Henry Ossian Flipper

Henry Ossian Flipper | |

|---|---|

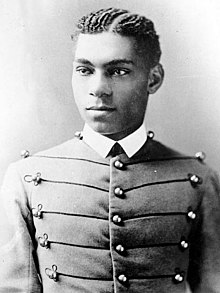

Cadet Henry O. Flipper USMA Class of 1877 | |

| Born | March 21, 1856 Thomasville, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | April 26, 1940 (aged 84) Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1877–1882 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 10th Cavalry Regiment |

| Battles / wars | Indian Wars |

| Other work | Civil engineer |

Henry Ossian Flipper (March 21, 1856 – April 26, 1940) was an American soldier, engineer, former slave and in 1877, the first African American to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point, earning a commission as a second lieutenant in the United States Army. He was also an author who wrote about scientific topics and his life experiences.

After his commissioning, he was assigned to one of the all-black regiments in the U.S. Army, which were historically led by white officers. Assigned to 'A' Troop under the command of Captain Nicholas M. Nolan, he became the first nonwhite officer to lead buffalo soldiers of the 10th Cavalry. Flipper served with competency and distinction during the Apache Wars and the Victorio Campaign, but was haunted by rumors alleging improprieties. Eventually, he was court-martialed and dismissed from the U.S. Army.

After losing his commission in the Army, Flipper worked throughout Mexico and Latin America as an assistant to the Secretary of the Interior. He retired to Atlanta in 1931 and died of natural causes in 1940.

In 1976, his descendants applied to the U.S. military for a review of Flipper's court-martial and dismissal. A review found the conviction and punishment were "unduly harsh and unjust" and ordered Flipper's dismissal be changed to a good conduct discharge. Shortly afterwards, an application for pardon was filed with the Secretary of the Army, which was forwarded to the Department of Justice. Eventually, President Bill Clinton posthumously pardoned Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper on February 19, 1999, 118 years after his conviction.

Early life and education

[edit]Flipper was born into slavery in Thomasville, Georgia, the eldest of five brothers including Joseph Simeon.[1] His mother, Isabelle Flipper, and his father, Festus Flipper, a shoemaker and carriage-trimmer, were enslaved by Ephraim G. Ponder, a wealthy slave trader.[2][3][4]: 10

Flipper attended Atlanta University during Reconstruction. There, as a freshman, he was appointed by Representative James C. Freeman to attend West Point, where four other black cadets were already attending. The small group had a difficult time at the academy, where they were rejected by white students. Nevertheless, Flipper persevered, and in 1877, became the first of the group to graduate, earning a commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army cavalry. He was assigned to the 10th Cavalry Regiment,[5] one of the four all-black "buffalo soldier" regiments in the Army, and became the first black officer to command regular troops in the U.S. Army (all-black regiments had been commanded by white officers).[2][non-primary source needed]

10th Cavalry Regiment

[edit]

In July 1877, Flipper reported to Fort Sill in the Indian Territory, for assignment with the 10th Cavalry. But the 10th was not at Fort Sill, they were at Fort Concho. He was not assigned to a cavalry troop, but given work assignments including engineering a ditch to drain a swamp that was malaria-infested. He supervised the construction of roads and telegraph lines. Finally, Flipper received orders to report to Fort Concho in West Texas in October 1877 and was assigned to 'A' Troop. He was the first nonwhite officer to lead buffalo soldiers of the 10th Cavalry.[6]

Captain Nicholas M. Nolan, the commander of 'A' troop, was the officer assigned to teach him about being a cavalry officer. Nolan was censured by several white officers for allowing Flipper into his quarters for dinner, where his daughter Kate was present. Nolan defended his action by stating that Flipper was an "officer and a gentleman" just like any other officer present.[6][7]

In August 1878, Captain Nolan married his second wife, Anne Eleanor Dwyer, in San Antonio, Texas. They had one child, a girl. Anne's sister, Miss Mollie Dwyer, arrived shortly after Troop A moved to Fort Elliott in Texas in early 1879.[7] Mollie Dwyer and Flipper became friends and often went riding together. Nolan was the de facto commander of Fort Elliott and he made Flipper his adjutant. Flipper received high marks from his commander. However, rumors and letters hinted at improprieties against Flipper, an African American and Dwyer, a Caucasian. It was the beginning of a smear campaign. During the next many months, he sent and received letters from Mollie.[6]

In the fall of 1879, a Federal Marshal named Norton, armed with blank warrants, began a quarrel with a county judge. Other county officials stepped in to defend the judge and Norton arrested all of them with his armed men. Norton took the county men to Fort Elliott to be placed in the guardhouse. Nolan was required by law to accept the prisoners, and Nolan apparently talked with the Wheeler County Judge. The telegraph lines then were suddenly cut and Nolan decided to act. Flipper gathered the prisoners in the middle of the night, and with two soldiers, set off for another fort in Indian Territory.[6]

Norton captured the entire party and arrested Flipper and one of his soldiers. The other soldier ran back to the fort to report what had happened. Norton then set off for Dallas, Texas. Nolan mounted a detail of men and took off in pursuit. He caught up to the party and made it clearly known that no prisoners would be shot while trying to escape because the federal marshal and his prisoners were now under military escort. A federal judge dismissed the warrants and Norton filed federal charges of "interfering with the process of the law" against the two officers. The two officers were quickly tried and found guilty. Both were fined $1,000, which was an enormous fine for its time (equivalent to $32,700 in 2023).[8] Norton was satisfied, then left. The federal judge then suspended payment and dismissed the two military officers. Army relations in Wheeler County improved tremendously. Nolan had Flipper under his wing for the first part of the Apache Wars in early 1879 until he was reassigned to G Troop. Until November 1879, during his captain's four-month leave, Flipper commanded this unit by himself and received a well done.[6]

In May 1880, Flipper and Nolan reunited during the Victorio Campaign. It was the last time the two met.[7] Throughout this period, his military career was encumbered by racism in the military, though he did have the support of some officers, such as Nolan, and many of the white civilians he encountered who were impressed by his competency. In the later part of 1880, Flipper was transferred to Fort Davis in West Texas and assigned as the post quartermaster and commissary officer.[6]

End of military career

[edit]Colonel William Rufus Shafter[9] assumed command at Fort Davis in March 1881. He had been the commander of the First Infantry Regiment at Fort Davis. Shafter had a reputation as harassing officers he disliked.[citation needed] Flipper was dismissed without cause as quartermaster within days. Then Shafter "asked" Flipper to keep the quartermaster's safe in his quarters. Being "asked" by a superior officer was a de facto order and Flipper complied. In July 1881, Flipper found a shortage of over $2,000.00 (equivalent to $63,145 in 2023).[8] Realizing this could be used against him by officers intent on forcing him out of the army, he attempted to hide the discrepancy, which was later discovered, and then lied about it when confronted. In August, he was arrested by Shafter for embezzling government funds. Word quickly spread about the missing money. Many felt it was a setup and soldiers and the community came up with the money to replace what was missing within four days. Shafter accepted the money, then convened a court-martial on September 17, 1881.[6]

In December 1881, the court-martial found Flipper innocent of the main charge, but another charge was added during the trial, and he was found guilty "of conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman", and sentenced to be "dismissed from the service of the United States". It was more than a harsh sentence. In two prior situations involving white officers who had been found guilty of embezzlement, neither officer was dismissed nor dishonored. The letters exchanged between Mollie Dwyer (Nolan's sister-in-law) and Flipper were used against Flipper. Relationships between whites and blacks were strictly forbidden in the viewpoint of the white officers on the board. Despite appeals, and with the denial of a lighter sentence from President Chester A. Arthur, Flipper was drummed out of the army with a dismissal, the officer equivalent of a dishonorable discharge, on June 30, 1882. For the rest of his life, Flipper contested the charges and fought to regain his commission.[2][6][7]

After the military

[edit]

After his dismissal, Flipper remained in Texas, working as a civil engineer in El Paso. In 1898, he volunteered to serve in the Spanish–American War, but requests to restore his commission were ignored by Congress. Flipper spent time in Mexico where, according to folklorist J. Frank Dobie, he attempted to discover the location of the legendary lost silver mine of Tayopa. Upon returning to the United States, he served as an adviser to Senator Albert Fall on Mexican politics. When Senator Fall became Secretary of the Interior in 1921, he brought Flipper with him to Washington, D.C., to serve as his assistant.[2]

In 1923, Flipper went to work in Venezuela as an engineer in the petroleum industry. He retired to Atlanta in 1931, and died in 1940.[2] He was buried in the family plot at South-View Cemetery, but in February 1978 he was exhumed and reburied in his home town of Thomasville.[10]

Legacy

[edit]

In 1976, descendants and supporters applied to the Army Board for the Correction of Military Records on behalf of Flipper. The board, after stating it did not have the authority to overturn his court-martial conviction, concluded the conviction and punishment were "unduly harsh and unjust" and recommended that Flipper's dismissal be changed to a good conduct discharge. The Assistant Secretary of the Army (Manpower and Reserve Affairs) and the Adjutant General approved the board's findings, conclusions, and recommendations, and directed the Department of the Army to issue Flipper a Certificate of Honorable Discharge, dated June 30, 1882, in lieu of his dismissal on the same date. On October 21, 1997, a private law firm, Arnold & Porter, filed an application of pardon with the Secretary of the Army on Flipper's behalf. Seven months later, the application was forwarded by the Acting Assistant Secretary of the Army (Manpower and Reserve Affairs) to the Office of the Pardon Attorney at the Department of Justice with a recommendation that the pardon be approved.[citation needed] Many pardon applications had been rejected in the past – as a matter of policy – because the intended recipients were deceased. However, President Bill Clinton pardoned Flipper on February 19, 1999.[2][failed verification]

After his discharge was changed, a bust of Flipper was unveiled at West Point. Since then, an annual Henry O. Flipper Award has been granted to graduating cadets at the academy who exhibit "leadership, self-discipline, and perseverance in the face of unusual difficulties."[2]

Throughout his life, Flipper was a prolific author, writing about scientific topics, the history of the Southwest, and his own experiences. In The Colored Cadet at West Point (1878) he describes his experiences at the military academy. In the posthumous Negro Frontiersman: The Western Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper (1963), he describes his life in Texas and Arizona after his discharge from the Army.[2]

See also

[edit]- James Webster Smith, first black cadet at West Point

- Johnson Chesnut Whittaker (1858–1931), one of the first black men to win an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point

- List of African-American firsts

- List of African-American pioneers in desegregation of higher education

- List of people pardoned by Bill Clinton

- Dreyfus affair

References

[edit] This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. Vol. 14. James T. White & Company. 1910. p. 348. OCLC 1049905558.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ a b c d e f g h The Multiracial Activist – www.multiracial.com – The Colored Cadet at West Point. Autobiography of Lieut. Henry Ossian Flipper Archived December 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine at multiracial.com

- ^ Garrett, Franklin M. (2010) [1954, 1969]. Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of Its People and Events. Vol. I: 1820s–1870s. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. pp. 511–513. doi:10.1353/book11991. ISBN 978-0-8203-3127-0. LCCN 54014260. OCLC 794702320.

- ^ * Dietrichs, John A. (December 2020). "The Ponder House: An Historic Nexus" (PDF). Battle Lines: Newsletter of the Civil War Round Table of Atlanta. 2020 (8). Atlanta, Georgia: Atlanta Civil War Round Table: 2–13 – via atlantacwrt.org & Atlanta History Center.

- ^ Lieutenant Henry Ossian Flipper, U.S. Army 1856–1940 Archived September 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Army. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mobeetie Jail Museum (2009). "Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper". Old Mobeetie Texas Association. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2009.[unreliable source?]

- ^ a b c d Bigelow, John Jr, Lieutenant, U.S.A., R.Q.M. Tenth Cavalry (c. 1890). "'The Tenth Regiment of Cavalry' from 'The Army of the United States Historical Sketches of Staff and Line with Portraits of Generals-in-Chief'". United States Army. Archived from the original on August 3, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Shafter, William Rufus". The Handbook of Texas Online. Archived from the original on March 25, 2011. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- ^ Perry, Harmon (March 23, 1978). "Deceased West Point Grad Honored In Ga. Hometown". Jet. Vol. 54, no. 1. p. 22. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

After 38 years of embedment in an unmarked grave on a family plot alongside distant relatives, the remains of the nation's first Black graduate of the U.S. Army Academy (West Point) were unearthed from the Southview Cemetery in Atlanta and driven 240 miles for....the reburial ceremonies in Thomasville, Feb. 11, 1978

Further reading

[edit]- The Colored Cadet at West Point. Autobiography of Lieut. Henry Ossian Flipper, U.S.A., First Graduate of Color from the U.S. Military Academy. New York: Homer Lee & Co., 1878.

- Works by or about Henry Ossian Flipper at the Internet Archive

- Lieutenant Henry Ossian Flipper, U.S. Army 1856–1940 Archived September 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine at the United States Army Center of Military History

- Additional information on famous presidential pardons Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- Henry O. Flipper Collection Finding Aid at the Archives Research Center of the Robert W. Woodruff Library, Atlanta University Center.

External links

[edit]| Archives at | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| How to use archival material |

- Lt. Flipper: The First Black Graduate of West Point

- Henry O. Flipper Dinner Archived January 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Flipper, Henry O.

- Henry Flipper: Groundbreaking Graduate U.S. Army

- Lt Henry O. Flipper's Quest for Justice

- Fort Concho National Historic Landmark and museum.

- Works by Henry Ossian Flipper at Project Gutenberg

- The Colored Cadet at West Point. Autobiography of Lieut. Henry Ossian Flipper, U.S.A., first graduate of color from the U.S. Military Academy

- Works by Henry Ossian Flipper at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch