.[42]

In January 1815 Cockburn's force captured Cumberland Island.[43] At the subsequent Battle of Fort Peter on 13 January Hebrus was one of several ships to share in the capture of the merchant ship Countess of Harcourt, bark Maria Theresa, and schooner Cooler.[44] On 30 January Hebrus was off Edisto Island, where Palmer sent the ship's launch, tender, and two cutters to gather water. While there the watering party was spotted by the American militia stationed there, and they set out to push the British off the island. At the same time Lieutenant Lawrence Kearny sailed with three barges to cut off the retreat of the party. Hebrus saw Kearny as his barges approached and fired signal guns to the men on shore. The British quickly abandoned the watering site, leaving behind the launch in their rush.[45]

The cutters and tender sailed towards Hebrus but were cut off by Kearny who boarded and captured the tender. Hebrus began firing at the Americans and forced Kearny to stop his pursuit of the cutters, as a man near him was decapitated by Hebrus's fire. As Kearny returned to North Edisto the frigate sailed to cut him off, but he avoided Hebrus by diverting to South Edisto instead, taking the tender with him.[45] Thirty-six men were captured.[46]

Hebrus was one of several ships to share in the capture of the merchant brig Fortuna off Amelia Island on 17 February.[47] On 25 February Cockburn was informed by an American officer of the Treaty of Ghent, ending the war. Cockburn declined to officially suspend hostilities until news of the ratification of the treaty arrived, but no more offensive operations were undertaken by his ships.[48] Some time after this it was found that Parker, buried at Bermuda, had in fact wished to be buried in his family vault in St Margaret's, Westminster. As such Hebrus was tasked with taking his body to England, arriving at Portsmouth in May. She later moved to Sheerness, from where on 13 May the body was taken to Deptford before the funeral was held two days later.[49]

Hundred Days

[edit]In June Palmer was created a Companion of the Order of the Bath for his services.[50][7] Soon afterwards Hebrus was sent with a small expedition to Bourdeaux and the surrounding area, where it was expected that they would arm and organize French Royalists in the wake of the beginning of the Hundred Days.[23] In early July Hebrus joined with the 38-gun frigate HMS Pactolus, which had discovered Bourdeaux to be held by the Bonapartist General Bertrand Clauzel in a state of siege. Palmer persuaded the commander of Pactolus, Captain Frederick Aylmer (who was senior to him), to join him in attempting to take control of the Gironde estuary to ensure contact with Royalist forces on land.[51] On 11 July the ships sailed to enter the river, but as they closed with it five ships left the Gironde in a southerly direction, and the British abandoned their advance to chase them. Unbeknownst to them the British embargo on French trade had been lifted that morning, and having ascertained this the squadron reformed off the Gironde in the following night.[52]

Hebrus and Pactolus, alongside the 20-gun post ship HMS Falmouth, again attempted the Gironde on 13 July, with the frigates towing the accompanying transports behind them. They soon reached Royan which, while flying Bonapartist rather than Royalist flags, sent a boat out to them suggesting that if the British did not fire on them they would do the same. Despite the batteries along the river all being held by Bonapartist forces, the small squadron was not attacked until it reached Le Verdon-sur-Mer. There the gun batteries did open fire, but the British did not return fire in the hope that the impromptu peace could be continued, and no French fire hit the ships. After this they anchored off Bourdeaux and a line of communication was set up with Clauzel under a flag of truce. In the night the French abandoned the batteries at Verdon, and on 14 July the British landed a force to dismantle them and destroy the guns.[52]

Hebrus subsequently assisted in dismantling three French forts and destroyed seventy pieces of artillery.[53] While this was ongoing Palmer was entrusted with working with a French Royalist to persuade the remaining French batteries to change their allegiances. This they were very successful in, and by the end of the day all but one fort had raised the Royalist ensign.[54] On 16 July the ships sailed to Castillon; while there they received a dispatch from Clauzel announcing that the Hundred Days campaign had ended with an armistice. Palmer, who had previously negotiated with Clauzel, was sent back to Bordeaux. Together with a Royalist he secured Bordeaux as the troops loyal to Napoleon departed.[50]

Algiers

[edit]

Hebrus continued in service after the end of the wars, joining the Cork Station where the men filled their time on sailing excursions, playing cricket, and dancing at balls. On 8 July 1816 Palmer was given orders that Hebrus was to instead join the fleet under Admiral Lord Exmouth that was to bombard Algiers. With Hebrus's crew complement lower than usual for peacetime service, 100 men were taken from the 80-gun ship of the line HMS Tonnant to bolster her numbers. The ship then sailed to Plymouth Dockyard where over the next thirty-six hours she was fitted for active service.[55]

The fleet sailed for Gibraltar on 28 July with Hebrus towing a transport ship. Having arrived on 9 August at which point the fleet joined with a Dutch squadron, the force departed for Algiers on 14 August.[56] The ships arrived there on 26 August and at day-break the next morning sailed in close to the city, from where Pellew sent in letters of demands for the release of all Christian slaves. These went unanswered and after three hours the fleet organised itself into a line of battle off the mole.[50][57] The bombardment began at 2:45 p.m., with return fire coming from the Algerian gun batteries.[57]

Hebrus was kept in reserve, alongside the 36-gun frigate HMS Granicus and the smaller vessels, in the expectation that they would fill any gaps in the line of battle as they opened up. Hebrus sailed forward in an attempt to fill the first of these spaces soon after the firing had begun, but so much Algerian fire was aimed towards her that she was forced to anchor a little behind the line, to port of the 104-gun ship of the line HMS Queen Charlotte.[58][59] Granicus then passed Hebrus and filled the open position next to Queen Charlotte, and both frigates joined the cannonade, during which on several occasions Granicus sent a man on board Hebrus to complain that the latter's shot was hitting the former.[58][60][61] The bombardment continued until 9 p.m. when Pellew's ships sailed back out of range. Hebrus had four men killed and a further fifteen wounded in the engagement.[50][57]

Hebrus had taken twenty-two roundshot hits from the Algerian fire, and the crew spent the following night manning the pumps to remove the 1 foot 6 inches (0.46 m) of water that was entering the ship's hull each hour.[62] Hebrus was careened on 29 August to further inspect the damage, and then the following day was sent in close to shore to supervise the Christian ex-slaves being embarked in the transports, Algiers having agreed to abolish Christian slavery.[63] While this was being completed the crew were employed in weighting down the bodies that had been thrown from the ships during the bombardment and that were now floating back to the surface.[64] Hebrus was ordered back to Gibraltar on 4 September, before on 4 October the fleet returned to Plymouth.[65]

The service lives of pine-built ships were always noticeably shorter than those built of oak, and yellow pine ships are deemed by Gardiner to have had the "worst of all" lifespans.[6][5] After her return Hebrus was taken into dock where her timbers were discovered to be incredibly rotten, to the extent that they crumbled away when touched. She was paid off on 2 November and subsequently sold to Joshua Crystall for £2,110 on 3 April 1817.[6][5][66] In 1849 all living members of the crew were awarded the Naval General Service Medal with a clasp for the capture of Étoile.[67]

Prizes

[edit]| Vessels captured or destroyed for which Hebrus's crew received full or partial credit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Ship | Nationality | Type | Fate | Ref. |

| 27 March 1814 | Étoile | 44-gun frigate | Captured | [6] | |

| 12 December 1814 | Mary | Schooner | Captured | [42] | |

| 13 January 1815 | Countess of Harcourt | Ship | Captured | [44] | |

| Maria Theresa | Bark | Captured | |||

| Cooler | Schooner | Captured | |||

| 17 February 1815 | Fortuna | Brig | Captured | [47] | |

Citations

[edit]- ^ Winfield (2008), pp. 435, 437.

- ^ a b c d Winfield (2008), p. 435.

- ^ a b Gardiner (1999), p. 48.

- ^ a b Gardiner (2001), p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e Gardiner (1999), p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f Winfield (2008), p. 437.

- ^ a b Tracy (2006), p. 278.

- ^ Manning & Walker (1959), p. 226.

- ^ Marshall (1823), p. 228.

- ^ a b c d Clowes (1900), p. 546.

- ^ a b c Marshall (1827a), p. 215.

- ^ a b c d e f g Woodman (2001), p. 183.

- ^ Clowes (1900), pp. 545–546.

- ^ a b c d e Tracy (2006), p. 279.

- ^ a b Marshall (1827a), p. 216.

- ^ Whitehorne (1997), pp. 108–109.

- ^ Whitehorne (1997), p. 107.

- ^ Snow (2013), pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b c Whitehorne (1997), p. 117.

- ^ a b c d e Whitehorne (1997), p. 122.

- ^ Marshall (1830), p. 9.

- ^ Clowes (1901), p. 144.

- ^ a b c Marshall (1827a), p. 217.

- ^ Whitehorne (1997), p. 232.

- ^ Marshall (1830), p. 12.

- ^ Vogel (2013), pp. 201–202.

- ^ Vogel (2013), p. 202.

- ^ Snow (2013), p. 195.

- ^ Vogel (2013), p. 278.

- ^ a b Snow (2013), pp. 213–214.

- ^ Daughan (2011), p. 37.

- ^ a b Snow (2013), p. 215.

- ^ Snow (2013), p. 217–218.

- ^ Snow (2013), pp. 228–230.

- ^ Vogel (2013), p. 344.

- ^ Whitehorne (1997), p. 191.

- ^ Whitehorne (1997), pp. 195–196.

- ^ Dallas (1815), pp. 66–67.

- ^ Vogel (2013), p. 385.

- ^ Morris (1830), p. 383.

- ^ a b "No. 17363". The London Gazette. 26 May 1818.

- ^ Vogel (2013), pp. 385–386.

- ^ a b "No. 18015". The London Gazette. 3 April 1824.

- ^ a b Roosevelt (1906), pp. 158–159.

- ^ Alden (1961), p. 270.

- ^ a b "No. 18015". The London Gazette. 3 April 1824. p. 542.

- ^ Vogel (2013), p. 386.

- ^ Dallas (1815), p. 103.

- ^ a b c d Marshall (1827a), p. 218.

- ^ Marshall (1825), p. 950.

- ^ a b Marshall (1825), p. 951.

- ^ Marshall (1827a), pp. 217–218.

- ^ Marshall (1825), p. 952.

- ^ United Service Magazine (1831), p. 177.

- ^ United Service Magazine (1831), p. 178.

- ^ a b c Marshall (1823), pp. 225–226.

- ^ a b Marshall (1827b), p. 151.

- ^ Clowes (1901), p. 228.

- ^ United Service Magazine (1831), p. 181.

- ^ United Service Magazine (1831), p. 183.

- ^ United Service Magazine (1831), p. 185.

- ^ United Service Magazine (1831), p. 186.

- ^ United Service Magazine (1831), p. 187.

- ^ United Service Magazine (1831), p. 188.

- ^ United Service Magazine (1831), p. 189.

- ^ "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849.

References

[edit]- Alden, Carroll S. (1961). "Kearny, Lawrence". In Dumas Malone (ed.). Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. 5, part 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 7299519.

- Clowes, William Laird (1900). The Royal Navy, a History from the Earliest Times to the Present. Vol. 5. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 162571422.

- Clowes, William Laird (1901). The Royal Navy, a History from the Earliest Times to the Present. Vol. 6. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 634754813.

- Crawford, Michael J., ed. (2002). The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. Vol. 3. Washington D.C.: Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy. ISBN 0-16-051224-7.

- Dallas, Sir George (1815). A Biographical Memoir of the Late Sir Peter Parker, Baronet. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. OCLC 771791357.

- Daughan, George C. (2011). 1812: The Navy's War. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02046-1.

- Gardiner, Robert (1999). Warships of the Napoleonic Era. London: Chatham. ISBN 1-86176-117-1.

- Gardiner, Robert (2001). "Ships of the Royal Navy: The 18pdr Frigate". In Robert Gardiner (ed.). Fleet Battle and Blockade. London: Caxton Editions. ISBN 184067-363X.

- Manning, T. D.; Walker, C. F. (1959). British Warship Names. London: Putnam. OCLC 213798232.

- Marshall, John (1825). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 2, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 947–952.

- Marshall, John (1827a). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 215–218.

- Marshall, John (1823). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 209–228.

- Marshall, John (1830). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 4. London: Longman and company. pp. 8–20.

- Marshall, John (1827b). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 150–151.

- Morris, Robert (1830). "Affecting Incident at Sea". The Philadelphia Album. 4 (48): 383.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1906). The Naval War of 1812. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 174682499.

- Snow, Peter (2013). When Britain Burned the White House. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-1-84854-613-4.

- The United Service Journal and Naval and Military Magazine. London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley. 1831. OCLC 896748626.

- Tracy, Nicholas (2006). Who's Who in Nelson's Navy. London: Chatham. ISBN 978-1-86176-244-3.

- Vogel, Steve (2013). Through the Perilous Fight: Six Weeks that Saved the Nation. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6913-2.

- Woodman, Richard (2001). "The Final Frigate Actions". In Richard Woodman (ed.). The Victory of Seapower. London: Caxton Editions. ISBN 184067-3591.

- Whitehorne, Joseph A. (1997). The Battle for Baltimore 1814. Baltimore, Maryland: The Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America. ISBN 1-877853-23-2.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-78346-926-0.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch