History of New Spain

The history of mainland New Spain spans three hundred years from the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519–21) to the collapse of Spanish rule in the Mexican War of Independence (1810–21).

Beginning with the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521 by Hernán Cortés, Spanish rule was established, leading to the creation of governing bodies like the Council of the Indies and the Audiencia to maintain control. The initial period involved the forced conversion of indigenous populations to Catholicism and the blending of Spanish and indigenous cultures.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Spanish settlers founded major cities such as Mexico City, Puebla, and Guadalajara, turning New Spain into a vital part of the Spanish Empire. The discovery of silver in Zacatecas and Guanajuato significantly boosted the economy, leading to conflicts like the Chichimeca War. Missions and presidios were established in northern frontiers, aiding in the expansion and control of territories that are now part of the southwestern United States. The 18th century saw the implementation of the Bourbon Reforms, which aimed to modernize and strengthen the colonial administration and economy. These reforms included the creation of intendancies, increased military presence, and the centralization of royal authority. The expulsion of the Jesuits and the establishment of economic societies, were part of these efforts to enhance efficiency and revenue for the crown.

The decline of New Spain culminated in the early 19th century with the Mexican War of Independence. Following Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla's 1810 Cry of Dolores, the insurgent army waged an eleven-year war against Spanish rule. The eventual alliance between royalist military officer Agustín de Iturbide and insurgent leader Vicente Guerrero led to the successful campaign for independence. In 1821, New Spain officially became the independent nation of Mexico, ending three centuries of Spanish colonial rule.

Conquest era (1521–1535)

[edit]

The Caribbean islands and early Spanish explorations around the circum-Caribbean region had not been of major political, strategic, or financial importance until the conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521. However, important precedents of exploration, conquest, and settlement and crown rule had been initially worked out in the Caribbean, which long affected subsequent regions, including Mexico and Peru.[1]

The indigenous societies of Mesoamerica brought under Spanish control were of unprecedented complexity and wealth compared to what the conquerors had encountered in the Caribbean. This presented both an important opportunity and a potential threat to the power of the Crown of Castile, since the conquerors were acting independent of effective crown control. The societies could provide the conquistadors, especially Hernán Cortés, a base from which the conquerors could become autonomous, or even independent, of the Crown.

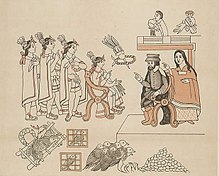

Cortés had already defied orders that curtailed his ambition of an expedition of conquest. He was spectacularly successful in gaining indigenous allies against the Aztec Empire, with the indispensable aid of indigenous cultural translator, Marina, also known as Malinche, toppling the rulers of the Aztec empire. Cortés then divvied up the spoils of war without crown authorization, including grants of labor and tribute of groups of indigenous, to participants in the conquest.

As a result, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, Charles V created the Council of the Indies[Note 1] in 1524 as the crown entity to oversee the crown's interests in the New World. Since the time of the Catholic Monarchs, central Iberia was governed through councils appointed by the monarch with particular jurisdictions. The creation of the Council of the Indies became another, but extremely important, advisory body to the monarch.

The crown had already created the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) in 1503 to regulate contacts between Spain and its overseas possessions. A key function was to gather information about navigation to make trips less risky and more efficient. Philip II sought systematic information about his overseas empire and mandated reports, known as the Relaciones geográficas, describing topography, economic conditions, and populations, among other information. They were accompanied by maps of the area discussed, many of which were drawn by indigenous artists.[2][3][4][5][6] The Francisco Hernández Expedition (1570–77), the first scientific expedition to the New World, was sent to gather information on medicinal plants and practices.[7]

The crown created the first mainland high court, or Audiencia, in 1527 to regain control of the administration of New Spain from Cortés, who as the premier conqueror of the Aztec empire, was ruling in the name of the king but without crown oversight or control. An earlier Audiencia had been established in Santo Domingo in 1526 to deal with the Caribbean settlements. That court, housed in the Casa Reales in Santo Domingo, was charged with encouraging further exploration and settlements with the authority granted it by the crown. Management by the Audiencia, which was expected to make executive decisions as a body, proved unwieldy. In 1535, Charles V of Spain appointed Don Antonio de Mendoza as the first Viceroy of New Spain, an aristocrat loyal to the crown, rather than the conqueror Hernán Cortés, who had embarked on the expedition of conquest and distributed spoils of the conquest without crown approval. Cortés was instead awarded a vast, entailed estate and a noble title.

Catholicism evangelization

[edit]

Spanish conquerors saw it as their right and their duty to convert indigenous populations to Catholicism. Because Catholicism had played such an important role in the Reconquista (Catholic reconquest) of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims, the Catholic Church in essence became another arm of the Spanish government, since the crown was granted sweeping powers over ecclesiastical affairs in its overseas territories. The Spanish Crown granted it a large role in the administration of the state, and this practice became even more pronounced in the New World, where prelates often assumed the role of government officials. In addition to the Church's explicit political role, the Catholic faith became a central part of Spanish identity after the conquest of last Muslim kingdom in the peninsula, the Emirate of Granada, and the expulsion of all Jews who did not convert to Catholicism.

The conquistadors brought with them many missionaries to promulgate the Catholic religion. Amerindians were taught the Catholic religion in their natives languages. Initially, the missionaries hoped to create a large body of Amerindian priests, but were not successful. They did work to keep the Amerindian cultural aspects that did not violate the Catholic traditions, and a syncretic religion developed. Most Spanish priests committed themselves to learn the most important Amerindian languages (especially during the 16th century) and wrote grammars so that the missionaries could learn the languages and preach in them. This was similar to practices of French colonial missionaries in North America.

At first, conversion of indigenous peoples seemed to happen rapidly. The missionaries soon found that most of the natives had simply adopted "the god of the heavens," as they called the Christian God, as another one of their many gods.[citation needed] While they often held the Christian God to be an important deity because he was the God of the victorious conquerors, they did not see the need to abandon their old beliefs. As a result, a second wave of missionaries began an effort to completely erase the old beliefs, which they associated with the ritualized human sacrifice found in many of the native religions. They eventually prohibited this practice, which had been common before Spanish colonization. In the process many artifacts of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture were destroyed. Hundreds of thousands of native codices were burned, native priests and teachers were persecuted, and the temples and statues of the old gods were torn down. The missionaries even prohibited some foods associated with the native religions, such as amaranth.

Many clerics, such as Bartolomé de las Casas, also tried to protect the natives from de facto and actual enslavement to the settlers, and obtained from the Crown decrees and promises to protect native Mesoamericans, most notably the New Laws. But the royal government was too far away to fully enforce these, and settler abuses against the natives continued, even among the clergy. Eventually, the Crown declared the natives to be legal minors and placed under the guardianship of the Crown, which was responsible for their indoctrination. It was this status that barred the native population from the priesthood.

During the following centuries, under Spanish rule, a new culture developed that combined the customs and traditions of the indigenous peoples with that of Catholic Spain. The Spaniards and natives had numerous churches and other buildings constructed in the Spanish style, and named their cities after various saints or religious topics, such as San Luis Potosí (after Saint Louis) and Vera Cruz (the True Cross).

The Spanish Inquisition, and its New Spanish counterpart wasn't powerful, the Mexican Inquisition, continued to operate in the viceroyalty until Mexico declared its independence in 1821. This resulted in the execution of more than 30 people during the virreinal period. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Inquisition worked with the viceregal government to block the diffusion of liberal ideas during the Enlightenment, as well as the revolutionary republican and democratic ideas of the United States War of Independence and the French Revolution.

Sixteenth-century founding of Spanish cities

[edit]

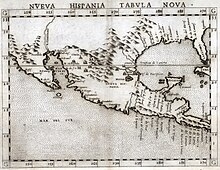

During the first twenty years after the conquest, before the establishment of the viceroyalty, some of the important cities of the colonial era that remain important today were founded. Even before the 1535 establishment of the viceroyalty of New Spain, conquerors in central Mexico founded new Spanish cities and embarked on further conquests, a pattern that had been established in the Caribbean.[8] In central Mexico, they transformed the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan into the main settlement of the territory. Thus, the history of Mexico City is of huge importance to the whole colonial enterprise.

Spaniards founded new settlements in Puebla de los Angeles (founded 1531) at the midway point between the Mexico City (founded 1521–24) and the Caribbean port of Veracruz (1519). Colima (1524), Antequera (1526, now Oaxaca City), and Guadalajara (1532) were all new Spanish settlements. North of Mexico City, the city of Querétaro was founded (ca. 1531) in a region known as the Bajío, a major zone of commercial agriculture.[9]

Guadalajara was founded northwest of Mexico City (1531–42) and became the dominant Spanish settlement in the region. West of Mexico City the settlement of Valladolid (Michoacan) was founded (1529–41). In the densely populated indigenous South, as noted, Antequera (1526) became the center of Spanish settlement in Oaxaca; Santiago de Guatemala was founded in 1524; and in Yucatán, Mérida (1542) was founded inland, with Campeche founded in 1541 as a small, Caribbean port. Sea trade flourished between Campeche and Veracruz.[10]

The discovery of silver in Zacatecas in the far north was a transformative event in the history of New Spain and the Spanish Empire, with silver becoming the primary driver of the economy. The city of Zacatecas was founded in 1547 and Guanajuato, the other major mining region, was founded in 1548, deep in the territory of the nomadic and fierce Chichimeca, whose resistance to Spanish presence became known as the protracted conflict of the Chichimeca War. The silver was so valuable to the crown that waging a fifty-year war was worth doing.[11][12] Other Spanish cities founded before 1600 were the Pacific coast port of Acapulco (1563), Durango (1563), Saltillo (1577), San Luis Potosí (1592), and Monterrey (1596). The cities were outposts of European settlement and crown control, while the countryside was almost exclusively inhabited by the indigenous populations.

Later mainland expansion

[edit]

During the 16th century, many Spanish cities were established in North and Central America. Spain attempted to establish missions in what is now the southern United States, including Georgia and South Carolina between 1568 and 1587. These efforts were mainly successful in the region of present-day Florida, where the city of St. Augustine was founded in 1565. It is the oldest European city in the United States.

Upon his arrival, Viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza vigorously took to the duties entrusted to him by the king and encouraged the exploration of Spain's new mainland territories. He commissioned the expeditions of Francisco Vásquez de Coronado into the present day American Southwest in 1540–1542. The Viceroy commissioned Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in the first Spanish exploration up the Pacific Ocean in 1542–1543.

Cabrillo sailed far up the coast, becoming the first European to see present-day California, now part of the United States. The Viceroy also sent Ruy López de Villalobos to the Spanish East Indies in 1542–1543. As these new territories became controlled, they were brought under the purview of the Viceroy of New Spain. Spanish settlers expanded to Nuevo Mexico, and the major settlement of Santa Fe was founded in 1610.

The establishment of religious missions and military presidios on the northern frontier became the nucleus of Spanish settlement and the founding of Spanish towns.

Pacific expansion and the Philippine trade

[edit]

Seeking to develop trade between the East Indies and the Americas across the Pacific Ocean, Miguel López de Legazpi established the first Spanish settlement in the Philippine Islands in 1565, which became the town of San Miguel (present-day Cebu City). Andrés de Urdaneta discovered an efficient sailing route from the Philippine Islands to Mexico which took advantage of the Kuroshio Current. In 1571, the city of Manila became the capital of the Spanish East Indies, with trade soon beginning via the Manila-Acapulco Galleons. The Manila-Acapulco trade route shipped products such as silk, spices, silver, porcelain and gold to the Americas from Asia.[14][15] The first census in the Philippines was founded in 1591, based on tributes collected. The tributes count the total founding population of Spanish-Philippines as 667,612 people,[16] of which: 20,000 were Chinese migrant traders,[17] at different times: around 16,500 individuals were Latino soldier-colonists who were cumulatively sent from Peru and Mexico and they were shipped to the Philippines annually,[18] 3,000 were Japanese residents,[19] and 600 were pure Spaniards from Europe,[20] there was also a large but unknown number of Indian Filipinos, the rest of the population were Malays and Negritos. Thus, with merely 667,612 people, during this era, the Philippines was among the most sparsely populated lands in Asia.

Despite the sparsity of the Philippine population, it was profitable for Mexico City which used it as a transhipment point of cheap Asian products like Silk and Porcelain. However, due to the higher quantity of products from Asia it became a point of contention with the mercantilist policies of mainland Spain which supported manufacturing based on the capital instead of the colonies, in which case the Manila-Mexico commercial alliance was at odds against Madrid.[21][22] The importance of the Philippines to the Spanish empire can be seen by its creation as a separate Captaincy-General.[23] Products brought from Asia were sent to Acapulco then overland to Veracruz, and then shipped to Spain aboard the West Indies Fleets. Later they were traded across Europe. Several cities and towns in the Philippines were founded as Presidios commanded by Spanish officers and staffed by Mexican and Peruvian soldiers who were mostly forcefully conscripted vagrants, estranged teenagers, petty criminals, rebels or political exiles at Mexico and Peru and were thus a rebellious element among the Spanish colonial apparatus in the Philippines.[24]

Since the Philippines was at the center of a crescent from Japan to Indonesia, it alternated into periods of extreme wealth congregating to the location,[25] to periods where it was the arena of constant warfare waged between it and the surrounding nation(s).[26] This left only the fittest and strongest to survive and serve out their military service. There was thus high desertion and death rates which also applied to the native Filipino warriors and laborers levied by Spain, to fight in battles all across the archipelago and elsewhere or build galleons and public works. The repeated wars, lack of wages, dislocation, and near starvation were so intense, that almost half of the soldiers sent from Latin America and the warriors and laborers recruited locally either died or disbanded to the lawless countryside to live as vagabonds among the rebellious natives, escaped enslaved Indians (from India)[27] and Negrito nomads, where they race-mixed through rape or prostitution, which increased the number of Filipinos of Spanish or Latin American descent, but were not the children of valid marriages.[28] This further blurred the racial caste system Spain tried so hard to maintain in the towns and cities.[29] These circumstances contributed to the increasing difficulty of governing the Philippines. Due to these, the Royal Fiscal of Manila wrote a letter to King Charles III of Spain, in which he advises to abandon the colony, but this was successfully opposed by the religious and missionary orders that argued that the Philippines was a launching pad for further conversions in the Far East.[30] Due to the missionary nature of the Philippine colony, unlike in Mexico where most immigrants were of a civilian nature, most settlers in the Philippines were either soldiers, merchants or clergy and were overwhelmingly male.

At times, non-profitable war-torn Philippine colony survived on an annual subsidy paid by the Spanish Crown and often procured from taxes and profits accumulated by the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico), mainly paid by annually sending 75 tons of precious Silver Bullion,[31] gathered from and mined from Potosi, Bolivia where hundreds of thousands of Incan lives were regularly lost while being enslaved to the Mit'a system.[32] Unfortunately, the silver mined through the cost of many lives and being a precious metal barely made it to the starving or dying Spanish, Mexican, Peruvian and Filipino soldiers who were stationed in presidios across the archipelago, struggling against constant invasions, while it was sought after by Chinese, Indian, Arab and Malay merchants in Manila who traded with the Latinos for their precious metal in exchange for silk, spices, pearls and aromatics. Trade and immigration was not just aimed towards the Philippines, however. It also went the opposite direction, to the Americas, from rebellious Filipinos, especially the exiled Filipino royalties, who were denied their traditional rights by new Spanish officers from Spain who replaced the original Spanish conquistadors from Mexico who were more political in alliance-making and who they had treaties of friendship with (due to their common hatred against Muslims, since native Pagan Filipinos fought against the Brunei Sultanate and native Spaniards conquered the Emirate of Granada).[clarification needed] The idealistic original pioneers died and were replaced by ignorant royal officers who broke treaties, thus causing the Conspiracy of the Maharlikas among Filipinos, who conspired together with Bruneians and Japanese, yet the failure of the conspiracy caused the royals' exile to the Americas, where they formed communities across the western coasts, chief among which was Guerrero, Mexico,[33] which was later a center of the Mexican war of Independence.[34]

Spanish ocean trade routes and defense

[edit]

The Spanish crown created a system of convoys of ships (called the flota) to prevent attacks by European privateers. Some isolated attacks on these shipments took place in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea by English and Dutch pirates and privateers. One such act of piracy was led by Francis Drake in 1580, and another by Thomas Cavendish in 1587. In one episode, the cities of Huatulco (Oaxaca) and Barra de Navidad in Jalisco Province of México were sacked. However, these maritime routes, both across the Pacific and the Atlantic, were successful in the defensive and logistical role they played in the history of the Spanish Empire. For over three centuries the Spanish Navy escorted the galleon convoys that sailed around the world. Don Lope Díez de Armendáriz, born in Quito, Ecuador, was the first Viceroy of New Spain who was born in the 'New World'. He formed the 'Navy of Barlovento' (Armada de Barlovento), based in Veracruz, to patrol coastal regions and protect the harbors, port towns, and trade ships from pirates and privateers.

Indigenous revolts

[edit]

After the invasion of central Mexico, there were many major Native American rebellions defeating, changing or challenging Spanish rule. In the Mixtón war in 1541, the viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza led an army against an uprising by Caxcanes. In the 1680 Pueblo revolt, Indians in 24 settlements in New Mexico expelled the Spanish, who left for Texas, an exile lasting a decade. The Chichimeca war lasted over fifty years, 1550–1606, between the Spanish and various indigenous groups of northern New Spain, particularly in silver mining regions and the transportation trunk lines.[35]

Non-sedentary or semi-sedentary Northern Indians were difficult to control once they acquired the mobility of the horse.[36] In 1616, the Tepehuan revolted against the Spanish, but it was relatively quickly suppressed.[37] The Tarahumara Indians were in revolt in the mountains of Chihuahua for several years. In 1670 Chichimecas invaded Durango, and the governor, Francisco González, abandoned its defense. The Spanish-Chamorro Wars that began on Guam in 1670 after the Spanish establishment of a physical presence resulted in a series of sieges of the Spanish presidio, the last in 1684.

In the southern area of New Spain, the Tzeltal Maya and other indigenous groups, including the Tzotzil and Chol revolted in 1712. It was a multiethnic revolt sparked by religious issues in several communities.[38] In 1704 viceroy Francisco Fernández de la Cueva suppressed a rebellion of Pima in Nueva Vizcaya.

Bourbon reforms

[edit]

The Bourbon monarchy embarked upon a far-reaching program to revitalize the economy of its territories, both on the peninsula and its overseas possessions. The crown sought to enhance its control and administrative efficiency, and to decrease the power and privilege of the Roman Catholic Church vis-a-vis the state.[39][40]

The British capture and occupation of both Manila and Havana in 1762, during the global conflict of the Seven Years' War, meant that the Spanish crown had to rethink its military strategy for defending its possessions. The Spanish crown had engaged with Britain for a number of years in low-intensity warfare, with ports and trade routes harassed by English privateers. The crown strengthened the defenses of Veracruz and San Juan de Ulúa, Jamaica, Cuba, and Florida, but the British sacked ports in the late seventeenth century. Santiago de Cuba (1662), St. Augustine Spanish Florida (1665) and Campeche 1678 and so with the loss of Havana and Manila, Spain realized it needed to take significant steps. The Bourbons created a standing army in New Spain, beginning in 1764, and strengthened defensive infrastructure, such as forts.[41][42]

The crown sought reliable information about New Spain and dispatched José de Gálvez as Visitador General (inspector general), who observed conditions needing reform, starting in 1765, in order to strengthen crown control over the kingdom.[43]

An important feature of the Bourbon Reforms was that they ended the significant amount of local control that was a characteristic of the bureaucracy under the Habsburgs, especially through the sale of offices. The Bourbons sought a return to the monarchical ideal of having those not directly connected with local elites as administrators, who in theory should be disinterested, staff the higher echelons of regional government. In practice this meant that there was a concerted effort to appoint mostly peninsulares, usually military men with long records of service, as opposed to the Habsburg preference for prelates, who were willing to move around the global empire. The intendancies were one new office that could be staffed with peninsulares, but throughout the 18th century significant gains were made in the numbers of governors-captain generals, audiencia judges and bishops, in addition to other posts, who were Spanish-born.

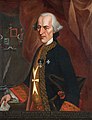

In 1766, the crown appointed Carlos Francisco de Croix, marqués de Croix as viceroy of New Spain. One of his early tasks was to implement the crown's decision to expel the Jesuits from all its territories, accomplished in 1767. Since the Jesuits had significant power, owning large, well managed haciendas, educating New Spain's elite young men, and as a religious order resistant to crown control, the Jesuits were a major target for the assertion of crown control. Croix closed the religious autos-de-fe of the Holy Office of the Inquisition to public viewing, signaling a shift in the crown's attitude toward religion.

Other significant accomplishments under Croix's administration was the founding of the College of Surgery in 1768, part of the crown's push to introduce institutional reforms that regulated professions. The crown was also interested in generating more income for its coffers and Croix instituted the royal lottery in 1769. Croix also initiated improvements in the capital and seat of the viceroyalty, increasing the size of its central park, the Alameda.

Another activist viceroy carrying out reforms was Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursúa, marqués de Valleheroso y conde de Jerena, who served from 1771 to 1779, and died in office. José de Gálvez, now Minister of the Indies following his appointment as Visitor General of New Spain, briefed the newly appointed viceroy about reforms to be implemented. In 1776, a new northern territorial division was established, Commandancy General of the Provincias Internas known as the Provincias Internas (Commandancy General of the Internal Provinces of the North, Spanish: Comandancia y Capitanía General de las Provincias Internas).[44]

Teodoro de Croix, nephew of the former viceroy, was appointed the first Commander General of the Provincias Internas, independent of the Viceroy of New Spain, to provide better administration for the northern frontier provinces. They included Nueva Vizcaya, Nuevo Santander, Sonora y Sinaloa, Las Californias, Coahuila y Tejas (Coahuila and Texas), and Nuevo México. Bucareli was opposed to Gálvez's plan to implement the new administrative organization of intendancies, which he believed would burden areas with sparse population with excessive costs for the new bureaucracy.[45]

The new Bourbon kings did not split the Viceroyalty of New Spain into smaller administrative units as they did with the Viceroyalty of Peru, carving out the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata and the Viceroyalty of New Granada, but New Spain was reorganized administratively and elite American-born Spanish men were passed over for high office. The crown also established a standing military, with the aim of defending its overseas territories.

The Spanish Bourbons monarchs' prime innovation introduction of intendancies, an institution emulating that of Bourbon france. They were first introduced on a large scale in New Spain, by the Minister of the Indies José de Gálvez, in the 1770s, who originally envisioned that they would replace the viceregal system (viceroyalty) altogether. With broad powers over tax collection and the public treasury and with a mandate to help foster economic growth over their districts, intendants encroached on the traditional powers of viceroys, governors and local officials, such as the corregidores, which were phased out as intendancies were established. The Crown saw the intendants as a check on these other officers.

Over time accommodations were made. For example, after a period of experimentation in which an independent intendant was assigned to Mexico City, the office was thereafter given to the same person who simultaneously held the post of viceroy. Nevertheless, the creation of scores of autonomous intendancies throughout the Viceroyalty, created a great deal of decentralization, and in the Captaincy General of Guatemala, in particular, the intendancy laid the groundwork for the future independent nations of the 19th century. In 1780, Minister of the Indies José de Gálvez sent a royal dispatch to Teodoro de Croix, Commandant General of the Internal Provinces of New Spain (Provincias Internas), asking all subjects to donate money to help the American Revolution. Millions of pesos were given.

The focus on the economy (and the revenues it provided to the royal coffers) was also extended to society at large. Economic associations were promoted, such as the Economic Society of Friends of the Country. Similar "Friends of the Country" economic societies were established throughout the Spanish world, including Cuba and Guatemala.[46]

The crown sent a series of scientific expeditions to its overseas possessions, including the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Spain, led by Martín de Sessé and José Mariano Mociño (1787–1808).[47] Alexander von Humboldt spent a year in New Spain in 1804 on his self-funded scientific expedition to Spanish America. Trained as a mining engineer, Humboldt's observations of silver mining in New Spain were especially important to the crown, which depended on New World silver revenues.

The Bourbon Reforms were not a unified or entirely coherent program, but instead a series of crown initiatives designed to revitalize the economies of its overseas possessions and make administration more efficient and firmly under control of the crown. Record keeping improved and records were more centralized. The bureaucracy was staffed with well-qualified men, most of them peninsular-born Spaniards. The preference for them meant that there was resentment from American-born elite men and their families, who were excluded from holding office. The creation of a military meant that some American Spaniards became officers in local militias, but the ranks were filled with poor, mixed-race men, who resented service and avoided it if possible.[48]

18th-century military conflicts

[edit]

The first century that saw the Bourbons on the Spanish throne coincided with series of global conflicts that pitted primarily france against Great Britain. Spain, as an ally of Bourbon france, was drawn into these conflicts. In fact part of the motivation for the Bourbon Reforms was the perceived need to prepare the empire administratively, economically, and militarily for what was the next expected war. The Seven Years' War proved to be catalyst for most of the reforms in the overseas possessions, just like the War of the Spanish Succession had been for the reforms on the Peninsula.

In 1720, the Villasur expedition from Santa Fe met and attempted to parley with French- allied Pawnee in what is now Nebraska. Negotiations were unsuccessful, and a battle ensued; the Spanish were badly defeated, with only thirteen managing to return to New Mexico. Although this was a small engagement, it is significant in that it was the deepest penetration of the Spanish into the Great Plains, establishing the limit to Spanish expansion and influence there.

The War of Jenkins' Ear broke out in 1739 between the Spanish and British and was confined to the Caribbean and Georgia. The major action in the War of Jenkins' Ear was a major amphibious attack launched by the British under Admiral Edward Vernon in March 1741 against Cartagena de Indias, one of Spain's major gold-trading ports in the Caribbean (today Colombia). Although this episode is largely forgotten, it ended in a decisive victory for Spain, who managed to prolong its control of the Caribbean and indeed secure the Spanish Main until the 19th century.

Following the French and Indian War/Seven Years' War, the British troops invaded and captured the Spanish cities of Havana in Cuba and Manila in the Philippines in 1762. The Treaty of Paris (1763) gave Spain control over the Louisiana part of New France including New Orleans, creating a Spanish empire that stretched from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean; but Spain also ceded Florida to Great Britain in order to regain Cuba, which the British occupied during the war. Louisiana settlers, hoping to restore the territory to france, in the bloodless Rebellion of 1768 forced the Louisiana Governor Antonio de Ulloa to flee to Spain. The rebellion was crushed in 1769 by the next governor Alejandro O'Reilly, who executed five of the conspirators. The Louisiana territory was to be administered by superiors in Cuba with a governor on site in New Orleans.

The 21 northern missions in present-day California (U.S.) were established along California's El Camino Real from 1769. In an effort to exclude Britain and Russia from the eastern Pacific, King Charles III of Spain sent forth from Mexico a number of expeditions to the Pacific Northwest between 1774 and 1793. Spain's long-held claims and navigation rights were strengthened and a settlement and fort were built in Nootka Sound, Alaska.

Spain entered the American Revolutionary War as an ally of the United States and France in June 1779. From September 1779 to May 1781, Bernardo de Galvez led an army in a campaign along the Gulf Coast against the British. Galvez's army consisted of Spanish regulars from throughout Latin America and a militia which consisted of mostly Acadians along with Creoles, Germans, and Native Americans. Galvez's army engaged and defeated the British in battles fought at Manchac and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Natchez, Mississippi, Mobile, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida.

The loss of Mobile and Pensacola left the British with no bases along the Gulf Coast. In 1782, forces under Galvez's overall command captured the British naval base at Nassau on New Providence Island in the Bahamas. Galvez was angry that the operation had proceeded against his orders to cancel, and ordered the arrest and imprisonment of Francisco de Miranda, aide-de-camp of Juan Manuel Cajigal, the commander of the expedition. Miranda later ascribed this action on the part of Galvez to jealousy of Cajigal's success.

In the second Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the American Revolution, Great Britain returned control of Florida back to Spain in exchange for the Bahamas. Spain then had control over the Mississippi River south of 32°30' north latitude, and, in what is known as the Spanish Conspiracy, hoped to gain greater control of Louisiana and all of the west. These hopes ended when Spain was pressured into signing Pinckney's Treaty in 1795. France re-acquired Louisiana from Spain in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800. The United States bought the territory from France in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

New Spain claimed the entire west coast of North America and therefore considered the Russian fur trading activity in Alaska, which began in the middle to late 18th century, an encroachment and threat. Likewise, the exploration of the northwest coast by Captain James Cook of the British Navy and the subsequent fur trading activities by British ships was considered an encroachment on Spanish territory. To protect and strengthen its claim, New Spain sent a number of expeditions to the Pacific Northwest between 1774 and 1793.

In 1789, a naval outpost called Santa Cruz de Nuca (or just Nuca) was established at Friendly Cove in Nootka Sound (now Yuquot), Vancouver Island. It was protected by an artillery land battery called Fort San Miguel. Santa Cruz de Nuca was the northernmost establishment of New Spain. It was the first European colony in what is now the province of British Columbia and the only Spanish settlement in what is now Canada. Santa Cruz de Nuca remained under the control of New Spain until 1795, when it was abandoned under the terms of the third Nootka Convention.

Another outpost, intended to replace Santa Cruz de Nuca, was partially built at Neah Bay on the southern side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca in what is now the U.S. state of Washington. Neah Bay was known as Bahía de Núñez Gaona in New Spain, and the outpost there was referred to as "Fuca." It was abandoned, partially finished, in 1792. Its personnel, livestock, cannons, and ammunition were transferred to Nuca.[49]

In 1789, at Santa Cruz de Nuca, a conflict occurred between the Spanish naval officer Esteban José Martínez and the British merchant James Colnett, triggering the Nootka Crisis, which grew into an international incident and the threat of war between Britain and Spain. The first Nootka Convention averted the war but left many specific issues unresolved. Both sides sought to define a northern boundary for New Spain.

At Nootka Sound, the diplomatic representative of New Spain, Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, proposed a boundary at the Strait of Juan de Fuca, but the British representative, George Vancouver refused to accept any boundary north of San Francisco. No agreement could be reached and the northern boundary of New Spain remained unspecified until the Adams–Onís Treaty with the United States (1819). That treaty also ceded Spanish Florida to the United States.

End of the Viceroyalty (1806–1821)

[edit]

The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso ceded to France the vast territory that Napoleon then sold to the United States in 1803, known as the Louisiana Purchase. The United States obtained Spanish Florida in 1819 in the Adams–Onís Treaty. That treaty also defined a northern border for New Spain, at 42° north latitude (now the northern boundary of the U.S. states of California, Nevada, and Utah).

In the 1821 Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire, both Mexico and Central America declared their independence after three centuries of Spanish rule and formed the First Mexican Empire, although Central America quickly rejected the union. After priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla's 1810 Grito de Dolores (call for independence), the insurgent army began an eleven-year war. At first, the Criollo class fought against the rebels. In 1820, a military coup in Spain forced Ferdinand VII to accept the authority of the liberal Spanish Constitution. The specter of liberalism that could undermine the authority and autonomy of the Roman Catholic Church made the Church hierarchy in New Spain view independence in a different light. In an independent nation, the Church anticipated retaining its power. Royalist military officer Agustín de Iturbide proposed uniting with the insurgents with whom he had battled, and gained the alliance of Vicente Guerrero, leader of the insurgents in a region now bearing his name, a region that was populated by immigrants from Africa and the Philippines,[50][51] crucial among which was the Filipino-Mexican General Isidoro Montes de Oca who impressed Criollo Royalist Itubide into joining forces with Vicente Guerrero by Isidoro Montes De Oca defeating royalist forces three times larger than his, in the name of his leader, Vicente Guerrero.[52] Royal government collapsed in New Spain and the Army of the Three Guarantees marched triumphantly into Mexico City in 1821.

The new Mexican Empire offered the crown to Ferdinand VII or to a member of the Spanish royal family that he would designate. After the refusal of the Spanish monarchy to recognize the independence of Mexico, the ejército Trigarante (Army of the Three Guarantees), led by Agustín de Iturbide and Vicente Guerrero, cut all political and economic ties with Spain and crowned Iturbide as emperor Agustín of Mexico. Central America was originally envisioned as part of the Mexican Empire; but it seceded peacefully in 1823, forming the United Provinces of Central America under the Constitution of 1824.

This left only Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Spanish West Indies, and the Philippines in the Spanish East Indies as part of the Spanish Empire; until their loss to the United States in the Spanish–American War (1898). Before, the Spanish-American War, the Philippines had an almost successful revolt against Spain under the uprising of Andres Novales which were supported by Criollos and Latin Americans who were the Philippines, mainly by the former Latino officers "americanos", composed mostly of Mexicans with a sprinkling of Creoles and Mestizos from the now independent nations of Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Chile, Argentina and Costa Rica.[53] went out to start a revolt.[54][55] In the aftermath, Spain, in order to ensure obedience to the empire, disconnected the Philippines from her Latin-American allies and placed in the Spanish army of the colony, Peninsulars from the mainland, which displaced and angered the Latin American and Filipino soldiers who were at the Philippines.[56]

The legacy of the colonial era Mexico is significant in many domains. Mexico was the location of the first printing shop (1539),[57] first university (1551),[58] first public park (1592),[59] and first public library (1640) in the Americas,[60] among other institutions. Important artists of the colonial period, include the writers Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, and Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, painters Cristóbal de Villalpando and Miguel Cabrera, and architect Manuel Tolsá. The Academy of San Carlos (1781) was the first major school and museum of art in the Americas.[61]

German scientist Alexander von Humboldt spent a year in Mexico, finding the scientific community in the capital active and learned. He met Mexican scientist Andrés Manuel del Río Fernández, who discovered the element vanadium in 1801.[62] Many Mexican cultural features including tequila,[63] first distilled in the 16th century, charreria (17th),[64] mariachi (18th) and Mexican cuisine, a fusion of American and European (particularly Spanish) cuisine, arose during the colonial era.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Spanish called their overseas empire "the Indies" until the end of its empire, a remnant of Columbus's assertion that he had reached the Far East, rather than a New World.

References

[edit]- ^ Lockhart & Schwartz (1983), pp. 61–85

- ^ Howard F. Cline, "The Relaciones Geográficas of the Spanish Indies, 1577–1586." Hispanic American Historical Review 44, (1964) 341–374.

- ^ Howard F. Cline, "A Census of the Relaciones Geográficas, 1579–1612." Handbook of Middle American Indians, vol. 12: 324–69. Austin: University of Texas Press 1972.

- ^ "The Relaciónes Geográficas of the Spanish Indies, 1577–1648." Handbook of Middle American Indians, vol. 12: 183–242. Austin: University of Texas Press 1972.

- ^ Howard F. Cline, "The Relaciones Geográficas of Spain, New Spain, and the Spanish Indies: An Annotated Bibliography." Handbook of Middle American Indians vol. 12, 370–95. Austin: University of Texas Press 1972.

- ^ Barbara E. Mundy, The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1996.

- ^ Daniela Bleichmar, Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Spanish Enlightenment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2012, p.32.

- ^ Lockhart & Schwartz (1983), pp. 61–71

- ^ Lockhart & Schwartz (1983), p. 86, map. 4

- ^ Lockhart & Schwartz (1983), p. 86, map. 4

- ^ Lockhart & Schwartz (1983), pp. 86–92

- ^ Altman, Cline & Pescador (2003), pp. 65–66

- ^ Rene Javellana, S. J.Fortress of Empire(1997)

- ^ William Schurz, The Manila Galleon. New York 1939.

- ^ Manuel Carrera Stampa, "La Nao de la China", Historia Mexicana 9, no. 33 (1959), 97–118.

- ^ The Unlucky Country: The Republic of the Philippines in the 21St Century By Duncan Alexander McKenzie (page xii)

- ^ Carol R. Ember; Melvin Ember; Ian A. Skoggard, eds. (2005). History. Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures around the World, Volume 1. Springer.

- ^ Stephanie Mawson, ‘Between Loyalty and Disobedience: The Limits of Spanish Domination in the Seventeenth Century Pacific' (Univ. of Sydney M.Phil. thesis, 2014), appendix 3.

- ^ "Paco". Philippines: Pagenation.com. Archived from the original on May 7, 2010.

- ^ Garcia-Abasalo, Antonio. Spanish Settlers in the Philippines (1571–1599) (PDF). Universidad de Córdoba (Thesis). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 16, 2023.

- ^ Katharine Bjork, "The Link that Kept the Philippines Spanish: Mexican Merchant Interests and the Manila Trade, 1571–1815", Journal of World History 9, no. 1 (1998), 25–50.

- ^ Shirley Fish, Manila-Acapulco Galleons: The Treasure Ships of the Pacific with an Annotated list of Transpacific Galleons, 1565–1815. Central Milton Keynes: Author House 2011.

- ^ Haring (1947), p. 79

- ^ "In Governor Anda y Salazar's opinion, an important part of the problem of vagrancy was the fact that Mexicans and Spanish disbanded after finishing their military or prison terms "all over the islands, even the most distant, looking for subsistence."" ~CSIC riel 208 leg.14

- ^ Iaccarino, Ubaldo (October 2017). ""The Center of a Circle": Manila's Trade with East and Southeast Asia at the Turn of the Sixteenth Century" (PDF). Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 16: 99–120. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020 – via Ostasien Verlag.

- ^ The Early Spanish Period. Dolan 1991

- ^ The Diversity and Reach of the Manila Slave Market Page 36

- ^ "The descendants of Mexican mestizos and native Filipinos were numerous but unaccounted for because they were mostly the result of informal liaisons." ~Garcia de los Arcos, Forzados, 238

- ^ Tomás de Comyn, general manager of the Compañia Real de Filipinas, in 1810 estimated that out of a total population of 2,515,406, "the European Spaniards, and Spanish creoles and mestizos do not exceed 4,000 persons of both sexes and all ages, and the distinct castes or modifications known in America under the name of mulatto, quarteroons, etc., although found in the Philippine Islands, are generally confounded in the three classes of pure Indians, Chinese mestizos and Chinese." In other words, the Mexicans who had arrived in the previous century had so intermingled with the local population that distinctions of origin had been forgotten by the 19th century. The Mexicans who came with Legázpi and aboard succeeding vessels had blended with the local residents so well that their country of origin had been erased from memory.

- ^ Blair, E., Robertson, J., & Bourne, E. (1903). The Philippine islands, 1493–1803 : explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the Catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century. Cleveland, Ohio.

- ^ Bonialian, 2012[citation not found]

- ^ Cole, Jeffrey A. (1985). The Potosí mita, 1573–1700 : compulsory Indian labor in the Andes. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0804712569.

- ^ Mercene, Floro L. Manila Men in the New World: Filipino Migration to Mexico and the Americas from the Sixteenth Century. Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Press, 2007

- ^ "Estado de Guerrero Historia" [State of Guerrero History]. Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. 2005. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ^ Philip Wayne Powell, Soldiers, Indians, and Silver: The Northward Advance of New Spain, 1550–1600. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1952.

- ^ Ida Altman, Sarah Cline, and Javier Pescador, The Early History of Greater Mexico. Prentice Hall 2003, 251.

- ^ Charlotte M. Gradie, The Tepehuan Revolt of 1616: Militarism, Evangelism, and Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century Nueva Vizcaya. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 2000.

- ^ Victoria Reifler Bricker, The Indian Christ, the Indian King: The Historical Substrate of Maya Myth and Ritual. Austin: University of Texas Press 1981.

- ^ N.M. Farriss, Crown and Clergy in Colonial Mexico, 1759–1821: The Crisis of Ecclesiastical Privilege. London: Athlone 1968.

- ^ Lloyd Mecham, Church and State in Latin America: A History of Politicoecclesiastical Relations. Revised edition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 1966.

- ^ Christon Archer, The Army in Bourbon Mexico, 1760–1810. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1977.

- ^ Lyle N. McAlister, The Fuero Militar in New Spain, 1764–1800. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1957.

- ^ Susan Deans-Smith, "Bourbon Reforms" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 153.

- ^ Christon I. Archer, "Antonio María Bucareli y Ursúa" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 164.

- ^ Christon I. Archer, "Antonio María Bucareli y Ursúa" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 164.

- ^ Shafer (1958)

- ^ Daniela Bleichmar, Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2012, pp. 70–72.

- ^ Ida Altman et al., The Early History of Greater Mexico. Prentice Hall 2003, pp. 316–17.

- ^ Tovell (2008), pp. 218–219

- ^ Wade, Lizzie (12 April 2018). "Latin America's lost histories revealed in modern DNA". Science Magazine.

- ^ Mercene, Floro L. "Filipinos in Mexican History". The Manila Bulletin Online. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007.

- ^ Guevarra, Rudy P. Jr. (10 November 2011). "Filipinos in Nueva España: Filipino-Mexican Relations, Mestizaje, and Identity in Colonial and Contemporary Mexico". Journal of Asian American Studies. 14 (3): 389–416. doi:10.1353/jaas.2011.0029. S2CID 144426711.

(Page 414; Citation 56: 'According to Ricardo Pinzon, these two Filipino soldiers—Francisco Mongoy and Isidoro Montes de Oca—were so distinguished in battle that they are regarded as folk heroes in Mexico. General Vicente Guerrero later became the first president of Mexico of African descent.' See Floro L. Mercene, "Central America: Filipinos in Mexican History", (Ezilon Infobase, January 28, 2005)

- ^ Quirino, Carlos. "Filipinos In Mexico's History 4 (The Mexican Connection – The Cultural Cargo Of The Manila-Acapulco Galleons)". Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020 – via adoborepublic.net.

- ^ John Scott, John Taylor (1826). The London Magazine, Volume 14. pp. 512–516.

- ^ Duka, Cecilio D. (2008). Struggle for Freedom 2008 Edition. Rex Bookstore. p. 106. ISBN 9789712350450.

- ^ Officers in the army of the Philippines were almost totally composed of Americans,” observed the Spanish historian José Montero y Vidal. “They received in great disgust the arrival of peninsular officers as reinforcements, partly because they supposed they would be shoved aside in the promotions and partly because of racial antagonisms.”

- ^ "First Printing Press in the Americas was Established in Mexico". Latino Book Review. 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ "UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO IS THE OLDEST UNIVERSITY IN NORTH AMERICA". Vallarta Daily News. 15 September 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ "Mexico City's Alameda Central: the inspiration behind NYC's Central Park?". City Express blog. 15 September 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ "Oldest Public Library in the Americas is in Mexico". Latino Book Review. 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ "Academy of San Carlos". Mexico es Cultura. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ "Vanadium Element Facts". Chemicool Periodic Table. 18 October 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ Archibald, Anna (27 July 2015). "Everything You Need to Know About the History of Tequila". Liquor.com. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ Galvez, Francisco (27 June 2017). "A brief History of Charreria". Charro Azteca. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

Sources

[edit]- Altman, Ida; Cline, Sarah; Pescador, Juan Javier (2003). The Early History of Greater Mexico. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-1309-1543-6.

- Haring, Clarence Henry (1947). The Spanish Empire in America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Lockhart, James; Schwartz, Stuart (1983). Early Latin America. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Shafer, Robert J. (1958). The Economic Societies in the Spanish World, 1763-1821. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

- Tovell, Freeman M. (2008). At the Far Reaches of Empire: the Life of Juan Francisco De La Bodega Y Quadra. University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-1367-9.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch