Historic desertification

Historic desertification is the study of the desert-forming process from a historic perspective. It was presumed in the past that the main causes of desertification lay in overuse of the land resulting in impoverishment of the soil, reduced vegetation cover, increased risk of drought and the resulting wind erosion. However recent projects to regreen deserts have not met with the success envisaged, and cast doubts on this theory. Research suggests that it is extreme events rather than drought caused by low annual precipitation, that do the most damage. Heavy downpours resulting in flash floods wash away sediment and there seems to have been an increased number of extreme events in the Levant at the end of the Byzantine period. The decline of settlements in the desert belt at this time may have been caused by these extreme events rather than a reduction in annual precipitation.

Causes of desertification

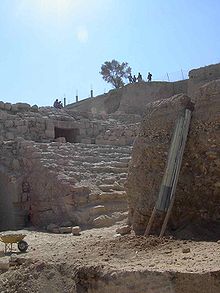

[edit]The Mediterranean and its transition zones to the deserts are characterized by impressive Roman and Byzantine ruins, which are subject of discussion as to how these cities came to be deserted. It was assumed that population growth or conquest by nomadic tribes led to over-exploitation of the land, leading to soil erosion and irreversible degradation. Reduced soil and vegetation cover led to reduced precipitation and advancing deserts.[1]

However, failure of development aid projects raised doubts about the validity of the historic desertification issue. For example, a project aiming to reduce sedimentation and erosion at the King-Talal-dam close to Jerash in Jordan could not achieve its goals, which became clear when a heavy rainstorm led to massive sedimentation into the dam despite the newly constructed soil conservation devices. As well, the expected positive effects of the reforestation could not be observed. On the contrary, a high fire risk emerged since pine trees are easily flammable, and the grazing pressure was moved towards more sensitive areas in the desert belt. The evergreen trees also reduced groundwater recharge.[2]

Research

[edit]A number of running research projects in Jordan found that the erosion of the main agricultural soil, the Terra Rossa, took place at the end of the last ice age and during the Younger Dryas. It seems therefore that erosion of the today's intensively used soils was limited during historical periods, and not connected with desertification.[3]

The discussion about the impact of climate change on desertification focuses on drought. While some authors argue that periods of decline in the Levant were synchronous with reduced rainfall, others point to the non-linear development of settlement. However, a focus on annual precipitation allows only for limited conclusions about the productivity of agriculture. In this context, soils and colluvia point to an increased frequency of extreme rainfall events in the Levant at the end of the Byzantine period. As far as such events could be observed today, their associated damage was always enormous and could have had much more serious consequences than drought. The decline of settlement in the desert belt at the end of antiquity could be connected with an increase of extreme events.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ Lowdermilk, W (1944). Palestine – land of promise. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Grove, A; Rackham, Oliver (2003). The Nature of Mediterranean Europe: an Ecological History.

- ^ Schmidt, M; Lucke, B; Bäumler, R; al-Saad, Z; al-Qudah, B; Hutcheon, A (2006). "The Decapolis region (Northern Jordan) as historical example of desertification? Evidence from soil development and distribution". Quaternary International. 151 (1): 74–86. Bibcode:2006QuInt.151...74S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2006.01.023.

- ^ Lucke, B (2007). "Demise of the Decapolis. Past and Present Desertification in the Context of Soil Development, Land Use, and Climate".

Further reading

[edit]- Beaumont, P., 1985. "Man-induced erosion in northern Jordan." Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan 2, 291-296.

- Cordova, C., Foley, C., Nowell, A., Bisson, M., 2005, "Landforms, sediments, soil development and prehistoric site settings in the Madaba-Dhiban Plateau, Jordan", Geoarchaeology, Vol. 20 No. 1, 29-56.

- Dracup, J., 1987, "Climatic Change, Hydrology, and Water Management in Arid Lands"", in: Berkofsky, L., Wurtele, G. (Hg.), 1987, Progress in Desert Research, Totowa, 217-228.

- Dregne, H., 1983, "Desertification of Arid Lands", Advances in Desert and Arid Land Technology and Development, Vol. 3, London.

- Field, J., Banning, E, 1998, "Hillslope processes and archaeology in Wadi Ziqlab, Jordan", Geoarchaeology, Vol. 13, No. 6, 595-616.

- Hazan, N., Stein, M., Agnon, A., Marco, S., Nadel, D., Negendank, J., Schwab, M., Neev, D., 2005, "The late Quaternary limnological history of Lake Kinneret (Sea of Galilee), Israel", Quaternary Research 63, 60-77.

- Lamb, H., 1982, Climate, History and the Modern World, London.

- Maher, L., 2005, The Epipaleolithic in context: paleolandscapes and prehistoric occupation in Wadi Ziqlab, Northern Jordan, Dissertation, University of Toronto.

- Migowski, C., Stein, M., Prasad, S., Negendank, J., Agnon, A., 2006, "Holocene climate variability and cultural evolution in the Near East from the Dead Sea sedimentary record", Quaternary Research 66 (3), 421-431.

- Müller, J., Bolte, A., Beck, W., Anders, S., 1998, "Bodenvegetation und Wasserhaushalt von Kiefernforstökosystemenen (Pinus sylvestris L.)", Verhandlungen der Gesellschaft für Ökologie 28, 407-414.

- Rosen, A., 2007, Civilizing Climate. Social Responses to Climate Change in the Ancient Near East. New York City.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch