Hananu Revolt

| Hananu Revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Syrian War | |||||||

Northwestern Syria, where the Hananu Revolt was based. The revolt was divided into four military zones: Jabal Qusayr, Jabal Sahyun, Jabal Zawiya and Jabal Harim | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| • Mandatory Syria • Army of the Levant | Rebel groups (′Isabat) of northern Syria Supported by: • • • | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

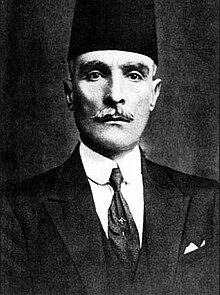

| | Ibrahim Hananu Najib Uwaid Umar al-Bitar Yusuf al-Sa'dun Mustafa al-Hajj Husayn Tahir al-Kayyali Abdullah ibn Umar Sha'ban Agha Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Ahmad bin Umar[1] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20,000 (2nd Division in Cilicia and Aleppo district) | ~5,000 irregulars | ||||||

| 1 A low-level insurgency continued until at least August 1926[2] | |||||||

The Hananu Revolt (also known as the Aleppo Revolt[3] or the Northern revolts) was an insurgency against French military forces in northern Syria, mainly concentrated in the western countryside of Aleppo, in 1920–1921. Support for the revolt was driven by opposition to the establishment of the French Mandate of Syria. Commonly named after its leading commander, Ibrahim Hananu, the revolt mainly consisted of four allied insurgencies in the areas of Jabal Harim, Jabal Qusayr, Jabal Zawiya and Jabal Sahyun. The rebels were led by rural leaders and mostly engaged in guerrilla attacks against French forces or the sabotage of key infrastructure.

The Hananu Revolt coincided with the Alawite Revolt in Syria's coastal mountains led by Saleh al-Ali, and both al-Ali and Hananu jointly referred to their revolts as part of the "general national movement of Western Aleppo". Despite early rebel victories, guerrilla operations ceased after the French occupation of Aleppo city in July 1920 and the dissolution of the Arab government in Damascus, the revolt's key backer. Hananu's forces renewed the revolt in November 1920 after securing substantial military aid from the Turkish forces of Mustafa Kemal, who were fighting the French for control of southern Anatolia.

At the revolt's peak in 1920, Hananu established a quasi-state in the region between Aleppo and the Mediterranean. The rebels were dealt major battlefield defeats in December 1920, and following agreements between the French and the Turks, Turkish military support for the rebels largely dissipated by the spring of 1921. French forces overran Hananu's last stronghold in Jabal Zawiya in July. Hananu was tried by the French Mandatory authorities and was ultimately acquitted. A low-level insurgency led by Yusuf al-Sa'dun persisted, with the last major military engagement with French forces occurring on 8 August 1926. The latter occurred during the countrywide Great Syrian Revolt, which began in the summer of 1925.

The collapse of the Hananu Revolt marked a significant turning point in Aleppo's political configurations. Whereas prior to the revolt, many in Aleppo's political elite were aligned with Turkish national politics, the betrayal that Aleppo's leaders felt at the withdrawal of Turkish support prompted most of them to embrace and pursue a shared destiny with the rest of Syria. Many were also influenced by Hananu's support for Syrian unity and strengthening ties with Damascus. In the aftermath of the Franco-Turkish accords, Aleppo's Anatolian hinterland, the major market for its goods and the supplier of its food and raw materials, was ceded to Turkey. This effectively severed commercial relations between Aleppo and Anatolia, harming the former's economy.

Background

[edit]In October 1918, Allied Forces and the Sharifian army wrested control of Syria from the Ottoman Empire. With British military support, the Hashemite leader of the Sharifian army, Emir Faisal, formed a rudimentary government in Damascus which extended its control to the northern inland Syrian cities of Homs, Hama and Aleppo. Meanwhile, France claimed special interests in Syria, per the Sykes-Picot agreement made with the British, and sought to establish a French Mandate over the region. The prospect of French rule was opposed by Syria's inhabitants.[4] French forces landed in the northern coastal city of Latakia in November 1918 and began to push inland through the coastal mountains, where they faced a revolt led by Saleh al-Ali, an Alawite feudal sheikh.[5]

Political and cultural sentiments in Aleppo

[edit]

At the time of the Arab Revolt and its aftermath, Aleppo's political elite was divided between those who embraced the Arab nationalist movement led by Faisal and those who sought political autonomy for Aleppo and its hinterland within the Ottoman state. A number of factors distinguished the attitudes of Aleppo's elite and populace from those of Damascus. For one, the economic well-being of Aleppo's inhabitants was dependent on open, commercial access to Aleppo's Anatolian hinterland, which was predominantly populated by Turks; southwestern Anatolia was the principal market for Aleppo's goods and the principal supplier of its food and raw materials.[6]

Furthermore, the political elite of Aleppo, which was considerably more ethnically and religiously diverse than the almost entirely Arab Muslim-populated Damascus, was culturally closer to Turkish-Ottoman society, and numerous members of Aleppo's elite were of Turkic, Kurdish and Circassian descent.[6] Because of these factors, many in Aleppo's political class did not support the 1916 Arab Revolt, and those who joined it felt that the revolt negatively exceeded their expectations because it ultimately ended Ottoman rule, thus breaking the bonds of Islamic unity and initiating the separation of Aleppo from its Anatolian hinterland.[7] There was also resentment in Aleppo, which under Ottoman rule had been the administrative center of the Aleppo Vilayet (Province of Aleppo) and was equal to Damascus in political stature, at the political dominance of Damascus under Faisal. While there were several Aleppines who held influential positions in Faisal's Damascus-based government, Faisal's leading political authorities in Aleppo were from Damascus or Iraq. However, French officials incorrectly believed that the rivalry between Aleppo and Damascus would make Aleppo's elite embrace French rule.[7] Instead, according to historian Phillip S. Khoury, Aleppo "vigorously resisted [French] occupation in order that its voice be heard in the new political climate."[7]

Several Aleppan dignitaries supported Emir Faisal and in late October 1918, following the Sharifian army's entry into Aleppo, a branch of the Arab Club was founded in the city.[8] The Arab Club's ideology was a mix of Arab nationalism and Aleppine regionalism.[9] It promoted the concept of Syrian national unity,[9] and served as a political support base for Emir Faisal.[8] Among the Arab Club's founders were Ibrahim Hananu, the president of Aleppo Vilayet's presidential council, Rashid al-Tali'a, governor of Aleppo Vilayet, Najib Bani Zadih, a wealthy Aleppine merchant, Abd al-Rahman al-Kayyali, an Aleppine physician and Shaykh Mas'ud al-Kawakibi, one of the city's leading Muslim scholars.[8][9]

Prelude and early rebel actions

[edit]

In November 1918, soldiers from Emir Faisal's army entered Antioch and were welcomed by the city's Arab inhabitants. In late November, French troops landed on the coast of the Gulf of Alexandretta and entered the city of Alexandretta, prompting anti-French uprisings in Antioch, al-Hamammat and Qirqkhan and the al-Amuq area. In December, French troops occupied Antioch and replaced the Arab flag on its governmental headquarters with the French flag. The revolts continued in the city's countryside, namely in the vicinity of Harbiya and al-Qusayr. The local uprisings spread from the Antioch region to Aleppo's countryside as far as the Euphrates.[10] The rebels consisted of small, disorganized ′iṣābāt (bands) and launched guerrilla-style attacks against French targets, but they also engaged in banditry and highway robberies.[11] An early attempt to coordinate the various rebel groups took place when one of the leaders of the Antiochian uprising and Alawite notable, Najib al-Arsuzi, developed contacts with rebel leaders from Jisr al-Shughur and other areas.[10]

British forces withdrew from Syria to Transjordan and Palestine in December 1919 as part of agreements with France over dividing control of the Ottomans' predominantly Arab territories[4] (later, in April 1920, France was given a mandate over Syria at the San Remo conference).[12] This left Faisal's rudimentary state vulnerable to French occupation.[4] The French demanded that Faisal rein in the ′iṣābāt,[13] which were not under Faisal's control.[14] Instead, Faisal opted to support and organize the northern rebels to prevent French advances from the coastal areas to the Syrian interior.[13] The Arab government entrusted two natives of northern Syria, Hananu,[13] a former Ottoman military instructor and a municipal official,[15] and Subhi Barakat, a notable from Alexandretta, with expanding and organizing the local uprisings into a full-blown revolt.[13]

Initially, Hananu logistically supported the guerrilla operations of Barakat against the French in the Antioch region. He later decided to organize a rebellion in Aleppo and its countryside.[16] Hananu was motivated to act by what he saw as the ineffectiveness of the Syrian National Congress, the legislative body of Faisal's state of which Hananu was a member, in preventing French rule.[5] He may also have been encouraged by Rashid al-Tali'a, the Arab government's district governor of Hama, who had been supporting Saleh al-Ali and the Alawite-dominated revolt he was leading against the French in the Syrian coastal mountains.[17] Meanwhile, the Syrian National Congress proclaimed the establishment of the Arab Kingdom of Syria in March 1920. France was wary that a popular nationalist movement emanating from Faisal's kingdom could spread to Lebanon and French territories in North Africa, and moved to put an end to Faisal's state.[4] Anti-French resistance manifested at local level as the Committees of National Defense, which began springing up in Aleppo and its hinterland. The committees were founded by members of the local elite, many of whom were sympathetic to Ottoman rule, but the committees quickly became fueled by populist agitation against French colonialism.[11]

Hananu gained the backing of Aleppo's Committee of National Defense, which consisted of numerous educated professionals, wealthy merchants and Muslim religious leaders.[18] The committee provided him with arms and funds, and helped promote his armed campaign among the city's Muslim scholars as well as put Hananu in touch with Ibrahim al-Shaghuri, head of the Arab Army's Second Division.[19] On orders from the Arab government in Damascus, Hananu formed an ′iṣābā in Aleppo consisting of seven men from his native Kafr Takharim, who he armed with hand-held bombs and rifles.[20] With al-Shaghuri's assistance, Hananu later expanded his ′iṣābā to forty fighters, known as mujahidin (fighters of a holy struggle), from Kafr Takharim and organized them into four equal-sized units.[19] According to historian Dalal Arsuzi-Elamir, the small size of each unit made them highly mobile and "able to inflict chaos on French troops".[20] Hananu used his family's farm in the regional administrative center of Harim as the headquarters of his branch of the Committee of National Defense.[15]

Revolt

[edit]First phase

[edit]Battle of Harim

[edit]Hananu's revolt coincided with Turkish revolts against the French military presence in the Anatolian cities of Urfa, Gaziantep and Mar'ash.[21] It also was related to Barakat's revolt in Antioch, which was captured and held by Arab guerrillas for a week starting on 13 March 1920. The French Air Force bombarded Antioch for 17 days until the rebels withdrew to Narlija.[20] On 18 April, taking advantage of the diversion of French forces to Gaziantep where a major battle between French and Turkish forces was taking place, Hananu decided to attack the French garrison at Harim.[21] With fifty of his irregulars, Hananu stormed the town. As word of his attack spread to nearby villages,[21] his forces subsequently swelled to 400.[17][21]

Hananu and Rashid al-Tali'a cooperated with Barakat in an attempt to unify northern Syria's rebel groups into a single resistance movement against the French, in allegiance with Faisal's government in Damascus.[22] Hananu also formed an alliance with the semi-nomadic Mawali tribesmen of the Aleppo region.[23] Following the battle at Harim, Hananu, with the assistance of Aleppo's Committee of National Defense, had collected up to 2,000 gold pounds in funds, and 1,700 rifles for the 680 men in his 'iṣābā,[18] who he and his aides trained.[9]

French occupation of Aleppo

[edit]

In April 1920, Hananu coordinated the shipment of Turkish arms to Saleh al-Ali's forces in their revolt against the French in the coastal mountains south of Latakia.[24] Faisal's government aided Hananu's movement financially and logistically via local Arab nationalist intermediaries. French General Henri Gouraud demanded that Faisal rein in the rebels of northern Syria and end their resistance to the French military advance.[25] Faisal continued to oppose French rule and his government launched a campaign to conscript soldiers from throughout the country in May as part of a last-ditch effort to defend Damascus against a French invasion, but the recruitment campaign was unsuccessful.[22] On 14 July, Gouraud issued an ultimatum to Faisal to demobilize his makeshift Arab Army and recognize France's mandate over Syria.[4] Later in mid-July, French forces broke Hananu's resistance lines in Jisr al-Shughur, capturing the town on their way to Aleppo.[25]

In late July, the French escalated their push into Syria's major inland cities. On 23 July, French troops led by General Fernand Goubeau,[26] commander of the Army of the Levant's Fourth Division,[27] captured Aleppo without resistance.[26] The lack of resistance was criticized by commander al-Sa'dun in his memoirs. In the aftermath of Aleppo's occupation, he organized 750 rebels to oust the French from the city, a plan that did not materialize.[28] The consequent flight of Aleppo's Arab nationalist leaders to the countryside and the French forces' military superiority managed to stymie a potential revolt in the city.[9] On 25 July, French forces captured Damascus a day after routing a small Arab Army contingent and armed volunteers led by Yusuf al-'Azma at the Battle of Maysalun.[4] Following the loss of Aleppo and Damascus, Barakat arranged a meeting of Antiochian rebel leaders in al-Qusayr, in which the attendants were divided between those who advocated either of the following: continuing the revolt, surrendering to the French or approaching the Turks for support. After the meeting, Barakat chose to defect to the French.[28] Afterward, al-Sa'dun and his fighters continued the revolt in Barakat's former area of operations.[29]

Hananu meanwhile left Aleppo, which had served as his urban base, and went to the village of Baruda to regroup and continue the revolt, rallying support around his leadership from the active ′iṣābāt in the western Aleppo countryside.[30] The revolt subsequently expanded to include four other ′iṣābāt, namely al-Sa'dun's ′iṣābā (over 400 rebels) in the Jabal Qusayr area near Antioch, Umar al-Bitar's ′iṣābā (150 rebels) in Jabal Sahyun in the mountains around al-Haffah northeast of Latakia, the ′iṣābā in Jabal Zawiya (200 rebels) under commander Mustafa al-Hajj Husayn and Najib Uwaid's ′iṣābā (250 fighters) around Kafr Takharim in Harim District.[30][31] Al-Sa'dun's area of operations were centered in Jabal Qusayr, but extended as far north as al-Amuq, as far south as Jisr al-Shughur, as far east as Darkush and far west as the Kesab area.[30]

An ′iṣābā from Jableh led by Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam also formed part of the revolt. The French military authorities considered al-Qassam's group, which relocated its headquarters to the Jabal Sahyun village of Zanqufa from Jableh in early 1920,[32] to be a part of al-Bitar's unit, but the two commanders operated in different sectors.[25] Al-Bitar's unit had been active in Jabal Sahyun since early 1919 soon after French forces landed in Latakia.[30] Al-Qassam left Syria to British-held Palestine sometime after the Battle of Maysalun to avoid capture by the French who issued a warrant for his arrest.[25]

Second phase

[edit]Alliance with Turkish forces

[edit]

With the Arab government in Damascus destroyed and Faisal exiled, Hananu's rebels sought to compensate for the consequent loss of aid from the Arab government. In the period following the Arab defeat, the rebels began appointing administrators in their territory who oversaw the institution of taxes to support the revolt, monthly salaries for the fighters and supply services for the 'iṣābā. They also sought military training by Turkish officers.[22]

Hananu and some of his aides traveled to Mar'ash to request support from the Anatolian insurgents and on 7 September, he signed a deal with them in which they recognized him as the representative of the Arab government of Syria and promised military aid.[30] In the course of that month, Hananu began receiving significant financial and military support, and military advisers, from the remnants of the Ottoman Second Army.[33] Despite the mutual suspicion between the nationalists in Aleppo and Turkey, who were leading their respective revolts, both sides agreed that they were confronting a common French enemy. In addition, the Turkish struggle to oust French forces from Anatolia was popularly supported by Syria's inhabitants, and in northern Syria in particular, there were widespread feelings of religious solidarity with the Turks.[34] In the second week of September, Saleh al-Ali announced that he was ready to coordinate with Hananu's rebels.[30]

The Turkish forces in Anatolia were led by Mustafa Kemal, who Hananu established contact with via intermediaries, chief of whom was Jamil Ibrahim Pasha. The latter, who was an Arabized Kurd, Ottoman World War veteran and absentee landlord from Aleppo, met Mustafa Kemal in Gaziantep in the late summer of 1920. During their meeting, an agreement was concluded to launch a propaganda campaign funded by the Turks against the French occupation. The campaign began in Aleppo in December 1920.[34]

Although an urban revolt in Aleppo did not take place in the aftermath of the city's occupation by French forces, many of Aleppo's inhabitants engaged in passive resistance against the French and clandestinely provided material aid to Hananu's rebels fighting in the rural areas west of the city.[9] In addition to the rebels' propaganda campaign, anti-French sentiment in Aleppo was growing due to socio-economic factors. These included the disruption of trade routes between Aleppo and its countryside, the hoarding and profiteering of flour and rising unemployment that was partially a result of an influx of Armenian refugees who had fled their villages in Turkey during the Armenian genocide.[34] The latter led to soaring prices for bread and subsequent food riots and famine in some of the city's neighborhoods. The French authorities also declared martial law, restricting travel and speech, further frustrating the inhabitants.

As a result of deteriorating conditions in the city attributed to French governance, the unpopular establishment of martial law, and the propaganda efforts of the rebels and their Turkish backers, many neighborhood leaders in Aleppo decided to recruit men to join Hananu's rebels, while many of the city's landowners and merchants donated funds to the rebel cause. The presence of 5,000 French Senegalese troops prevented an urban revolt that specifically targeted French forces, but in numerous incidents, Muslims from Aleppo's lower-income neighborhoods, such as Bab al-Nairab, violently assaulted members of the city's large Christian minority because they were viewed as being associated with French interests.[35]

Renewal of revolt

[edit]After the relative lull in fighting that followed the French occupation of Aleppo and Damascus, Hananu's forces resumed their guerrilla campaign in November 1920.[35] By then, Hananu's forces grew to about 5,000 irregulars.[33][36] Two months prior to the November offensive, the rebellions in the Antioch area and the Syrian coastal mountains had also resumed after temporarily tapering off in May 1920.[34] Armed action by Hananu's allies included an assault against the police station of Hammam, a village north of Harim, by 600 rebels in September. Gouraud stated in a report on 21 September that the rebels were in full control of Antakya, the road between the latter city and Aleppo and the Amanus Mountains.[28] Hananu's rebels sabotaged telegraph lines and railroads, captured and disarmed French troops, and disrupted French military movements into Aleppo city.[36] The repeated destruction of railroad and telegraph lines between Aleppo, Alexandretta and Beirut by Hananu and Saleh al-Ali's rebels placed the rebels in a position to take full control of northwestern Syria.[37]

By the end of November, the rebels gained control of the towns of Harim and Jisr al-Shughur and the villages of their districts. They then prepared for offensives to capture the towns and districts of Idlib and Maarrat al-Nu'man.[37] Other major scenes of fighting occurred at Isqat, Jisr al-Hadid, Kafr Takharim, Darkush, Talkalakh and the areas of al-Qusayr and Antioch.[30] At around the same time, Kurdish tribal forces countered the French at Viranşehir, east of Aleppo, and Bedouin forces commanded by ex-Ottoman officer Ramadan al-Shallash,[33] who declared his support for Hananu,[35] began guerrilla actions against French forces in the general vicinity of Raqqa.[33]

In the late winter of 1920, Hananu's rebels assaulted French forces in Idlib and according to the British consul in Aleppo, looted the town and killed some of its Christian inhabitants. Hananu's victory at Idlib and the arrival of Turkish military assistance led to a French withdrawal from Idlib.[33] Hananu's principal lieutenant commander in the Idlib operations was Tahir al-Kayyali,[38] who also served as president of the Arab Club of Aleppo and Aleppo's Committee of National Defense.[39] In early December, the French general of the 2nd Division in Aleppo, Henri-Félix de Lamothe, assembled a column at Hammam.[37] In mid-December, the French launched a counterattack on Idlib and burned down the city.[33] Afterward, General de Lamothe assembled a second column at Idlib.[37]

The French column from Hammam managed to capture Harim and Jisr al-Shughur from the rebels after a series of attacks and counterattacks between the two sides in late December. Hananu's rebels and Turkish irregulars launched a broad offensive to regain their positions in Harim, Jisr al-Shughur and Idlib, and according to Khoury, "a reversal seemed possible", as a result of the offensive. However, a French relief column arrived in the area and the French consolidated their hold over the three major towns. The French victories in December proved to be a decisive setback for Hananu's forces, who withdrew to Jabal Zawiya, a mountainous area south of Idlib. At Jabal Zawiya, Hananu and his commanders re-organized the rebels into more numerous, smaller units.[37]

In early 1921, using al-Shallash as an intermediary,[35] Hananu began receiving support from Emir Abdullah, the Hashemite emir of Transjordan and Faisal's brother.[40] Although the support from Emir Abdullah was relatively small in quantity, the French authorities feared it was part of a plot by Abdullah and his British allies to oust the French from Syria.[35] Hananu, meanwhile, was launching frequent hit-and-run operations against the French left flank in the area between Urfa and Antioch in an effort to support the Turks at the main battlefront in Gaziantep.[33]

Dwindling Turkish support

[edit]Hananu continued to receive arms and funds from Anatolia in early 1921, including a shipment in March consisting of 30 machine guns and 20 horse-loads of ammunition, which came after a larger weapons shipment via Jarabulus sometime in late February–early March.[33] The Turks and the French negotiated a treaty to end fighting in Cilicia, the southern Anatolian region north of Aleppo, in March.[41] That month, Hananu and Saleh al-Ali issued a joint letter to the League of Nations via the US and Spanish consuls in Aleppo in which the rebel leaders referred to themselves as commanders of the "general national movement in the region of Western Aleppo" and asserted that Syria sought to remain independent of France, and that the country was part of a broader Islamic community associated with the Ottoman state.[24]

Despite the treaty with France, Turkish forces in southern Anatolia continued to support Hananu's rebels with arms for a while longer to pressure the French further and gain more leverage in negotiations over territorial concessions.[41] At this point in the revolt, the rebels were in control of the villages of the Harim, Antioch, Jisr al-Shughur, Idlib and Maarrat al-Nu'man districts, but not the towns themselves. The French and Hananu entered into negotiations in the village of Kurin near Idlib in April, but they faltered. By order of the French Mandate's High Commissioner, Henri Gouraud, the French reinforced their military presence in the greater Aleppo region in April, and their columns defeated Hananu's rebels in a number of confrontations during this period.[5][41] By April, the French had over 20,000 troops in southern Anatolia and northern Syria, with over 5,000 troops in Aleppo, 4,500 in the Idlib district, 1,000 in Qatma and 5,000 in the Antioch region.[24] In May, French troops commanded by General Goubeau pursued Mawali and Sbaa Bedouin rebels after they launched several attacks against the highway between Homs and Hama. The Mawali surrendered after French aerial bombardments against their encampments in Qatara on 21 May.[42]

According to French intelligence reports, the Turks sent political agents to northern Syria to persuade the inhabitants to drop their armed resistance to the French and embrace French rule, which they claimed would benefit the population.[43] Sometime between April and May,[44] Hananu had Uwaid execute field commander Mustafa Asim Bey for his involvement in an attack against the mostly Christian town of al-Suqaylabiyah, in which many of its inhabitants were killed.[45] Asim Bey was a strongly pro-Ottoman, Arab officer with particularly close connections to the Anatolian insurgency.[38][46] Hananu believed that the Turks had instructed him to carry out the raids on al-Suqaylabiyah and other villages to tarnish the image of the rebels among the local inhabitants, as part of Turkey's agreements with France to stifle the revolt in northern Syria.[45] Asim's execution may have contributed to the rapid withdrawal of the rebels' Turkish military advisers who were upset with the execution.[44]

The arms flow from Anatolia ended in June, either due to a direct French diplomatic request or the diversion of arms and fighters to combat the Greek offensive against the Turks in western Anatolia. In any case, the stopping of weapons shipments had a significant impact on both the military aspect of the rebellion and morale, as Hananu and the revolt's backers in Aleppo felt abandoned by the Turks, who later concluded a final peace arrangement with France, known as the Treaty of Ankara, in October.[47] In need of funds, Hananu hired local bandits to extort money and supplies from Jabal Zawiya's inhabitants.[48] His main sources of weapons became limited to the towns of Maarrat al-Nu'man and Hama.[43] With the previous blows dealt to the rebels by French forces, the waning support for the revolt by the local inhabitants and the lack of weapons, Hananu's revolt largely dissipated during the spring of 1921,[41] although rebel operations against the French still continued at a reduced pace during this period.[43]

Suppression and aftermath

[edit]

Between the spring and early summer of 1921, the rebels experienced a series of defeats.[43] In July 1921, Hananu's stronghold in Jabal Zawiya was captured by French forces.[40] By this time, French forces proceeded to burn down villages where support for the rebels was high. A number of these villages' inhabitants were arrested or executed, prompting some rebels to ultimately surrender.[45] On 11 or 12 July, Hananu fled to British-held Transjordan, seeking refuge with nationalists from Syria,[43] to avoid arrest by the French authorities.[45][49] British intelligence officers arrested Hananu while he was visiting Jerusalem and extradited him to Syria in August.[43]

After six months of incarceration,[43] Hananu was subsequently put on trial on 15 March 1922,[49] with the charges against him including murder, organizing rebel bands, engaging in brigandage and the destruction of public property and infrastructure. He was defended by the Aleppine Christian attorney, Fathallah Saqqal.[43] In court, Hananu condemned the "illegal occupation of Syria" and argued that military operations were done under the aegis of Mustafa Kemal.[43] The trial became a rallying point of popular support for Hananu and a led to a significant degree of solidarity among Aleppo's urban elite who collectively supported Hananu's freedom. The trial concluded on 18 March, and Hananu was acquitted after the court decided that he was not a rebel, but rather a soldier who was legally mandated by the Ottoman authorities to engage in warfare against French forces.[49] According to Khoury, the "verdict would have been different ... had Hananu not become a legend in his own time" and if the Franco-Turkish War had not ended.[43]

Although Hananu's revolt was largely suppressed, a low-level insurgency involving small ′iṣābāt persisted in Aleppo's countryside.[41] Al-Sa'dun and Uwaid opted to continue the armed struggle, fleeing to the coastal mountains and from there to Turkey in December 1921. From the frontier area with Syria, they staged hit-and-run attacks against French forces. With 100 of his fighters, al-Sa'dun entered Jabal Zawiya in the summer of 1922 to punish those who defected from the rebels or residents who switched allegiance. On 26 August, al-Sa'dun's ′iṣābā assaulted a postal convoy in al-Darakiya, a village between Darkush and Antioch.[45] In 1923, rebel commander Aqil al-Saqati and ten of his fighters launched numerous attacks against the French, including an assault against a government building in al-Safira, southeast of Aleppo, and Jisr al-Hadid near Antakya.[2]

The insurgency in northwestern Syria continued and between December 1925 and August 1926, al-Sa'dun's fighters launched several attacks against French forces and military installments. These attacks coincided with the Great Syrian Revolt that started in the south of the country and spread to central and northern Syrian cities. Among the major engagements between al-Sa'dun's 'iṣābā and the French was at Tell Amar at the end of April 1926. The last major confrontation was at Jabal Qusayr on 8 August 1926.[45]

Rebel organization

[edit]The rebel groups were collectively known as ḥarakat al-′iṣābāt, and each individual ′iṣābā was composed of anywhere between 30 and 100 rebels known as mujahidin and were led by a ra'īs (commander), who was often a local notable or the head of a major clan.[50] Individual ′iṣābāt began forming in the countryside between Aleppo and Anatolia in 1919 to counter French advances, but Hananu gradually consolidated them into his network.[51]

The revolt was ultimately organized into four principal military zones, each headed by a ra'īs 'iṣābā native to the particular zone. The four zones were the following: Jabal Qusayr (Antioch area) headed by Sheikh Yusuf al-Sa'dun (headquarters in Babatorun), Jabal Harim headed by Najib Uwaid (headquarters in Kafr Takharim), Jabal Zawiya headed by Mustafa Haj Husayn and Jabal Sahyun (al-Haffah area) headed by Umar al-Bitar.[52] Hananu, the overall leader of the revolt, and the regional commanders discussed major military decisions, typically involving a particular guerrilla campaign or arms procurement, together. At times they also consulted with Ozdemir Bey, commander of Turkish irregulars fighting the French in Anatolia.[52]

At the height of the revolt, Hananu effectively created a quasi-independent state between Aleppo and the Mediterranean Sea.[17] Hananu's rebels first began administering captured territory in Armanaz, where the rebels coordinated with that town's municipality to impose taxes on landowners, livestock owners and farmers to fund their operations. From there, Hananu's administrative territory expanded to other towns and villages, including Kafr Takharim, and the district centers Harim, Jisr al-Shughur and Idlib. The municipal councils of these towns were not replaced, but repurposed to support the financial needs of the rebels and promote their social convictions. Kafr Takharim became the legislative center of rebel territory with a legislative committee in place to collect money and weapons from local sources, and a supreme revolutionary council to oversee judicial matters.[17]

Volunteers from the rural villages formed the bulk of the rebels' fighting force and during the course of the revolt, each village typically contained a 30-man reserve unit.[2] However, Hananu's forces also included volunteers from Aleppo city, former Ottoman conscripts,[35] Bedouin tribesmen (including some 1,500 Mawali fighters)[42] and Turkish officers who served as advisers.[35] The ′iṣābāt were rooted in the rural countryside, but also drew financial support from people in the cities.[53] While the rebels functioned as a traditional rural Syrian autonomous movement wary of centralized authority or foreign intervention into their affairs, they also sought to establish close ties with the Arab nationalist movement and, until the Arab Army's defeat at Maysalun, with representatives of the Arab government based in the cities.[52]

Besides military expertise, formal military language and style was important to rebel commanders as they sought to instill in their soldiers the "spirit, self-image and shape of an army", according to historian Nadine Méouchy.[54] During meetings of the rebel leadership, the mujahidin of the host leader assumed military formation by lining up along the road of the host village and saluting the visiting commanders.[54] The rebels referred to themselves as junūd al-thawra (sing. jundi), meaning "soldiers of revolt", which represented a more noble image than the term iṣābā, which was associated with banditry, and the term al-askar, which referred to the military and had negative connotations due to its association with conscription and repression. Each mujahid received a salary depending on his rank, with cavalrymen (fursan) or officers receiving higher pay than foot soldiers (mushāt).[55]

The rebels had multiple sources for arms, but did not possess heavy weaponry,[56] with the exception of two artillery pieces.[37] Sources for weapons included the Turkish forces in southern Anatolia, Bedouin tribes who either sold or smuggled Mauser rifles to the rebels that the Germans had distributed to the tribes during World War I, weapon stockpiles left behind by Ottoman troops fleeing Syria during the British-Arab offensive in 1918, and raids against French arms warehouses. The rebels' arsenal largely consisted of German Mauser rifles, revolvers, shotguns, and Turkish five-shooters, as well as sabres and daggers.[56] According to Khoury, the rebels also possessed twelve light machine guns.[37] Following the destruction of the Arab government in July 1920, the Turks became the main arms suppliers of the rebels. The rebels distinguished the Turkish armed movement in Anatolia from the Ottomans, who the rebels viewed negatively, by stressing the role of Turkish general Mustafa Kemal, who was viewed as the quintessential guerrilla leader in the struggle against French occupation.[50]

Tactics

[edit]Rebels

[edit]The chief operational goals of the ′iṣābāt were to inflict as much damage as they could on French forces and make clear their "determination to resist", according to Arsuzi.[57] The rebels utilized the familiar, mountainous terrain where they operated against the French forces, and typically launched guerrilla operations at night to avoid detection.[37][57] However, at times when the rebels could not avoid direct confrontation with French forces, they maintained fighting order similar to a regular army.[57]

French forces

[edit]Militarily, the French utilized large column formations against the rebels, a tactic which the French chief-of-staff of the Army of the Levant, General André-Gaston Prételat, found to be generally ineffective against small mobile rebel units. Instead, he believed the optimal way to defeat the rebels was to recruit local militias who would share the two main strengths of the rebels: knowledge of the terrain and high mobility.[41] However, the Syrian gendarmerie conscripted by the French military could not defeat the rebels because they were too small numerically, and not entirely reliable in battles against fellow locals.[28][41]

The French were more successful in persuading large landowners to cease support for the rebels and recruit local militias to protect highways from rebel attacks. The French also ultimately understood that in order to quell the revolt in Syria they needed to offer concessions in Anatolia and establish cooperation with the Turks, whose financial, military and moral support was critical to the rebels. When truces were reached with the Turks, the French redeployed large numbers of troops from the Anatolian front to suppress the rebels in Syria.[28][58]

Motivations for revolt

[edit]

Hananu's subordinate officers and rank-and-file fighters were all Sunni Muslims, but were ethnically heterogeneous. Hananu himself was a Kurd as were field commanders Najib Uwaid and Abdullah ibn Umar, while Umar al-Bitar was an Arab and field commander Sha'ban Agha was a Turk. The ′isabat led by al-Bitar and al-Qassam were dominated by Arabs.[59] The localized nature of the revolt reflected the rebels' sense of defending their homeland and community. Despite the eventual organization of the revolt and coordination between rebel commanders for major military decisions, most political decisions and military operations were local initiatives. As such, al-Sa'dun referred to the revolt in the plural as thawrat al-Shimal (Northern revolts) rather than the singular thawra, and referred to the leadership of the revolt as the plural quwwad al-thawra rather than qiyadat al-thawra, which refers to a central command.[60]

The rebels of the Hananu Revolt were motivated by three principal factors: defense of the homeland, which the rebels referred to as al-bilad or al-watan, defense of Islam in the face of conquest by an infidel enemy referred to as al-aduw al-kafir, in this case the French, and the defense of the rebels' traditional and sedentary way of life and the prevailing social order from foreign interference.[60] In the early phase of the revolt, Hananu and Barakat acted as representatives of Faisal's Arab government and continued to claim that they had the support of Faisal after the latter was ousted from Syria in July 1920.[57] Despite the collapse of the state they were ostensibly fighting under, the rebels resumed their struggle. In his memoirs, al-Sa'dun stated that the rebels engaged in jihad as an individual responsibility, instead of a duty delegated to them by a state. In his view, the individual rebel was required to behave virtuously in his personal life and with expertise and courage on the battlefield. Moreover, he had to strive to be a popular hero (batal sha'bi) close to his people, brave and pious.[60] Arsuzi-Elamir asserts that while religious terminology was used by the rebels, the rebels' "motivation was fundamentally nationalist" and that "religion does not seem to have played a more important role" than nationalist feeling.[57] Moreover, the Islamic solidarity between the Turks and the Syrians did not prevent the withdrawal of Turkish support for the revolt in Syria.[61]

According to historian Keith David Watenpaugh, the language used by Hananu and Saleh al-Ali in their address to the League of Nations "undermine" Arab and Turkish nationalist claims that their revolts represented part of the Arab or Turkish national awakenings. Hananu and al-Ali both referred to their revolts as part of a unified national resistance movement, but Watenpaugh states that the nation referred to was an Islamic community rather than the ethnic nationalism that steadily dominated Syrian and Turkish politics and society in the 20th century. Hananu and al-Ali also stressed modernist principles about individual rights, and according to Watenpaugh, Hananu did not view the concepts of modernity, Islam and the Ottoman state to be mutually exclusive. Hananu had opposed many Ottoman policies in the pre-World War I period, but was nonetheless wary of separatism as someone who formed part of the educated Ottoman middle class, while al-Ali sought a return to a "decentralized Ottoman polity dominated by Muslims in which the state would protect his hegemony as a landowning rural chieftain".[44] Hananu and the rebel commanders had a deep attachment to their place in society and viewed French rule as an assault on their status, ambitions and dignity.[44]

Legacy

[edit]

As a result of the Hananu and Alawite revolts, the French authorities discovered pacifying northern Syria was a more difficult task than pacification of the Damascus region.[62] Following the collapse of the Hananu Revolt, some political leaders in Aleppo continued to hope that the Turks would oust the French from northern Syria and unify Aleppo with its Anatolian hinterland,[62] but the withdrawal of Turkish support for the rebels in Syria, following agreements with France, caused a deterioration in Syrian-Turkish ties and left the rebels and nationalists of northern Syria feeling betrayed.[62] Disillusionment with Mustafa Kemal's policies regarding Syria made Turkey's remaining Syrian supporters realign their positions closer to Aleppo's Arab nationalists.[63] In the few years after the revolt, Aleppo's elite largely embraced the concept of a united Syrian struggle for independence from French rule. This shift also began a process of strengthening ties with the leaders of Damascus.[63]

Hananu's leadership of the revolt gained him wide popularity in Syria. Referring to Hananu, Khoury wrote "No name was more familiar to children growing up in Syria in the twenties and thirties; stories of his heroics were standard bedtime fare."[64] In Ba'athist historiography, Hananu became a hero of the Syrian Arab nationalist movement.[41] The Hananu Revolt was a turning point in Aleppo's relationship with the Arab nationalist movement. Under the influence of Hananu, his Arab Club, and other Aleppine leaders with similar politics, the Muslim elite of Aleppo gradually embraced Arab nationalism.[9] Hananu later became a founding member of the National Bloc in 1928, which according to Syrian historian Sami Moubayed, was "created out of the defeat of the armed revolts of the 1920s".[36] The National Bloc advocated diplomatic means to combat French rule and was the principal opposition movement against the French authorities until Syria's independence in 1946. Hananu served as the za'im (chief) of the movement until his death in 1935.[36][65]

In September 1920, Gouraud established the State of Aleppo, which consisted of the northern half of former Ottoman Syria, excluding the Tripoli district. The French authorities established a new bureaucratic administration in Aleppo led by four local, pro-French sympathizers and mostly staffed by their family members. After the revolt was stamped out, the French authorities arrested or exiled numerous Arab nationalist politicians in an attempt to end the nationalist alliance between Aleppo and Damascus. The authorities also began appointing former Ottoman administrators who were willing to cooperate with them to senior bureaucratic posts.[63] According to Khoury, "by 1922, the Aleppo bureaucracy had become more unwieldy and inefficient than it had been in the last years" of Ottoman rule.[66] Despite French attempts to completely exclude the nationalists from any administrative role, the overwhelming majority of Aleppo's population supported the nationalists.[66]

As a result of the Franco-Syrian War, Turkey annexed the southwestern Anatolian sanjaks (districts) that had been part of Aleppo Vilayet, such as Mar'ash following the Battle of Marash, Gaziantep ('Ayntab), Rumkale (Qal'at Rum) and Urfa (al-Ruha). These sanjaks became part of Turkey following the October 1921 treaty with France which ended the Franco-Turkish War. Aleppans opposed the Turkish annexation.[43] The Franco-Turkish treaty allowed for a resumption of commerce between Aleppo and the Alexandretta Sanjak, including Antioch, due to improved security conditions, but commerce between Aleppo and Anatolia largely ceased. Alexandretta was considered by Aleppans to be their port to the Mediterranean Sea and a crucial part of their socio-economic region. It remained part of Syria under French control, but was administered by a semi-autonomous government that was heavily influenced by Turkey. Aleppo's merchants and nationalist politicians feared this autonomy would ultimately lead to its annexation by Turkey and consequently precipitate an economic crisis in Aleppo;[67] Alexandretta was separated from Syria in 1938 and became part of Turkey in the following year when the Turkish Army marched into the region and annexed it.

References

[edit]- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008-08-29). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-09642-8.

- ^ a b c Arsuzi, ed. Sluglett and Weber 2010, p. 593.

- ^ Moubayed 2006, p. 604.

- ^ a b c d e f Neep 2012, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b c Fieldhouse 2006, p. 283.

- ^ a b Khoury 1987, p. 103.

- ^ a b c Khoury 1987, p. 104.

- ^ a b c Gelvin 1999, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e f g Khoury 1987, p. 106.

- ^ a b Arsuzi, ed. Sluglett and Weber 2010, pp. 586–587.

- ^ a b Neep 2012, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Arsuzi, Ed. Sluglett and Weber 2010, p. 582.

- ^ a b c d Arsuzi, ed. Sluglett and Weber 2010, p. 588.

- ^ Arsuzi, ed. Sluglett and Weber, p. 583.

- ^ a b Watenpaugh 2014, p. 175.

- ^ Gelvin 1999, p. 133.

- ^ a b c d Gelvin 1999, p. 134.

- ^ a b Khoury 1987, p. 105.

- ^ a b Gelvin 1999, pp. 133–134.

- ^ a b c Arsuzi-Elamir, ed. Sluglett and Weber 2010, p. 588.

- ^ a b c d Watenpaugh 2014, p. 176.

- ^ a b c Philipp and Schumann 2004, p. 279.

- ^ Philipp and Schumann 2004, p. 277.

- ^ a b c Watenpaugh 2014, p. 178.

- ^ a b c d Schleifer, S. Abdullah (1978). "The Life and Thought of 'Izz-id-Din al-Qassam". Islamic Quarterly. 20–24: 66–67.

- ^ a b Allawi 2014, p. 291.

- ^ Zeidner, Robert Farrer (2005). The Tricolor over the Taurus: The French in Cilicia and Vicinity, 1918–1922. Atatürk Supreme Council for Culture, Language and History. p. 218. ISBN 9789751617675.

- ^ a b c d e Arsuzi, ed. Sluglett and Weber 2010, p. 589.

- ^ Arsuzi, ed. Sluglett and Weber 2010, pp. 589–590.

- ^ a b c d e f g Arsuzi, ed. Sluglett and Weber 2010, p. 590.

- ^ Choueiri 1993, p. 19.

- ^ Schleifer, ed. Burke 1993, p. 169.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Watenpaugh 2014, p. 177.

- ^ a b c d Khoury 1987, p. 107.

- ^ a b c d e f g Khoury 1987, p. 108.

- ^ a b c d Moubayed 2006, p. 376.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Khoury 1987, p. 109.

- ^ a b Philipp and Schumann 2004, p. 261.

- ^ Gelvin 1999, p. 85.

- ^ a b Bidwell 2012, p. 174.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Neep 2012, p. 110.

- ^ a b Baxter 2013, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Khoury 1987, p. 110.

- ^ a b c d Watenpaugh 2014, p. 179.

- ^ a b c d e f Arsuzi-Elamir, ed. Sluglett and Weber 2010, p. 592.

- ^ Watenpaugh 2014, p. 115.

- ^ Watenpaugh 2014, p. 180.

- ^ Khoury 1987, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b c Watenpaugh 2014, pp. 180–181.

- ^ a b Méouchy, ed. Liebau 2010, p. 504.

- ^ Neep 2012, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Méouchy, ed. Liebau 2010, p. 510.

- ^ Philipp and Schumann 2004, p. 278.

- ^ a b Méouchy, ed. Liebau 2010, p. 512.

- ^ Méouchy, ed. Liebau 2010, pp. 511–512.

- ^ a b Méouchy, ed. Liebau 2010, p. 511.

- ^ a b c d e Arsuzi-Elamir, ed. Sluglett and Weber 2010, p. 594.

- ^ Arsuzi, ed. Sluglett and Weber 2010, pp. 591–592.

- ^ Philipp and Schumann 2004, pp. 260–261.

- ^ a b c Méouchy, ed. Liebau 2010, p. 514.

- ^ Arsuzi, ed. Sluglett and Weber 2010, p. 595.

- ^ a b c Khoury 1987, p. 111.

- ^ a b c Khoury 1987, p. 112.

- ^ Khoury 1987, p. 454.

- ^ Moubayed 2006, p. 377.

- ^ a b Khoury 1987, p. 114.

- ^ Khoury 1987, pp. 110–111.

Bibliography

[edit]- Allawi, Ali A. (2014). Faisal I of Iraq. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300127324.

- Arsuzi-Elamir, Dalal (2010). "The Uprisings in Antakya 1918–1926". In Peter Sluglett; Stefan Weber (eds.). Syria and Bilad Al-Sham Under Ottoman Rule: Essays in Honour of Abdul Karim Rafeq (PDF). Brill. ISBN 9789004181939. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-12-01.

- Baxter, Christopher (2013). Britain in Global Politics Volume 1: From Gladstone to Churchill, Volume 1. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137367822.

- Bidwell, Robin (2012). Dictionary of Modern Arab History. Routledge. ISBN 9781136162985.

- Choueiri, Youssef M. (1993). State and Society in Syria and Lebanon. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 9780859894104.

- Fieldhouse, D. K. (2006). Western Imperialism in the Middle East 1914–1958. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191536960.

- Gelvin, James L. (1999). Divided Loyalties: Nationalism and Mass Politics in Syria at the Close of Empire. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520919839.

- Khoury, Philip S. (1987). Syria and the French Mandate: The Politics of Arab Nationalism, 1920–1945. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400858392.

- Méouchy, Nadine (2010). "The Military and the Mujahidin in Action". In Leibau, Heike (ed.). The World in World Wars: Experiences, Perceptions and Perspectives from Africa and Asia. Brill. ISBN 9789004185456.

- Moubayed, Sami (2006). Steel and Silk. Cune Press. ISBN 1885942419.

- Neep, Daniel (2012). Occupying Syria Under the French Mandate: Insurgency, Space and State Formation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107000063.

- Philipp, Thomas; Schumann, Christoph, eds. (2004). From the Syrian Land to the States of Syria and Lebanon. Ergon in Kommission. ISBN 9783899133530.

- Rogan, Eugene L. (2012). The Arabs: A History. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465032488.

- Watenpaugh, Keith David (2014). Being Modern in the Middle East: Revolution, Nationalism, Colonialism, and the Arab Middle Class. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400866663.

External links

[edit]- Méouchy, Nadine (2014). "Chapitre 3 – Les temps et les territoires de la révolte du Nord (1919-1921)". In David, Jean-Claude; Boissière, Thierry (eds.). Alep et ses territoires (in French). Presses de l'Ifpo: Publications de l’Institut français du Proche-Orient. pp. 80–104. ISBN 9782351595275.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch