Human

| Human | |

|---|---|

| |

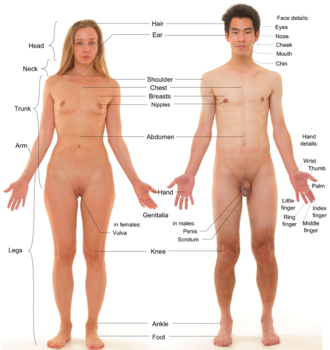

| Male (left) and female (right) adult humans | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | H. sapiens |

| Binomial name | |

| Homo sapiens | |

| |

| Homo sapiens population density (2020) | |

Humans (Homo sapiens) or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus Homo. They are great apes characterized by their hairlessness, bipedalism, and high intelligence. Humans have large brains, enabling more advanced cognitive skills that facilitate successful adaptation to varied environments, development of sophisticated tools, and formation of complex social structures and civilizations.

Humans are highly social, with individual humans tending to belong to a multi-layered network of distinct social groups — from families and peer groups to corporations and political states. As such, social interactions between humans have established a wide variety of values, social norms, languages, and traditions (collectively termed institutions), each of which bolsters human society. Humans are also highly curious: the desire to understand and influence phenomena has motivated humanity's development of science, technology, philosophy, mythology, religion, and other frameworks of knowledge; humans also study themselves through such domains as anthropology, social science, history, psychology, and medicine. As of 2025, there are estimated to be more than 8 billion humans alive.

For most of their history, humans were nomadic hunter-gatherers. Humans began exhibiting behavioral modernity about 160,000–60,000 years ago. The Neolithic Revolution occurred independently in multiple locations, the earliest in Southwest Asia 13,000 years ago, and saw the emergence of agriculture and permanent human settlement; in turn, this led to the development of civilization and kickstarted a period of continuous (and ongoing) population growth and rapid technological change. Since then, a number of civilizations have risen and fallen, while a number of sociocultural and technological developments have resulted in significant changes to the human lifestyle.

Although the term "humans" technically equates with all members of the genus Homo, in common usage it generally refers to Homo sapiens, the only extant member. All other members of the genus Homo, which are now extinct, are known as archaic humans, and the term "modern human" is used to distinguish Homo sapiens from archaic humans. Anatomically modern humans emerged around 300,000 years ago in Africa, evolving from Homo heidelbergensis or a similar species. Migrating out of Africa, they gradually replaced and interbred with local populations of archaic humans. Multiple hypotheses for the extinction of archaic human species such as Neanderthals include competition, violence, interbreeding with Homo sapiens, or inability to adapt to climate change. Genes and the environment influence human biological variation in visible characteristics, physiology, disease susceptibility, mental abilities, body size, and life span. Though humans vary in many traits (such as genetic predispositions and physical features), humans are among the least genetically diverse primates. Any two humans are at least 99% genetically similar. Humans are sexually dimorphic: generally, males have greater body strength and females have a higher body fat percentage. At puberty, humans develop secondary sex characteristics. Females are capable of pregnancy, usually between puberty, at around 12 years old, and menopause, around the age of 50.

Humans are omnivorous, capable of consuming a wide variety of plant and animal material, and have used fire and other forms of heat to prepare and cook food since the time of Homo erectus. Humans have had a dramatic effect on the environment. They are apex predators, being rarely preyed upon by other species.[1] Human population growth, industrialization, land development, overconsumption and combustion of fossil fuels have led to environmental destruction and pollution that significantly contributes to the ongoing mass extinction of other forms of life.[2][3] Within the last century, humans have explored challenging environments such as Antarctica, the deep sea, and outer space, though human habitation in these environments is typically limited in duration and restricted to scientific, military, or industrial expeditions. Humans have visited the Moon and sent human-made spacecraft to other celestial bodies. Humans can survive for up to eight weeks without food and several days without water. Humans are generally diurnal, sleeping on average seven to nine hours per day. Childbirth is dangerous, with a high risk of complications and death. Often, both the mother and the father provide care for their children, who are helpless at birth.

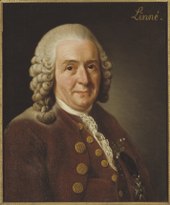

Etymology and definition

All modern humans are classified into the species Homo sapiens, coined by Carl Linnaeus in his 1735 work Systema Naturae.[4] The generic name Homo is a learned 18th-century derivation from Latin homō, which refers to humans of either sex.[5][6] The word human can refer to all members of the Homo genus.[7] The name Homo sapiens means 'wise man' or 'knowledgeable man'.[8] There is disagreement if certain extinct members of the genus, namely Neanderthals, should be included as a separate species of humans or as a subspecies of H. sapiens.[7]

Human is a loanword of Middle English from Old French humain, ultimately from Latin hūmānus, the adjectival form of homō ('man' — in the sense of humanity).[9] The native English term man can refer to the species generally (a synonym for humanity) as well as to human males. It may also refer to individuals of either sex.[10]

Despite the fact that the word animal is colloquially used as an antonym for human,[11] and contrary to a common biological misconception, humans are animals.[12] The word person is often used interchangeably with human, but philosophical debate exists as to whether personhood applies to all humans or all sentient beings, and further if a human can lose personhood (such as by going into a persistent vegetative state).[13]

Evolution

Humans are apes (superfamily Hominoidea).[14] The lineage of apes that eventually gave rise to humans first split from gibbons (family Hylobatidae), next orangutans (genus Pongo), then gorillas (genus Gorilla), and finally, chimpanzees and bonobos (genus Pan). The last split, between the human and chimpanzee–bonobo lineages, took place around 8–4 million years ago, in the late Miocene epoch.[15][16] During this split, chromosome 2 was formed from the joining of two other chromosomes, leaving humans with only 23 pairs of chromosomes, compared to 24 for the other apes.[17] Following their split with chimpanzees and bonobos, the hominins diversified into many species and at least two distinct genera. All but one of these lineages — representing the genus Homo and its sole extant species Homo sapiens — are now extinct.[18]

The genus Homo evolved from Australopithecus.[19][20] Though fossils from the transition are scarce, the earliest members of Homo share several key traits with Australopithecus.[21][22]

Some specialists claim Homo appeared 4.30–2.56 million years ago.[23] Studies found that Ardipithecus ramidus was in some aspects closer to humans than to apes.[24][25][26][27] Stone tools were used by Australopithecus afarensis around 3.3 million years ago.[28] Others think it did not happen before 1.9 millions years ago, because Homo habilis is not a part of Homo.[29] The earliest record of Homo is the 2.8 million-year-old specimen LD 350-1 from Ethiopia, and the earliest named species are Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensis which evolved by 2.3 million years ago.[22] H. erectus (the African variant is sometimes called H. ergaster) evolved 2 million years ago and was the first archaic human species to leave Africa and disperse across Eurasia.[30] H. erectus also was the first to evolve a characteristically human body plan. Homo sapiens emerged in Africa around 300,000 years ago from a species commonly designated as either H. heidelbergensis or H. rhodesiensis, the descendants of H. erectus that remained in Africa.[31] H. sapiens migrated out of the continent, gradually replacing or interbreeding with local populations of archaic humans.[32][33][34] Humans began exhibiting behavioral modernity about 160,000–70,000 years ago,[35] and possibly earlier.[36] This development was likely selected amidst natural climate change in Middle to Late Pleistocene Africa.[37]

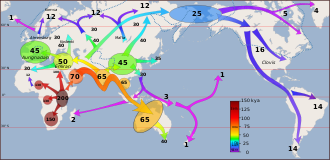

The "out of Africa" migration took place in at least two waves, the first around 130,000 to 100,000 years ago, the second (Southern Dispersal) around 70,000 to 50,000 years ago.[38][39] H. sapiens proceeded to colonize all the continents and larger islands, arriving in Eurasia 125,000 years ago,[40][41] Australia around 65,000 years ago,[42] the Americas around 15,000 years ago, and remote islands such as Hawaii, Easter Island, Madagascar, and New Zealand in the years 300 to 1280 CE.[43][44]

Human evolution was not a simple linear or branched progression but involved interbreeding between related species.[45][46][47] Genomic research has shown that hybridization between substantially diverged lineages was common in human evolution.[48] DNA evidence suggests that several genes of Neanderthal origin are present among all non sub-Saharan-African populations, and Neanderthals and other hominins, such as Denisovans, may have contributed up to 6% of their genome to present-day non sub-Saharan-African humans.[45][49][50]

Human evolution is characterized by a number of morphological, developmental, physiological, and behavioral changes that have taken place since the split between the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. The most significant of these adaptations are hairlessness,[51] obligate bipedalism, increased brain size and decreased sexual dimorphism (neoteny). The relationship between all these changes is the subject of ongoing debate.[52]

| Hominoidea (hominoids, apes) | |

History

Prehistory

Until about 12,000 years ago, all humans lived as hunter-gatherers.[53][54] The Neolithic Revolution (the invention of agriculture) first took place in Southwest Asia and spread through large parts of the Old World over the following millennia.[55] It also occurred independently in Mesoamerica (about 6,000 years ago),[56] China,[57][58] Papua New Guinea,[59] and the Sahel and West Savanna regions of Africa.[60][61][62]

Access to food surplus led to the formation of permanent human settlements, the domestication of animals and the use of metal tools for the first time in history. Agriculture and sedentary lifestyle led to the emergence of early civilizations.[63][64][65]

Ancient

An urban revolution took place in the 4th millennium BCE with the development of city-states, particularly Sumerian cities located in Mesopotamia.[66] It was in these cities that the earliest known form of writing, cuneiform script, appeared around 3000 BCE.[67] Other major civilizations to develop around this time were Ancient Egypt and the Indus Valley Civilisation.[68] They eventually traded with each other and invented technology such as wheels, plows and sails.[69][70][71][72] Emerging by 3000 BCE, the Caral–Supe civilization is the oldest complex civilization in the Americas.[73] Astronomy and mathematics were also developed and the Great Pyramid of Giza was built.[74][75][76] There is evidence of a severe drought lasting about a hundred years that may have caused the decline of these civilizations,[77] with new ones appearing in the aftermath. Babylonians came to dominate Mesopotamia while others,[78] such as the Poverty Point culture, Minoans and the Shang dynasty, rose to prominence in new areas.[79][80][81] The Late Bronze Age collapse around 1200 BCE resulted in the disappearance of a number of civilizations and the beginning of the Greek Dark Ages.[82][83] During this period iron started replacing bronze, leading to the Iron Age.[84]

In the 5th century BCE, history started being recorded as a discipline, which provided a much clearer picture of life at the time.[85] Between the 8th and 6th century BCE, Europe entered the classical antiquity age, a period when ancient Greece and ancient Rome flourished.[86][87] Around this time other civilizations also came to prominence. The Maya civilization started to build cities and create complex calendars.[88][89] In Africa, the Kingdom of Aksum overtook the declining Kingdom of Kush and facilitated trade between India and the Mediterranean.[90] In West Asia, the Achaemenid Empire's system of centralized governance became the precursor to many later empires,[91] while the Gupta Empire in India and the Han dynasty in China have been described as golden ages in their respective regions.[92][93]

Medieval

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, Europe entered the Middle Ages.[94] During this period, Christianity and the Church would provide centralized authority and education.[95] In the Middle East, Islam became the prominent religion and expanded into North Africa. It led to an Islamic Golden Age, inspiring achievements in architecture, the revival of old advances in science and technology, and the formation of a distinct way of life.[96][97] The Christian and Islamic worlds would eventually clash, with the Kingdom of England, the Kingdom of France and the Holy Roman Empire declaring a series of holy wars to regain control of the Holy Land from Muslims.[98]

In the Americas, between 200 and 900 CE Mesoamerica was in its Classic Period,[99] while further north, complex Mississippian societies would arise starting around 800 CE.[100] The Mongol Empire would conquer much of Eurasia in the 13th and 14th centuries.[101] Over this same time period, the Mali Empire in Africa grew to be the largest empire on the continent, stretching from Senegambia to Ivory Coast.[102] Oceania would see the rise of the Tuʻi Tonga Empire which expanded across many islands in the South Pacific.[103] By the late 15th century, the Aztecs and Inca had become the dominant power in Mesoamerica and the Andes, respectively.[104]

Modern

The early modern period in Europe and the Near East (c. 1450–1800) began with the final defeat of the Byzantine Empire, and the rise of the Ottoman Empire.[105] Meanwhile, Japan entered the Edo period,[106] the Qing dynasty rose in China[107] and the Mughal Empire ruled much of India.[108] Europe underwent the Renaissance, starting in the 15th century,[109] and the Age of Discovery began with the exploring and colonizing of new regions.[110] This included the colonization of the Americas[111] and the Columbian Exchange.[112] This expansion led to the Atlantic slave trade[113] and the genocide of the Americas' indigenous peoples.[114] This period also marked the Scientific Revolution, with great advances in mathematics, mechanics, astronomy and physiology.[115]

The late modern period (1800–present) saw the Technological and Industrial Revolution bring such discoveries as imaging technology, major innovations in transport and energy development.[116] Influenced by Enlightenment ideals, the Americas and Europe experienced a period of political revolutions known as the Age of Revolution.[117] The Napoleonic Wars raged through Europe in the early 1800s,[118] Spain lost most of its colonies in the New World,[119] while Europeans continued expansion into Africa – where European control went from 10% to almost 90% in less than 50 years[120] – and Oceania.[121] In the 19th century, the British Empire expanded to become the world's largest empire.[122]

A tenuous balance of power among European nations collapsed in 1914 with the outbreak of the First World War, one of the deadliest conflicts in history.[123] In the 1930s, a worldwide economic crisis led to the rise of authoritarian regimes and a Second World War, involving almost all of the world's countries.[124] The war's destruction led to the collapse of most global empires, leading to widespread decolonization.

Following the conclusion of the Second World War in 1945, the United States[125] and the Soviet Union emerged as the remaining global superpowers. This led to a Cold War that saw a struggle for global influence, including a nuclear arms race and a space race, ending in the collapse of the Soviet Union.[126][127] The current Information Age, spurred by the development of the Internet and artificial intelligence systems, sees the world becoming increasingly globalized and interconnected.[128]

Habitat and population

| |

| World population | 8.1 billion |

|---|---|

| Population density | 16/km2 (41/sq mi) by total area 55/km2 (142/sq mi) by land area |

| Largest cities[n 2] | Tokyo, Delhi, Shanghai, São Paulo, Mexico City, Cairo, Mumbai, Beijing, Dhaka, Osaka |

Early human settlements were dependent on proximity to water and – depending on the lifestyle – other natural resources used for subsistence, such as populations of animal prey for hunting and arable land for growing crops and grazing livestock.[132] Modern humans, however, have a great capacity for altering their habitats by means of technology, irrigation, urban planning, construction, deforestation and desertification.[133] Human settlements continue to be vulnerable to natural disasters, especially those placed in hazardous locations and with low quality of construction.[134] Grouping and deliberate habitat alteration is often done with the goals of providing protection, accumulating comforts or material wealth, expanding the available food, improving aesthetics, increasing knowledge or enhancing the exchange of resources.[135]

Humans are one of the most adaptable species, despite having a low or narrow tolerance for many of the earth's extreme environments.[136] Currently the species is present in all eight biogeographical realms, although their presence in the Antarctic realm is very limited to research stations and annually there is a population decline in the winter months of this realm. Humans established nation-states in the other seven realms, such as South Africa, India, Russia, Australia, Fiji, the United States, and Brazil (each located in a different biogeographical realm).

Within the last century, humans have also explored the deep sea and outer space. Human habitation within these hostile environments is restrictive and expensive, typically limited in duration, and restricted to scientific, military, or industrial expeditions.[137] Humans have visited the Moon and made their presence known on other celestial bodies through human-made robotic spacecraft.[138][139][140] Since 2000, there has been continuous human presence in space through habitation on the International Space Station.[141]

By using advanced tools and clothing, humans have been able to extend their tolerance to a wide variety of temperatures, humidities, and altitudes.[136][142] As a result, humans are a cosmopolitan species found in almost all regions of the world, including tropical rainforest, arid desert, extremely cold arctic regions, and heavily polluted cities; in comparison, most other species are confined to a few geographical areas by their limited adaptability.[143] The human population is not, however, uniformly distributed on the Earth's surface, because the population density varies from one region to another, and large stretches of surface are almost completely uninhabited, like Antarctica and vast swathes of the ocean.[136][144] Most humans (61%) live in Asia; the remainder live in the Americas (14%), Africa (14%), Europe (11%), and Oceania (0.5%).[145]

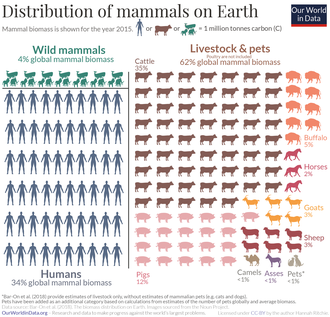

Estimates of the population at the time agriculture emerged in around 10,000 BC have ranged between 1 million and 15 million.[147][148] Around 50–60 million people lived in the combined eastern and western Roman Empire in the 4th century AD.[149] Bubonic plagues, first recorded in the 6th century AD, reduced the population by 50%, with the Black Death killing 75–200 million people in Eurasia and North Africa alone.[150] Human population is believed to have reached one billion in 1800. It has since then increased exponentially, reaching two billion in 1930 and three billion in 1960, four in 1975, five in 1987 and six billion in 1999.[151] It passed seven billion in 2011[152] and passed eight billion in November 2022.[153] It took over two million years of human prehistory and history for the human population to reach one billion and only 207 years more to grow to 7 billion.[154] The combined biomass of the carbon of all the humans on Earth in 2018 was estimated at 60 million tons, about 10 times larger than that of all non-domesticated mammals.[146]

In 2018, 4.2 billion humans (55%) lived in urban areas, up from 751 million in 1950.[155] The most urbanized regions are Northern America (82%), Latin America (81%), Europe (74%) and Oceania (68%), with Africa and Asia having nearly 90% of the world's 3.4 billion rural population.[155] Problems for humans living in cities include various forms of pollution and crime,[156] especially in inner city and suburban slums.

Biology

Anatomy and physiology

Most aspects of human physiology are closely homologous to corresponding aspects of animal physiology. The dental formula of humans is: 2.1.2.32.1.2.3. Humans have proportionately shorter palates and much smaller teeth than other primates. They are the only primates to have short, relatively flush canine teeth. Humans have characteristically crowded teeth, with gaps from lost teeth usually closing up quickly in young individuals. Humans are gradually losing their third molars, with some individuals having them congenitally absent.[157]

Humans share with chimpanzees a vestigial tail,[158] appendix, flexible shoulder joints, grasping fingers and opposable thumbs.[159] Humans also have a more barrel-shaped chests in contrast to the funnel shape of other apes, an adaptation for bipedal respiration.[160] Apart from bipedalism and brain size, humans differ from chimpanzees mostly in smelling, hearing and digesting proteins.[161] While humans have a density of hair follicles comparable to other apes, it is predominantly vellus hair, most of which is so short and wispy as to be practically invisible.[162][163] Humans have about 2 million sweat glands spread over their entire bodies, many more than chimpanzees, whose sweat glands are scarce and are mainly located on the palm of the hand and on the soles of the feet.[164]

It is estimated that the worldwide average height for an adult human male is about 171 cm (5 ft 7 in), while the worldwide average height for adult human females is about 159 cm (5 ft 3 in).[165] Shrinkage of stature may begin in middle age in some individuals but tends to be typical in the extremely aged.[166] Throughout history, human populations have universally become taller, probably as a consequence of better nutrition, healthcare, and living conditions.[167] The average mass of an adult human is 59 kg (130 lb) for females and 77 kg (170 lb) for males.[168][169] Like many other conditions, body weight and body type are influenced by both genetic susceptibility and environment and varies greatly among individuals.[170][171]

Humans have a far faster and more accurate throw than other animals.[172] Humans are also among the best long-distance runners in the animal kingdom, but slower over short distances.[173][161] Humans' thinner body hair and more productive sweat glands help avoid heat exhaustion while running for long distances.[174] Compared to other apes, the human heart produces greater stroke volume and cardiac output and the aorta is proportionately larger.[175][176]

Genetics

Like most animals, humans are a diploid and eukaryotic species. Each somatic cell has two sets of 23 chromosomes, each set received from one parent; gametes have only one set of chromosomes, which is a mixture of the two parental sets. Among the 23 pairs of chromosomes, there are 22 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes. Like other mammals, humans have an XY sex-determination system, so that females have the sex chromosomes XX and males have XY.[177] Genes and environment influence human biological variation in visible characteristics, physiology, disease susceptibility and mental abilities. The exact influence of genes and environment on certain traits is not well understood.[178][179]

While no humans – not even monozygotic twins – are genetically identical,[180] two humans on average will have a genetic similarity of 99.5%-99.9%.[181][182] This makes them more homogeneous than other great apes, including chimpanzees.[183][184] This small variation in human DNA compared to many other species suggests a population bottleneck during the Late Pleistocene (around 100,000 years ago), in which the human population was reduced to a small number of breeding pairs.[185][186] The forces of natural selection have continued to operate on human populations, with evidence that certain regions of the genome display directional selection in the past 15,000 years.[187]

The human genome was first sequenced in 2001[188] and by 2020 hundreds of thousands of genomes had been sequenced.[189] In 2012 the International HapMap Project had compared the genomes of 1,184 individuals from 11 populations and identified 1.6 million single nucleotide polymorphisms.[190] African populations harbor the highest number of private genetic variants. While many of the common variants found in populations outside of Africa are also found on the African continent, there are still large numbers that are private to these regions, especially Oceania and the Americas.[191] By 2010 estimates, humans have approximately 22,000 genes.[192] By comparing mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited only from the mother, geneticists have concluded that the last female common ancestor whose genetic marker is found in all modern humans, the so-called mitochondrial Eve, must have lived around 90,000 to 200,000 years ago.[193][194][195][196]

Life cycle

Most human reproduction takes place by internal fertilization via sexual intercourse, but can also occur through assisted reproductive technology procedures.[197] The average gestation period is 38 weeks, but a normal pregnancy can vary by up to 37 days.[198] Embryonic development in the human covers the first eight weeks of development; at the beginning of the ninth week the embryo is termed a fetus.[199] Humans are able to induce early labor or perform a caesarean section if the child needs to be born earlier for medical reasons.[200] In developed countries, infants are typically 3–4 kg (7–9 lb) in weight and 47–53 cm (19–21 in) in height at birth.[201][202] However, low birth weight is common in developing countries, and contributes to the high levels of infant mortality in these regions.[203]

Compared with other species, human childbirth is dangerous, with a much higher risk of complications and death.[204] The size of the fetus's head is more closely matched to the pelvis than in other primates.[205] The reason for this is not completely understood,[n 3] but it contributes to a painful labor that can last 24 hours or more.[207] The chances of a successful labor increased significantly during the 20th century in wealthier countries with the advent of new medical technologies. In contrast, pregnancy and natural childbirth remain hazardous ordeals in developing regions of the world, with maternal death rates approximately 100 times greater than in developed countries.[208]

Both the mother and the father provide care for human offspring, in contrast to other primates, where parental care is mostly done by the mother.[209] Helpless at birth, humans continue to grow for some years, typically reaching sexual maturity at 15 to 17 years of age.[210][211][212] The human life span has been split into various stages ranging from three to twelve. Common stages include infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood and old age.[213] The lengths of these stages have varied across cultures and time periods but is typified by an unusually rapid growth spurt during adolescence.[214] Human females undergo menopause and become infertile at around the age of 50.[215] It has been proposed that menopause increases a woman's overall reproductive success by allowing her to invest more time and resources in her existing offspring, and in turn their children (the grandmother hypothesis), rather than by continuing to bear children into old age.[216][217]

The life span of an individual depends on two major factors, genetics and lifestyle choices.[218] For various reasons, including biological/genetic causes, women live on average about four years longer than men.[219] As of 2018[update], the global average life expectancy at birth of a girl is estimated to be 74.9 years compared to 70.4 for a boy.[220][221] There are significant geographical variations in human life expectancy, mostly correlated with economic development – for example, life expectancy at birth in Hong Kong is 87.6 years for girls and 81.8 for boys, while in the Central African Republic, it is 55.0 years for girls and 50.6 for boys.[222][223] The developed world is generally aging, with the median age around 40 years. In the developing world, the median age is between 15 and 20 years. While one in five Europeans is 60 years of age or older, only one in twenty Africans is 60 years of age or older.[224] In 2012, the United Nations estimated that there were 316,600 living centenarians (humans of age 100 or older) worldwide.[225]

|  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |

| Infant boy and girl | Boy and girl before puberty (children) | Adolescent male and female | Adult man and woman | Elderly man and woman |

|---|

Diet

Humans are omnivorous,[226] capable of consuming a wide variety of plant and animal material.[227][228] Human groups have adopted a range of diets from purely vegan to primarily carnivorous. In some cases, dietary restrictions in humans can lead to deficiency diseases; however, stable human groups have adapted to many dietary patterns through both genetic specialization and cultural conventions to use nutritionally balanced food sources.[229] The human diet is prominently reflected in human culture and has led to the development of food science.[230]

Until the development of agriculture, Homo sapiens employed a hunter-gatherer method as their sole means of food collection.[230] This involved combining stationary food sources (such as fruits, grains, tubers, and mushrooms, insect larvae and aquatic mollusks) with wild game, which must be hunted and captured in order to be consumed.[231] It has been proposed that humans have used fire to prepare and cook food since the time of Homo erectus.[232] Human domestication of wild plants began about 11,700 years ago, leading to the development of agriculture,[233] a gradual process called the Neolithic Revolution.[234] These dietary changes may also have altered human biology; the spread of dairy farming provided a new and rich source of food, leading to the evolution of the ability to digest lactose in some adults.[235][236] The types of food consumed, and how they are prepared, have varied widely by time, location, and culture.[237][238]

In general, humans can survive for up to eight weeks without food, depending on stored body fat.[239] Survival without water is usually limited to three or four days, with a maximum of one week.[240] In 2020, it was estimated 9 million humans die every year from causes directly or indirectly related to starvation.[241][242] Childhood malnutrition is also common and contributes to the global burden of disease.[243] However, global food distribution is not even, and obesity among some human populations has increased rapidly, leading to health complications and increased mortality in some developed and a few developing countries. Worldwide, over one billion people are obese,[244] while in the United States 35% of people are obese, leading to this being described as an "obesity epidemic."[245] Obesity is caused by consuming more calories than are expended, so excessive weight gain is usually caused by an energy-dense diet.[244]

Biological variation

There is biological variation in the human species – with traits such as blood type, genetic diseases, cranial features, facial features, organ systems, eye color, hair color and texture, height and build, and skin color varying across the globe. The typical height of an adult human is between 1.4 and 1.9 m (4 ft 7 in and 6 ft 3 in), although this varies significantly depending on sex, ethnic origin, and family bloodlines.[246][247] Body size is partly determined by genes and is also significantly influenced by environmental factors such as diet, exercise, and sleep patterns.[248]

There is evidence that populations have adapted genetically to various external factors. The genes that allow adult humans to digest lactose are present in high frequencies in populations that have long histories of cattle domestication and are more dependent on cow milk.[249] Sickle cell anemia, which may provide increased resistance to malaria, is frequent in populations where malaria is endemic.[250][251] Populations that have for a very long time inhabited specific climates tend to have developed specific phenotypes that are beneficial for those environments – short stature and stocky build in cold regions, tall and lanky in hot regions, and with high lung capacities or other adaptations at high altitudes.[252] Some populations have evolved highly unique adaptations to very specific environmental conditions, such as those advantageous to ocean-dwelling lifestyles and freediving in the Bajau.[253]

Human hair ranges in color from red to blond to brown to black, which is the most frequent.[254] Hair color depends on the amount of melanin, with concentrations fading with increased age, leading to grey or even white hair. Skin color can range from darkest brown to lightest peach, or even nearly white or colorless in cases of albinism.[255] It tends to vary clinally and generally correlates with the level of ultraviolet radiation in a particular geographic area, with darker skin mostly around the equator.[256] Skin darkening may have evolved as protection against ultraviolet solar radiation.[257] Light skin pigmentation protects against depletion of vitamin D, which requires sunlight to make.[258] Human skin also has a capacity to darken (tan) in response to exposure to ultraviolet radiation.[259][260]

There is relatively little variation between human geographical populations, and most of the variation that occurs is at the individual level.[255][261][262] Much of human variation is continuous, often with no clear points of demarcation.[263][264][265][266] Genetic data shows that no matter how population groups are defined, two people from the same population group are almost as different from each other as two people from any two different population groups.[267][268][269] Dark-skinned populations that are found in Africa, Australia, and South Asia are not closely related to each other.[270][271]

Genetic research has demonstrated that human populations native to the African continent are the most genetically diverse[272] and genetic diversity decreases with migratory distance from Africa, possibly the result of bottlenecks during human migration.[273][274] These non-African populations acquired new genetic inputs from local admixture with archaic populations and have much greater variation from Neanderthals and Denisovans than is found in Africa,[191] though Neanderthal admixture into African populations may be underestimated.[275] Furthermore, recent studies have found that populations in sub-Saharan Africa, and particularly West Africa, have ancestral genetic variation which predates modern humans and has been lost in most non-African populations. Some of this ancestry is thought to originate from admixture with an unknown archaic hominin that diverged before the split of Neanderthals and modern humans.[276][277]

Humans are a gonochoric species, meaning they are divided into male and female sexes.[278][279][280] The greatest degree of genetic variation exists between males and females. While the nucleotide genetic variation of individuals of the same sex across global populations is no greater than 0.1%–0.5%, the genetic difference between males and females is between 1% and 2%. Males on average are 15% heavier and 15 cm (6 in) taller than females.[281][282] On average, men have about 40–50% more upper-body strength and 20–30% more lower-body strength than women at the same weight, due to higher amounts of muscle and larger muscle fibers.[283] Women generally have a higher body fat percentage than men.[284] Women have lighter skin than men of the same population; this has been explained by a higher need for vitamin D in females during pregnancy and lactation.[285] As there are chromosomal differences between females and males, some X and Y chromosome-related conditions and disorders only affect either men or women.[286] After allowing for body weight and volume, the male voice is usually an octave deeper than the female voice.[287] Women have a longer life span in almost every population around the world.[288] There are intersex conditions in the human population, however these are rare.[289][290]

Psychology

The human brain, the focal point of the central nervous system in humans, controls the peripheral nervous system. In addition to controlling "lower", involuntary, or primarily autonomic activities such as respiration and digestion, it is also the locus of "higher" order functioning such as thought, reasoning, and abstraction.[291] These cognitive processes constitute the mind, and, along with their behavioral consequences, are studied in the field of psychology.

Humans have a larger and more developed prefrontal cortex than other primates, the region of the brain associated with higher cognition.[292][293] This has led humans to proclaim themselves to be more intelligent than any other known species.[294] Objectively defining intelligence is difficult, with other animals adapting senses and excelling in areas that humans are unable to.[295]

There are some traits that, although not strictly unique, do set humans apart from other animals.[296] Humans may be the only animals who have episodic memory and who can engage in "mental time travel".[297] Even compared with other social animals, humans have an unusually high degree of flexibility in their facial expressions.[298] Humans are the only animals known to cry emotional tears.[299] Humans are one of the few animals able to self-recognize in mirror tests[300] and there is also debate over to what extent humans are the only animals with a theory of mind.[301][302]

Sleep and dreaming

Humans are generally diurnal. The average sleep requirement is between seven and nine hours per day for an adult and nine to ten hours per day for a child; elderly people usually sleep for six to seven hours. Having less sleep than this is common among humans, even though sleep deprivation can have negative health effects. A sustained restriction of adult sleep to four hours per day has been shown to correlate with changes in physiology and mental state, including reduced memory, fatigue, aggression, and bodily discomfort.[303]

During sleep humans dream, where they experience sensory images and sounds. Dreaming is stimulated by the pons and mostly occurs during the REM phase of sleep.[304] The length of a dream can vary, from a few seconds up to 30 minutes.[305] Humans have three to five dreams per night, and some may have up to seven.[306] Dreamers are more likely to remember the dream if awakened during the REM phase. The events in dreams are generally outside the control of the dreamer, with the exception of lucid dreaming, where the dreamer is self-aware.[307] Dreams can at times make a creative thought occur or give a sense of inspiration.[308]

Consciousness and thought

Human consciousness, at its simplest, is sentience or awareness of internal or external existence.[309] Despite centuries of analyses, definitions, explanations and debates by philosophers and scientists, consciousness remains puzzling and controversial,[310] being "at once the most familiar and most mysterious aspect of our lives".[311] The only widely agreed notion about the topic is the intuition that it exists.[312] Opinions differ about what exactly needs to be studied and explained as consciousness. Some philosophers divide consciousness into phenomenal consciousness, which is sensory experience itself, and access consciousness, which can be used for reasoning or directly controlling actions.[313] It is sometimes synonymous with 'the mind', and at other times, an aspect of it. Historically it is associated with introspection, private thought, imagination and volition.[314] It now often includes some kind of experience, cognition, feeling or perception. It may be 'awareness', or 'awareness of awareness', or self-awareness.[315] There might be different levels or orders of consciousness,[316] or different kinds of consciousness, or just one kind with different features.[317]

The process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses is known as cognition.[318] The human brain perceives the external world through the senses, and each individual human is influenced greatly by his or her experiences, leading to subjective views of existence and the passage of time.[319] The nature of thought is central to psychology and related fields. Cognitive psychology studies cognition, the mental processes underlying behavior.[320] Largely focusing on the development of the human mind through the life span, developmental psychology seeks to understand how people come to perceive, understand, and act within the world and how these processes change as they age.[321][322] This may focus on intellectual, cognitive, neural, social, or moral development. Psychologists have developed intelligence tests and the concept of intelligence quotient in order to assess the relative intelligence of human beings and study its distribution among population.[323]

Motivation and emotion

Human motivation is not yet wholly understood. From a psychological perspective, Maslow's hierarchy of needs is a well-established theory that can be defined as the process of satisfying certain needs in ascending order of complexity.[324] From a more general, philosophical perspective, human motivation can be defined as a commitment to, or withdrawal from, various goals requiring the application of human ability. Furthermore, incentive and preference are both factors, as are any perceived links between incentives and preferences. Volition may also be involved, in which case willpower is also a factor. Ideally, both motivation and volition ensure the selection, striving for, and realization of goals in an optimal manner, a function beginning in childhood and continuing throughout a lifetime in a process known as socialization.[325]

Emotions are biological states associated with the nervous system[326][327] brought on by neurophysiological changes variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure.[328][329] They are often intertwined with mood, temperament, personality, disposition, creativity,[330] and motivation. Emotion has a significant influence on human behavior and their ability to learn.[331] Acting on extreme or uncontrolled emotions can lead to social disorder and crime,[332] with studies showing criminals may have a lower emotional intelligence than normal.[333]

Emotional experiences perceived as pleasant, such as joy, interest or contentment, contrast with those perceived as unpleasant, like anxiety, sadness, anger, and despair.[334] Happiness, or the state of being happy, is a human emotional condition. The definition of happiness is a common philosophical topic. Some define it as experiencing the feeling of positive emotional affects, while avoiding the negative ones.[335][336] Others see it as an appraisal of life satisfaction or quality of life.[337] Recent research suggests that being happy might involve experiencing some negative emotions when humans feel they are warranted.[338]

Sexuality and love

For humans, sexuality involves biological, erotic, physical, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors.[339][340] Because it is a broad term, which has varied with historical contexts over time, it lacks a precise definition.[340] The biological and physical aspects of sexuality largely concern the human reproductive functions, including the human sexual response cycle.[339][340] Sexuality also affects and is affected by cultural, political, legal, philosophical, moral, ethical, and religious aspects of life.[339][340] Sexual desire, or libido, is a basic mental state present at the beginning of sexual behavior. Studies show that men desire sex more than women and masturbate more often.[341]

Humans can fall anywhere along a continuous scale of sexual orientation,[342] although most humans are heterosexual.[343][344] While homosexual behavior occurs in some other animals, only humans and domestic sheep have so far been found to exhibit exclusive preference for same-sex relationships.[343] Most evidence supports nonsocial, biological causes of sexual orientation,[343] as cultures that are very tolerant of homosexuality do not have significantly higher rates of it.[344][345] Research in neuroscience and genetics suggests that other aspects of human sexuality are biologically influenced as well.[346]

Love most commonly refers to a feeling of strong attraction or emotional attachment. It can be impersonal (the love of an object, ideal, or strong political or spiritual connection) or interpersonal (love between humans).[347] When in love dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin and other chemicals stimulate the brain's pleasure center, leading to side effects such as increased heart rate, loss of appetite and sleep, and an intense feeling of excitement.[348]

Culture

| Most widely spoken languages[349][350] | English, Mandarin Chinese, Hindi, Spanish, Standard Arabic, Bengali, French, Russian, Portuguese, Urdu |

|---|---|

| Most practiced religions[350][351] | Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, folk religions, Sikhism, Judaism, unaffiliated |

Humanity's unprecedented set of intellectual skills were a key factor in the species' eventual technological advancement and concomitant domination of the biosphere.[352] Disregarding extinct hominids, humans are the only animals known to teach generalizable information,[353] innately deploy recursive embedding to generate and communicate complex concepts,[354] engage in the "folk physics" required for competent tool design,[355][356] or cook food in the wild.[357] Teaching and learning preserves the cultural and ethnographic identity of human societies.[358] Other traits and behaviors that are mostly unique to humans include starting fires,[359] phoneme structuring[360] and vocal learning.[361]

Language

While many species communicate, language is unique to humans, a defining feature of humanity, and a cultural universal.[362] Unlike the limited systems of other animals, human language is open – an infinite number of meanings can be produced by combining a limited number of symbols.[363][364] Human language also has the capacity of displacement, using words to represent things and happenings that are not presently or locally occurring but reside in the shared imagination of interlocutors.[157]

Language differs from other forms of communication in that it is modality independent; the same meanings can be conveyed through different media, audibly in speech, visually by sign language or writing, and through tactile media such as braille.[365] Language is central to the communication between humans, and to the sense of identity that unites nations, cultures and ethnic groups.[366] There are approximately six thousand different languages currently in use, including sign languages, and many thousands more that are extinct.[367]

The arts

Human arts can take many forms including visual, literary, and performing. Visual art can range from paintings and sculptures to film, fashion design, and architecture.[368] Literary arts can include prose, poetry, and dramas. The performing arts generally involve theatre, music, and dance.[369][370] Humans often combine the different forms (for example, music videos).[371] Other entities that have been described as having artistic qualities include food preparation, video games, and medicine.[372][373][374] As well as providing entertainment and transferring knowledge, the arts are also used for political purposes.[375]

Art is a defining characteristic of humans and there is evidence for a relationship between creativity and language.[376] The earliest evidence of art was shell engravings made by Homo erectus 300,000 years before modern humans evolved.[377] Art attributed to H. sapiens existed at least 75,000 years ago, with jewellery and drawings found in caves in South Africa.[378][379] There are various hypotheses as to why humans have adapted to the arts. These include allowing them to better problem solve issues, providing a means to control or influence other humans, encouraging cooperation and contribution within a society or increasing the chance of attracting a potential mate.[380] The use of imagination developed through art, combined with logic may have given early humans an evolutionary advantage.[376]

Evidence of humans engaging in musical activities predates cave art and so far music has been practiced by virtually all known human cultures.[381] There exists a wide variety of music genres and ethnic musics; with humans' musical abilities being related to other abilities, including complex social human behaviours.[381] It has been shown that human brains respond to music by becoming synchronized with the rhythm and beat, a process called entrainment.[382] Dance is also a form of human expression found in all cultures[383] and may have evolved as a way to help early humans communicate.[384] Listening to music and observing dance stimulates the orbitofrontal cortex and other pleasure sensing areas of the brain.[385]

Unlike speaking, reading and writing does not come naturally to humans and must be taught.[386] Still, literature has been present before the invention of words and language, with 30,000-year-old paintings on walls inside some caves portraying a series of dramatic scenes.[387] One of the oldest surviving works of literature is the Epic of Gilgamesh, first engraved on ancient Babylonian tablets about 4,000 years ago.[388] Beyond simply passing down knowledge, the use and sharing of imaginative fiction through stories might have helped develop humans' capabilities for communication and increased the likelihood of securing a mate.[389] Storytelling may also be used as a way to provide the audience with moral lessons and encourage cooperation.[387]

Tools and technologies

Stone tools were used by proto-humans at least 2.5 million years ago.[391] The use and manufacture of tools has been put forward as the ability that defines humans more than anything else[392] and has historically been seen as an important evolutionary step.[393] The technology became much more sophisticated about 1.8 million years ago,[392] with the controlled use of fire beginning around 1 million years ago.[394][395] The wheel and wheeled vehicles appeared simultaneously in several regions some time in the fourth millennium BC.[70] The development of more complex tools and technologies allowed land to be cultivated and animals to be domesticated, thus proving essential in the development of agriculture – what is known as the Neolithic Revolution.[396]

China developed paper, the printing press, gunpowder, the compass and other important inventions.[397] The continued improvements in smelting allowed forging of copper, bronze, iron and eventually steel, which is used in railways, skyscrapers and many other products.[398] This coincided with the Industrial Revolution, where the invention of automated machines brought major changes to humans' lifestyles.[399] Modern technology is observed as progressing exponentially,[400] with major innovations in the 20th century including: electricity, penicillin, semiconductors, internal combustion engines, the Internet, nitrogen fixing fertilizers, airplanes, computers, automobiles, contraceptive pills, nuclear fission, the green revolution, radio, scientific plant breeding, rockets, air conditioning, television and the assembly line.[401]

Religion and spirituality

Definitions of religion vary;[402] according to one definition, a religion is a belief system concerning the supernatural, sacred or divine, and practices, values, institutions and rituals associated with such belief. Some religions also have a moral code. The evolution and the history of the first religions have become areas of active scientific investigation.[403][404][405] Credible evidence of religious behaviour dates to the Middle Paleolithic era (45–200 thousand years ago).[406] It may have evolved to play a role in helping enforce and encourage cooperation between humans.[407]

Religion manifests in diverse forms.[402] Religion can include a belief in life after death,[408] the origin of life, the nature of the universe (religious cosmology) and its ultimate fate (eschatology), and moral or ethical teachings.[409] Views on transcendence and immanence vary substantially; traditions variously espouse monism, deism, pantheism, and theism (including polytheism and monotheism).[410]

Although measuring religiosity is difficult,[411] a majority of humans profess some variety of religious or spiritual belief.[412] In 2015 the plurality were Christian followed by Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists.[413] As of 2015, about 16%, or slightly under 1.2 billion humans, were irreligious, including those with no religious beliefs or no identity with any religion.[414]

Science and philosophy

An aspect unique to humans is their ability to transmit knowledge from one generation to the next and to continually build on this information to develop tools, scientific laws and other advances to pass on further.[415] This accumulated knowledge can be tested to answer questions or make predictions about how the universe functions and has been very successful in advancing human ascendancy.[416]

Aristotle has been described as the first scientist,[417] and preceded the rise of scientific thought through the Hellenistic period.[418] Other early advances in science came from the Han dynasty in China and during the Islamic Golden Age.[419][96] The scientific revolution, near the end of the Renaissance, led to the emergence of modern science.[420]

A chain of events and influences led to the development of the scientific method, a process of observation and experimentation that is used to differentiate science from pseudoscience.[421] An understanding of mathematics is unique to humans, although other species of animals have some numerical cognition.[422] All of science can be divided into three major branches, the formal sciences (e.g., logic and mathematics), which are concerned with formal systems, the applied sciences (e.g., engineering, medicine), which are focused on practical applications, and the empirical sciences, which are based on empirical observation and are in turn divided into natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, biology) and social sciences (e.g., psychology, economics, sociology).[423]

Philosophy is a field of study where humans seek to understand fundamental truths about themselves and the world in which they live.[424] Philosophical inquiry has been a major feature in the development of humans' intellectual history.[425] It has been described as the "no man's land" between definitive scientific knowledge and dogmatic religious teachings.[426] Major fields of philosophy include metaphysics, epistemology, logic, and axiology (which includes ethics and aesthetics).[427]

Society

Society is the system of organizations and institutions arising from interaction between humans. Humans are highly social and tend to live in large complex social groups. They can be divided into different groups according to their income, wealth, power, reputation and other factors. The structure of social stratification and the degree of social mobility differs, especially between modern and traditional societies.[428] Human groups range from the size of families to nations. The first form of human social organization is thought to have resembled hunter-gatherer band societies.[429]

Gender

Human societies typically exhibit gender identities and gender roles that distinguish between masculine and feminine characteristics and prescribe the range of acceptable behaviours and attitudes for their members based on their sex.[430][431] The most common categorisation is a gender binary of men and women.[432] Some societies recognize a third gender,[433] or less commonly a fourth or fifth.[434][435] In some other societies, non-binary is used as an umbrella term for a range of gender identities that are not solely male or female.[436]

Gender roles are often associated with a division of norms, practices, dress, behavior, rights, duties, privileges, status, and power, with men enjoying more rights and privileges than women in most societies, both today and in the past.[437] As a social construct,[438] gender roles are not fixed and vary historically within a society. Challenges to predominant gender norms have recurred in many societies.[439][440] Little is known about gender roles in the earliest human societies. Early modern humans probably had a range of gender roles similar to that of modern cultures from at least the Upper Paleolithic, while the Neanderthals were less sexually dimorphic and there is evidence that the behavioural difference between males and females was minimal.[441]

Kinship

All human societies organize, recognize and classify types of social relationships based on relations between parents, children and other descendants (consanguinity), and relations through marriage (affinity). There is also a third type applied to godparents or adoptive children (fictive). These culturally defined relationships are referred to as kinship. In many societies, it is one of the most important social organizing principles and plays a role in transmitting status and inheritance.[442] All societies have rules of incest taboo, according to which marriage between certain kinds of kin relations is prohibited, and some also have rules of preferential marriage with certain kin relations.[443]

Pair bonding is a ubiquitous feature of human sexual relationships, whether it is manifested as serial monogamy, polygyny, or polyandry.[444] Genetic evidence indicates that humans were predominantly polygynous for most of their existence as a species, but that this began to shift during the Neolithic, when monogamy started becoming widespread concomitantly with the transition from nomadic to sedentary societies.[445] Anatomical evidence in the form of second-to-fourth digit ratios, a biomarker for prenatal androgen effects, likewise indicates modern humans were polygynous during the Pleistocene.[446]

Ethnicity

Human ethnic groups are a social category that identifies together as a group based on shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. These can be a common set of traditions, ancestry, language, history, society, culture, nation, religion, or social treatment within their residing area.[447][448] Ethnicity is separate from the concept of race, which is based on physical characteristics, although both are socially constructed.[449] Assigning ethnicity to a certain population is complicated, as even within common ethnic designations there can be a diverse range of subgroups, and the makeup of these ethnic groups can change over time at both the collective and individual level.[183] Also, there is no generally accepted definition of what constitutes an ethnic group.[450] Ethnic groupings can play a powerful role in the social identity and solidarity of ethnopolitical units. This has been closely tied to the rise of the nation state as the predominant form of political organization in the 19th and 20th centuries.[451][452][453]

Government and politics

As farming populations gathered in larger and denser communities, interactions between these different groups increased. This led to the development of governance within and between the communities.[454] Humans have evolved the ability to change affiliation with various social groups relatively easily, including previously strong political alliances, if doing so is seen as providing personal advantages.[455] This cognitive flexibility allows individual humans to change their political ideologies, with those with higher flexibility less likely to support authoritarian and nationalistic stances.[456]

Governments create laws and policies that affect the citizens that they govern. There have been many forms of government throughout human history, each having various means of obtaining power and the ability to exert diverse controls on the population.[457] Approximately 47% of humans live in some form of a democracy, 17% in a hybrid regime, and 37% in an authoritarian regime.[458] Many countries belong to international organizations and alliances; the largest of these is the United Nations, with 193 member states.[459]

Trade and economics

Trade, the voluntary exchange of goods and services, is seen as a characteristic that differentiates humans from other animals and has been cited as a practice that gave Homo sapiens a major advantage over other hominids.[460] Evidence suggests early H. sapiens made use of long-distance trade routes to exchange goods and ideas, leading to cultural explosions and providing additional food sources when hunting was sparse, while such trade networks did not exist for the now extinct Neanderthals.[461][462] Early trade likely involved materials for creating tools like obsidian.[463] The first truly international trade routes were around the spice trade through the Roman and medieval periods.[464]

Early human economies were more likely to be based around gift giving instead of a bartering system.[465] Early money consisted of commodities; the oldest being in the form of cattle and the most widely used being cowrie shells.[466] Money has since evolved into governmental issued coins, paper and electronic money.[466] Human study of economics is a social science that looks at how societies distribute scarce resources among different people.[467] There are massive inequalities in the division of wealth among humans; the eight richest humans are worth the same monetary value as the poorest half of all the human population.[468]

Conflict

Humans commit violence on other humans at a rate comparable to other primates, but have an increased preference for killing adults, infanticide being more common among other primates.[469] Phylogenetic analysis predicts that 2% of early H. sapiens would be murdered, rising to 12% during the medieval period, before dropping to below 2% in modern times.[470] There is great variation in violence between human populations, with rates of homicide about 0.01% in societies that have legal systems and strong cultural attitudes against violence.[471]

The willingness of humans to kill other members of their species en masse through organized conflict (i.e., war) has long been the subject of debate. One school of thought holds that war evolved as a means to eliminate competitors, and has always been an innate human characteristic. Another suggests that war is a relatively recent phenomenon and has appeared due to changing social conditions.[472] While not settled, current evidence indicates warlike predispositions only became common about 10,000 years ago, and in many places much more recently than that.[472] War has had a high cost on human life; it is estimated that during the 20th century, between 167 million and 188 million people died as a result of war.[473] War casualty data is less reliable for pre-medieval times, especially global figures. But compared with any period over the past 600 years, the last ~80 years (post 1946), has seen a very significant drop in global military and civilian death rates due to armed conflict.[474]

See also

Notes

- ^ The world population and population density statistics are updated automatically from a template that uses the CIA World Factbook and United Nations World Population Prospects.[129][130]

- ^ Cities with over 10 million inhabitants as of 2018.[131]

- ^ Traditionally this has been explained by conflicting evolutionary pressures involved in bipedalism and encephalization (called the obstetrical dilemma), but recent research suggest it might be more complicated than that.[205][206]

References

- ^ Roopnarine PD (March 2014). "Humans are apex predators". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (9): E796. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111E.796R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1323645111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3948303. PMID 24497513.

- ^ Stokstad E (5 May 2019). "Landmark analysis documents the alarming global decline of nature". Science. AAAS. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Pimm S, Raven P, Peterson A, Sekercioglu CH, Ehrlich PR (July 2006). "Human impacts on the rates of recent, present, and future bird extinctions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (29): 10941–10946. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10310941P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604181103. PMC 1544153. PMID 16829570.

- ^ Spamer EE (29 January 1999). "Know Thyself: Responsible Science and the Lectotype of Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences. 149 (1): 109–114. JSTOR 4065043.

- ^ Porkorny (1959). IEW. s.v. "g'hðem" pp. 414–116.

- ^ "Homo". Dictionary.com. Random House. 23 September 2008. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008.

- ^ a b Barras, Colin (11 January 2016). "We don't know which species should be classed as 'human'". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Spamer EE (1999). "Know Thyself: Responsible Science and the Lectotype of Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 149: 109–114. ISSN 0097-3157. JSTOR 4065043.

- ^ OED. s.v. "human".

- ^ "Man". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

Definition 2: a man belonging to a particular category (as by birth, residence, membership, or occupation) – usually used in combination

- ^ "Thesaurus results for human". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "Misconceptions about evolution – Understanding Evolution". University of California, Berkeley. 19 September 2021. Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "Concept of Personhood". University of Missouri School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Tuttle RH (4 October 2018). "Hominoidea: conceptual history". In Trevathan W, Cartmill M, Dufour D, Larsen C (eds.). International Encyclopedia of Biological Anthropology. Hoboken, New Jersey, United States: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9781118584538.ieba0246. ISBN 978-1-118-58442-2. S2CID 240125199. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Goodman M, Tagle DA, Fitch DH, Bailey W, Czelusniak J, Koop BF, et al. (March 1990). "Primate evolution at the DNA level and a classification of hominoids". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 30 (3): 260–266. Bibcode:1990JMolE..30..260G. doi:10.1007/BF02099995. PMID 2109087. S2CID 2112935.

- ^ Ruvolo M (March 1997). "Molecular phylogeny of the hominoids: inferences from multiple independent DNA sequence data sets". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 14 (3): 248–265. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025761. PMID 9066793.

- ^ MacAndrew A. "Human Chromosome 2 is a fusion of two ancestral chromosomes". Evolution pages. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2006.

- ^ McNulty, Kieran P. (2016). "Hominin Taxonomy and Phylogeny: What's In A Name?". Nature Education Knowledge. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Strait DS (September 2010). "The Evolutionary History of the Australopiths". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 3 (3): 341–352. doi:10.1007/s12052-010-0249-6. ISSN 1936-6434. S2CID 31979188.

- ^ Dunsworth HM (September 2010). "Origin of the Genus Homo". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 3 (3): 353–366. doi:10.1007/s12052-010-0247-8. ISSN 1936-6434. S2CID 43116946.

- ^ Kimbel WH, Villmoare B (July 2016). "From Australopithecus to Homo: the transition that wasn't". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150248. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0248. PMC 4920303. PMID 27298460. S2CID 20267830.

- ^ a b Villmoare B, Kimbel WH, Seyoum C, Campisano CJ, DiMaggio EN, Rowan J, et al. (March 2015). "Paleoanthropology. Early Homo at 2.8 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1352–1355. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1352V. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1343. PMID 25739410.

- ^ Püschel, Hans P.; Bertrand, Ornella C.; O’Reilly, Joseph E.; Bobe, René; Püschel, Thomas A. (June 2021). "Divergence-time estimates for hominins provide insight into encephalization and body mass trends in human evolution". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 5 (6): 808–819. Bibcode:2021NatEE...5..808P. doi:10.1038/s41559-021-01431-1. hdl:20.500.11820/35151870-c7b5-477e-aca8-2c75c8382002. PMID 33795855. S2CID 232764044.

- ^ Clark, G.; Henneberg, M. (2017). "Ardipithecus ramidus and the evolution of language and singing: An early origin for hominin vocal capability". Homo. 68 (2): 101–121. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2017.03.001. PMID 28363458.

- ^ H Kimbel, William; Suwa, Gen; Asfaw, Berhane; Rak, Yoel; D White, Tim (6 January 2014). "Ardipithecus ramidus and the evolution of the human cranial base". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (3): 948–953. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111..948K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322639111. PMC 3903226. PMID 24395771.

- ^ Boisserie, J.-R. (2010). "Ardipithecus ramidus and the birth of humanity". Annales d'Éthiopie. 25: 271–281. doi:10.3406/ethio.2010.1420. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2025.

- ^ D. Lemonick, Michael; Dorfman, Andrea (1 October 2009). "Ardi Is a New Piece for the Evolution Puzzle". Times. Retrieved 18 February 2025.

Lovejoy thinks Ar. ramidus had a social system found in no other primates except humans.

- ^ McPherron, S.P.; Alemseged, Z.; Marean, C.W.; Wynn, J.G.; Reed, D.; Geraads, D.; et al. (August 2010). "Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia". Nature. 466 (7308): 857–860. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..857M. doi:10.1038/nature09248. PMID 20703305. S2CID 4356816.

- ^ Wood, Bernard (28 June 2011). "Did early Homo migrate "out of" or "in to" Africa?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (26): 10375–10376. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10810375W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1107724108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3127876. PMID 21677194.

- ^ Zhu Z, Dennell R, Huang W, Wu Y, Qiu S, Yang S, et al. (July 2018). "Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago". Nature. 559 (7715): 608–612. Bibcode:2018Natur.559..608Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0299-4. PMID 29995848. S2CID 49670311.

- ^ Hublin JJ, Ben-Ncer A, Bailey SE, Freidline SE, Neubauer S, Skinner MM, et al. (June 2017). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens" (PDF). Nature. 546 (7657): 289–292. Bibcode:2017Natur.546..289H. doi:10.1038/nature22336. PMID 28593953. S2CID 256771372. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Out of Africa Revisited". Science (This Week in Science). 308 (5724): 921. 13 May 2005. doi:10.1126/science.308.5724.921g. ISSN 0036-8075. S2CID 220100436.

- ^ Stringer C (June 2003). "Human evolution: Out of Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6941): 692–693, 695. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..692S. doi:10.1038/423692a. PMID 12802315. S2CID 26693109.

- ^ Johanson D (May 2001). "Origins of Modern Humans: Multiregional or Out of Africa?". actionbioscience. Washington, DC: American Institute of Biological Sciences. Archived from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ^ Marean, Curtis; et al. (2007). "Early human use of marine resources and pigment in South Africa during the Middle Pleistocene" (PDF). Nature. 449 (7164): 905–908. Bibcode:2007Natur.449..905M. doi:10.1038/nature06204. PMID 17943129. S2CID 4387442. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Brooks AS, Yellen JE, Potts R, Behrensmeyer AK, Deino AL, Leslie DE, Ambrose SH, Ferguson JR, d'Errico F, Zipkin AM, Whittaker S, Post J, Veatch EG, Foecke K, Clark JB (2018). "Long-distance stone transport and pigment use in the earliest Middle Stone Age". Science. 360 (6384): 90–94. Bibcode:2018Sci...360...90B. doi:10.1126/science.aao2646. PMID 29545508.

- ^ Wilkins, Jayne; Schoville, Benjamin J. (June 2024). "Did climate change make Homo sapiens innovative, and if yes, how? Debated perspectives on the African Pleistocene record". Quaternary Science Advances. 14: 100179. Bibcode:2024QSAdv..1400179W. doi:10.1016/j.qsa.2024.100179.

- ^ Posth C, Renaud G, Mittnik A, Drucker DG, Rougier H, Cupillard C, et al. (March 2016). "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe" (PDF). Current Biology. 26 (6): 827–833. Bibcode:2016CBio...26..827P. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.037. hdl:2440/114930. PMID 26853362. S2CID 140098861. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 March 2025. Retrieved 11 March 2025.

- ^ Karmin M, Saag L, Vicente M, Wilson Sayres MA, Järve M, Talas UG, et al. (April 2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–466. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088.

- ^ Armitage SJ, Jasim SA, Marks AE, Parker AG, Usik VI, Uerpmann HP (January 2011). "The southern route "out of Africa": evidence for an early expansion of modern humans into Arabia". Science. 331 (6016): 453–456. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..453A. doi:10.1126/science.1199113. PMID 21273486. S2CID 20296624. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ Rincon P (27 January 2011). "Humans 'left Africa much earlier'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 August 2012.

- ^ Clarkson C, Jacobs Z, Marwick B, Fullagar R, Wallis L, Smith M, et al. (July 2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago". Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C. doi:10.1038/nature22968. hdl:2440/107043. PMID 28726833. S2CID 205257212. Archived from the original on 15 August 2024. Retrieved 11 March 2025.

- ^ Lowe DJ (2008). "Polynesian settlement of New Zealand and the impacts of volcanism on early Maori society: an update" (PDF). University of Waikato. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ Appenzeller T (May 2012). "Human migrations: Eastern odyssey". Nature. 485 (7396): 24–26. Bibcode:2012Natur.485...24A. doi:10.1038/485024a. PMID 22552074.

- ^ a b Reich D, Green RE, Kircher M, Krause J, Patterson N, Durand EY, et al. (December 2010). "Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia". Nature. 468 (7327): 1053–1060. Bibcode:2010Natur.468.1053R. doi:10.1038/nature09710. hdl:10230/25596. PMC 4306417. PMID 21179161.

- ^ Hammer MF (May 2013). "Human Hybrids" (PDF). Scientific American. 308 (5): 66–71. Bibcode:2013SciAm.308e..66H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0513-66. PMID 23627222. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2018.

- ^ Yong E (July 2011). "Mosaic humans, the hybrid species". New Scientist. 211 (2823): 34–38. Bibcode:2011NewSc.211...34Y. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(11)61839-3.

- ^ Ackermann RR, Mackay A, Arnold ML (October 2015). "The Hybrid Origin of "Modern" Humans". Evolutionary Biology. 43 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s11692-015-9348-1. S2CID 14329491.

- ^ Noonan JP (May 2010). "Neanderthal genomics and the evolution of modern humans". Genome Research. 20 (5): 547–553. doi:10.1101/gr.076000.108. PMC 2860157. PMID 20439435.

- ^ Abi-Rached L, Jobin MJ, Kulkarni S, McWhinnie A, Dalva K, Gragert L, et al. (October 2011). "The shaping of modern human immune systems by multiregional admixture with archaic humans". Science. 334 (6052): 89–94. Bibcode:2011Sci...334...89A. doi:10.1126/science.1209202. PMC 3677943. PMID 21868630.

- ^ Sandel, Aaron A. (30 July 2013). "Brief communication: Hair density and body mass in mammals and the evolution of human hairlessness". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 152 (1): 145–150. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22333. hdl:2027.42/99654. PMID 23900811. Archived from the original on 22 July 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ Boyd R, Silk JB (2003). How Humans Evolved. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-97854-4.

- ^ Little, Michael A.; Blumler, Mark A. (2015). "Hunter-Gatherers". In Muehlenbein, Michael P. (ed.). Basics in Human Evolution. Boston: Academic. pp. 323–335. ISBN 978-0-12-802652-6. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Scarre, Chris (2018). "The world transformed: from foragers and farmers to states and empires". In Scarre, Chris (ed.). The Human Past: World Prehistory and the Development of Human Societies (4th ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 174–197. ISBN 978-0-500-29335-5.

- ^ Colledge S, Conolly J, Dobney K, Manning K, Shennan S (2013). Origins and Spread of Domestic Animals in Southwest Asia and Europe. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast. pp. 13–17. ISBN 978-1-61132-324-5.

- ^ Scanes CG (January 2018). "The Neolithic Revolution, Animal Domestication, and Early Forms of Animal Agriculture". In Scanes CG, Toukhsati SR (eds.). Animals and Human Society. Elsevier. pp. 103–131. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-805247-1.00006-X. ISBN 978-0-12-805247-1.