Aurvandill

Aurvandill (Old Norse) is a figure in Germanic mythology. In Norse mythology, the god Thor tosses Aurvandill's toe – which had frozen while the thunder god was carrying him in a basket across the Élivágar rivers – into the sky to form a star called Aurvandils-tá ('Aurvandill's toe'). In wider medieval Germanic-speaking cultures, he was known as Ēarendel in Old English, Aurendil in Old High German, Auriwandalo in Lombardic, and possibly as auzandil in Gothic. An Old Danish Latinized version, Horwendillus (Ørvendil), is also the name given to the father of Amlethus (Amleth) in Saxo Grammaticus' Gesta Danorum.[1][2][3] Comparative studies of the various myths where the figure is involved have led scholars to reconstruct a Common Germanic mythical figure named *Auza-wandilaz, which seems to have personified the 'rising light' of the morning, possibly the Morning Star (Venus). However, the German and – to a lesser extent – the Old Danish evidence remain difficult to interpret in this model.[4][5][2][6]

Name and origin

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The Old Norse name Aurvandill stems from a Proto-Germanic form reconstructed as *Auza-wandilaz,[1] *Auzi-wandalaz,[7] or *Auzo-wandiloz.[8] It is cognate with Old English Ēarendel, Old High German Aurendil (≈ Orentil), and Lombardic Auriwandalo.[1][2][9] The Gothic word auzandil, translating the Koine Greek ἑωσφόρος (eosphoros, 'dawnbringer'), may also be related.[9]

The original meaning of the Common Germanic name remains obscure.[1][5][2] The most semantically plausible explanation is to interpret *Auza-wandilaz as a compound meaning 'light-beam' or 'ray of light', by deriving the prefix *auza- from Proto-Germanic *auzom ('shiny [especially of liquids]'; cf. ON aurr 'gold', OE ēar 'wave, sea'),[note 1] and *-wandilaz from *wanđuz ('rod, cane'; cf. Goth. wandus, ON vǫndr).[note 2][12] The latter probably stems from the root *wanđ- ('to turn, wind'), so that the etymological connotation is that of suppleness or flexibility.[11] This theory is encouraged by the Old English association of the idea of 'rising light' with Ēarendel,[13][14][15] whose name has been translated as 'radiance, morning star',[5][16][9] or as 'dawn, ray of light'.[17]

Alternatively, the Old Norse prefix aur- has also been interpreted as coming from Proto-Germanic *aura- ('mud, gravel, sediment'; cf. ON aurr 'wet clay, mud', OE ēar 'earth'), with Aurvandill being rendered as 'gravel-beam' or 'swamp-wand'.[18][19][20] According to philologist Christopher R. Fee, this may imply the idea a phallic figure related to fertility, the name of his spouse in the Old Norse myth, Gróa, literally meaning 'Growth'.[20]

In less frequent scholarly interpretations, the second element has also been derived by some researchers from *wanđilaz ('Vandal'; i.e. 'the shining Vandal'),[21] from a stem *wandila- ('beard'),[22] or else compared to a Norse word for sword.[23]

Origin

[edit]Commentators since at least the time of Jacob Grimm's Deutsche Mythologie, first published in 1835, have emphasized the great age of the tradition reflected in the mythological material surrounding this name, without being able to fully reconstruct the motifs of a Common Germanic myth. The task is complicated because the mythical stories of Orendel and Horwendillus appear to be unrelated to that of Ēarendel and Aurvandill. However, some scholars, including Georges Dumézil, have attempted to demonstrate that Saxo's Horwendillus and Snorri's Aurvandill are based on the same archetypal myth.[5] Furthermore, the apparent discrepancies may be explained by the fact that derivatives of *Auza-wandilaz were also used as personal names in the Lombardic and German traditions, as attested by historical figures who are named Auriwandalo and Aurendil by the 8th century AD.[4][24][9] Thus, the Orendel of the Middle High German myth may have been a different figure sharing the same name.[4]

At any rate, scholars Rudolf Simek and John Lindow contend that the linguistic relation between the Old Norse and Old English names may suggest a Common Germanic origin of the myth despite the absence of Aurvandill from the Poetic Edda. They argue that Aurvandill was probably already connected with a star in the original myth, but that Snorri may have modelled the story of Aurvandils-tá ('Auvandill's Toe') on the tale of the stars emerging from Þjazi's eyes while Thor throws them into the sky.[16][17]

Attestations

[edit]Old Norse

[edit]The Old Norse Aurvandill is mentioned once in Norse mythology, in Skáldskaparmál, a book of Snorri Sturluson's 13th-century Prose Edda, where he is described as the husband of the witch Gróa:[25]

Thor went home to Thrúdvangar, and the hone remained sticking in his head. Then came the wise woman who was called Gróa, wife of Aurvandill the Valiant: she sang her spells over Thor until the hone was loosened. But when Thor knew that, and thought that there was hope that the hone might be removed, he desired to reward Gróa for her leech-craft and make her glad, and told her these things: that he had waded from the north over Icy Stream and had borne Aurvandill in a basket on his back from the north out of Jötunheim. And he added for a token, that one of Aurvandill's toes had stuck out of the basket, and became frozen; wherefore Thor broke it off and cast it up into the heavens, and made thereof the star called Aurvandill's Toe. Thor said that it would not be long ere Aurvandill came home: but Gróa was so rejoiced that she forgot her incantations, and the hone was not loosened, and stands yet in Thor's head. Therefore it is forbidden to cast a hone across the floor, for then the hone is stirred in Thor's head.

This passage seems to be part of a larger story where Aurvandill is abducted by the jǫtnar; the thunder-god Thor confronts one of them (Hrungnir in Snorri's version) and eventually liberates Aurvandill, but leaves the scene with the weapon of the jǫtunn stuck in his head.[26]

At the end of the story, Aurvandill's frost-bitten toe is made into a new star by Thor. However, it is not clear what celestial object is indicated in this passage. Guesses as to the identity of this star have included Sirius, the planet Venus, or the blue-white star Rigel, which could be viewed as forming the foot of the constellation Orion.[27]

Gothica Bononiensia

[edit]The oldest attestation of this name may occur in the Gothica Bononiensia, a sermon from Ostrogothic Italy written in the Gothic language not later than the first half of the 6th century, and discovered in 2009.[28] On folio 2 recto, in the context of a quotation from Isaiah 14:12, linguist P. A. Kerkhof suggested to see the word 𐌰𐌿𐌶𐌰𐌽𐌳𐌹𐌻 (auzandil) in a difficult-to-read part of the palimpsest. This reading, which has been accepted by various experts such as Carla Falluomini and Roland Schuhmann,[29] translates the Koine Greek word ἑωσφόρος (heōsphóros, 'dawnbringer') from the Septuagint, which in Latin is rendered lucifer ('light-bringer, morning star'):[3]

... ƕaiwa usdraus us himina auzandil sa in maurgin urrinnanda ...

... how Lucifer did fall from heaven, he who emerges in the morning ...

Old English

[edit]The term ēarendel (≈ eorendel, earendil) appears only seven times in the Old English corpus, where it is used in certain contexts to interpret the Latin oriens ('rising sun'), lucifer ('light-bringer'), aurora ('dawn') or iubar ('radiance').[30] According to scholar J. E. Cross, textual evidence indicate that it originally meant 'coming or rising light, beginning of light, bringer of light', and that later innovations led to an extended meaning of 'radiance, light'.[31] Philologist Tiffany Beechy writes that "the evidence from the early glossary tradition shows earendel to be a rare alternative for common words for the dawn/rising sun."[32] According to her, the "Anglo-Saxons appear to have known earendel as a quasi-mythological figure who personified a natural phenomenon (sunrise) and an astrological/astronomical object (the morning star)."[33]

Crist I

[edit]The lines 104–108 of the Old English poem Crist I (Christ I) describe the coming of Ēarendel to the earth:

Crist I (104–108):[34]

| B. C. Row translation (1997):[35]

| T. Beechy translation (2010):[36]

|

The impetus of the poem comes from the Latin Advent antiphon: O Oriens, splendor lucis aeternae et sol justitiae: veni et illumina sedentem in tenebris et umbra mortis – "O Orient/Rising One, splendour of eternal light and sun of justice: come and illuminate one sitting in darkness and the shadow of death". Scholars agree that Ēarendel was chosen in Crist I as an equivalent of the Latin Oriens, understood in a religious-poetic context as the 'source of true light', 'the fount of light', and the 'light (which) rises from the Orient'.[37][38][39]

Ēarendel is traditionally taken to personify in Crist I either John the Baptist or Christ himself, figuring him as the rising sun, morning star, or dawn.[40] He is portrayed in the poem as the "true(st) light of the sun" (soðfæsta sunnan leoma) and the "brightest of angels [≈ messengers]" (engla beorhtast), implying the idea of a heavenly or divine radiance physically and metaphorically sent over the earth for the benefit of mankind. The lines 107b–8 (þu tida gehwaneof sylfum þe symle inlihtes), translated as "all spans of time you, of yourself, enlighten always", or as "you constantly enlighten all seasons by your presence", may also suggest that Ēarendel exists in the poem as an eternal figure situated outside of time, and as the very force that makes time and its perception possible.[41]

Beechy argues that the expression Ēalā Ēarendel ('O Ēarendel') could be an Old English poetic stock formula, as it finds "phonetic-associative echoes" in the expressions eorendel eall and eorendel eallunga from the Durham Hymnal Gloss.[42]

Blickling Homilies

[edit]Ēarendel also appears in the Blickling Homilies (10th c. AD), where he is explicitly identified with John the Baptist:

Blickling Homilies XIV (30–35):[43]

| R. Morris translation (1880):[43]

|

The passage is based on a Latin sermon by the 5th-century Archbishop of Ravenna Petrus Chrysologus: Sed si processurus est, iam nascatur Ioannes, quia instat nativitas Christi; surgat novus Lucifer, quia iubar iam veri Solis erumpit – "But since he is about to appear, now let John spring forth, because the birth of Christ follows closely; let the new Lucifer arise, because now the light of the true Sun is breaking forth". Since the Old English version is close to the original Latin, ēarendel can be clearly identified in the Blickling Homilies with lucifer, meaning in liturgical language the 'light bearer, the planet Venus as morning star, the sign auguring the birth of Christ'.[44][45] In this context, ēarendel is to be understood as the morning star, the light whose rising signifies Christ’s birth, and whose appearance comes in the poem before the "gleam of the true Sun, God himself".[45]

Glosses

[edit]In the Durham Hymnal Gloss (early 11th c. AD), the term ēarendel is used in specific contexts to gloss the Latin aurora ('dawn; east, orient') instead of the more frequent equivalent dægrima ('dawn'), with the hymns 15.8 and 30.1 implying that ēarendel appears with the dawn, as the light that "quite suffuses the sky", rather than being the dawn itself ("the dawn comes up in its course, eorendel steps fully forth").[46]

Durham Hymnal Gloss:[47][48]

| Old English version:[47][46]

|

The Épinal Glossary, written in England in the 8th century, associates ēarendel with the Latin iubar ('brightness, radiance' [especially of heavenly bodies]) as an alternative to the more frequent equivalent leoma (Old English: 'ray of light, gleam').[49][46] Two copies of the Épinal Glossary were made in the late 8th or early 9th century: the Épinal-Erfurt Glossary, which gives the equation leoma vel earendiI (≈ leoma vel oerendil), and the Corpus Glossary, redacted from an archetype of Épinal-Erfurt exemplar.[46]

German

[edit]The forms Aurendil (≈ Horindil, Urendil), dating from the 8th century, and Orendil (≈ Orentil), dating from the 9th–10th century, were used in Old High German as personal names.[50][24] A Bavarian count named Orendil is recorded in 843.[51]

The Middle High German epic poem Orendel, written in the late 12th century, provides a fictional account of how the Holy Mantle of Christ came to the city of Trier that was probably inspired by the actual transfer of the Mantle to the main altar of Trier Cathedral in 1196. The style of the poem, characterized by its "paratactic organization of episodes and the repetition of poetic formulas", may point to an older oral tradition.[52] The eponymous hero of the tale, Orendel, son of King Ougel, embarks on the sea with a mighty fleet in order to reach the Holy Land and seek the hand of Bride, Queen of Jerusalem. Suffering shipwreck, Orendel is rescued by a fisherman and eventually recovers the lost Mantle in the belly of a whale. The coat provides him protection and he succeeds in winning Bride for his wife. After ruling Jerusalem with Bride for a time, the two of them meet with many adventures. At the end of the story, Orendel finally disposes of the Holy Coat after bringing it to Trier.[52]

The appendix to the Strassburger Heldenbuch (15th c.) names King Orendel (≈ Erentel) of Trier as the first of the heroes that were ever born.[53][54]

The name also gave way to various toponyms found in present-day Germany, including Orendileshûs (in Grabfeld), Orendelsall (now part of Zweiflingen), and Orendelstein (in Öhringen).[55]

Lombardic

[edit]The Lombardic form Auriwandalo appears as a personal name in the 8th century.[24]

Danish

[edit]A Latinized version of the Old Danish name, Horwendillus (Ørvendil), appears in Saxo Grammaticus' Gesta Danorum (ca. 1200) as the father of Amlethus (Amlet):[56]

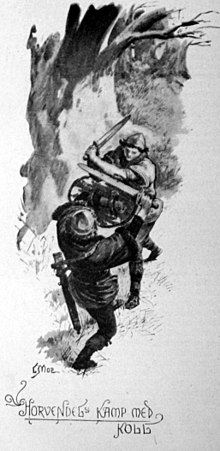

Now Ørvendil, after controlling the [Jutland] province for three years, had devoted himself to piracy and reaped such superlative renown that Koller, the king of Norway, wishing to rival his eminent deeds and widespread reputation, judged it would suit him very well if he could transcend him in warfare and cast a shadow over the brilliance of this world-famed sea-rover. He cruised about, combing various parts of the seas, until he lit upon Ørvendil's fleet. Each of the pirates had gained an island in the midst of the ocean and they had moored their ships on different sides. (...)

Both gave and accepted their word of honour on this point and fell to battle. They were not deterred from assailing each other with their blades by the novelty of their meeting or the springtime charm of that spot, for they took no heed of these things. Ørvendil's emotional fervour made him more eager to set upon his foe than to defend himself; consequently he disregarded the protection of his shield and laid both hands to his sword. This daring had its results. His rain of blows deprived Koller of his shield by cutting it to pieces; finally he carved off the other’s foot and made him fall lifeless. He honoured their agreement by giving him a majestic funeral, constructing an ornate tomb, and providing a ceremony of great magnificence. After this he hounded down and slew Koller's sister Sæla, a warring amazon and accomplished pirate herself and skilled in the trade of fighting.

Three years were passed in gallant military enterprises, in which he marked the richest and choicest of the plunder for Rørik, to bring himself into closer intimacy with the king. On the strength of their friendship Ørvendil wooed and obtained Rørik's daughter Gerutha for his bride, who bore him a son, Amleth.

In view of Saxo's tendency to euhemerise and reinterpret traditional Scandinavian myths, philologist Georges Dumézil has proposed that his story was based on the same archetype as Snorri's Aurvandill. In what could be a literary inversion of the original myth, Horwendillus is portrayed as a warrior who injures and vanquishes his adversary, whereas Aurvandill was taken as a hostage by the jǫtnar and wounded during his deliverance. Dumézil also notes that, although the event does not take a cosmological turn in Saxo's version, Aurvandill's toe was broken off by Thor, while Collerus' (Koller's) entire foot is slashed off by Horwendillus.[57]

In popular culture

[edit]The English writer J. R. R. Tolkien discovered the lines 104–105 of Cynewulf's Crist in 1913.[58] According to him, the "great beauty" of the name Ēarendel, and the myth he seems to be associated with, inspired the character of Eärendil depicted in The Silmarillion.[59] In 1914, Tolkien published a poem originally entitled "The Voyage of Earendel the Evening Star" as an account of Ēarendel's celestial course as the bright Morning-star.[27] In a personal letter from 1967, Tolkien wrote:

When first studying A[nglo]-S[axon] professionally (1913) ... I was struck by the great beauty of this word (or name), entirely coherent with the normal style of A-S, but euphonic to a peculiar degree in that pleasing but not 'delectable' language ... it at least seems certain that it belonged to astronomical-myth, and was the name of a star or star-group. Before 1914, I wrote a 'poem' upon Earendel who launched his ship like a bright spark from the havens of the Sun. I adopted him into my mythology in which he became a prime figure as a mariner, and eventually as a herald star, and a sign of hope to men. Aiya Earendil Elenion Ancalima (II 329) 'hail Earendil brightest of Stars' is derived at long remove from Éala Éarendel engla beorhtast.[59]

Tolkien interpreted Ēarendel as a messenger, probably inspired by his association with the word engel ('angel, messenger') in both Crist I (104) and the Blickling Homilies (21 & 35), and his identification with John the Baptist in the latter text.[27] Tolkien's depiction of Eärendil as a herald also has echoes in the interpretation of the Old English Ēarendel as the Morning-star physically heralding the rising of the sun, which finds a figurative parallel in the Blickling Homilies, where Ēarendel heralds the coming of the "true Sun", Christ.[60] Another pervasive aspect of Tolkien's Eärendil is his depiction as a mariner. Carl F. Hostetter notes that, although "the association of Eärendil with the sea was for Tolkien a deeply personal one", the Danish Horvandillus and the German Orendel are both portrayed as mariners themselves.[60]

In 2022, a group of scientists led by astronomer Brian Welch named star WHL0137-LS "Earendel" from the Old English meaning.[61][62]

In the 2022 revenge-thriller film The Northman, written and directed by Robert Eggers, Aurvandill is portrayed by Ethan Hawke. In the film Aurvandill is mentioned as the Raven King, who is the father of Amleth, the protagonist of the film, portrayed by the Swedish actor Alexander Skarsgård. The film is based primarily on the medieval Scandinavian legend of Amleth, which is the direct inspiration behind the character Hamlet from William Shakespeare's 16th century tragedy of the same name.[63]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e de Vries 1962, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e Simek 1984, pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b Falluomini 2017, pp. 288–291.

- ^ a b c de Vries 1957, pp. 137–138.

- ^ a b c d Dumézil 1970, p. 1171.

- ^ Lindow 2001, p. 65.

- ^ Hatto 1965, p. 70.

- ^ Ström & Biezais 1975, p. 139.

- ^ a b c d Falluomini 2017: "auzandil? (auzandil für auzandil‹s›?, Nom. Sing., M. a?; Bl. 2r, Z. 10; Wiedergabe von ἑωσφόρος) 'Luzifer'; vgl. ae. ēarendel 'Morgenstern' und ahd. PN Aurendil/Orentil (mit Varianten), vgl. auch an. Aurvandill/Örvandill und lang. Auriwandalo."

- ^ Beechy 2010, p. 15.

- ^ a b Oxford English Dictionary Online, wand, n.

- ^ de Vries 1962, p. 20; Simek 1984, pp. 31–32; Beechy 2010, p. 15.

- ^ de Vries 1962, p. 20: "Die deutungen gehen weit aus einander. z.B. < *Auza-wandilaz 'der glänzende Wandale’ so R. Much, Mitt, schles. ges. für Volksk. 27, 1926, 20ff; vgl. aurr (2) und austr (2) (aber weshalb dann kein R-umlaut?); aber derselbe forscher WS 4, 1912, 170-3 stellt -vandill zu vǫndr und deutet: ‘lichtstreif, lichtstrahl’ (ae Earendel also erst später als lichtheros aufgeffasst); wider anders F.R. Schröder GRM 26, 1938, 100 als 'sumpfgerte', also aus aurr (1) und vǫndr. Alles nur unsichere vermutungen." cf. aurr (2): "Das wort wird auch gedeutet als ‘glanz’ und in diesem fall entweder aus urgerm. *auzom 'glanz, glänzende flüssigkeit', verwandt mit oder oder entlehnt aus lat. aurum 'gold'."

- ^ Cross 1964, pp. 73–74: "Its precise translation into Modern English is, of course, not the concern of the critic who considers the poem in Anglo-Saxon, but some rendering to hold the equivalence – perhaps' rising light' – would be suitable."

- ^ Beechy 2010, p. 16: "The evidence from the early glossary tradition shows earendel to be a rare alternative for common words for the dawn/rising sun."

- ^ a b Simek 1984, pp. 31–32: "Snorri hat wohl die Anekdote zur Erklärung des Namens Aurvandils tá (d.i. 'Auvandills Zehe') nach dem Muster der Erzählung von der Entstelrung der Sterne aus Thjazis Augen nachgebildet. Aurvandill hatte aber sicherlich schon früher mit einem Stern zu tun, denn die altengl. Entsprechung des Namens Aurvandill, Earendel, ist ein Name für 'Glanz, Morgenstern'."

- ^ a b Lindow 2001, p. 65: "Although the etymology of the name is unknown, it is cognate with Old English earendel, "dawn, ray of light", so there may be a Germanic myth here, despite the absence of Aurvandil from the Norse poetic corpus. Thor also made stars out of Thjazi's eyes, and in my view we should read these acts as his contribution to cosmogony, an area in which he is otherwise absent."

- ^ Schröder 1938, p. 100.

- ^ Orchard 1997, p. 11.

- ^ a b Fee 2004, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Much 1926, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Birkhan 1974, p. 34.

- ^ Holthausen, Ferdinand (1948). Vergleichendes und Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altwestnordischen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- ^ a b c Kitson, Peter R. (2000). "Gawain/Gwalchmai and his Peers: Romance Heroes (and a Heroine) in England, the Celtic Lands, and the Continent". Nomina. 23: 149–166.

- ^ A. G. Brodeur's translation (New York: American-Scandinavian Foundation, 1916).

- ^ Dumézil 1970, p. 1178.

- ^ a b c Hostetter 1991, p. 6.

- ^ Falluomini 2017, p. 286.

- ^ Schuhmann, R., "A linguistic analysis of the Codex Bononiensis", in: Auer and De Vaan eds., Le palimpseste gotique de Bologne. Études philologiques et linguistiques / The Gothic Palimpsest from Bologna. Philological and Linguistic Studies (Lausanne 2016) pp. 55–72, relevant section at p. 56

- ^ Beechy 2010, p. 6.

- ^ Cross 1964, p. 74: "For the total evidence stresses that OE. earendel has an area of meaning which allows it to represent Latin words describing varying concepts of 'light'; and on occasions, (aurora, lucifer, dægrima) this area is limited to permit equation with words meaning: 'coming or rising light, beginning of light, bringer of light'. It would appear from discussions of the etymology of earendel that the more limited meaning is the original one, and the meanings attested in equations with OE. leoma and Latin jubar are later extensions."

- ^ Beechy 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Beechy 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Cook 1900, p. 5.

- ^ Raw, Barbara C. (1997). Trinity and Incarnation in Anglo-Saxon Art and Thought. Cambridge University Press. p. 75 n. 102. ISBN 978-0-521-55371-1.

- ^ Beechy 2010, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Cook 1900, pp. 88–91.

- ^ Cross 1964, p. 74: "In these explanations Oriens is seen to be the 'source of true light', 'the fount of light' and 'light (which) rises from the Orient'. In view therefore of the application of OE. earendel, the explanations of Latin oriens and the OE. poet's close attention to the Latin antiphon, it is reasonable to conclude that earendel was chosen as an equivalent of oriens."

- ^ Beechy 2010, pp. 2–3: "Eala earendel in Christ I, line 104, translates O Oriens from the Latin antiphon on which the Old English lyric is based."

- ^ Beechy, Tiffanya (2010b). The Poetics of Old English. Ashgate. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0-7546-6917-3.

- ^ Beechy 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Beechy 2010, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Morris 1880, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Cross 1964, pp. 72–74.

- ^ a b Beechy 2010, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c d Beechy 2010, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Milfull 1996, pp. 143, 173.

- ^ Beechy 2010, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Cross 1964, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Schade, Oskar (1882). Altdeutsches Wörterbuch. Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses. p. 667.

- ^ Grimm 1844, p. 348.

- ^ a b Gibbs & Johnson 2002, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Grimm 1844, p. 347.

- ^ Gerritsen, Willem P.; van Melle, A. G. (2000). A Dictionary of Medieval Heroes: Characters in Medieval Narrative Traditions and Their Afterlife in Literature, Theatre and the Visual Arts. Boydell & Brewer. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-85115-780-1.

- ^ Heinzel 1892, p. 14.

- ^ Fischer 2015, pp. 178–183.

- ^ Dumézil 1970, pp. 1176–1178.

- ^ Hostetter 1991, p. 5; see n. 4.

- ^ a b Tolkien 1981, p. 385.

- ^ a b Hostetter 1991, p. 7.

- ^ Welch, Brian; Coe, Dan; Diego, José M.; Zitrin, Adi; Zackrisson, Erik; Dimauro, Paola; et al. (March 2022). "A highly magnified star at redshift 6.2". Nature. 603 (7903): 815–818. arXiv:2209.14866. Bibcode:2022Natur.603..815W. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04449-y. PMID 35354998. S2CID 247842625.

- ^ Gianopoulos, Andrea (30 March 2022). "Record Broken: Hubble Spots Farthest Star Ever Seen" (Press release). NASA.

- ^ Zalutskiy, Artyom (10 July 2022). "Commitment to historical accuracy helps turn the Northman into a masterpiece". FilmDaze.

Bibliography

[edit]Primary sources:

- Cook, Albert S. (1900). The Christ of Cynewulf; a poem in three parts, The advent, The ascension, and The last judgment. Boston: Ginn & Company.

- Faulkes, Anthony (1987). Edda. Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3.

- Fischer, Peter (2015). Gesta Danorum. Vol. I. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820523-4.

- Milfull, Inge B. (1996). The Hymns of the Anglo-Saxon Church: A Study and Edition of the 'Durham Hymnal'. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46252-5.

- Morris, Richard (1880). The Blickling homilies of the tenth century: From the Marquis of Lothian's unique ms. A.D. 971. Early English Text Society. London: N. Trübner & Co.

Secondary sources:

- Beechy, Tiffany (2010). "Eala Earendel : Extraordinary Poetics in Old English". Modern Philology. 108 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1086/656221. ISSN 0026-8232. S2CID 163399025.

- Birkhan, Helmut (1974). "Irisches im "Orendel"?". Kurtrierisches Jahrbuch. 14: 33–45.

- Cross, J. E. (1964). "The 'Coeternal beam' in the O.E. advent poem (Christ I)ll.104–129". Neophilologus. 48 (1): 72–81. doi:10.1007/BF01515526. ISSN 1572-8668. S2CID 162245531.

- de Vries, Jan (1957). Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte. Vol. 2 (1970 ed.). Walter De Gruyter.

- de Vries, Jan (1962). Altnordisches Etymologisches Worterbuch (1977 ed.). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-05436-3.

- Dumézil, Georges (1970). "Horwendillus et Aurvandill". In Lévi-Strauss, Claude; Pouillon, Jean; Maranda, Pierre (eds.). Échanges et communications. De Gruyter. pp. 1171–1179. ISBN 978-3-11-169828-1.

- Falluomini, Carla (2017). "Zum gotischen Fragment aus Bologna II: Berichtigungen und neue Lesungen". Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und Literatur. 146 (3): 284–294. doi:10.3813/zfda-2017-0012. S2CID 217253695.

- Fee, Christopher R. (2004). Gods, Heroes, & Kings: The Battle for Mythic Britain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-029170-9.

- Gibbs, Marion; Johnson, Sidney M. (2002). Medieval German Literature: A Companion. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-95678-3.

- Grimm, Jacob (1844). Deutsche Mythologie. Göttingen: Dieterichsche Buchhandlung. pp. 347–349.

- Hatto, Arthur T. (1965). Eos: An enquiry into the theme of lovers' meetings and partings at dawn in poetry. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-170360-2.

- Heinzel, Richard (1892). Über das Gedicht vom König Orendel. F. Tempsky. Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien.

- Hostetter, Carl F. (1991). "Over Middle-earth Sent Unto Men: On the Philological Origins of Tolkien's Eärendel Myth". Mythlore. 17 (3 (65)): 5–10. ISSN 0146-9339. JSTOR 26812595.

- Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983969-8.

- Much, Rudolf (1926). "Wandalische Götter". Mitteilungen der schlesischen Gesellschaft für Volkskunde. 27: 20–41.

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-34520-5.

- Schröder, F. R. (1938). "Der Ursprung der Hamletsage". Germanisch-Romanische Monatsschrift. 26: 81–108.

- Simek, Rudolf (1984). Lexikon der germanischen Mythologie. A. Kröner. ISBN 978-3-520-36801-0.

- Ström, Åke V.; Biezais, Haralds (1975). Germanische und baltische Religion. Kohlhammer. ISBN 978-3-17-001157-1.

- Tolkien, J. R. R (1981). Carpenter, Humphrey (ed.). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Laistner, Ludwig (1894). "Der germanische Orendel". Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur. 38: 113–135. ISSN 0044-2518. JSTOR 20651106.

- Ker, W. P. (1897). "Notes on Orendel and Other Stories". Folklore. 8 (4): 289–307. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1897.9720426. ISSN 0015-587X. JSTOR 1253421.

- Much, Rudolf (1934). "Aurvandils tá". Festschrift H. Seger. Breslau.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tarcsay, Tibor (2015). "Chaoskampf, Salvation, and Dragons: Archetypes in Tolkien's Earendel". Mythlore. 33 (2): 139–150. ISSN 0146-9339.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch