Hernán Pérez de Quesada

Hernán Pérez de Quesada | |

|---|---|

Hernán, as Spanish conquistador, wore an armoured uniform | |

| Born | c. 1515 |

| Died | 1544 |

| Cause of death | Lightning strike |

| Nationality | Castilian |

| Occupation | Conquistador |

| Years active | 1536–1542 |

| Employer | Spanish Crown |

| Known for | Spanish conquest of the Muisca Quest for El Dorado |

| Title | Governor of New Kingdom of Granada |

| Term | 1539–1542 |

| Predecessor | Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada (1538–1539) |

| Successor | Luis Alonso de Lugo (1542–1544) |

| Criminal charge(s) | • Mistreatment of indigenous people • Murders of Tisquesusa, Sagipa & Aquiminzaque |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Gonzalo Jiménez (brother) Francisco Jiménez (brother) Melchor Jiménez (brother) Andrea Ximénez (sister) Catalina Magdalena (sister) Isabel de Quesada (half-sister) |

| Notes | |

Hernán Pérez de Quesada, sometimes spelled as Quezada,[7] (c. 1515 – 1544) was a Spanish conquistador. Second in command of the army of his elder brother, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, Hernán was part of the first European expedition towards the inner highlands of the Colombian Andes. The harsh journey, taking almost a year and many deaths, led through the modern departments Magdalena, Cesar, Santander, Boyacá, Cundinamarca and Huila of present-day Colombia between 1536 and 1539 and, without him, Meta, Caquetá and Putumayo of Colombia and northern Peru and Ecuador between 1540 and 1542.

Hernán founded Sutatausa, Cundinamarca, and aided in the conquest of various indigenous groups, such as the Chimila, Muisca, Panche, Lache, U'wa, Sutagao and others. Under the command of Hernán Pérez de Quesada the last independent Muisca ruler; hoa Quiminza was publicly decapitated. As second in command under his brother, in the previous years psihipquias Tisquesusa and Sagipa and Tundama of Duitama had suffered a similar fate. After returning from his expeditions to the south reaching Quito, where he reunited with his younger brother Francisco, both De Quesadas went back to Santafé de Bogotá. Hernán was tried and imprisoned there for the murders of the Muisca rulers by the governor of the capital of the New Kingdom of Granada. In 1544, en route to Cartagena with his brother Francisco, their ship was hit by lightning off the coast of Cabo de la Vela in the Caribbean Sea killing Hernán and Francisco and wounding several other conquistadors.

Knowledge of the life and expeditions of Hernán Pérez de Quesada has been provided by his brother Gonzalo and scholars Pedro de Aguado, Juan Freyle, Lucas Fernández de Piedrahita, Joaquín Acosta and Liborio Zerda.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

Biography

[edit]

Early life

[edit]Hernán Pérez de Quesada was born around the year 1512 in the Andalusian city of Granada as second son of Gonzalo Jiménez and Isabel Jiménez de Quesada.[1][2][3] His family was Catholic, but descended from marranos (Sephardi Jews).[14] His elder brother was conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez and he had four other siblings; brother Melchor, Francisco, who also was conquistador in Peru, and sisters Magdalena de Quesada and Andrea Ximénez de Quesada.[3][4][5] Hernán also had a half-sister; Isabel de Quesada.[6] In 1535, arriving early 1536, the brothers Gonzalo, Francisco and Hernán sailed from Spain to Santa Marta, one of the first cities founded in modern-day Colombia, by Rodrigo de Bastidas in 1525.

Conquest in Colombia

[edit]

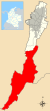

Hernán Pérez de Quesada accompanied his elder brother along the green route from 1536 to 1538.

Between 1540 and 1542 Hernán first went north of Sogamoso and then southeast to Caquetá and Putumayo and southwest through northern Peru, terminating in Quito.

Hernán and his younger brother Francisco died in the Caribbean Sea, off the coast of Cabo de la Vela, the northeastern peninsula of Colombia

1536 - the harsh route towards Muisca territory

[edit]

The first indigenous group that was submitted to the Spanish Crown were the Tairona, who inhabit the area around Santa Marta, presently living on the slopes of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and in Tayrona Park. On April 6, 1536, triggered by the stories of the mythical "City of Gold" El Dorado, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada organised two groups of conquistadors towards the inner highlands of the Colombian Andes, as first European explorers.[3] The army with the brothers De Quesada and more than 700 soldiers and 80 horses went over land and another, of more than 200 men, embarked in boats and ascended the Magdalena River from Ciénaga, in search of its origin. The list of the soldiers that eventually made it to Funza has been compiled by Juan Florez de Ocáriz (1612–1692).[15] The land army was led by Gonzalo with Hernán second in command.[16] The first indigenous group conquered, were the Chimila people. Continuing south, the troops had to cross inhospitable terrains full of creeks and part of their supplies and equipment was lost when crossing the Ariguaní River.[17]

The troops led by the De Quesadas passed through among other settlements Tamalameque, Barrancabermeja and Chipatá where the Spanish for the first time learnt to drink chicha, the fermented alcoholic beverage of the Muisca. The almost-naked conquistadors who suffered from the difficult expedition through the jungles received cotton mantles from the Muisca people in Chipatá. The expedition passed through halted in Chía where they spent the Holy Week. After that week in April 1537, he ordered his men towards Funza, the site of the domain of the zipa. Although the army of the brothers De Quesada was reduced to 170 men, the hundreds of guecha warriors couldn't resist their superior arms and were defeated. In the meantime, zipa Tisquesusa sent messengers to the caciques in the Muisca Confederation to inform them of the arrival of the light-skinned heavily armed men. The caciques considered the invaders sacred and didn't dare to attack them.[17] Funza was conquered and founded on April 20, 1537.[18] Of the more than 900 soldiers who left Santa Marta a year earlier, only 162 survived the harsh expedition.[15]

On the same day that his brother Gonzalo founded Tenza, June 24, 1537, Hernán founded Sutatausa.[19]

First conquest by Hernán Pérez de Quesada

[edit]| Name | Department | Date | Year | Notes | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sutatausa | Cundinamarca | 24 June | 1537 | [19] |  |

1538 - establishment of Bogotá and surroundings

[edit]At the start of 1538, when the troops were exhausted after almost two years in foreign terrain, the soldiers asked what was their payment for the conquest they had done. De Quesada divided the conquered treasures over his men; 40,000 pieces of fine gold, 562 emeralds and tumbaga (gold-copper-silver alloys). Foot soldiers received 520 pieces each, horse riders the double amount, captains 2080 pieces, generals 3640 and some pieces were given as prizes for the most distinguished soldiers. Masses were organised to honour the many dead soldiers during the campaign and part of the treasure was given to Juan de las Casas. De Quesada was not pleased to hear about the advancement of another group of conquistadors in the east, led by Nikolaus Federmann, coming from later Venezuela across the Llanos Orientales. Another team of conquerors, commanded by Sebastián de Belalcázar, was coming from the south, originating from Quito. Gonzalo sent Hernán to meet the southern group who had traveled through the hot valley of Neiva.[17] Hernán ordered the decapitation of Aquiminzaque, the last zaque of Hunza in late 1538.[20]

Foundation of Bogotá

[edit]One and a half year after the victory of the conquistadors on Tisquesusa, in the area of Teusaquillo, the modern capital of Colombia was founded. Although some historians set the date at April 27, 1539, the common and celebrated date of foundation is August 6, 1538. The foundation was performed by the construction of 12 houses of reed, referring to the Twelve Apostles, and the construction of a preliminary church, also of reed. Father Juan de las Casas held his first mass in the improvised church. The city was named Santafé de Bogotá, a combination of the Spanish city of Santa Fe and the Chibcha name of the southern Muisca capital Bacatá, meaning "Enclosure outside of the farmfields".[21] The newly established country, part of the Spanish Empire was called New Kingdom of Granada, after the place of birth of the brothers De Quesada in Andalusia; Kingdom of Granada.[17]

Return to Spain of Gonzalo, Sebastián and Nikolaus

[edit]The three leaders of the conquest expeditions; Gonzalo de Quesada, Nikolaus Federmann and Sebastián de Belalcázar, met in Bosa and agreed to travel back to Spain to ask for compensation for their exploration for the Spanish Crown. Gonzalo assigned Hernán as interim governor of the New Kingdom and chose the first mayor and council for the capital. The chaplain of the team of Federmann, Juan Verdejo, was named priest. Most of the soldiers of the expeditions of Federmann and De Belalcázar decided to stay in Bogotá, reinforcing the troops of De Quesada. Without having found El Dorado, three years after his departure from Santa Marta, in mid May 1539, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada returned to the Caribbean coast, to sail to Spain from Cartagena.[17]

Hernán in charge of the New Kingdom of Granada

[edit]1540–1541

[edit]In his search for El Dorado, Hernán explored the departments of Tolima and Huila.[1] Hernán Pérez de Quesada was only one of many explorers in the search for El Dorado.[22] After the destruction and looting of the Sun Temple in Sogamoso in September 1537, Hernán Pérez thought there was an even bigger place where the indigenous people hid their gold, called "La Casa del Sol". In his quest, starting from Sogamoso along the right banks of the Chicamocha River, he approached with a hundred men the terrain of the Lache and entered Jericó, at that time called Cheva, where he and his troops gathered the food of the original inhabitants who promptly fled to Chita.[23]

The city of Tunja, in the times of the Muisca called Hunza, was founded on 1541 by Gonzalo Suárez Rendón in an expedition ordered by Hernán de Quesada.[24] In July 1541, the Chapter of Tunja told De Quesada that he couldn't leave his empire alone. Hernán responded that "whatever he did, was in the interest of the Spanish Crown".[25]

Later in 1541, Hernán Pérez de Quesada went northward towards the later department of Norte de Santander, where he crossed Panqueba, Guacamayas, El Cocuy and Chita, and reached Chinácota but had to return soon after that.[26][27] Soldiers of his army submitted the U'wa living in El Cocuy.[28]

On his southern expedition in the same year, Hernán Pérez de Quesada was the first European to reach the southeastern Colombian departments of Caquetá and Putumayo.[24] One of his soldiers, Lázaro Fonte, the lover of Zoratama, died due to the natural dangers of the jungle.[29]

Second conquest by Hernán Pérez de Quesada

[edit]| Name | Department | Date | Year | Notes | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motavita | Boyacá | 1540 | [7] |  | |

| Sasaima | Cundinamarca | Early | 1540 | [30] |  |

| Bituima | Cundinamarca | 1540 | [31] |  | |

| Nimaima | Cundinamarca | 1540 | [32] |  | |

| Sativasur | Boyacá | 1540 | [33] |  | |

| Jericó | Boyacá | 1540 | [34] |  | |

| Guacamayas | Boyacá | 1540 | [35] |  | |

| Chiscas | Boyacá | 1540 | [36] |  | |

| Chita | Boyacá | 1540 | [35] |  | |

| Panqueba | Boyacá | 1540 | [35] |  | |

| Güicán | Boyacá | 1540 | [37] |  | |

| El Cocuy | Boyacá | 1540 | [35][38] |  | |

| Pasca | Cundinamarca | Early September | 1540 | [9] |  |

| Nevado del Sumapaz | Cundinamarca | 1540 |  | ||

| San Martín | Meta | 1540 | [39] |  | |

| Florencia | Caquetá | 1540 | [40] |  | |

| San José de la Fragua | Caquetá | 1540 | [9] |  | |

| Mocoa | Putumayo | 1540–41 | [9] |  | |

| Sibundoy | Putumayo | 1541 | [9] |  | |

| Popayán | Cauca | 1541 | [9] |  | |

| Cali | Valle del Cauca | 1541 | [41] |  | |

| Quito | Pichincha | 1542 |  |

Reunion with his brother Francisco and death

[edit]De Quesada reached Peru with an army of 500 men having failed to find the mythical El Dorado.[25] In 1542 he reached the Kingdom of Quito where he joined his brother Francisco.[16] The brothers returned to Bogotá, where Hernán was tried and imprisoned by Luis Alonso de Lugo, the new governor of the capital, for his mistreatment of the indigenous peoples and the murders of Saymoso, Quiminza, Tisquesusa and Sagipa. In 1544 Hernán and Francisco embarked on a ship from Santo Domingo to Cartagena. Lightning struck the ship off the coast of Cabo de la Vela; both brothers died along with several other conquistadors and the Bishop of Santa Marta, friar Martín de Calatayud.[1]

See also

[edit]- List of conquistadors in Colombia

- Spanish conquest of the Muisca

- El Dorado

- Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d (in Spanish) Fundaciones antecedentes a la conquista de la aldea Chicamocha

- ^ a b Isabel de Rivera Quesada - Geni.com

- ^ a b c d (in Spanish) Biography Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine - Banco de la República

- ^ a b (in Spanish) El enigma de la espada de Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada - El Espectador

- ^ a b (in Spanish) Familia Berrio y Jiménez de Quesada

- ^ a b Isabel de Quesada - Geni.com

- ^ a b (in Spanish) Official website Motavita

- ^ (in Spanish) Las sociedades indígenas de los Llanos Archived 2017-10-29 at the Wayback Machine - Banco de la República

- ^ a b c d e f Rodríguez Freyle, 1979 (1638), p.93

- ^ (in Spanish) Historia general de las conquistas del Nuevo Reyno de Granada Archived 2016-05-04 at the Wayback Machine - National Library of Colombia

- ^ (in Spanish) Cómo era Hernán Pérez de Quesada Archived 2016-08-08 at the Wayback Machine - Banco de la República

- ^ Acosta, 1848

- ^ Zerda, 1883

- ^ Tenenbaum, Barbara A.; Dorn, Georgette M. (1996), Encyclopedia of Latin American history and culture, New York: C. Scribner's Sons, p. 332, ISBN 0-684-19253-5

- ^ a b (in Spanish) List of conquistadors led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada Archived 2016-03-09 at the Wayback Machine - Banco de la República

- ^ a b (in Spanish) Biography Hernán Pérez de Quesada Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine - Banco de la República

- ^ a b c d e (in Spanish) Conquista rápida y saqueo cuantioso de Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Funza Archived 2015-12-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b (in Spanish) Official website Sutatausa Archived 2016-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Spanish) Public execution of Aquiminzaque in Tunja Archived 2016-02-06 at the Wayback Machine - Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas

- ^ (in Spanish) Etymology Bacatá Archived 2016-10-07 at the Wayback Machine - Banco de la República

- ^ (in Spanish) Expeditions El Dorado

- ^ (in Spanish) Jericó, un municipio de altura - El Tiempo

- ^ a b (in Spanish) Hernán Pérez de Quesada Archived 2017-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kupchick, 2008, p.132

- ^ (in Spanish) Cúcuta - fundadores y exploradores Archived 2016-08-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Spanish) Guacamayas

- ^ (in Spanish) El Cocuy, tierra de nieve y sol - El Tiempo

- ^ Ocampo López, 1996, p.103

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Sasaima

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Bituima[permanent dead link]

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Nimaima

- ^ (in Spanish) History Sativasur

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Jericó

- ^ a b c d (in Spanish) Official website Guacamayas

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Chiscas[permanent dead link]

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Güicán

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website El Cocuy

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website San Martín Archived 2014-03-18 at archive.today

- ^ (in Spanish) Official website Florencia Archived 2016-05-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rodríguez Freyle, 1979 (1638), p.94

Bibliography

[edit]- Acosta, Joaquín (1848), Compendio histórico del descubrimiento y colonización de la Nueva Granada en el siglo décimo sexto - Historical overview of discovery and colonization of New Granada in the sixteenth century, Paris: Beau Press, pp. 1–460, OCLC 23030434, retrieved 2016-07-08

- Rodríguez Freyle, Juan; Achury Valenzuela, Darío (1979) [1859 (1638)], El Carnero - Conquista i descubrimiento del nuevo reino de Granada de las Indias Occidentales del mar oceano, i fundacion de la ciudad de Santa Fe de Bogota (PDF) (in Spanish), Fundacion Biblioteca Ayacuch, pp. 1–598, retrieved 2016-11-21

- Kupchick, Christian (2008), La leyenda de El Dorado y otros mitos del Descubrimiento de América: La auténtica historia de la búsqueda de riquezas y reinos fabulosos en el Nuevo Mundo (in Spanish), Ediciones Nowtilus S.L, pp. 1–304, ISBN 9788497635646, retrieved 2016-07-08

- Ocampo López, Javier (1996), Leyendas populares colombianas - Popular Colombian legends (in Spanish), Plaza y Janes Editores, pp. 1–384, ISBN 9789581402670, retrieved 2016-07-08

- Zerda, Liborio (1947) [1883], El Dorado (PDF) (in Spanish), archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-07, retrieved 2016-07-08

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch