Heinrich Grüber

Heinrich Grüber | |

|---|---|

Bust on Heinrich-Grüber-Platz, Berlin | |

| Born | 24 June 1891 Stolberg, Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 29 November 1975 (aged 84) |

| Citizenship | German |

| Alma mater | Bonn, Berlin and Utrecht |

| Occupation(s) | theologian, pastor opposing Nazism, leader of relief organisations for the Nazi-persecuted and survivors |

| Years active | 1920–1940 (then jailed in Dachau) 1943-1975 |

| Spouse | Margarete Vits (1899-1986) |

| Children | 3 |

| Religion | Reformed |

| Church | Church of the old-Prussian Union (till 1948) Church in Berlin-Brandenburg |

| Ordained | 1920 |

Congregations served | Brackel, Kaulsdorf, St. Mary's Church, Berlin |

Offices held | EKD-plenipotentiary at the GDR cabinet (1949-1958) Provost of St. Mary's, Berlin (1945-1961) |

| Title | Dres. h.c. |

Heinrich Grüber (German: [ˈhaɪnʁɪç ˈɡʁyːbɐ] ; 24 June 1891 – 29 November 1975) was a Reformed theologian, pacifist and opponent of Nazism.

Life

[edit]| Righteous Among the Nations |

|---|

|

| By country |

Until 1933

[edit]Heinrich Grüber was born on 24 June 1891 in Stolberg in the Prussian Rhine Province (today part of North Rhine-Westphalia).[1] His parents were the teacher Ernst Grüber and Alwine Grüber, née Cleven from Gulpen,[1] living in the Protestant diaspora among an else prevailingly Catholic population.

After graduating in 1910 from the gymnasium in Eschweiler, Grüber studied philosophy, history and theology at the Rhenish Frederick William University in Bonn and the Frederick William University of Berlin between 1910 and 1913.[1] In Berlin he decided to become a pastor.[1] In 1913 and 1914 Grüber held a scholarship of the Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht, interrupted by his first state examination in theology in early 1914 and a first religious appointment in Beyenburg as vicar of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union,[1] a Protestant church combining congregations of Lutheran, Reformed and United Protestant alignment.

In 1915 Grüber was conscripted as a soldier and fought in World War I until 1918.[1] In early 1918 he started an education as a military chaplain and in mid-1918 he passed the second state examination in theology and was accepted into the preacher seminary (Domkandidatenstift) at Berlin's Supreme Parish and Collegiate Church.[1] He was tutored by court preacher Bruno Doehring.[1] In 1920 he was ordained as pastor in Berlin and took his first ministry in Brackel, Dortmund.[1] In June 1923 the French occupation forces prompted Grüber's expulsion from their occupied Ruhr area.[1] Exiled in Berlin, Grüber engaged for the Rhine-Ruhr Relief (Rhein-Ruhr-Hilfe) collecting donations for the poor impoverished by the Occupation of the Rhineland and the Ruhr area.[1] After his return in November 1923 he resumed his pastorate in Brackel, changing in 1925 to the Düsselthaler Anstalten, a diaconal youth welfare charity of the Inner Mission.[1]

Between 1926 and 1933 Grüber was head of the diaconal charity Stephanus-Stiftung Waldhof, a youth education institute (Jugendbildungsanstalt) in Templin.[1] In 1927 Grüber parallelly built up an ecclesiastical volunteer labour service for unemployed persons in the Uckermark.[1]

During the Nazi reign

[edit]In June 1933 he resigned from collaborating in the labour service after the Nazi government had merged the various volunteer labour services into the obligatory Reichsarbeitsdienst.[1] Thus provoking Nazi suspicion, Grüber was fired as head of Waldhof youth service in August the same year.[1] Already then Grüber joined the Nazi-opposing Emergency Covenant of Pastors (German: Pfarrernotbund).[2]

On 2 February 1934 the presbytery (Domkirchenkollegium) of the Berlin Supreme Parish and Collegiate Church appointed the Reformed Grüber as the new pastor of the Kaulsdorf congregation, since this church held the ius patronatus, giving its presbytery the advowson for the Jesus Church in Kaulsdorf.[3] The German Christian-dominated Kaulsdorf presbytery strictly rejected Grüber for being an opponent of their Faith Movement.[2] But the March of Brandenburg ecclesiastical provincial consistory (the competent bureaucracy within the old-Prussian Church) insisted on his appointment as decided by the presbytery of the Supreme Parish and Collegiate Church.[4] The office as old-Prussian pastor included the function as executive-in-chief of the Kaulsdorf presbytery. Thus conflicts were unavoidable. The German Christian presbyters of Kaulsdorf steadily denounced Grüber within the ecclesiastical bureaucracy for criticising Ludwig Müller, the then old-Prussian regional bishop (German: Landesbischof), and the Nazi party local group leader denounced him at the Gestapo, for criticising the Nazi sterilisation laws (see Nazi Eugenics) and for mercy and sympathy with the Jews.[5]

Once in office, Grüber built up a Confessing Church congregation at Jesus Church, convening the few congregants opposing the Nazi interference and adulteration of Protestantism, previously unable to organise as a group in Kaulsdorf. As the officially appointed pastor Grüber held the regular services in Jesus Church, preaching against the Cult of personality for Hitler, the severing armament of Germany and anti-Semitism.[6]

However, other events, such as collections of money for purposes of the Confessing Church, meetings of its adherents or elections of their brethren council, paralleling the German Christian-dominated presbytery, were forbidden to take place as events open for the public, but only card-carrying members of the opposing Confessing Church were allowed. Grüber carried the – due to their colour so-called – Red Card No. 4, issued on 22 December 1934 by the Kaulsdorf Confessing congregation.[7]

The information about Grüber's appointment spread among the adherents of the Confessing Church in neighbouring congregations comprising the competent deanery Berlin Land I, such as Ahrensfelde Village Church, Grace Church (Biesdorf), Blumberg, Fredersdorf bei Berlin, Friedrichsfelde Village Church, Heinersdorf Village Church, Tabor Church (Hohenschönhausen), Gospel Church (Karlshorst), Kleinschönebeck Village Church, Lichtenberg Village Church, Mahlsdorf Village Church, Marzahn Village Church, Neuenhagen bei Berlin, Petershagen bei Berlin, or Weißensee Village Church mostly without a local pastor supporting them. They started to travel for Sunday services to Jesus Church.[8] Grüber encouraged them to establish Confessing congregations of their own and attended e.g. the formal foundation of Friedrichsfelde Confessing congregation on 1 February 1935.[9]

Grüber presided over the Confessing synod of the deanery Berlin Land I, which constituted with Confessing synodals from the pertaining congregations on 3 March 1935 and paralleled the official deanery synod dominated by German Christians.[10] The Confessing congregants in Kaulsdorf's congregation became a great support for Grüber. He also provided for Confessing pastors, who would act in his place once he could not hold the service himself. In August 1935 his colleague Pastor Neumann from Köpenick preached instead of him, criticising the anti-Semitic policy of the German government, which earned him a denunciation by the Kaulsdorf presbytery.[6]

On the occasion of the Remilitarisation of the Rhineland in 1936 Adolf Hitler unconstitutionally and arbitrarily decreed a reëlection of the Nazi puppet Reichstag for 29 March, which was Palm Sunday the traditional day Protestant congregations would celebrate the confirmations of the confirmands, who had grown to ecclesiastical adulthood. The compromising Wilhelm Zoellner, leading the Protestant regional church bodies in Germany (1935–1937), regarded this an unfriendly act against Protestantism, but nevertheless obeyed and tried to delay the confirmations, asking a furlough for confirmands from the compulsory agricultural season labour of the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF), starting right next Monday. The DAF refused.

The second preliminary church executive (German: zweite Vorläufige Kirchenleitung) of the Confessing German Evangelical Church, paralleling the official bodies, was of the opinion that the confirmations were not to be delayed. Since fathers, being state officials and/or card-carrying Nazi partisans, were ordered to organise and implement the poll as election judges and with relatives travelling all around Germany to participate in their relatives' or godchildren's confirmations, the Nazis feared a low turnout in the election. This made the confirmations on the traditional date a political issue.

Thus only few pastors did not compromise in the end, but Grüber was one of the few (one out of 13 in Berlin, e.g.), who held the confirmation services as usual, even though the Nazi government had announced this would not be without consequences.[11] German Christian presbyters denounced Grüber again for his opposing attitudes at the March of Brandenburg provincial Consistory and the Gestapo.[12] The NSDAP local party leader (Ortsgruppenleiter) threatened Grüber to prompt his deportation to a concentration camp.[6] In 1936 Berlin's congregation of Dutch Reformed expatriates elected Grüber their pastor, which he remained until his arrest in 1940.[1][13][14]

The mainstream Nazi anti-Semitism considered the Jewry being a group of people bound by close, so-called blood (genetic) ties, to form a unit, which one could not join or secede from. The influence of Jews was declared to have detrimental impact on Germany, to rectify their discriminations and persecutions. To be spared from that, one had to prove one's affiliation with the group of the so-called Aryan race. Paradoxical was, that never genetic tests or outward allegedly racial features in one's physiognomy determined one's affiliation, although the Nazis palavered a lot about physiognomy, but only the records of religious affiliations of one's grandparents decided. However, while the grandparents were earlier still able to choose their religion, their grandchildren in the Nazi era were compulsorily categorised as Jews, if three or four grandparents were enrolled as members of a Jewish congregation.

This Nazi categorisation as Jews of course included mostly Jews of Jewish descent, but also many Gentiles of Jewish descent, such as Catholics, irreligionists, and Protestants, who happened to have had grandparents belonging – according to the records – to a Jewish congregation. While Jewish congregations in Germany tried – little as they were allowed – to help their persecuted members, the Protestant church bodies ignored their parishioners who were classified as Jews (according to the Nuremberg Laws), and the somewhat less persecuted Mischlinge of partially Jewish descent.

On 31 January 1936 the International Church Relief Commission for German Refugees constituted in London, but its actually envisaged German counterpart never materialised.[15] So Bishop George Bell gained his sister-in-law Laura Livingstone to run an office for the international relief commission in Berlin. The failure of the Confessing Church was evident, even though 70–80% of the Christian Germans of Jewish descent were Protestants.[16]

It was Grüber and some enthusiasts, who had started a new effort in 1936. They forced the Confessing Church's hand, which in 1938 supported the new organisation, named by the Gestapo Bureau Grüber, but after its official recognition Relief Centre for Protestant Non-Aryans.[17] Collaborators of the Bureau Grüber gave pastoral care to non-Aryans and helped them emigrate. Soon over 30 people worked in the Grüber Bureau, working closely with other organisations in Germany and abroad.

Since emigration opportunities for Jews were severely limited, even free nations forming traditional immigration destinations had shut their gates, pastoral care was a priority. The bureau also provided illegal aid to persecuted people, including false passports and medicine and food for concentration camp inmates.[14] Grüber's brother-in-law, Ernst Hellmut Vits, was head of the rayon manufacturer Vereinigte Glanzstoff-Fabriken and gave financial support to Grüber for the Bureau.[18]

In the night of 9 to 10 November 1938 the Nazi government organised the November Pogrom, often euphemised as Kristallnacht. The well-organised Nazi squads killed several hundreds, 1,200 Jewish Berliners were deported to Sachsenhausen concentration camp.[19] Many men went into hiding from arrest and also appeared at Grüber's home in the rectory of the Jesus Church. He organised their hiding in the cottages in the allotment clubs in his parish.[20]

The Nazis only released the arrested inmates, if they would immediately emigrate. Thus getting visa became the main target and problem of Grüber's Bureau. Grüber was allowed to travel several times to the Netherlands and Great Britain in order to persuade the authorities there to grant visa for the persecuted from Germany.[21] So Grüber found hardly time any more to serve his actual office as pastor in Kaulsdorf.[6]

From September 1939 the Bureau Grüber had to subordinate to the supervision by Adolf Eichmann.[22] Eichmann asked Grüber in a meeting about Jewish emigration why Grüber, not having any Jewish family and with no prospect for any thank, does help the Jews. Grüber answered because the Good Samaritan did so, and my Lord told me to do so.[23]

By autumn 1939 a new degree of persecution loomed. The Nazi authorities started to deport Jewish Austrians and Gentile Austrians of Jewish descent to German-occupied Poland. On 13 February 1940 the same fate hit 1,200 Jewish Germans and Gentile Germans of Jewish descent from the Stettin Region, who were deported to Lublin. Grüber learned about it by the Wehrmacht commander of Lublin and than protested at every higher ranking superior up to the then Prussian Minister-President Hermann Göring, who forbade further deportations from Prussia for the time being.[24] The Gestapo warned Grüber never to adopt party for the deported again.[25] The deported were not allowed to return.

On 22–23 October, 6,500 Jewish Germans and Gentile Germans of Jewish descent from Baden and the Palatinate were deported to Gurs, German-occupied France. Now Grüber got himself a passport, with the help of Dietrich Bonhoeffer's brother-in-law Hans von Dohnanyi from the Abwehr, to visit the deported in the Gurs (concentration camp). But before he left the Gestapo arrested Grüber on 19 December and deported him two days later to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, and in September 1941 to Dachau concentration camp, becoming the inmate with the No. 27832.[24][26] His deputy Werner Sylten had to devolve the Bureau.

For 18 December 1942 Grüber's wife Margarete, still living in the rectory of the Kaulsdorf congregation, managed to get a visitor's permit to speak him, accompanied by their elder son Hans-Rolf, for 30 minutes in Dachau, arguing that he, being the husband and thus according to the garbled Nazi ideas of family values the decision-taking party in the family, would have to decide about important financial matters, about which he would have to instruct the remaining eldest, though minor, male family member.[27] Grüber survived Dachau and built up good relations with many other inmates, among them also communists. He was eventually released due to international efforts and multiple interventions by Vits to his family in Kaulsdorf on 23 June 1943,[28] after signing not to help the persecuted any more. He could not resume his rescue work.

Grüber then resumed his office as pastor of Kaulsdorf and the Confessing Church in the Berlin Land I deanery. He reported in the Confessing congregations of the deanery about the truth in a concentration camp, such as Dachau and Sachsenhausen.[29] On 22 April 1945 at the invasion of the Red Army into the Kaulsdorf neighbourhood Grüber gathered some undaunted Kaulsdorfers to follow him with white flags marching in direction of the Soviet soldiers in order to avoid further bloodshed.[6] The Soviet forces appointed him headman of the Kaulsdorf neighbourhood.[1]

After World War II

[edit]In the massive rapes of girls and women by the Soviet soldiers in the following weeks and months Grüber organised to hide girls and women.[30] In 1945 Kaulsdorf turned out to be part of the Soviet Eastern Sector of Berlin.

Grüber reopened his Bureau, now serving survivors, returning from the concentration camps, in Berlin's Bethany Hospital in the American Sector of Berlin. Otto Dibelius, who had assumed the post-war leadership of the old-Prussian March of Brandenburg ecclesiastical province for the time being, appointed Grüber as one of the Nazi opposing pastors for the new leading bodies to be established.

On 18 May 1945 Berlin's provisional city council, newly installed by the Soviet occupational power, had appointed Grüber as advisor for ecclesiastical affairs. This earned him a bilingual Russian-German certificate, issued on 21 May, to spare him from the usual robbery of bikes by Soviet soldiers, so that he could move at all in the city, with all the transportation system having collapsed, and an exemption from the curfew valid for Germans, issued on 9 July.[31] On 15 July 1945 Dibelius appointed Grüber as Provost of St. Mary's and St. Nicholas' Church in Berlin and invested him on 8 August in a ceremony in St. Mary's Church, only partially cleared from the debris.[32] Thus his time as pastor in Kaulsdorf ended.

In 1946 Grüber prepared and became in 1947 one of the co-founders of the Union of Persecutees of the Nazi Regime in the boards of which he collaborated until 1948.[1] Grüber's organisation for the relief of the survivors, today a diaconal charity named Evangelical Relief Centre for the formerly Racially Persecuted, found later new premises in West Berlin's locality of Zehlendorf, so the Grübers had moved there in 1949.

With his contacts from Dachau to communists, in 1949 the Evangelical Church in Germany, the umbrella of the regional churches, appointed Grüber as its plenipotentiary with the Council of Ministers of the GDR where he could – at least to some extent – soften many of the ever-increasing anti-clerical measurements of the communist regime to be established in the East, until the communist rulers of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) finally dropped him in May 1958.[1][33]

In 1959 the Evangelical Relief Centre for the formerly Racially Persecuted opened a modern home for the elderly formerly Persecuted, named Heinrich-Grüber-Haus,[1] replacing an older home for the same purpose of the same name. In June 1961 Grüber testified during the Eichmann Trial in Jerusalem,[1] being the only German non-Jewish witness of the prosecution. From 1964 on East Germany denied Grüber an entry into East Berlin or the GDR.[1]

Heinrich Grüber died on 29 November 1975 in West Berlin.[14]

Family

[edit]On 27 May 1920 Grüber and Margarete Vits (1899-1986) married. They had three children, the physician Ingeborg Grüber (1921-2000), the pastor Ernst-Hartmut Grüber (1924-1997), and the jurist Hans-Rolf Grüber (1925-2015).

Honours and awards

[edit]

- 1948, 16 July: first honorary degree of the Theological department of the Humboldt University

- 1950, about: Heinrich-Grüber-Haus for the elderly formerly persecuted

- 1956, 12 May: first honorary degree of the der Comenius department of the Prague University

- 1956, 24 June: Otto Dibelius renamed the community hall of Mitte's St. Mary's congregation on Bischofstr. 6-8 in Propst-Grüber-Haus,[34] removed by 1968.[35]

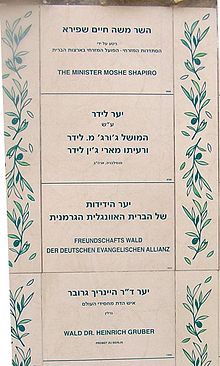

- 1961, 18 October: Wald Dr. Heinrich Grüber / יער ד"ר היינריך גרובר dedicated within the Jerusalem Forest

- 1962: honorary degree of the Theological department of the Lutheran Wagner College on Staten Island, New York City

- 1962, 28 July: honorary degree of the Theological Brethren Church Faculty in Chicago

- 1962, 10 October: honorary degree of Human Letters by the Hebrew Union College, New York City

- 1963: Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany 1st class

- 1964, 28 July: Grüber recognised as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem[36]

- 1966, 21 June: Commander of Order of Orange-Nassau, decorated by Juliana of the Netherlands

- 1965, 9 December: Carl von Ossietzky Medal awarded by the International League for Human Rights (Berlin)

- 1966: honorary president of the German-Israeli Society

- 1967, January: Albert Schweitzer Medal by the 'Nederlands Albert Schweitzer Fonds' in Amsterdam

- 1968: Silver Youth Aliyah Medal by the Jewish Agency for Israel

- 1970: Luther Medal of the Evangelical Church in Berlin-Brandenburg

- 1970, 8 May: honorary citizenship of West Berlin

- 1971: Golden Cross of the Diakonisches Werk

- 1971, 31 March: decoration as 'Defender of Freedom', by George M. Seignious, Commandant of the American Sector of Berlin[37]

- 1975: honorary grave on the 'Cemetery II' of the Protestant Congregation of the Supreme Parish and Collegiate Church on Müllerstraße, Wedding (Berlin).

- 1991, 24 June: renaming of 'Hönower Straße' into Heinrich-Grüber-Straße in Kaulsdorf, Berlin[38]

- 1997, 22 December: inauguration of a memorial plaque for Grüber on the outside wall of Jesus Church, Kaulsdorf[39]

- 2007: 'Hauptschule Liester' school in Stolberg (Rhineland) renamed as Propst-Grüber-Schule

- 2008, 21 May: square in Kaulsdorf renamed as Heinrich-Grüber-Platz.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Cf. Prussian Privy State Archives (GStA PK), VI. HA, Nl Grüber, H. Einleitung (introduction) Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 5 November 2015.

- ^ a b Heinrich Grüber. Sein Dienst am Menschen, Peter Mehnert for Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte and Bezirksamt Hellersdorf (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1988, p. 6. No ISBN

- ^ "Deed of appointment of Heinrich Grüber", issued by the Domkirchenkollegium on 7 February 1934, published in: Heinrich Grüber. Sein Dienst am Menschen, Peter Mehnert on behalf of the Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte and Bezirksamt Hellersdorf (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1988, p. 6. No ISBN

- ^ Die Kirchen und das Dritte Reich: 3 vols., Klaus Scholder and Gerhard Besier, Frankfurt am Main et al.: Propyläen et al., 1977–, vol. 3: Gerhard Besier 'Spaltungen und Abwehrkämpfe 1934–1937' (2001), footnote 378 on p. 1152. ISBN 3-549-07149-3.

- ^ Die Kirchen und das Dritte Reich: 3 vols., Klaus Scholder and Gerhard Besier, Frankfurt am Main et al.: Propyläen et al., 1977–2001, vol. 3: Gerhard Besier 'Spaltungen und Abwehrkämpfe 1934–1937' (2001), p. 865 and footnote 379 on p. 1152. ISBN 3-549-07149-3.

- ^ a b c d e Dieter Winkler, "Heinrich Grüber und die Kaulsdorfer", in: Heinrich Grüber und die Folgen: Beiträge des Symposiums am 25. Juni 1991 in der Jesus-Kirche zu Berlin-Kaulsdorf, Eva Voßberg (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1992, (=Hellersdorfer Heimathefte; No. 1), pp. 30–32, here p. 31. No ISBN

- ^ Cf. "Red Card of Heinrich Grüber", published in Heinrich Grüber. Sein Dienst am Menschen, Peter Mehnert for Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte and Bezirksamt Hellersdorf (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1988, p. 9. No ISBN

- ^ Gundula Tietsch, "Berlin-Friedrichsfelde", in: Kirchenkampf in Berlin 1932–1945: 42 Stadtgeschichten, Olaf Kühl-Freudenstein, Peter Noss, and Claus Wagener (eds.), Berlin: Institut Kirche und Judentum, 1999, (=Studien zu Kirche und Judentum; vol. 18), pp. 340–352, here p. 342. ISBN 3-923095-61-9.

- ^ Gundula Tietsch, "Berlin-Friedrichsfelde", in: Kirchenkampf in Berlin 1932–1945: 42 Stadtgeschichten, Olaf Kühl-Freudenstein, Peter Noss, and Claus Wagener (eds.), Berlin: Institut Kirche und Judentum, 1999, (=Studien zu Kirche und Judentum; vol. 18), pp. 340–352, here p. 341. ISBN 3-923095-61-9.

- ^ Gundula Tietsch, "Berlin-Friedrichsfelde", in: Kirchenkampf in Berlin 1932–1945: 42 Stadtgeschichten, Olaf Kühl-Freudenstein, Peter Noss, and Claus Wagener (eds.), Berlin: Institut Kirche und Judentum, 1999, (=Studien zu Kirche und Judentum; vol. 18), pp. 340–352, here p. 345. ISBN 3-923095-61-9.

- ^ Die Kirchen und das Dritte Reich: 3 vols., Klaus Scholder and Gerhard Besier, Frankfurt am Main et al.: Propyläen et al., 1977–, vol. 3: Gerhard Besier 'Spaltungen und Abwehrkämpfe 1934–1937' (2001), p. 438 and footnote 58 on p. 1035. ISBN 3-549-07149-3.

- ^ Dieter Winkler, "Heinrich Grüber und die Kaulsdorfer", in: Heinrich Grüber und die Folgen: Beiträge des Symposiums am 25. Juni 1991 in der Jesus-Kirche zu Berlin-Kaulsdorf, Eva Voßberg (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1992, (=Hellersdorfer Heimathefte; No. 1), pp. 30–32, here p. 30. No ISBN

- ^ Heinrich Grüber. Sein Dienst am Menschen, Peter Mehnert for Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte and Bezirksamt Hellersdorf (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1988, p. 2. No ISBN

- ^ a b c Heinrich Grüber – Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand.

- ^ Hartmut Ludwig, "Das ›Büro Pfarrer Grüber‹ 1938–1940", in: ›Büro Pfarrer Grüber‹ Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte. Geschichte und Wirken heute, Walter Sylten, Joachim-Dieter Schwäbl and Michael Kreutzer on behalf of the Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte (ed.; Evangelical Relief Centre for the formerly Racially Persecuted), Berlin: Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte, 1988, pp. 1–23, here p. 7. No ISBN.

- ^ Ursula Büttner, "Von der Kirche verlassen: Die deutschen Protestanten und die Verfolgung der Juden und Christen jüdischer Herkunft im »Dritten Reich«", in: Die verlassenen Kinder der Kirche: Der Umgang mit Christen jüdischer Herkunft im »Dritten Reich«, Ursula Büttner and Martin Greschat (eds.), Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1998, pp. 15–69, here footnote 9 on pp. 20seq. (ISBN 3-525-01620-4) and Hartmut Ludwig, "Das ›Büro Pfarrer Grüber‹ 1938–1940", in: ›Büro Pfarrer Grüber‹ Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte. Geschichte und Wirken heute, Walter Sylten, Joachim-Dieter Schwäbl and Michael Kreutzer on behalf of the Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte (ed.; Evangelical Relief Centre for the formerly Racially Persecuted), Berlin: Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte, 1988, pp. 1–23, here p. 8. No ISBN.

- ^ The name was in German: Hilfsstelle für evangelische Nichtarier. Cf. the Bescheinigung (certification) of the Reichsstelle für das Auswanderungswesen (29 December 1938), published in Heinrich Grüber. Sein Dienst am Menschen, Peter Mehnert on behalf or the Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte and Bezirksamt Hellersdorf (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1988, p. 11. No ISBN.

- ^ Homberg 2008, p. 9, 101ff.

- ^ Claus Wagener, "Nationalsozialistische Kirchenpolitik und protestantische Kirchen nach 1933", in: Kirchenkampf in Berlin 1932–1945: 42 Stadtgeschichten, Olaf Kühl-Freudenstein, Peter Noss, and Claus Wagener (eds.), Berlin: Institut Kirche und Judentum, 1999, (=Studien zu Kirche und Judentum; vol. 18), pp. 76–96, here p. 87. ISBN 3-923095-61-9.

- ^ Hartmut Ludwig, "Das ›Büro Pfarrer Grüber‹ 1938–1940", in: ›Büro Pfarrer Grüber‹ Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte. Geschichte und Wirken heute, Walter Sylten, Joachim-Dieter Schwäbl and Michael Kreutzer on behalf of the Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte (ed.; Evangelical Relief Centre for the formerly Racially Persecuted), Berlin: Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte, 1988, pp. 1–23, here p. 2. No ISBN.

- ^ Heinrich Grüber. Sein Dienst am Menschen, Peter Mehnert for Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte and Bezirksamt Hellersdorf (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1988, p. 12. No ISBN

- ^ Hartmut Ludwig, "Das ›Büro Pfarrer Grüber‹ 1938–1940", In: ›Büro Pfarrer Grüber‹ Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte. Geschichte und Wirken heute, Walter Sylten, Joachim-Dieter Schwäbl and Michael Kreutzer on behalf of the Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte (ed.; Evangelical Relief Centre for the formerly Racially Persecuted), Berlin: Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte, 1988, pp. 1–23, here p. 15. No ISBN.

- ^ Analogously after Grüber's testimony in the Eichmann Trial, on 14 May 1961, here after Heinrich Grüber. Sein Dienst am Menschen, Peter Mehnert for Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte and Bezirksamt Hellersdorf (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1988, p. 26. No ISBN

- ^ a b Hartmut Ludwig, "Das ›Büro Pfarrer Grüber‹ 1938–1940", in: ›Büro Pfarrer Grüber‹ Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte. Geschichte und Wirken heute, Walter Sylten, Joachim-Dieter Schwäbl and Michael Kreutzer on behalf of the Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte (ed.; Evangelical Relief Centre for the formerly Racially Persecuted), Berlin: Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte, 1988, pp. 1–23, here p. 21. No ISBN.

- ^ Israel Gutman, Daniel Fraenkel, Sara Bender, and Jacob Borut (eds.), Lexikon der Gerechten unter den Völkern: Deutsche und Österreicher [Rashût ha-Zîkkarôn la-Sho'a we-la-Gvûrah (רשות הזכרון לשואה ולגבורה), Jerusalem: Yad VaShem; German translation], Uwe Hager (trl.), Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2005, article: Heinrich Grüber, pp. 128seqq., here p. 130. ISBN 3-89244-900-7.

- ^ Grueber FAMILY – Yad Vashem.

- ^ Heinrich Grüber. Sein Dienst am Menschen, Peter Mehnert for Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte and Bezirksamt Hellersdorf (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1988, p. 15. No ISBN

- ^ Schnöring 1981, pp. 101ff.

- ^ Gundula Tietsch, "Berlin-Friedrichsfelde", in: Kirchenkampf in Berlin 1932–1945: 42 Stadtgeschichten, Olaf Kühl-Freudenstein, Peter Noss, and Claus Wagener (eds.), Berlin: Institut Kirche und Judentum, 1999, (=Studien zu Kirche und Judentum; vol. 18), pp. 350–352, here p. 351. ISBN 3-923095-61-9.

- ^ Dieter Winkler, "Heinrich Grüber und die Kaulsdorfer", in: Heinrich Grüber und die Folgen: Beiträge des Symposiums am 25. Juni 1991 in der Jesus-Kirche zu Berlin-Kaulsdorf, Eva Voßberg (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1992, (=Hellersdorfer Heimathefte; No. 1), pp. 30–32, here p. 32. No ISBN

- ^ Heinrich Grüber. Sein Dienst am Menschen, Peter Mehnert for Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte and Bezirksamt Hellersdorf (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1988, p. 16. No ISBN

- ^ Heinrich Grüber. Sein Dienst am Menschen, Peter Mehnert for Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte and Bezirksamt Hellersdorf (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1988, p. 18. No ISBN

- ^ Heinrich Grüber. Sein Dienst am Menschen, Peter Mehnert for Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte and Bezirksamt Hellersdorf (ed.), Berlin: Bezirkschronik Berlin-Hellersdorf, 1988, p. 23. No ISBN

- ^ "Probst Grüber: Im Lande meines Elends", Der Spiegel, 13 September, Titelgeschichte, hier S. 19, no. 26, pp. 18–25, 1956, archived from the original on 11 May 2016, retrieved 13 September 2016

- ^ Michael Kreutzer, Joachim-Dieter Schwäbl, Walter Sylten, „Mahnung und Verpflichtung“, in: ›Büro Pfarrer Grüber‹ Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte. Geschichte und Wirken heute, Walter Sylten, Joachim-Dieter Schwäbl, Michael Kreutzer (eds.) on behalf of Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte, Berlin: Evangelische Hilfsstelle für ehemals Rasseverfolgte, 1988, pp. 24–29, here p. 27. No ISBN.

- ^ Israel Gutman et al. (ed.), Lexikon der Gerechten unter den Völkern: Deutsche und Österreicher, Göttingen: Wallstein, 2005, p. 130.

- ^ Cf. NN., "Heinrich Grueber Receives Defender of Freedom Award" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, in: The Berlin Observer, vol. 27, No. 13, 2 April 1971, p. 1.

- ^ „Heinrich-Grüber-Straße“ Archived 10 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine, in: Straßennamenlexikon des Luisenstädtischen Bildungsvereins (bei Kaupert)

- ^ "Gedenktafel für Heinrich Grüber in Kaulsdorf schwer beschädigt". 18 December 2016. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

Sources

[edit] Media related to Heinrich Grüber at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Heinrich Grüber at Wikimedia Commons

- "Grueber FAMILY". The Righteous Among The Nations. Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- "Heinrich Grüber" (in German). Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand. Archived from the original on 17 December 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- Homberg, Frank Friedhelm (2008). Retterwiderstand in Wuppertal während des Nationalsozialismus (in German). Dissertation for Dusseldorf University. Düsseldorf. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schnöring, Kurt (1981). Auschwitz begann in Wuppertal (in German). Wuppertal: Peter Hammer Verlag. ISBN 3-87294-174-7.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch