Dewan Rakyat

House of Representatives Dewan Rakyat ديوان رعيت | |

|---|---|

| 15th Parliament | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Leadership | |

Deputy Speaker I | |

Deputy Speaker II | |

Nizam Mydin Bacha Mydin since 13 May 2020 | |

Deputy Prime Minister I | |

Deputy Prime Minister II | |

| Structure | |

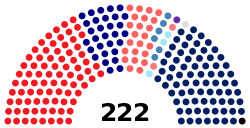

| Seats | 222 |

| |

Political groups | (As of 4 March 2025) Government (153) PH (81) BN (30) GPS (23) GRS (6)

WARISAN (3) KDM (2) Independent (7) Opposition (69) PN (68) |

| Committees | 5

|

Length of term | Up to 5 years |

| Elections | |

| First-past-the-post | |

Last election | 19 November 2022 |

Next election | By 17 February 2028 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Dewan Rakyat chamber Malaysian Houses of Parliament, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

The Dewan Rakyat (English: House of Representatives, lit. 'People's Assembly'; Jawi: ديوان رعيت), is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament, the federal legislature of Malaysia. The chamber and its powers are established by Article 44 of the Constitution of Malaysia. The Dewan Rakyat sits in the Houses of Parliament in Kuala Lumpur, along with the Dewan Negara, the upper house.

The Dewan Rakyat is a directly elected body consisting of 222 members known as Members of Parliament (MPs). Members are elected by first-past-the-post voting with one member from each federal constituency. Members hold their seats until the Dewan Rakyat is dissolved, the term of which is constitutionally limited to five years after an election. The number of seats each state or territory is entitled to is fixed by Article 46 of the Constitution.

While the concurrence of both chambers of Parliament is normally necessary for legislation to be enacted, the Dewan Rakyat holds significantly more power in practice; the Dewan Negara very rarely rejects bills that have been passed by the Dewan Rakyat and the Dewan Rakyat can bypass the Dewan Negara if it refuses to pass a specific law twice, with at least one year in between. The Cabinet is solely responsible to the Dewan Rakyat, and the prime minister only has to maintain the support of the lower house.

History

[edit]The history of the Dewan Rakyat can be traced back during the Federal Legislative Council era. At that time, 52 out of the 100-member council were elected directly by the people using first-past-the-post system, returning one representatives from each constituencies. The council was dissolved in 1959, a year ahead of its expiration term to pave the way for a new election for the new Dewan Rakyat, which was to be the lower house of the Parliament of Malaysia.

The voting system was retained from the previous election, and has since taken place in the subsequent elections post-independence. The number of seats increased to 104, abolishing the nominated seats in favour of elected members. The ruling Alliance returned as the Government with a majority of 44 seats. Tunku Abdul Rahman reelected as the Prime Minister, while the new Parliament convened on 2 September 1959.

After the formation of Malaysia, a special autonomy status allowing representatives from Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore to be elected indirectly by the state assemblies. Therefore, in 1964 elections, only 65% of the total seats were contested. The Alliance retained its position with a higher margin.

The 1969 elections marked the first time Alliance failed to win a supermajority and majority popular vote. The racial unrests resulted in the Parliament being suspended until 1971. Upon the reopening of the Parliament, the Alliance returned with a supermajority government after Bornean local parties, PAS and GERAKAN joined the coalition, later to be known as Barisan Nasional.

Membership

[edit]Members are referred to as "Member of Parliament" ("MPs") or "Ahli Dewan Rakyat" (lit. 'member of the Dewan Rakyat') in Malay. The term of office is as long as the member wins in the elections.

A member of the Dewan Rakyat must be at least 18 years of age, which was lowered from 21 when the Dewan Rakyat passed the Bill to amend Article 47[1] of the Federal Constitution in 2019,[2] and must not concurrently be a member of the Dewan Negara. The presiding officer of the Dewan Rakyat is the Speaker, who is elected at the beginning of each Parliament or after the vacation of the post, by the MPs. Two Deputy Speakers are also elected, and one of them sits in place of the Speaker when he is absent. The Dewan Rakyat machinery is supervised by the Clerk of the House who is appointed by the King; he may only be removed from office through the manner prescribed for judges or by mandatory retirement at age 60.[3]

As of the 2018 general election, the Dewan Rakyat has 222 elected members. Members are elected from federal constituencies drawn by the Election Commission. Constituency boundaries are redrawn every ten years based on the latest census.

Each Dewan Rakyat lasts for a maximum of five years, after which a general election must be called. In the general election, voters select a candidate to represent their constituency in the Dewan Rakyat. The first-past-the-post voting system is used; the candidate who gains the most votes wins the seat.

Before a general election can be called, the King must first dissolve Parliament on the advice of the Prime Minister.[3] According to the Constitution, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong has the right at his own discretion to either grant or withhold consent to dissolve the parliament.

Powers and procedure

[edit]Parliament is the legislative branch of the federal government and is responsible for passing, amending and repealing primary legislation. These are known as Acts of Parliament.

Members of Parliament possess parliamentary privilege and are permitted to speak on any subject without fear of censure outside Parliament; the only body that can censure an MP is the House Committee of Privileges. Immunity is effective from the moment a member of Parliament is sworn in, and only applies when that member has the floor; it does not apply to statements made outside the House. An exception is made by the Sedition Act passed by Parliament in the wake of the 13 May racial riots in 1969. Under the Act, all public discussion of repealing certain Articles of the Constitution dealing with Bumiputra privileges such as Article 153 is illegal. This prohibition is extended to all members of both houses of Parliament.[4] Members of Parliament are also forbidden from criticising the King and judges.[5]

The executive government, comprising the Prime Minister and his Cabinet, is usually drawn from members of Parliament; most of its members are typically members of the Dewan Rakyat. After a general election or the resignation or death of a Prime Minister, the King selects the Prime Minister, who is the head of government but constitutionally subordinate to him, from the Dewan Rakyat. In practice, this is usually the leader of the largest party in Parliament. The Prime Minister then submits a list containing the names of members of his Cabinet, who will then be appointed as Ministers by the King. Members of the Cabinet must also be members of Parliament. If the Prime Minister loses the confidence of the Dewan Rakyat, whether by losing a no-confidence vote or failing to pass a budget, he must either advise the King to dissolve Parliament and hold a general election or submit his resignation to the King. The King has the discretion to grant or withhold consent to the dissolution. If consent is withheld, the government must resign and the King would appoint a new Prime Minister that has the support of the majority of members of Parliament. The Cabinet formulates government policy and drafts bills, meeting in private. Its members must accept "collective responsibility" for the decisions the Cabinet makes, even if some members disagree with it; if they do not wish to be held responsible for Cabinet decisions, they must resign. Although the Constitution makes no provision for it, there is also a Deputy Prime Minister, who is the de facto successor of the Prime Minister should he die or be otherwise incapacitated.[6]

A proposed act of law begins its life when a particular government minister or ministry prepares a first draft with the assistance of the Attorney-General's Department. The draft, known as a bill, is then discussed by the Cabinet. If it is agreed to submit it to Parliament, the bill is distributed to all MPs. It then goes through three readings before the Dewan Rakyat. The first reading is where the minister or his deputy submits it to Parliament. At the second reading, the bill is discussed and debated by MPs. At the third reading, the minister or his deputy formally submit it to a vote for approval. A simple majority is usually required to pass the bill, but in certain cases, such as amendments to the constitution, a two-thirds majority is required. Should the bill pass, it is sent to the Dewan Negara, where the three readings are carried out again. The Dewan Negara may choose not to pass the bill, but this only delays its passage by a month, or in some cases, a year; once this period expires, the bill is considered to have been passed by the house.[7]

If the bill passes, it is presented to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong who has 30 days to consider the bill. Should he disagree with it, he returns it to Parliament with a list of suggested amendments. Parliament must then reconsider the bill and its proposed amendments and return it to the King within 30 days if they pass it again. The King then has another 30 days to give the royal assent; otherwise, it passes into law. The law does not take effect until it is published in the Government Gazette.[8]

The government attempts to maintain top secrecy regarding bills debated; MPs generally receive copies of bills only a few days before they are debated, and newspapers are rarely provided with copies of the bills before they are debated. In some cases, such as a 1968 amendment to the Constitution, an MP may be presented with a bill to be debated on the same day it is tabled, and all three readings may be carried out that day itself.[9] In rare circumstances, the government may release a White paper containing particular proposals that will eventually be incorporated into a bill; this has been done for legislation such as the Universities and University Colleges Act.[10]

Although the process above assumes only the government can propose bills, there also exists a process for private member's bills. However, unlike most other legislatures following the Westminster system, few members of Parliament actually introduce bills.[11] To present a private member's bill, the member in question must seek the leave of the House in question to debate the bill before it is moved. Originally, it was allowed to debate the bill in the process of seeking leave, but this process was discontinued by an amendment to the Standing Orders of the Dewan Rakyat.[12] It is also possible for members of the Dewan Negara to initiate bills; however, only cabinet ministers are permitted to move finance-related bills, which must be tabled in the Dewan Rakyat.[13]

It is often alleged that legislation proposed by the opposition parties, which must naturally be in the form of a private member's bill, is not seriously considered by Parliament. Some have gone as far as to claim that the rights of members of Parliament to debate proposed bills have been severely curtailed by incidents such as an amendment of the Standing Orders that permitted the Speaker to amend written copies of MPs' speeches before they were made. Nevertheless, it is admitted by some of these critics that "government officials often face sharp questioning in Parliament, although this is not always reported in detail in the press."[14]

Special Chamber

[edit]In 2016, Speaker Pandikar Amin Mulia introduced a Special Chamber of the Dewan Rakyat which holds proceedings separately from the main house, to "allow matters of national importance or urgency to be discussed without interrupting the normal proceedings of the Lower House."[15] Government and opposition leaders both welcomed the move, with Minister in the Prime Minister's Department Azalina Othman Said, Democratic Action Party whip Anthony Loke, and People's Justice Party whip Johari Abdul issuing favourable statements to the press.[15] Amendments to the Standing Orders of the Dewan Rakyat in April 2016 established the Special Chamber to host debates on "any matter of administration for which the government is responsible" or "a defined matter of urgent public importance".[16]

Liew Chin Tong, at the time an opposition Member of Parliament, claimed he had lobbied Pandikar to institute the Special Chamber, which he has said takes inspiration from both the Australian and British parliaments. Liew has proposed expanding the remit of the Special Chamber: "A full-fledged second chamber should take away all constituency-specific issues off the main chamber and move them to the second chamber so that the main chamber focuses only on the most important things."[17] When he and Pandikar spoke at a panel on parliamentary reform in 2021, Liew also proposed expanding the amount of time allotted for Special Chamber debates: "Currently, only two speeches of seven and a half minutes each by backbenchers or opposition MPs with replies from government of equal time are permitted, amounting to only 30 minutes each day."[18]

In 2023, after being elected Speaker of the Dewan Rakyat, Johari announced that the Special Chamber would double the number of motions permitted per session from two to four. He also announced that opposition and government backbencher MPs would be allowed to preside over the Special Chamber, instead of limiting the chair to just the Speaker and Deputy Speakers.[19]

Current composition

[edit] | |||||

| Affiliation | Leader in Parliament | Status | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 election | Current | ||||

| Pakatan Harapan | Anwar Ibrahim | Majority coalition government | 81 | 81 | |

| Barisan Nasional | Ahmad Zahid Hamidi | 30 | 30 | ||

| Gabungan Parti Sarawak | Fadillah Yusof | 23 | 23 | ||

| Gabungan Rakyat Sabah | Jeffrey Kitingan | 6 | 6 | ||

| Heritage Party | Shafie Apdal | 3 | 3 | ||

| Social Democratic Harmony Party | Wetrom Bahanda | 2 | 2 | ||

| Parti Bangsa Malaysia | Larry Sng | 1 | 1 | ||

| Independent | Verdon Bahanda, Iskandar Dzulkarnain Abdul Khalid, Suhaili Abdul Rahman, Mohd Azizi Abu Naim, Zahari Kechik, Syed Abu Hussin Hafiz and Zulkafperi Hanapi | 1 | 7 | ||

| Perikatan Nasional | Muhyiddin Yassin | Opposition | 74 | 68 | |

| Malaysian United Democratic Alliance | Syed Saddiq Syed Abdul Rahman | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 222 | 222 | |||

Members per state and federal territory

[edit]| State / federal territory | Number of seats | Population (2020 census) | Population per seat |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 1,982,112 | 180,192 | |

| 1 | 95,120 | 95,120 | |

| 1 | 109,202 | 109,202 | |

| 26 | 4,009,670 | 154,218 | |

| 15 | 2,131,427 | 142,095 | |

| 14 | 1,792,501 | 128,036 | |

| 6 | 998,428 | 166,405 | |

| 8 | 1,199,974 | 149,997 | |

| 14 | 1,591,295 | 113,664 | |

| 13 | 1,740,405 | 133,877 | |

| 24 | 2,496,041 | 104,002 | |

| 3 | 284,885 | 94,962 | |

| 25 | 3,418,785 | 136,751 | |

| 31 | 2,453,677 | 79,151 | |

| 22 | 6,994,423 | 317,928 | |

| 8 | 1,149,440 | 143,680 |

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "Constitution (Amendment) Act 2019" (PDF).

- ^ Correspondent, Trinna LeongMalaysia (16 July 2019). "Malaysia's MPs approve amendment to lower voting age from 21 to 18". The Straits Times. ISSN 0585-3923. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b "Government: Parliament: Dewan Rakyat". Retrieved 8 February 2006. Archived 14 June 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Means, Gordon P. (1991). Malaysian Politics: The Second Generation, pp. 14, 15. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-588988-6.

- ^ Myytenaere, Robert (1998). "The Immunities of Members of Parliament" Archived 25 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ "Branches of Government in Malaysia" Archived 7 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 3 February 2006.

- ^ Shuid, Mahdi & Yunus, Mohd. Fauzi (2001). Malaysian Studies, pp. 33, 34. Longman. ISBN 983-74-2024-3.

- ^ Shuid & Yunus, p. 34.

- ^ Tan, Chee Koon & Vasil, Raj (ed., 1984). Without Fear or Favour, p. 7. Eastern Universities Press. ISBN 967-908-051-X.

- ^ Tan & Vasil, p. 11.

- ^ Ram, B. Suresh (16 December 2005). "Pro-people, passionate politician" Archived 27 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine. The Sun.

- ^ Lim, Kit Siang (1997). "Consensus Against Corruption". Retrieved 11 February 2006.

- ^ Henderson, John William, Vreeland, Nena, Dana, Glenn B., Hurwitz, Geoffrey B., Just, Peter, Moeller, Philip W. & Shinn, R.S. (1977). Area Handbook for Malaysia, p. 219. American University, Washington D.C., Foreign Area Studies. LCCN 771294.

- ^ "Malaysia". Retrieved 22 January 2006.

- ^ a b Kumar, Kamles (16 May 2016). "Parliament convenes Special Chamber for first time". Malay Mail. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Hassan, Hafiz (20 July 2021). "LETTER | Is the special sitting of Parliament a sitting of special chamber?". Malaysiakini. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Liew, Chin Tong (27 November 2019). "Let's speed up the remaking of our parliament - Liew Chin Tong". liewchintong.com. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Liew, Chin Tong (8 September 2021). "Key agenda for parliamentary reform - Liew Chin Tong". liewchintong.com. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "PMQ pilot test to start next week". The Star. 9 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch