History of philosophy

The history of philosophy is the systematic study of the development of philosophical thought. It focuses on philosophy as rational inquiry based on argumentation, but some theorists also include myth, religious traditions, and proverbial lore.

Western philosophy originated with an inquiry into the fundamental nature of the cosmos in Ancient Greece. Subsequent philosophical developments covered a wide range of topics including the nature of reality and the mind, how people should act, and how to arrive at knowledge. The medieval period was focused more on theology. The Renaissance period saw a renewed interest in Ancient Greek philosophy and the emergence of humanism. The modern period was characterized by an increased focus on how philosophical and scientific knowledge is created. Its new ideas were used during the Enlightenment period to challenge traditional authorities. Influential developments in the 19th and 20th centuries included German idealism, pragmatism, positivism, formal logic, linguistic analysis, phenomenology, existentialism, and postmodernism.

Arabic–Persian philosophy was strongly influenced by Ancient Greek philosophers. It had its peak period during the Islamic Golden Age. One of its key topics was the relation between reason and revelation as two compatible ways of arriving at the truth. Avicenna developed a comprehensive philosophical system that synthesized Islamic faith and Greek philosophy. After the Islamic Golden Age, the influence of philosophical inquiry waned, partly due to Al-Ghazali's critique of philosophy. In the 17th century, Mulla Sadra developed a metaphysical system based on mysticism. Islamic modernism emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries as an attempt to reconcile traditional Islamic doctrines with modernity.

Indian philosophy is characterized by its combined interest in the nature of reality, the ways of arriving at knowledge, and the spiritual question of how to reach enlightenment. Its roots are in the religious scriptures known as the Vedas. Subsequent Indian philosophy is often divided into orthodox schools, which are closely associated with the teachings of the Vedas, and heterodox schools, like Buddhism and Jainism. Influential schools based on them include the Hindu schools of Advaita Vedanta and Navya-Nyāya as well as the Buddhist schools of Madhyamaka and Yogācāra. In the modern period, the exchange between Indian and Western thought led various Indian philosophers to develop comprehensive systems. They aimed to unite and harmonize diverse philosophical and religious schools of thought.

Central topics in Chinese philosophy were right social conduct, government, and self-cultivation. In early Chinese philosophy, Confucianism explored moral virtues and how they lead to harmony in society while Daoism focused on the relation between humans and nature. Later developments include the introduction and transformation of Buddhist teachings and the emergence of the schools of Xuanxue and Neo-Confucianism. The modern period in Chinese philosophy was characterized by its encounter with Western philosophy, specifically with Marxism. Other influential traditions in the history of philosophy were Japanese philosophy, Latin American philosophy, and African philosophy.

Definition and related disciplines

[edit]The history of philosophy is the field of inquiry that studies the historical development of philosophical thought. It aims to provide a systematic and chronological exposition of philosophical concepts and doctrines, as well as the philosophers who conceived them and the schools of thought to which they belong. It is not merely a collection of theories but attempts to show how these theories are interconnected. For example, some schools of thought build on earlier theories, while others reject them and offer alternative explanations.[1] Purely mystical and religious traditions are often excluded from the history of philosophy if their claims are not based on rational inquiry and argumentation. However, some theorists treat the topic broadly, including the philosophical aspects of traditional worldviews, religious myths, and proverbial lore.[2]

The history of philosophy has both a historical and a philosophical component. The historical component is concerned with how philosophical thought has unfolded throughout the ages. It explores which philosophers held particular views and how they were influenced by their social and cultural contexts. The philosophical component, on the other hand, evaluates the studied theories for their truth and validity. It reflects on the arguments presented for these positions and assesses their hidden assumptions, making the philosophical heritage accessible to a contemporary audience while evaluating its continued relevance. Some historians of philosophy focus primarily on the historical component, viewing the history of philosophy as part of the broader discipline of intellectual history. Others emphasize the philosophical component, arguing that the history of philosophy transcends intellectual history because its interest is not exclusively historical.[3] It is controversial to what extent the history of philosophy can be understood as a discipline distinct from philosophy itself. Some theorists contend that the history of philosophy is an integral part of philosophy.[4] For example, Neo-Kantians like Wilhelm Windelband argue that philosophy is essentially historical and that it is not possible to understand a philosophical position without understanding how it emerged.[5]

Closely related to the history of philosophy is the historiography of philosophy, which examines the methods used by historians of philosophy. It is also interested in how dominant opinions in this field have changed over time.[6] Different methods and approaches are used to study the history of philosophy. Some historians focus primarily on philosophical theories, emphasizing their claims and ongoing relevance rather than their historical evolution. Another approach sees the history of philosophy as an evolutionary process, assuming clear progress from one period to the next, with earlier theories being refined or replaced by more advanced later theories. Other historians seek to understand past philosophical theories as products of their time, focusing on the positions accepted by past philosophers and the reasons behind them, often without concern for their relevance today. These historians study how the historical context and the philosopher's biography influenced their philosophical outlook.[7]

Another important methodological feature is the use of periodization, which involves dividing the history of philosophy into distinct periods, each corresponding to one or several philosophical tendencies prevalent during that historical timeframe.[8] Traditionally, the history of philosophy has focused primarily on Western philosophy. However, in a broader sense, it includes many non-Western traditions such as Arabic–Persian philosophy, Indian philosophy, and Chinese philosophy.[9]

Western

[edit]Western philosophy refers to the philosophical traditions and ideas associated with the geographical region and cultural heritage of the Western world. It originated in Ancient Greece and subsequently expanded to the Roman Empire, later spreading to Western Europe and eventually reaching other regions, including North America, Latin America, and Australia. Spanning over 2,500 years, Western philosophy began in the 6th century BCE and continues to evolve today.[10]

Ancient

[edit]Western philosophy originated in Ancient Greece in the 6th century BCE. This period is conventionally considered to have ended in 529 CE when the Platonic Academy and other philosophical schools in Athens were closed by order of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, who sought to suppress non-Christian teachings.[11]

Presocratic

[edit]The first period of Ancient Greek philosophy is known as Presocratic philosophy, which lasted until about the mid-4th century BCE. Studying Presocratic philosophy can be challenging because many of the original texts have only survived in fragments and often have to be reconstructed based on quotations found in later works.[12]

A key innovation of Presocratic philosophy was its attempt to provide rational explanations for the cosmos as a whole. This approach contrasted with the prevailing Greek mythology, which offered theological interpretations—such as the myth of Uranus and Gaia—to emphasize the roles of gods and goddesses who continued to be worshipped even as Greek philosophy evolved. The Presocratic philosophers were among the first to challenge traditional Greek theology, seeking instead to provide empirical theories to explain how the world came into being and why it functions as it does.[13]

Thales (c. 624–545 BCE), often regarded as the first philosopher, sought to describe the cosmos in terms of a first principle, or arche. He identified water as this primal source of all things. Anaximander (c. 610–545 BCE) proposed a more abstract explanation, suggesting that the eternal substance responsible for the world's creation lies beyond human perception. He referred to this arche as the apeiron, meaning "the boundless".[14]

Heraclitus (c. 540–480 BCE) viewed the world as being in a state of constant flux, stating that one cannot step into the same river twice. He also emphasized the role of logos, which he saw as an underlying order governing both the inner self and the external world.[15] In contrast, Parmenides (c. 515–450 BCE) argued that true reality is unchanging, eternal, and indivisible. His student Zeno of Elea (c. 490–430 BCE) formulated several paradoxes to support this idea, asserting that motion and change are illusions, as illustrated by his paradox of Achilles and the Tortoise.[16]

Another significant theory from this period was the atomism of Democritus (c. 460–370 BCE), who posited that reality is composed of indivisible particles called atoms.[17] Other notable Presocratic philosophers include Anaximenes, Pythagoras, Xenophanes, Empedocles, Anaxagoras, Leucippus, and the sophists, such as Protagoras and Gorgias.[18]

Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle

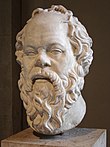

[edit]The philosophy of Socrates (469–399 BCE) and Plato (427–347 BCE) built on Presocratic philosophy but also introduced significant changes in focus and methodology. Socrates did not write anything himself, and his influence is largely due to the impact he made on his contemporaries, particularly through his approach to philosophical inquiry. This method, often conducted in the form of Socratic dialogues, begins with simple questions to explore a topic and critically reflect on underlying ideas and assumptions. Unlike the Presocratics, Socrates was less concerned with metaphysical theories and more focused on moral philosophy. Many of his dialogues explore the question of what it means to lead a good life by examining virtues such as justice, courage, and wisdom. Despite being regarded as a great teacher of ethics, Socrates did not advocate specific moral doctrines. Instead, he aimed to prompt his audience to think for themselves and recognize their own ignorance.[19]

Most of what is known about Socrates comes from the writings of his student Plato. Plato's works are presented in the form of dialogues between various philosophers, making it difficult to determine which ideas are Socrates' and which are Plato's own theories. Plato's theory of forms asserts that the true nature of reality is found in abstract and eternal forms or ideas, such as the forms of beauty, justice, and goodness. The physical and changeable world of the senses, according to Plato, is merely an imperfect copy of these forms. The theory of forms has had a lasting influence on subsequent views of metaphysics and epistemology. Plato is also considered a pioneer in the field of psychology. He divided the soul into three faculties: reason, spirit, and desire, each responsible for different mental phenomena and interacting in various ways. Plato also made contributions to ethics and political philosophy.[20] Additionally, Plato founded the Academy, which is often considered the first institution of higher education.[21]

Aristotle (384–322 BCE), who began as a student at Plato's Academy, became a systematic philosopher whose teachings were transcribed into treatises on various subjects, including the philosophy of nature, metaphysics, logic, and ethics. Aristotle introduced many technical terms in these fields that are still used today. While he accepted Plato's distinction between form and matter, he rejected the idea that forms could exist independently of matter, arguing instead that forms and matter are interdependent. This debate became central to the problem of universals, which was discussed by many subsequent philosophers. In metaphysics, Aristotle presented a set of basic categories of being as a framework for classifying and analyzing different aspects of existence. He also introduced the concept of the four causes to explain why change and movement occur in nature. According to his teleological cause, for example, everything in nature has a purpose or goal toward which it moves. Aristotle's ethical theory emphasizes that leading a good life involves cultivating virtues to achieve eudaimonia, or human flourishing. In logic, Aristotle codified rules for correct inferences, laying the foundation for formal logic that would influence philosophy for centuries.[22]

Hellenistic and Roman

[edit]After Aristotle, ancient philosophy saw the rise of broader philosophical movements, such as Epicureanism, Stoicism, and Skepticism, which are collectively known as the Hellenistic schools of thought. These movements primarily focused on fields like ethics, physics, logic, and epistemology. This period began with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE and had its main influence until the end of the Roman Republic in 31 BCE.[23]

The Epicureans built upon and refined Democritus's idea that nature is composed of indivisible atoms. In ethics, they viewed pleasure as the highest good but rejected the notion that luxury and indulgence in sensory pleasures lead to long-term happiness. Instead, they advocated a nuanced form of hedonism, where a simple life characterized by tranquillity was the best way to achieve happiness.[24]

The Stoics rejected this hedonistic outlook, arguing that desires and aversions are obstacles to living in accordance with reason and virtue. To overcome these desires, they advocated self-mastery and an attitude of indifference.[25]

The skeptics focused on how judgments and opinions impact well-being. They argued that dogmatic beliefs lead to emotional disturbances and recommended that people suspend judgments on matters where certainty is unattainable. Some skeptics went further, claiming that this suspension of judgment should apply to all beliefs, suggesting that any form of knowledge is impossible.[26]

The school of Neoplatonism, which emerged in the later part of the ancient period, began in the 3rd century CE and reached its peak by the 6th century CE. Neoplatonism inherited many ideas from Plato and Aristotle, transforming them in creative ways. Its central doctrine posits a transcendent and ineffable entity responsible for all existence, referred to as "the One" or "the Good." From the One emerges the Intellect, which contemplates the One, and this, in turn, gives rise to the Soul, which generates the material world. Influential Neoplatonists include Plotinus (204–270 CE) and his student Porphyry (234–305 CE).[27]

Medieval

[edit]The medieval period in Western philosophy began between 400 and 500 CE and ended between 1400 and 1500 CE.[28] A key distinction between this period and earlier philosophical traditions was its emphasis on religious thought. The Christian Emperor Justinian ordered the closure of philosophical schools, such as Plato's Academy. As a result, intellectual activity became concentrated within the Church, and diverging from doctrinal orthodoxy was fraught with risks. Due to these developments, some scholars consider this era a "dark age" compared to what preceded and followed it.[29] Central topics during this period included the problem of universals, the nature of God, proofs for the existence of God, and the relationship between reason and faith. The early medieval period was heavily influenced by Plato's philosophy, while Aristotelian ideas became dominant later.[30]

Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) was deeply influenced by Platonism and utilized this perspective to interpret and explain key concepts and problems within Christian doctrine. He embraced the Neoplatonist idea that God, or the ultimate source, is both good and incomprehensible. This led him to address the problem of evil—specifically, how evil could exist in a world created by a benevolent, all-knowing, and all-powerful God. Augustine's explanation centered on the concept of free will, asserting that God granted humans the ability to choose between good and evil, along with the responsibility for those choices. Augustine also made significant contributions in other areas, including arguments for the existence of God, his theory of time, and his just war theory.[31]

Boethius (477–524 CE) had a profound interest in Greek philosophy. He translated many of Aristotle's works and sought to integrate and reconcile them with Christian doctrine. Boethius addressed the problem of universals and developed a theory to harmonize Plato's and Aristotle's views. He proposed that universals exist in the mind without matter in one sense, but also exist within material objects in another sense. This idea influenced subsequent medieval debates on the problem of universals, inspiring nominalists to argue that universals exist only in the mind. Boethius also explored the problem of the trinity, addressing the Christian doctrine of how God can exist as three persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—simultaneously.[32]

Scholasticism

[edit]The later part of the medieval period was dominated by scholasticism, a philosophical method heavily influenced by Aristotelian philosophy and characterized by systematic and methodological inquiry.[33] The intensified interest in Aristotle during this period was largely due to the Arabic–Persian tradition, which preserved, translated, and interpreted many of Aristotle's works that had been lost in the Western world.[34]

Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109 CE) is often regarded as the father of scholasticism. He viewed reason and faith as complementary, each depending on the other for a fuller understanding. Anselm is best known for his ontological argument for the existence of God, where he defined God as the greatest conceivable being and argued that such a being must exist outside of the mind. He posited that if God existed only in the mind, He would not be the greatest conceivable being, since a being that exists in reality is greater than one that exists only in thought.[35] Peter Abelard (1079–1142) similarly emphasized the harmony between reason and faith, asserting that both emerge from the same divine source and therefore cannot be in contradiction. Abelard was also known for his nominalism, which claimed that universals exist only as mental constructs.[36]

Thomas Aquinas (1224–1274 CE) is often considered the most influential medieval philosopher. Rooted in Aristotelianism, Aquinas developed a comprehensive system of scholastic philosophy that encompassed areas such as metaphysics, theology, ethics, and political theory. Many of his insights were compiled in his seminal work, the Summa Theologiae. A key goal in Aquinas's writings was to demonstrate how faith and reason work in harmony. He argued that reason supports and reinforces Christian tenets, but faith in God's revelation is still necessary since reason alone cannot comprehend all truths. This is particularly relevant to claims such as the eternality of the world and the intricate relationship between God and His creation. In metaphysics, Aquinas posited that every entity is characterized by two aspects: essence and existence. Understanding a thing involves grasping its essence, which can be done without perceiving whether it exists. However, in the case of God, Aquinas argued that His existence is identical to His essence, making God unique.[37] In ethics, Aquinas held that moral principles are rooted in human nature. He believed that ethics is about pursuing what is good and that humans, as rational beings, have a natural inclination to pursue the Good.[38] In natural theology, Aquinas's famous Five Ways are five arguments for the existence of God.[39]

Duns Scotus (1266–1308 CE) engaged critically with many of Aquinas's ideas. In metaphysics, Scotus rejected Aquinas's claim of a real distinction between essence and existence. Instead, he argued that this distinction is only formal, meaning essence and existence are two aspects of a thing that cannot be separated. Scotus further posited that each individual entity has a unique essence, known as haecceity, which distinguishes it from other entities of the same kind.[40]

William of Ockham (1285–1347 CE) is one of the last scholastic philosophers. He is known for formulating the methodological principle known as Ockham's Razor, which is used to choose between competing explanations of the same phenomenon. Ockham's Razor states that the simplest explanation, the one that assumes the existence of fewer entities, should be preferred. Ockham employed this principle to argue for nominalism and against realism about universals, contending that nominalism is the simpler explanation since it does not require the assumption of the independent existence of universals.[41]

Renaissance

[edit]The Renaissance period began in the mid-14th century and lasted until the early 17th century. This cultural and intellectual movement originated in Italy and gradually spread to other regions of Western Europe. Key aspects of the Renaissance included a renewed interest in Ancient Greek philosophy and the emergence of humanism, as well as a shift toward scientific inquiry. This represented a significant departure from the medieval period, which had been primarily focused on religious and scholastic traditions. Another notable change was that intellectual activity was no longer as closely tied to the Church as before; most scholars of this period were not clerics.[42]

An important aspect of the resurgence of Ancient Greek philosophy during the Renaissance was a revived enthusiasm for the teachings of Plato. This Renaissance Platonism was still conducted within the framework of Christian theology and often aimed to demonstrate how Plato's philosophy was compatible with and could be applied to Christian doctrines. For example, Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) argued that souls form a connection between the realm of Platonic forms and the sensory realm. According to Plato, love can be understood as a ladder leading to higher forms of understanding. Ficino interpreted this concept in an intellectual sense, viewing it as a way to relate to God through the love of knowledge.[43]

The revival of Ancient Greek philosophy during the Renaissance was not limited to Platonism; it also encompassed other schools of thought, such as Skepticism, Epicureanism, and Stoicism.[44] This revival was closely associated with the rise of Renaissance humanism, a human-centered worldview that highly valued the academic disciplines studying human society and culture. This shift in perspective also involved seeing humans as genuine individuals. Although Renaissance humanism was not primarily a philosophical movement, it brought about many social and cultural changes that affected philosophical activity.[45] These changes were also accompanied by an increased interest in political philosophy. Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) argued that a key responsibility of rulers is to ensure stability and security. He believed they should govern effectively to benefit the state as a whole, even if harsh circumstances require the use of force and ruthless actions. In contrast, Thomas More (1478–1535) envisioned an ideal society characterized by communal ownership, egalitarianism, and devotion to public service.[46]

The Renaissance also witnessed various developments in the philosophy of nature and science, which helped lay the groundwork for the scientific revolution. One such development was the emphasis on empirical observation in scientific inquiry. Another was the idea that mathematical explanations should be employed to understand these observations.[47] Francis Bacon (1561–1626 CE) is often seen as a transitional figure between the Renaissance and modernity. He sought to revolutionize logic and scientific inquiry with his work Novum Organum, which was intended to replace Aristotle's influential treatises on logic. Bacon's work discussed, for example, the role of inductive reasoning in empirical inquiry, which involves deriving general laws from numerous individual observations.[48] Another key transitional figure was Galileo Galilei (1564–1642 CE), who played a crucial role in the Copernican Revolution by asserting that the Sun, rather than the Earth, is at the center of the Solar System. [49]

Early modern

[edit]Early modern philosophy encompasses the 17th and 18th centuries. The philosophers of this period are traditionally divided into empiricists and rationalists. However, contemporary historians argue that this division is not a strict dichotomy but rather a matter of varying degrees. These schools share a common goal of establishing a clear, rigorous, and systematic method of inquiry. This philosophical emphasis on method mirrored the advances occurring simultaneously during the scientific revolution.

Empiricism and rationalism differ concerning the type of method they advocate. Empiricism focuses on sensory experience as the foundation of knowledge. In contrast, rationalism emphasizes reason—particularly the principles of non-contradiction and sufficient reason—and the belief in innate knowledge. While the emphasis on method was already foreshadowed in Renaissance thought, it only came to full prominence during the early modern period.

The second half of this period saw the emergence of the Enlightenment movement, which used these philosophical advances to challenge traditional authorities while promoting progress, individual freedom, and human rights.[50]

Empiricism

[edit]

Empiricism in the early modern period was mainly associated with British philosophy. John Locke (1632–1704) is often considered the father of empiricism. In his book An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, he rejected the notion of innate knowledge and argued that all knowledge is derived from experience. He asserted that the mind is a blank slate at birth, relying entirely on sensory experience to acquire ideas. Locke distinguished between primary qualities, which he believed are inherent in external objects and exist independently of any observer, and secondary qualities, which are the powers of objects to produce sensations in observers.[51]

George Berkeley (1685–1753) was strongly influenced by Locke but proposed a more radical form of empiricism. He developed a form of idealism, giving primacy to perceptions and ideas over material objects. Berkeley argued that objects only exist insofar as they are perceived by the mind, leading to the conclusion that there is no reality independent of perception.[52]

David Hume (1711–1776) also upheld the empiricist principle that knowledge is derived from sensory experience. However, he took this idea further by arguing that it is impossible to know with certainty that one event causes another. Hume's reasoning was that the connection between cause and effect is not directly perceivable. Instead, the mind observes consistent patterns between events and develops a habit of expecting certain outcomes based on prior experiences.[53]

The empiricism promoted by Hume and other philosophers had a significant impact on the development of the scientific method, particularly in its emphasis on observation, experimentation, and rigorous testing.[54]

Rationalism

[edit]

Another dominant school of thought in this period was rationalism. René Descartes (1596–1650) played a pivotal role in its development. He sought to establish absolutely certain knowledge and employed methodological doubt, questioning all his beliefs to find an indubitable foundation for knowledge. He discovered this foundation in the statement "I think, therefore I am." Descartes used various rationalist principles, particularly the focus on deductive reasoning, to build a comprehensive philosophical system upon this foundation. His philosophy is rooted in substance dualism, positing that the mind and body are distinct, independent entities that coexist.[55]

The rationalist philosophy of Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) placed even greater emphasis on deductive reasoning. He developed and employed the so-called geometrical method to construct his philosophical system. This method begins with a small set of self-evident axioms and proceeds to derive a comprehensive philosophical system through deductive reasoning. Unlike Descartes, Spinoza arrived at a metaphysical monism, asserting that there is only one substance in the universe.[56] Another influential rationalist was Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716). His principle of sufficient reason posits that everything has a reason or explanation. Leibniz used this principle to develop his metaphysical system known as monadology.[57]

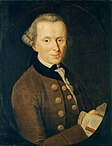

Enlightenment and other late modern philosophy

[edit]The latter half of the modern period saw the emergence of the cultural and intellectual movement known as the Enlightenment. This movement drew on both empiricism and rationalism to challenge traditional authorities and promote the pursuit of knowledge. It advocated for individual freedom and held an optimistic view of progress and the potential for societal improvement.[58] Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) was one of the central thinkers of the Enlightenment. He emphasized the role of reason in understanding the world and used it to critique dogmatism and blind obedience to authority. Kant sought to synthesize both empiricism and rationalism within a comprehensive philosophical system. His transcendental idealism explored how the mind, through its pre-established categories, shapes human experience of reality. In ethics, he developed a deontological moral system based on the categorical imperative, which defines universal moral duties.[59] Other important Enlightenment philosophers included Voltaire (1694–1778), Montesquieu (1689–1755), and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778).[60]

Political philosophy during this period was shaped by Thomas Hobbes's (1588–1679) work, particularly his book Leviathan. Hobbes had a pessimistic view of the natural state of humans, arguing that it involves a war of all against all. According to Hobbes, the purpose of civil society is to avoid this state of chaos. This is achieved through a social contract in which individuals cede some of their rights to a central and immensely powerful authority in exchange for protection from external threats.[61] Jean-Jacques Rousseau also theorized political life using the concept of a social contract, but his political outlook differed significantly due to his more positive assessment of human nature. Rousseau's views led him to advocate for democracy.[62]

19th century

[edit]The 19th century was a rich and diverse period in philosophy, during which the term "philosophy" acquired the distinctive meaning it holds today: a discipline distinct from the empirical sciences and mathematics. A rough division between two types of philosophical approaches in this period can be drawn. Some philosophers, like those associated with German and British idealism, sought to provide comprehensive and all-encompassing systems. In contrast, other thinkers, such as Bentham, Mill, and the American pragmatists, focused on more specific questions related to particular fields, such as ethics and epistemology.[63]

Among the most influential philosophical schools of this period was German idealism, a tradition inaugurated by Immanuel Kant, who argued that the conceptual activity of the subject is always partially constitutive of experience and knowledge. Subsequent German idealists critiqued what they saw as theoretical problems with Kant's dualisms and the contradictory status of the thing-in-itself.[64] They sought a single unifying principle as the foundation of all reality. Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814) identified this principle as the activity of the subject or transcendental ego, which posits both itself and its opposite. Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775–1854) rejected this focus on the ego, instead proposing a more abstract principle, referred to as the absolute or the world-soul, as the foundation of both consciousness and nature.[65]

The philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) is often described as the culmination of this tradition.[66] Hegel reconstructed a philosophical history in which the measure of progress is the actualization of freedom. He applied this not only to political life but also to philosophy, which he claimed aims for self-knowledge characterized by the identity of subject and object. His term for this is "the absolute" because such knowledge—achieved through art, religion, and philosophy—is entirely self-conditioned.[67]

Further influential currents of thought in this period included historicism and neo-Kantianism. Historicists such as Johann Gottfried Herder emphasized the validity and unique nature of historical knowledge of individual events, contrasting this with the universal knowledge of eternal truths. Neo-Kantianism was a diverse philosophical movement that revived and reinterpreted Kant's ideas.[68]

British idealism developed later in the 19th century and was strongly influenced by Hegel. For example, Francis Herbert Bradley (1846–1924) argued that reality is an all-inclusive totality of being, identified with absolute spirit. He is also famous for claiming that external relations do not exist.[69]

Karl Marx (1818–1883) was another philosopher inspired by Hegel's ideas. He applied them to the historical development of society based on class struggle. However, he rejected the idealistic outlook in favor of dialectical materialism, which posits that economics rather than spirit is the basic force behind historical development.[70]

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) proposed that the underlying principle of all reality is the will, which he saw as an irrational and blind force. Influenced by Indian philosophy, he developed a pessimistic outlook, concluding that the expressions of the will ultimately lead to suffering.[71] He had a profound influence on Friedrich Nietzsche, who saw the will to power as a fundamental driving force in nature. Nietzsche used this concept to critique many religious and philosophical ideas, arguing that they were disguised attempts to wield power rather than expressions of pure spiritual achievement.[72]

In the field of ethics, Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) developed the philosophy of utilitarianism. He argued that whether an action is right depends on its utility, i.e., on the pleasure and pain it produces. The goal of actions, according to Bentham, is to maximize happiness or to produce "the greatest good for the greatest number." His student John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) became one of the foremost proponents of utilitarianism, further refining the theory by asserting that what matters is not just the quantity of pleasure and pain, but also their quality.[73]

Toward the end of the 19th century, the philosophy of pragmatism emerged in the United States. Pragmatists evaluate philosophical ideas based on their usefulness and effectiveness in guiding action. Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) is usually considered the founder of pragmatism. He held that the meaning of ideas and theories lies in their practical and observable consequences. For example, to say that an object is hard means that, on a practical level, it is difficult to break, pierce, or scratch. Peirce argued that a true belief is a stable belief that works, even if it must be revised in the future. His pragmatist philosophy gained wider popularity through his lifelong friend William James (1842–1910), who applied Peirce's ideas to psychology. James argued that the meaning of an idea consists of its experiential consequences and rejected the notion that experiences are isolated events, instead proposing the concept of a stream of consciousness.[74]

20th century

[edit]Philosophy in the 20th century is usually divided into two main traditions: analytic philosophy and continental philosophy.[a] Analytic philosophy was dominant in English-speaking countries and emphasized clarity and precise language. It often employed tools like formal logic and linguistic analysis to examine traditional philosophical problems in fields such as metaphysics, epistemology, science, and ethics. Continental philosophy was more prominent in European countries, particularly in Germany and France. It is an umbrella term without a precisely established meaning and covers philosophical movements like phenomenology, hermeneutics, existentialism, deconstruction, critical theory, and psychoanalytic theory.[76]

Interest in academic philosophy increased rapidly in the 20th century, as evidenced by the growing number of philosophical publications and the increasing number of philosophers working at academic institutions.[77] Another change during this period was the increased presence of female philosophers. However, despite this progress, women remained underrepresented in the field.[78]

Some schools of thought in 20th-century philosophy do not clearly fall into either analytic or continental traditions. Pragmatism evolved from its 19th-century roots through scholars like Richard Rorty (1931–2007) and Hilary Putnam (1926–2016). It was applied to new fields of inquiry, such as epistemology, politics, education, and the social sciences.[79]

The 20th century also saw the rise of feminism in philosophy, which studies and critiques traditional assumptions and power structures that disadvantage women. Prominent feminist philosophers include Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986), Martha Nussbaum (1947–present), and Judith Butler (1956–present).[80]

Analytic

[edit]George Edward Moore (1873–1958) was one of the founding figures of analytic philosophy. He emphasized the importance of common sense and used it to argue against radical forms of philosophical skepticism. Moore was particularly influential in the field of ethics, where he claimed that our actions should promote the good. He argued that the concept of "good" cannot be defined in terms of other concepts and that whether something is good can be known through intuition.[81]

Gottlob Frege (1848–1925) was another pioneer of the analytic tradition. His development of modern symbolic logic had a significant impact on subsequent philosophers, even outside the field of logic. Frege employed these advances in his attempt to prove that arithmetic can be reduced to logic, a thesis known as logicism.[82] The logicist project of Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) was even more ambitious since it included not only arithmetic but also geometry and analysis. Although their attempts were very fruitful, they did not fully succeed, as additional axioms beyond those of logic are required. In the philosophy of language, Russell's theory of definite descriptions was influential. It explains how to make sense of paradoxical expressions like "the present King of France," which do not refer to any existing entity.[83] Russell also developed the theory of logical atomism, which was further refined by his student Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951). According to Wittgenstein's early philosophy, as presented in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, the world is made up of a multitude of atomic facts. The world and language have the same logical structure, making it possible to represent these facts using propositions. Despite the influence of this theory, Wittgenstein came to reject it in his later philosophy. He argued instead that language consists of a variety of games, each with its own rules and conventions. According to this view, meaning is determined by usage and not by referring to facts.[84]

Logical positivism developed in parallel to these ideas and was strongly influenced by empiricism. It is primarily associated with the Vienna Circle and focused on logical analysis and empirical verification. One of its prominent members was Rudolf Carnap (1891–1970), who defended the verification principle. This principle claims that a statement is meaningless if it cannot be verified through sensory experience or the laws of logic. Carnap used this principle to reject the discipline of metaphysics in general.[85] However, this principle was later criticized by Carnap's student Willard Van Orman Quine (1908–2000) as one of the dogmas of empiricism. A core idea of Quine's philosophy was naturalism, which he understood as the claim that the natural sciences provide the most reliable framework for understanding the world. He used this outlook to argue that mathematical entities have real existence because they are indispensable to science.[86]

Wittgenstein's later philosophy formed part of ordinary language philosophy, which analyzed everyday language to understand philosophical concepts and problems. The theory of speech acts by John Langshaw Austin (1911–1960) was an influential early contribution to this field. Other prominent figures in this tradition include Gilbert Ryle (1900–1976) and Sir Peter Frederick Strawson (1919–2006). The shift in emphasis on the role of language is known as the linguistic turn.[87]

Richard Mervyn Hare (1919–2002) and John Leslie Mackie (1917–1981) were influential ethical philosophers in the analytic tradition, while John Rawls (1921–2002) and Robert Nozick (1938–2002) made significant contributions to political philosophy.[88]

Continental

[edit]

Phenomenology was an important early movement in the tradition of continental philosophy. It aimed to provide an unprejudiced description of human experience from a subjective perspective, using this description as a method to analyze and evaluate philosophical problems across various fields such as epistemology, ontology, philosophy of mind, and ethics. The founder of phenomenology was Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), who emphasized the importance of suspending all antecedent beliefs to achieve a pure and unbiased description of experience as it unfolds.[89] His student, Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), adopted this method into an approach he termed fundamental ontology. Heidegger explored how human pre-understanding of reality shapes the experience of and engagement with the world. He argued that pure description alone is insufficient for phenomenology and should be accompanied by interpretation to uncover and avoid possible misunderstandings.[90] This line of thought was further developed by his student Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900–2002), who held that human pre-understanding is dynamic and evolves through the process of interpretation. Gadamer explained this process as a fusion of horizons, which involves an interplay between the interpreter's current horizon and the horizon of the object being interpreted.[91]

Another influential aspect of Heidegger's philosophy is his focus on how humans care about the world. He explored how this concern is related to phenomena such as anxiety and authenticity. These ideas influenced Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980), who developed the philosophy of existentialism. Existentialists hold that humans are fundamentally free and responsible for their choices. They also assert that life lacks a predetermined purpose, and the act of choosing one's path without such a guiding purpose can lead to anxiety. The idea that the universe is inherently meaningless was especially emphasized by absurdist thinkers like Albert Camus (1913–1960).[92]

Critical Theory emerged in the first half of the 20th century within the Frankfurt School of philosophy. It is a form of social philosophy that aims to provide a reflective assessment and critique of society and culture. Unlike traditional theory, its goal is not only to understand and explain but also to bring about practical change, particularly to emancipate people and liberate them from domination and oppression. Key themes of Critical Theory include power, inequality, social justice, and the role of ideology. Notable figures include Theodor Adorno (1903–1969), Max Horkheimer (1895–1973), and Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979).[93]

The second half of 20th-century continental philosophy was marked by a critical attitude toward many traditional philosophical concepts and assumptions, such as truth, objectivity, universal explanations, reason, and progress. This outlook is sometimes labeled postmodernism. Michel Foucault (1926–1984) examined the relationship between knowledge and power, arguing that knowledge is always shaped by power. Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which aims to expose hidden contradictions within philosophical texts by subverting the oppositions they rely on, such as the opposition between presence and absence or between subject and object. Gilles Deleuze (1925–1995) drew on psychoanalytic theory to critique and reimagine traditional concepts like desire, subjectivity, identity, and knowledge.[94]

Arabic–Persian

[edit]Arabic–Persian philosophy refers to the philosophical tradition associated with the intellectual and cultural heritage of Arabic- and Persian-speaking regions. This tradition is also commonly referred to as Islamic philosophy or philosophy in the Islamic world.[95]

The classical period of Arabic–Persian philosophy began in the early 9th century CE, roughly 200 years after the death of Muhammad. It continued until the late 12th century CE and was an integral part of the Islamic Golden Age. The early classical period, prior to the work of Avicenna, focused particularly on the translation and interpretation of Ancient Greek philosophy. The late classical period, following Avicenna, was shaped by the engagement with his comprehensive philosophical system.[96]

Arabic–Persian philosophy had a profound influence on Western philosophy. During the early medieval period, many of the Greek texts were unavailable in Western Europe. They became accessible in the later medieval period largely due to their preservation and transmission by the Arabic–Persian intellectual tradition.[97]

Kalam and early classical

[edit]The early Arabic intellectual tradition before the classical period was characterized by various theological discussions, primarily focused on understanding the correct interpretation of Islamic revelation. Some historians view this as part of Arabic–Persian philosophy, while others draw a more narrow distinction between theology (kalam) and philosophy proper (falsafa). Theologians, who implicitly accepted the truth of revelation, restricted their inquiries to religious topics, such as proofs of the existence of God. Philosophers, on the other hand, investigated a broader range of topics, including those not directly covered by the scriptures.[98]

Early classical Arabic–Persian philosophy was strongly influenced by Ancient Greek philosophy, particularly the works of Aristotle, but also other philosophers such as Plato. This influence came through both translations and comprehensive commentaries. A key motivation for this process was to integrate and reconcile Greek philosophy with Islamic thought. Islamic philosophers emphasized the role of rational inquiry and examined how to harmonize reason and revelation.[99]

Al-Kindi (801–873) is often considered the first philosopher of this tradition, in contrast to the more theological works of his predecessors.[100] He followed Aristotle in regarding metaphysics as the first philosophy and the highest science. From his theological perspective, metaphysics studies the essence and attributes of God. He drew on Plotinus's doctrine of the One to argue for the oneness and perfection of God. For Al-Kindi, God emanates the universe by "bringing being to be from non-being." In the field of psychology, he argued for a dualism that strictly distinguishes the immortal soul from the mortal body. Al-Kindi was a prolific author, producing around 270 treatises during his lifetime.[101]

Al-Farabi (c. 872–950), strongly influenced by Al-Kindi, accepted his emanationist theory of creation. Al-Farabi claimed that philosophy, rather than theology, is the best pathway to truth. His interest in logic earned him the title "the Second Master" after Aristotle. He concluded that logic is universal and forms the foundation of all language and thought, a view that contrasts with certain passages in the Quran that assign this role to Arabic grammar. In his political philosophy, Al-Farabi endorsed Plato's idea that a philosopher-king would be the best ruler. He discussed the virtues such a ruler should possess, the tasks they should undertake, and why this ideal is rarely realized. Al-Farabi also provided an influential classification of the different sciences and fields of inquiry.[102]

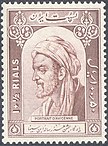

Later classical

[edit]Avicenna (980–1037) drew on the philosophies of the Ancient Greeks and Al-Farabi to develop a comprehensive philosophical system aimed at providing a holistic and rational understanding of reality that encompasses science, religion, and mysticism. He regarded logic as the foundation of rational inquiry. In the field of metaphysics, Avicenna argued that substances can exist independently, while accidents always depend on something else to exist. For example, color is an accident that requires a body to manifest. Avicenna distinguished between two forms of existence: contingent existence and necessary existence. He posited that God has necessary existence, meaning that God's existence is inherent and not dependent on anything else. In contrast, everything else in the world is contingent, meaning that it was caused by God and depends on Him for its existence. In psychology, Avicenna viewed souls as substances that give life to beings. He categorized souls into different levels: plants possess the simplest form of souls, while the souls of animals and humans have additional faculties, such as the ability to move, sense, and think rationally. In ethics, Avicenna advocated for the pursuit of moral perfection, which can be achieved by adhering to the teachings of the Quran. His philosophical system profoundly influenced both Islamic and Western philosophy.[103]

Al-Ghazali (1058–1111) was highly critical of Avicenna's rationalist approach and his adoption of Greek philosophy. He was skeptical of reason's ability to arrive at a true understanding of reality, God, and religion. Al-Ghazali viewed the philosophy of other Islamic philosophers as problematic, describing it as an illness. In his influential work, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, he argued that many philosophical teachings were riddled with contradictions and incompatible with Islamic faith. However, Al-Ghazali did not completely reject philosophy; he acknowledged its value but believed it should be subordinate to a form of mystical intuition. This intuition, according to Al-Ghazali, relied on direct personal experience and spiritual insight, which he considered essential for attaining a deeper understanding of reality.[104]

Averroes (1126–1198) rejected Al-Ghazali's skeptical outlook and sought to demonstrate the harmony between the philosophical pursuit of knowledge and the spiritual dimensions of faith. Averroes' philosophy was heavily influenced by Aristotle, and he frequently criticized Avicenna for diverging too much from Aristotle's teachings. In the field of psychology, Averroes proposed that there is only one universal intellect shared by all humans. Although Averroes' work did not have a significant impact on subsequent Islamic scholarship, it had a considerable influence on European philosophy.[105]

Post-classical

[edit]Averroes is often considered the last major philosopher of the classical era of Islamic philosophy. The traditional view holds that the post-classical period was marked by a decline on several levels. This decline is understood both in terms of the global influence of Islam and in the realm of scientific and philosophical inquiry within the Islamic world. Al-Ghazali's skepticism regarding the power of reason and the role of philosophy played a significant part in this development, leading to a shift in focus towards theology and religious doctrine.[106] However, some contemporary scholars have questioned the extent of this so-called decline. They argue that it is better understood as a shift in philosophical interest rather than an outright decline. According to this view, philosophy did not disappear but was instead integrated into and continued within the framework of theology.[107]

Mulla Sadra (1571–1636) is often regarded as the most influential philosopher of the post-classical era. He was a prominent figure in the philosophical and mystical school known as illuminationism. Mulla Sadra saw philosophy as a spiritual practice aimed at fostering wisdom and transforming oneself into a sage. His metaphysical theory of existence was particularly influential. He rejected the traditional Aristotelian notion that reality is composed of static substances with fixed essences. Instead, he advocated a process philosophy that emphasized continuous change and novelty. According to this view, the creation of the world is not a singular event in the past but an ongoing process. Mulla Sadra synthesized monism and pluralism by claiming that there is a transcendent unity of being that encompasses all individual entities. He also defended panpsychism, arguing that all entities possess consciousness to varying degrees.[108]

The movement of Islamic modernism emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries in response to the cultural changes brought about by modernity and the increasing influence of Western thought. Islamic modernists aimed to reassess the role of traditional Islamic doctrines and practices in the modern world. They sought to reinterpret and adapt Islamic teachings to demonstrate how the core tenets of Islam are compatible with modern principles, particularly in areas such as democracy, human rights, science, and the response to colonialism.[109]

Indian

[edit]Indian philosophy is the philosophical tradition that originated on the Indian subcontinent. It can be divided into three main periods: the ancient period, which lasted until the end of the 2nd century BCE,[b] the classical and medieval period, which lasted until the end of the 18th century CE, and the modern period that followed.[111] Indian philosophy is characterized by a deep interest in the nature of ultimate reality, often relating this topic to spirituality and asking questions about how to connect with the divine and reach a state of enlightenment. In this regard, Indian philosophers frequently served as gurus, guiding spiritual seekers.[112]

Indian philosophy is traditionally divided into orthodox and heterodox schools of thought, referred to as āstikas and nāstikas. The exact definitions of these terms are disputed. Orthodox schools typically accept the authority of the Vedas, the religious scriptures of Hinduism, and tend to acknowledge the existence of the self (Atman) and ultimate reality (Brahman). There are six orthodox schools: Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika, Sāṃkhya, Yoga, Mīmāṃsā, and Vedānta. The heterodox schools are defined negatively, as those that do not adhere to the orthodox views. The main heterodox schools are Buddhism and Jainism.[113]

Ancient

[edit]

The ancient period of Indian philosophy began around 900 BCE and lasted until 200 BCE. During this time, the Vedas were composed. These religious texts form the foundation of much of Indian philosophy, covering a wide range of topics, including hymns and rituals. Of particular philosophical interest are the Upanishads, which are late Vedic texts that discuss profound philosophical topics. Some scholars consider the Vedas as part of philosophy proper, while others view them as a form of proto-philosophy. This period also saw the emergence of non-Vedic movements, such as Buddhism and Jainism.[114]

The Upanishads introduce key concepts in Indian philosophy, such as Atman and Brahman. Atman refers to the self, regarded as the eternal soul that constitutes the essence of every conscious being. Brahman represents the ultimate reality and the highest principle governing the universe. The Upanishads explore the relationship between Atman and Brahman, with a key idea being that understanding their connection is a crucial step on the spiritual path toward liberation. Some Upanishads advocate an ascetic lifestyle, emphasizing withdrawal from the world to achieve self-realization. Others emphasize active engagement with the world, rooted in the belief that individuals have social duties to their families and communities. These duties are prescribed by the concept of dharma, which varies according to one's social class and stage of life. Another influential idea from this period is the concept of rebirth, where individual souls are caught in a cycle of reincarnation. According to this belief, a person's actions in previous lives determine their circumstances in future lives, a principle known as the law of karma.[115]

While the Vedas had a broad influence, not all Indian philosophical traditions originated from them. For example, the non-Vedic movements of Buddhism and Jainism emerged in the 6th century BCE. These movements agreed with certain Vedic teachings about the cycle of rebirth and the importance of seeking liberation but rejected many of the rituals and the social hierarchy described in the Vedas. Buddhism was founded by Gautama Siddhartha (563–483 BCE), who challenged the Vedic concept of Atman by arguing that there is no permanent, stable self. He taught that the belief in a permanent self leads to suffering and that liberation can be attained by realizing the absence of a permanent self.[116]

Jainism was founded by Mahavira (599–527 BCE). Jainism emphasizes respect for all forms of life, a principle expressed in its commitment to non-violence. This principle prohibits harming or killing any living being, whether in action or thought. Another central tenet of Jainism is the doctrine of non-absolutism, which posits that reality is complex and multifaceted, and thus cannot be fully captured by any single perspective or expressed adequately in language. The third pillar of Jainism is the practice of asceticism or non-attachment, which involves detaching oneself from worldly possessions and desires to avoid emotional entanglement with them.[117]

Classical and medieval

[edit]The classical and medieval periods in Indian philosophy span roughly from 200 BCE to 1800 CE. Some scholars refer to this entire duration as the "classical period," while others divide it into two distinct periods: the classical period up until 1300 CE, and the medieval period afterward. During the first half of this era, the orthodox schools of Indian philosophy, known as the darsanas, developed. Their foundational scriptures usually take the form of sūtras, which are aphoristic or concise texts that explain key philosophical ideas. The latter half of this period was characterized by detailed commentaries on these sutras, aimed at providing comprehensive explanations and interpretations.[118]

Samkhya is the oldest of the darśanas. It is a dualistic philosophy that asserts that reality is composed of two fundamental principles: Purusha, or pure consciousness, and Prakriti, or matter. Samkhya teaches that Prakriti is characterized by three qualities known as gunas. Sattva represents calmness and harmony, Rajas corresponds to passion and activity, and Tamas involves ignorance and inertia.[119] The Yoga school initially formed a part of Samkhya and later became an independent school. It is based on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali and emphasizes the practice of physical postures and various forms of meditation.[120]

Nyaya and Vaisheshika are two other significant orthodox schools. In epistemology, Nyaya posits that there are four sources of knowledge: perception, inference, analogical reasoning, and testimony. Nyaya is particularly known for its theory of logic, which emphasizes that inference depends on prior perception and aims to generate new knowledge, such as understanding the cause of an observed phenomenon. Vaisheshika, on the other hand, is renowned for its atomistic metaphysics. Although Nyaya and Vaisheshika were originally distinct schools, they later became intertwined and were often treated as a single tradition.[121]

The schools of Vedānta and Mīmāṃsā focus primarily on interpreting the Vedic scriptures. Vedānta is concerned mainly with the Upanishads, discussing metaphysical theories and exploring the possibilities of knowledge and liberation. In contrast, Mīmāṃsā is more focused on the ritualistic practices outlined in the Vedas.[122]

Buddhist philosophy also flourished during this period, leading to the development of four main schools of Indian Buddhism: Sarvāstivāda, Sautrāntika, Madhyamaka, and Yogācāra. While these schools agree on the core teachings of Gautama Buddha, they differ on certain key points. The Sarvāstivāda school holds that "all exists," including past, present, and future entities. This view is rejected by the Sautrāntika school, which argues that only the present exists. The Madhyamaka school, founded by Nagarjuna (c. 150–250 CE), asserts that all phenomena are inherently empty, meaning that nothing possesses a permanent essence or independent existence. The Yogācāra school is traditionally interpreted as a form of idealism, arguing that the external world is an illusion created by the mind.[123]

The latter half of the classical period saw further developments in both the orthodox and heterodox schools of Indian philosophy, often through detailed commentaries on foundational sutras. The Vedanta school gained significant influence during this time, particularly with the rise of the Advaita Vedanta school under Adi Shankara (c. 700–750 CE). Shankara advocated for a radical form of monism, asserting that Atman and Brahman are identical, and that the apparent multiplicity of the universe is merely an illusion, or Maya.[124]

This view was modified by Ramanuja (1017–1137 CE),[c] who developed the Vishishtadvaita Vedanta school. Ramanuja agreed that Brahman is the ultimate reality, but he argued that individual entities, such as qualities, persons, and objects, are also real as parts of the underlying unity of Brahman.[126] He emphasized the importance of Bhakti, or devotion to the divine, as a spiritual path and was instrumental in popularizing the Bhakti movement, which continued until the 17th to 18th centuries.[127]

Another significant development in this period was the emergence of the Navya-Nyāya movement within the Nyaya school, which introduced a more sophisticated framework of logic with a particular focus on linguistic analysis.[128]

Modern

[edit]The modern period in Indian philosophy began around 1800 CE, during a time of social and cultural changes, particularly due to the British rule and the introduction of English education. These changes had various effects on Indian philosophers. Whereas previously, philosophy was predominantly conducted in the language of Sanskrit, many philosophers of this period began to write in English. An example of this shift is the influential multi-volume work A History of Indian Philosophy by Surendranath Dasgupta (1887–1952). Philosophers during this period were influenced both by their own traditions and by new ideas from Western philosophy.[129]

During this period, various philosophers attempted to create comprehensive systems that would unite and harmonize the diverse philosophical and religious schools of thought in India. For example, Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902) emphasized the validity and universality of all religions. He used the principles of Advaita Vedanta to argue that different religious traditions are merely different paths leading to the same spiritual truth. According to Advaita Vedanta, there is only one ultimate reality, without any distinctions or divisions. This school of thought considers the diversity and multiplicity in the world as an illusion that obscures the underlying divine oneness. Vivekananda believed that different religions represent various ways of realizing this divine oneness.[130]

A similar project was pursued by Sri Aurobindo in his integral philosophy. His complex philosophical system seeks to demonstrate how different historical and philosophical movements are part of a global evolution of consciousness.[131] Other contributions to modern Indian philosophy were made by spiritual teachers like Sri Ramakrishna, Ramana Maharshi, and Jiddu Krishnamurti.[132]

Chinese

[edit]Chinese philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought associated with the intellectual and cultural heritage of China. Various periodizations of this tradition exist. One common periodization divides Chinese philosophy into four main eras: an early period before the Qin dynasty, a period up to the emergence of the Song dynasty, a period lasting until the end of the Qing dynasty, and a modern era that follows. The three main schools of Chinese philosophy are Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Other influential schools include Mohism and Legalism.[133]

In traditional Chinese thought, philosophy was not distinctly separated from religious thought and other types of inquiry.[134] It was primarily concerned with ethics and societal matters, often placing less emphasis on metaphysics compared to other traditions. Philosophical practice in China tended to focus on practical wisdom, with philosophers often serving as sages or thoughtful advisors.[135]

Pre-Qin

[edit]The first period in Chinese philosophy began in the 6th century BCE and lasted until the rise of the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE.[136] The concept of Dao, often translated as "the Way," played a central role during this period, with different schools of thought interpreting it in various ways. Early Chinese philosophy was heavily influenced by the teachings of Confucius (551–479 BCE). Confucius emphasized that a good life is one that aligns with the Dao, which he understood primarily in terms of moral conduct and virtuous behavior. He argued for the importance of filial piety, the respect for one's elders, and advocated for universal altruism. In Confucian thought, the family is fundamental, with each member fulfilling their role to ensure the family's overall flourishing. Confucius extended this idea to society, viewing the state as a large family where harmony is essential.[137]

Laozi (6th century BCE) is traditionally regarded as the founder of Daoism. Like Confucius, he believed that living a good life involves being in harmony with the Dao. However, unlike Confucius, Laozi focused not only on society but also on the relationship between humans and nature. His concept of wu wei, often translated as "effortless action," was particularly influential. It refers to acting in a natural, spontaneous way that is in accordance with the Dao, which Laozi saw as an ideal state of being characterized by ease and spontaneity.[138]

The Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi (399–295 BCE) employed parables and allegories to express his ideas. To illustrate the concept of wu wei in daily life, he used the example of a butcher who, after years of practice, could cut an ox effortlessly, with his knife naturally following the optimal path without any conscious effort. Zhuangzi is also famous for his story of the butterfly dream, which explores the nature of subjective experience. In this story, Zhuangzi dreams of being a butterfly and, upon waking, questions whether he is a man who dreamt of being a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming of being a man.[139]

The school of Mohism was founded by Mozi (c. 470–391 BCE). Central to Mozi's philosophy is the concept of jian ai, which advocates for universal love or impartial caring. Based on this concept, he promoted an early form of consequentialism, arguing that political actions should be evaluated based on how they contribute to the welfare of the people.[140]

Qin to pre-Song dynasties

[edit]The next period in Chinese philosophy began with the establishment of the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE and lasted until the rise of the Song dynasty in 960 CE. This period was influenced by Xuanxue philosophy, legalist philosophy, and the spread of Buddhism. Xuanxue, also known as Neo-Daoism, sought to synthesize Confucianism and Daoism while developing a metaphysical framework for these schools of thought. It posited that the Dao is the root of ultimate reality, leading to debates about whether this root should be understood as being or non-being. Philosophers such as He Yan (c. 195–249 CE) and Wang Bi (226–249 CE) argued that the Dao is a formless non-being that acts as the source of all things and phenomena. This view was contested by Pei Wei (267–300 CE), who claimed that non-being could not give rise to being; instead, he argued that being gives rise to itself.[141]

In the realm of ethics and politics, the school of Legalism became particularly influential. Legalists rejected the Mohist idea that politics should aim to promote general welfare. Instead, they argued that statecraft is about wielding power and establishing order. They also dismissed the Confucian emphasis on virtues and moral conduct as the foundation of a harmonious society. In contrast, Legalists believed that the best way to achieve order was through the establishment of strict laws and the enforcement of punishments for those who violated them.[142]

Buddhism, which arrived in China from India in the 1st century CE, initially focused on the translation of original Sanskrit texts into Chinese. Over time, however, new and distinctive forms of Chinese Buddhism emerged. For instance, Tiantai Buddhism, founded in the 6th century CE, introduced the doctrine of the Threefold Truth, which sought to reconcile two opposing views. The first truth, conventional realism, affirms the existence of ordinary things. The second truth posits that all phenomena are illusory or empty. The third truth attempts to reconcile these positions by claiming that the mundane world is both real and empty at the same time. This period also witnessed the rise of Chan Buddhism, which later gave rise to Zen Buddhism in Japan. In epistemology, Chan Buddhists advocated for a form of immediate acquaintance with reality, asserting that it transcends the distortions of linguistic distinctions and leads to direct knowledge of ultimate reality.[143]

Song to Qing dynasties and modern

[edit]The next period in Chinese philosophy began with the emergence of the Song dynasty in 960 CE. Some scholars consider this period to end with the Opium Wars in 1840, while others extend it to the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912. During this era, neo-Confucianism became particularly influential. Unlike earlier forms of Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism placed greater emphasis on metaphysics, largely in response to similar developments in Daoism and Buddhism. It rejected the Daoist and Buddhist focus on non-being and emptiness, instead centering on the concept of li as the positive foundation of metaphysics. Li is understood as the rational principle that underlies being and governs all entities. It also forms the basis of human nature and is the source of virtues. Li is often contrasted with qi, which is seen as a material and vital force.[144]

The later part of the Qing dynasty and the subsequent modern period were marked by an encounter with Western philosophy, including the ideas of philosophers like Plato, Kant, and Mill, as well as movements like pragmatism. However, Marx's ideas of class struggle, socialism, and communism were particularly significant. His critique of capitalism and his vision of a classless society led to the development of Chinese Marxism. In this context, Mao Zedong (1893–1976) played a dual role as both a philosopher who expounded these ideas and a revolutionary leader committed to their practical implementation. Chinese Marxism diverged from classical Marxism in several ways. For instance, while classical Marxism assigns the proletariat the responsibility for both the rise of the capitalist economy and the subsequent socialist revolution, in Mao's Marxism, this role is assigned to the peasantry under the guidance of the Communist Party.[145]

Traditional Chinese thought also remained influential during the modern period. This is exemplified in the philosophy of Liang Shuming (1893–1988), who was influenced by Confucianism, Buddhism, and Western philosophy. Liang is often regarded as a founder of New Confucianism. He advocated for a balanced life characterized by harmony between humanity and nature as the path to true happiness. Liang criticized the modern European attitude for its excessive focus on exploiting nature to satisfy desires, and he viewed the Indian approach, with its focus on the divine and renunciation of desires, as an extreme in the opposite direction.[147]

Others

[edit]Various philosophical traditions developed their own distinctive ideas. In some cases, these developments occurred independently, while in others, they were influenced by the major philosophical traditions.[148]

Japanese

[edit]Japanese philosophy is characterized by its engagement with various traditions, including Chinese, Indian, and Western schools of thought. Ancient Japanese philosophy was shaped by Shinto, the indigenous religion of Japan, which included a form of animism that saw natural phenomena and objects as spirits, known as kami. The arrival of Confucianism and Buddhism in the 5th and 6th centuries CE transformed the intellectual landscape and led to various subsequent developments. Confucianism influenced political and social philosophy and was further developed into different strands of neo-Confucianism. Japanese Buddhist thought evolved particularly within the traditions of Pure Land Buddhism and Zen Buddhism.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, interaction with Western thinkers had a major influence on Japanese philosophy, particularly through the schools of existentialism and phenomenology. This period saw the foundation of the Kyoto School, established by Kitaro Nishida (1870–1945). Nishida criticized Western philosophy, particularly Kantianism, for its reliance on the distinction between subject and object. He sought to overcome this dichotomy by developing the concept of basho, which is usually translated as "place" and may be understood as an experiential domain that transcends the subject-object distinction. Other influential members of the Kyoto School include Tanabe Hajime (1885–1962) and Nishitani Keiji (1900–1990).[149]

Latin American

[edit]Philosophy in Latin America is often considered part of Western philosophy. However, in a more specific sense, it represents a distinct tradition with its own unique characteristics, despite strong Western influence. Philosophical ideas concerning the nature of reality and the role of humans within it can be found in the region's indigenous civilizations, such as the Aztecs, the Maya, and the Inca. These ideas developed independently of European influence. However, most discussions typically focus on the colonial and post-colonial periods, as very few texts from the pre-colonial period have survived.

The colonial period was dominated by religious philosophy, particularly in the form of scholasticism. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the emphasis shifted to Enlightenment philosophy and the adoption of a scientific outlook, particularly through positivism. An influential current in the later part of the 20th century was the philosophy of liberation, which was inspired by Marxism and focused on themes such as political liberation, intellectual independence, and education.[150]

African

[edit]

In the broadest sense, African philosophy encompasses philosophical ideas that originated across the entire African continent. However, the term is often understood more narrowly to refer primarily to the philosophical traditions of Western and sub-Saharan Africa.[151] The philosophical tradition in Africa draws from both ancient Egypt and scholarly texts from medieval Africa.[152] While early African intellectual history primarily focused on folklore, wise sayings, and religious ideas, it also included philosophical concepts, such as the idea of Ubuntu. Ubuntu is usually translated as "humanity" or "humanness" and emphasizes the deep moral connections between people, advocating for kindness and compassion.[151]

African philosophy before the 20th century was primarily conducted and transmitted orally as ideas by philosophers whose names have been lost to history.[d] This changed in the 1920s with the emergence of systematic African philosophy. A significant movement during this period was excavationism, which sought to reconstruct traditional African worldviews, often with the goal of rediscovering a lost African identity. However, this approach was contested by Afro-deconstructionists, who questioned the existence of a singular African identity. Other influential strands and topics in modern African thought include ethnophilosophy, négritude, pan-Africanism, Marxism, postcolonialism, and critiques of Eurocentrism.[154]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Some historians also include pragmatism as a third tradition.[75]

- ^ The exact periodization is disputed, with some sources stating it ended as early as 500 BCE, while others argue it lasted until 200 CE.[110]

- ^ These dates are traditionally cited, but some recent scholars suggest that his life spanned from 1077 to 1157 CE.[125]

- ^ One exception are the works of the 17th-century Ethiopian philosopher Zera Yacob.[153]

Citations

[edit]- ^

- Santinello & Piaia 2010, pp. 487–488

- Copleston 2003, pp. 4–6

- Verene 2008, pp. 6–8

- ^

- Scharfstein 1998, pp. 1–4

- Perrett 2016, Is there Indian philosophy?

- Smart 2008, pp. 1–3

- Rescher 2014, p. 173

- Parkinson 2005, pp. 1–2

- ^

- Catana 2013, pp. 115–118

- Verene 2008, pp. 6–8

- Frede 2022, p. x

- Beaney 2013, p. 60

- Chimisso 2016, p. 59

- ^

- Graham 1988, pp. 158–159

- Priel 2020, p. 213

- ^

- Piercey 2011, pp. 109–111

- Mormann 2010, p. 33

- ^

- Gracia 2006

- Lamprecht 1939, pp. 449–451