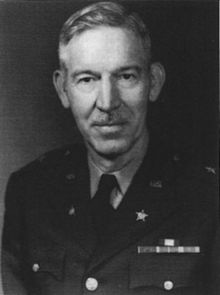

Herbert Loper

Herbert Bernard Loper | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 October 1896 Norcatur, Kansas, United States |

| Died | 25 August 1989 (aged 92) Palm Bay, Florida, United States |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1918–1955 |

| Rank | |

| Service number | 0-12243 |

| Unit | |

| Commands | Armed Forces Special Weapons Project |

| Battles / wars | World War I World War II: |

| Awards | Army Distinguished Service Medal Legion of Merit (2) |

| Other work | Chairman of the Military Liaison Committee |

Major General Herbert Bernard Loper (22 October 1896 – 25 August 1989) was a United States Army officer who helped plan the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign and the Okinawa campaign during World War II. He was chief of the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project from 1952 to 1953, and Chairman of the Military Liaison Committee of the United States Atomic Energy Commission from 1954 to 1961.

A graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, he was commissioned in the US Army Corps of Engineers in 1919. He graduated from the United States Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in 1940, and became Assistant Chief, and later Chief, of the Intelligence Division at the Office of the Chief of Engineers in Washington, DC. In May 1942, he negotiated the Loper-Hotine Agreement, under which responsibility for military mapping and survey of the globe was divided between the United States and the United Kingdom. In 1944, he was appointed Chief Engineer of US Army Forces, Pacific Ocean Areas. In this role he was involved with the planning of the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign and the Okinawa campaign. After the fighting ended, he participated in the Occupation of Japan.

Loper returned to the United States to become Chief of the Joint Photo and Survey Section of the Joint Chiefs of Staff's Joint Intelligence Group in 1948. The next year he was appointed as an Army member of the Military Liaison Committee of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. He wrote a report which became known as the Loper Memorandum, which was influential in the decision to develop thermonuclear weapons. He was Deputy Commander of Joint Task Force 3, which was responsible for the conduct the Operation Greenhouse nuclear tests in the Pacific. In 1951 became Chief of the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project, but was forced to retire after he suffered a heart attack in 1953. He subsequently served as Chairman of the Military Liaison Committee from 2 August 1954 to 14 July 1961.

Early life

[edit]

Herbert Bernard Loper was born in Norcatur, Kansas on 22 October 1896,[1] the son of Gilford (Gilbert) Lafayette Loper and Hulda Belle Scott.[2] He graduated from Washburn College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1916.[3]

Loper was appointed to the United States Military Academy at West Point from Nebraska and entered on 14 June 1917. However, due to World War I, the course was truncated and his class was graduated early on 1 November 1918. He was ranked sixth in the class, two places behind Alfred Gruenther, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant.[4]

After the Armistice with Germany ended the fighting in November 1918, it was decided to have the 1918 class complete their studies. Loper therefore remained at West Point as a student officer until 11 June 1919, when he again graduated, and was assigned to the US Army Corps of Engineers, as was normal for highly placed graduates. At this time, officers who had not served overseas were sent to Europe to tour the battlefields, and Loper visited battlefields in France, Belgium and Italy, as well as the Army of Occupation in Germany.[4]

Between the wars

[edit]Loper returned to the United States in September and was initially posted to Camp A.A. Humphreys, Virginia.[4] He was promoted to first lieutenant on 16 October 1919. In October, he was sent to 8th Engineers at Fort Bliss, Texas. He was stationed at Camp Travis, Texas until June 1920, when he commenced studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, from which he graduated in August 1921,[5] with a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering.[3]

Loper then became Military Assistant to the District Engineer at Jacksonville, Florida. He reverted to the rank of second lieutenant on 15 December 1922, a common enough occurrence in the wake of the demobilization after World War I, but was again promoted to the rank of first lieutenant on 22 April 1923.[5] He married Eleanor Cameron Opie in 1922.[6]

In October 1923, Loper was posted to the 11th Engineers in the Panama Canal Zone. He returned to the United States in December 1926 and was with the Engineer Reproduction Plant at the Army War College until 31 August 1929. He then went back to Camp A. A. Humphreys, first as a student, and then, 1 September 1930, as an instructor.[5] In December 1933, he became Assistant to the District Engineer at Omaha, Nebraska, where he was promoted to captain on 25 May 1935. In February 1938, he was posted to the 6th Engineers at Fort Lawton, Washington.[7]

World War II

[edit]Loper attended the United States Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas from August 1939 to February 1940. On graduation, he was posted to the 7th Engineer Battalion at Fort McClellan, Alabama.[7] He was Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, and then Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4, of the 5th Infantry Division. In June 1940, he became Assistant Chief of the Intelligence Division at the Office of the Chief of Engineers in Washington, DC, and then chief. Here, he was promoted to major on 1 July 1940, lieutenant colonel on 18 September 1941, and colonel on 8 June 1942.[3] In May 1942, he negotiated the Loper-Hotine Agreement, under which responsibility for military mapping and survey of the globe was divided between the United States and the United Kingdom. The agreement also specified technical features such as grids, scales and formats, so Allied servicemen everywhere would have common maps.[8] For his services in this post, he was awarded the Army Distinguished Service Medal on 28 May 1944.[3]

On 28 May 1944, Loper was appointed Chief Engineer of US Army Forces, Pacific Ocean Areas (USAFPOA),[3] on the specific request of the commander of USAFPOA, Lieutenant General Robert C. Richardson, Jr.[9] Loper immediately became involved in planning for the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign. He discovered that the US Navy and Marine Corps did not have adequate map making units, so the task had to be undertaken by the Army. The 64th Topographic Battalion was assigned to the task of mapping the Caroline Islands and Palau. However, until B-29 photographic aircraft could be based in the Mariana Islands, much of the aerial survey had to be carried out by aircraft carrier-based naval aircraft.[10] Later Loper, who was promoted to brigadier general on 11 November 1944,[3] was involved in gathering engineer intelligence for the Battle of Iwo Jima, the Okinawa campaign, and Operation Olympic. When USAFPOA was merged with General of the Army Douglas MacArthur's Southwest Pacific Area in 1945, Loper became Chief of Engineer Intelligence under Major General Hugh J. Casey. After the fighting ended, Loper became Deputy Engineer of United States Far East Command during the Occupation of Japan.[11] For his services in the Pacific, he was awarded the Legion of Merit on 22 September 1945. He was awarded a second Legion of Merit for his services during the Occupation of Japan on 11 September 1948.[3]

Cold War

[edit]Loper returned to the United States in October 1948, to become Chief of the Joint Photo and Survey Section of the Joint Chiefs of Staff's Joint Intelligence Group.[6] On 1 November 1949, he was appointed as an Army member of the Military Liaison Committee of the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC).[12] Following the revelation of the espionage activities of Klaus Fuchs in 1950, Loper and the Chief of the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project, Major General Kenneth D. Nichols, were asked to write a report on the impact of Klaus' activities.[13] Their pessimistic report pessimistically concluded that Soviet Union's nuclear stockpile and production capacity could well be "equal or actually superior to our own, both as to yields and numbers." They added that the Soviets might develop, or had already developed, thermonuclear weapon. The Loper Memorandum, as it became known, was influential in persuading the Joint Chiefs, the Secretary of Defense, and ultimately the President to authorize a crash program to develop thermonuclear weapons.[14]

In 1951, Loper was Deputy Commander of Joint Task Force 3, which was responsible for the conduct the Operation Greenhouse nuclear tests in the Pacific.[15] In 1951, he succeeded Nichols as Chief of the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project. Nichols considered that Loper was "a very capable engineer, easygoing but firm, and well liked by his associates."[16] However, his term in the post was cut short in 1953 when he suffered a heart attack,[17] and he was ultimately forced to retire from the Army in 1955.[1] However, he served as Chairman of the Military Liaison Committee from 2 August 1954 to 14 July 1961.[18] He was also a consultant to the AEC and the Secretary of Defense.[6]

Later life

[edit]In the early 1960s, Loper worked for Washington Associates, a Washington, DC, consulting firm. He had lived in Bozman, Maryland, for 28 years. His wife died in 1979, and he entered a nursing home in Palm Bay, Florida September 1988, and died there of cardiac arrest on 25 August 1989. He was survived by his two sons, Herbert Bernard Loper II and Thomas C. Loper, a retired Army colonel.[6]

Decorations

[edit]- Legion of Merit for services a Chief, Military Intelligence Division, Office of the Chief of Engineers.

- Distinguished Service Medal for services as Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas

- Legion of Merit (Oak Leaf Cluster) for services as Chief, Engineer Division, Office of the Chief of Engineers, General Headquarters, United States Armed Forces, Pacific.

- Honorary Commander of the Order of the British Empire for service as Chief, Military Intelligence Division, Office of the Chief of Engineers.

- Campaign Star: Western Pacific Campaign

- Campaign Star: Southern Philippine Campaign

Bibliography

[edit]- Ancell, R. Manning; Miller, Christine (1996). The Biographical Dictionary of World War II Generals and Flag Officers: The US Armed Forces. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 457. ISBN 0-313-29546-8. OCLC 231681728.

- Brahmstedt, Christian (2002). Defense's Nuclear Agency, 1947–1997 (PDF). DTRA history series. Washington, D.C.: Defense Threat Reduction Agency, US Department of Defense. OCLC 52137321. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Casey, Hugh J., ed. (1948), Volume III: Engineers Intelligence, Engineers of the Southwest Pacific 1941–1945, Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Army, OCLC 9698691

- Dod, Karl (1966). The Corps of Engineers: The War Against Japan. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Army. OCLC 396169.

- Cullum, George W. (1920). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume VI 1910–1920. Chicago: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Cullum, George W. (1930). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume VII 1920–1930. Chicago: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Cullum, George W. (1940). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume VIII 1930–1940. Chicago: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Cullum, George W. (1950). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume IX 1940–1950. Chicago: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Duncan, Francis (1969). Atomic Shield, 1947–1952. A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07187-5. OCLC 3717478.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Holl, Jack M. (1989). Atoms for Peace and War, Volume III, 1953–1961 Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission. A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-06018-0. OCLC 18739933.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ancell & Miller 1996, p. 193.

- ^ "Herbert Bernard Loper (1896 - 1989)". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cullum 1950, p. 302.

- ^ a b c Cullum 1920, p. 2064.

- ^ a b c Cullum 1930, p. 1423.

- ^ a b c d "Gen. Herbert B. Loper Dies; Atomic Energy Liaison Chief". The Washington Post. 30 August 1989. p. METRO d.07.

- ^ a b Cullum 1940, p. 415.

- ^ Casey 1948, p. 23.

- ^ Dod 1966, p. 491.

- ^ Dod 1966, p. 510.

- ^ Dod 1966, p. 668.

- ^ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, p. 666.

- ^ Hewlett & Duncan 1969, p. 415.

- ^ Brahmstedt 2002, p. 76.

- ^ Cullum 1950, p. 320.

- ^ Brahmstedt 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Brahmstedt 2002, p. 99.

- ^ Hewlett & Holl 1989, p. 573.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch