Human rights in Western Sahara

| Part of a series on the |

| Western Sahara conflict |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Regions |

| Politics |

| Clashes |

| Issues |

| Peace process |

The Government of Morocco sees Western Sahara as its Southern Provinces. The Moroccan government considers the Polisario Front as a separatist movement given the alleged Moroccan origins of some of its leaders.

The Polisario Front argues that according to international organizations, like the United Nations or the African Union, the territory of Western Sahara has the right of self-determination, and that according to those organizations Morocco illegally occupies the parts of Western Sahara under its control. Polisario regards this as a consequence of the vision of a Great Morocco, fuelled in the past by the Istiqlal and Hassan II, and considers itself a national liberation movement aiming at leading the disputed territory to independence under the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic.

The European Union, the African Union and the United Nations do not recognize the sovereignty of Morocco over Western Sahara.

Human rights

[edit]This section may contain an excessive number of citations. (May 2022) |

The Western Sahara conflict has resulted in severe human rights abuses, most notably the aerial bombardments with Napalm and White phosphorus of the Sahrawi refugee camps,[1] the consequent exodus of tens of thousands of Sahrawi civilians from the country, and the forced expropriation and expulsion of tens of thousands of Moroccan civilians by the Algerian government from Algeria in reaction to the Green March[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][excessive citations] as well as violations of human rights and serious breaches of the Geneva convention by the Polisario Front, the Moroccan government and the Algerian government.[10]

Both Morocco and the Polisario accuse each other of violating the human rights of the populations under their control, in the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara and the Tindouf refugee camps in Algeria, respectively. Morocco and organisations such as France Libertés consider Algeria to be directly responsible for any crimes committed on its territory, and accuse the country of having been directly involved in such violations.[11][10]

Morocco has been repeatedly condemned and criticized for its actions in Western Sahara by several international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as:

- Amnesty International[12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][excessive citations]

- Human Rights Watch[23][24]

- World Organization Against Torture[25][26][27]

- Freedom House[28]

- Reporters Without Borders[29][30][31][32][33][34][35]

- International Committee of the Red Cross

- UN High Commissioner for Human Rights[36][37][38]

- Derechos Human Rights[39]

- Defend International[40][41]

- Front Line Defenders[42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][excessive citations]

- International Federation of Human Rights[52][53][54][55][56][57]

- Society for Threatened Peoples[58][59][60][61][62]

- Norwegian Refugee Council[63]

- Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights[64][65][66][67][68][69][70]

- Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies[71][72][73]

- Arabic Network for Human Rights Information[74][75][76][77]

- Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network[78]

Polisario has received criticism from the French organization France Libertes on its treatment of Moroccan prisoners-of-war,[10] and on its general behaviour in the Tindouf refugee camps in reports by the European Strategic Intelligence and Security Center. A number of former members of Polisario who have joined Morocco accuse the organisation of abuse of human rights and sequestration of the population in Tindouf.[79][80][81][82]

During the war (1975–91), both sides accused each other of targeting civilians. Neither claim has met with support abroad. The USA, EU, AU and UN refused to include the Polisario Front on their lists of terrorist organizations. Polisario Front leaders maintain that they are ideologically opposed to terrorism, as they had condemned terrorist attacks[83][84][85] and signed the "Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism", in the framework of the African Union.[86][87]

Human rights are repressed in the Moroccan-controlled territories of Western Sahara, according to Amnesty International in 2003 and Human Rights Watch in 2004.[88] While the situation has improved since the early 1990s, the political liberalization in Morocco has not had the same effect on Western Sahara according to Amnesty International in 2004.,[89] when it comes to having a pro-independence position. There are allegations of police abuse and torture by Polisario-organisations.,[90] and suspected dissidents are harassed. The United States State Department reported in 2000 that there were arbitrary arrests of Sahrawis and no organized labor.[91] Prisoners of conscience were kept in squalid conditions according to Polisario-groups.[92] Some Sahrawis also complain of systematic discrimination in favor of Moroccan settlers.

The Moroccan response to the demonstrations of 2005 was aggressive, and provoked international reactions.[93] In a criticised[94] mass trial in December 2005, 14 leading Sahrawi activists were sentenced to prison sentences; many more had previously been detained. Most of these prisoners were later released by royal decree in the spring of 2006,[95][96] but some have since again been rearrested.

According to the US State Department's 2006 report on Morocco "The law generally provides for freedom of speech and of the press. The government generally respected these rights in practice, as long as Islam, the monarchy, and territorial integrity (the inclusion of the Western Sahara) were not criticized. Throughout the year several publications tested the boundaries of press freedom."[97]

The US State Department's 2005 report on Morocco's attitude towards human rights noted that "[i]n 2004 various international human rights groups estimated that 700 persons were imprisoned for advocating Western Saharan independence."[98] Foreign journalists and visiting missions have been prevented from visiting the territory and in some instances deported from it.[99][89] In 2004, Moroccan newsman Ali Lmrabet was sentenced to heavy fines and ten-year ban on practicing journalism, for referring in an article to the Sahrawis in Tindouf, Algeria, as being "refugees" rather than "sequestered" or "kidnapped", as is the official Moroccan position.[98] Sahrawi human rights organizations have been refused permission to operate in Morocco: the Sahrawi branch of the Moroccan Forum for Truth and Justice (FVJ) was dissolved in 2003, and its members arrested.[100][101] They were later released in the royal amnesties of 2006, or before that, even if some have since been rearrested again. Presently, several organisations, such as the ASVDH, operate illegally, with activists occasionally subject to arrests and harassment, whereas others, such as the Polisario close AFAPREDESA, are mainly active in exile.

Sahrawi activists have tried to compensate for this through extensive use of the Internet, reporting from illegal demonstrations, and documenting police abuse and torture through online pictures and video. Morocco has responded by blockading Internet access to these sites in Morocco and in Western Sahara, prompting accusations of Internet censorship.[102][103] On 20 December 2005 Reporters Without Borders reported that Morocco has added Anonymizer to its Internet blacklist, days after the association recommended the service to Moroccans and Sahrawis wishing to access the banned Sahrawi sites. "These websites, promoting independence for Western Sahara, have been censored since the beginning of December" it reports.[104]

Human rights in Morocco-controlled Western Sahara

[edit]The most severe accusations of human rights abuses by the Kingdom of Morocco are the bombings with napalm and White phosphorus of the improvised refugee camps in Western Sahara in early 1976, killing hundreds of civilians, as well as the fate of hundreds of "disappeared" Sahrawi civilians sequestered by Moroccan military or police forces, most of them during the Western Sahara War. Other accusations are the torture, repression and imprisonment of Sahrawis who oppose peacefully the Moroccan occupation, the expulsion from the territory of foreign journalist, teachers and NGO members, the discrimination of the Sahrawis on the labor and the spoliation of the natural resources of the territory.[citation needed]

On the 15th Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council, former prisoner, human rights defender and second vice-president of CODESA (Collective of Sahrawi Human Rights Defenders) El Mami Amar Salem denounced that more than 30,000 Sahrawi citizens had been tortured by Moroccan forces since 1975.[105]

The "disappeared"

[edit]In 2010 around 520 Sahrawi civilians remained "disappeared" by Moroccan forces, according to human rights groups; some estimate that the total number of "disappeared" could be as high as 1,500.[106] In the past, Morocco denied that any such political prisoners existed, but in 1991 released nearly 200 "disappeared" prisoners, many of whom had been held in secret detention centers since the mid-1970s. Since then, there have been no further releases of "disappeared" prisoners. Amnesty International stated in a 1999 report that:[citation needed]

"The men, women and even children who "disappeared" in Western Sahara came from all walks of life. Many were detained because of their alleged pro-independence activities, support for the Polisario Front, and opposition to Morocco's control of the Western Sahara. Others, including elderly people and children, "disappeared" because of their family links with known or suspected opponents to Moroccan government policy in Western Sahara."

— Amnesty International report 1999

.

In May 2005, the remains of 43 Sahrawi "disappeared" were exhumed from secret prisons on the south of Morocco (Kalaat Maguna, Tagunit). They were detained in Western Sahara (Laayoune, Smara) & southern Morocco (Tan-Tan, Assa) in the 1970s and 1980s.[107]

In 2008, the head of CORCAS and former leader of the Sahrawi National Union Party, Khelli Henna Ould Rachid, declared:

- "Some Moroccan army officers have made what might be called war crimes against prisoners outside the scope of the war ... Many civilians were launched into space from helicopters or buried alive simply for being Sahrawis".[108][full citation needed]

The same year (4 January) construction workers uncovered a mass grave with approximately 15 skeletons in Smara, in former military barracks built during the 1970s, the period during which multiple Sahrawis disappeared or were murdered by Moroccan authorities.[109]

Resulting from the "Reconciliation tribunals" in Morocco in 2005, some graves of political dissidents of Hassan II regime (Sahrawis & Moroccans) were uncovered, although the responsible persons of those crimes have never been judged or their identities revealed. Also, the testimonies of witnesses have not been published yet.[110]

In March 2010, a new grave was found by Bou Craa workers on a phosphate mine with 7 corpses, supposedly Sahrawi nomads killed by Moroccan forces during the mid-1970s.[111]

Freedom House

[edit]

In late 2005, the international democracy watchdog Freedom House listed the abuses of human rights by Morocco. Those relating to political processes were: controlling elections and not allowing Sahrawis to form political associations (such as labor organizations) or non-governmental organizations. The paper included reports of repressive measures against demonstrators.[112][113]

Amnesty International

[edit]

After repeatedly calling attention to alleged human rights violations in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, Amnesty International (AI) received, in April 2006, two detailed responses from the Moroccan Ministry of Justice. The Ministry declared that human rights defenders were not stopped and were not taken into custody because of their opinions, but because of their implication in acts liable to infractions of the law. It stressed that they were guaranteed their full civil liberties and gave precise details concerning the investigations in progress into the allegations of torture relating to Houssein Lidri and Brahim Noumria. In addition, the letter refuted the specific allegations of harassing and intimidation with regard to other demonstrators in the Sahara.

Amnesty International responded by claiming that the authorities have not answered the principal concern of the organization regarding the equity of the lawsuits of Sahrawi protestors. For instance, no mention was made in connection with the allegations of torture and ill-treatment of detainees, and allegations that defendants were not authorized to quote witnesses for the defence.[114]

In June 2006, Amnesty International released its 2005 report on Morocco and Western Sahara,[115] again citing excessive police force, leading to the death of two demonstrators. In the section: "Protests in Western Sahara" Amnesty reports: "Dozens of people were charged with inciting or participating in violence in the demonstrations. Over 20 were later convicted and some were sentenced to several years in prison. Among those sentenced were seven long-standing human rights defenders who were monitoring and disseminating information on the crackdown by the security forces. Two alleged that they had been tortured during questioning. An eighth human rights defender was detained awaiting trial at the end of the year. All eight were possible prisoners of conscience."

Child recruitment

[edit]War Resisters' International[116] stated in 1998 that Morocco conscripts citizens, including Sahrawis in the Moroccan-controlled parts of Western Sahara, into the army; it was a punishable offence to resist. The WRI also cited sources from 1993 saying that "[r]eports indicate that Moroccan authorities in the south have strongly urged under-eighteens to enlist in the armed forces. Fourteen and fifteen-year-old boys in southern Morocco and in the occupied territory of Western Sahara have been allowed to enlist",[117] further citing a source from 1994 that "there are many human rights abuses against the Sahrawi population.So far there has been no investigation of the conduct of the Moroccan army in this conflict."[117] Conscription for the Moroccan army was abolished in 2006.[citation needed]

Polisario Prisoners of War

[edit]In addition to the civilian "disappeared", the Polisario Front accuses the Moroccan government of refusing to provide information on the Sahrawi prisoners of war, who were captured on the battlefield during the war years (1975–91). Morocco long denied holding any war prisoners, but in 1996 released 66 Polisario Front POWs, who were then evacuated to the refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria under international supervision.[118] Polisario maintains that 151 POWs are still missing after being captured by the Moroccan Army, and requests that the Moroccan government shall release them or clarify their fate.[119] Morocco claims it no longer holds any prisoners of war.

Expulsion of Christian foreign workers

[edit]Morocco has occasionally expelled small numbers of missionary groups,[120] some funded by U.S. evangelical Churches, in Morocco and in the Western Sahara parts that it controls. But in March 2010, aid groups and Western countries diplomats denounced that only in that month 70 Christian foreign aid workers were expelled without any trial. Some of them were from USA, New Zealand, Netherlands and United Kingdom, causing the protest of some ambassadors.[121] While the Moroccan government accused them of trying to convert children to Christianity, and of proselytism, the Christian groups claim that the government was trying to restrict their work at the "Village of Hope" children's home, for abandoned and orphaned children.[122] Another case was the deportation from El Aaiun of the Spanish teacher Sara Domene.[123] She had been working as a Spanish teacher since 2007. The Moroccan governor of the El Aaiun province sent an expulsion note to the Spanish embassy in Rabat, accusing her of "being a serious threat to the public order and her expulsion is imperative to safeguard public order", in other words, an accusation of proselytism. Sara stated that despite being Evangelic, she is a philologist, and that she exclusively taught Spanish language classes, using the money she earned for a centre for handicapped persons. Sara was expelled 48 hours after she was given notice.[124]

Status at 2010

[edit]In October 2006, a secret report by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees leaked to the media by the Norwegian Support Committee for Western Sahara[125] detailing the deteriorating condition of human rights in the occupied territory of Western Sahara. The report details several eyewitness testimonies regarding violence associated with the Independence Intifada, particularly of the Moroccan police against peaceful demonstrators.

In March 2010, the Sahrawi human rights activist Rachid Sghir was beaten by Moroccan policemen after an interview with the BBC.[126]

On 28 August, Moroccan police arrested 11 Spanish activists, who were demonstrating for independence for the disputed territory in El Aaiun. They claimed that the police had beat them, releasing a photo of one of the wounded.[127]

In September 2010, a delegation comprising 70 Sahrawis from the Moroccan-controlled part of Western Sahara participate in the International Symposium "The right of peoples to resist: the case of Sahrawi people" in Algiers.[128] On their return to El Aaiun airport, the group decided flying in three different groups, accompanied with international observers and journalists. The first group entered without difficulties, but some individuals of the second group were beaten by the police. The third group joined the rest in a house in El Aaiun, surrounded by the police, and finally held a sit in protest in the street, with their mouths taped-up.[129][130]

In October, thousands of Sahrawis fled from El Aaiun and other towns to the outskirts of Lemseid oasis (Gdeim Izik), raising up a campament of thousands of "jaimas" (Sahrawi tents) called the "Dignity camp", in the biggest Sahrawi mobilization since the Spanish retreat.[131] They protest for the discrimination of Sahrawis in labor and for the exploitation of the natural resources of Western Sahara by Morocco.[132] The protest, that started with a few jaimas on 9 October, grew up to more than 10,000 persons on 21 October.[133] Other campaments were erected in the outskirts of Bojador, Smara and El Aaiun, but were disbanded by Moroccan police. The "Gdeim Izik" campament was surrounded by troops of the Moroccan Army and policemen, who made a blockage of water, food and medicines to the camp.[134][135] On 24 October, a SUV that was trying to enter the camp was machine-gunned by Moroccan soldiers, killing Elgarhi Nayem, a 14-year-old Sahrawi boy, and wounding the other five passengers.[136] The Moroccan Interior ministry claimed that the SUV was gunned after shots rang out of the vehicle,[137] which was denied by their families. According to Sahrawi sources, Elgarhi was buried in secret by the Moroccan authorities, without autopsy or the consent of his family.[138] By that days, the camp had grow to more than 20,000 inhabitants. The Moroccan Army had encircled the camp with a wall of sand and stones, controlling the only access to the camp.[139] On 31 October, Tiago Viera (president of the World Federation of Democratic Youth) was expelled from El Aaiun airport, first to Casablanca and then returned to Lisbon, for alleged "irregularities" when he was trying to visit the camp.[140] Also that day, eight Spanish activists that also tried to reach Gdeim Izik were retained by Moroccan police on a boat in the port of El Aaiun, when they were confronted by a crowd of Moroccans who make death-threats on them. Police stated that they cannot guarantee their safety, and denied them entering the territory, so they had to return to Las Palmas.[141] On 6 November, three Spanish regional MP's that tried to visit the "Dignity camp" were retained in Casablanca and expelled to Spain the next day without any explanation.[142]

Human rights in Polisario-controlled refugee camps

[edit]

The most severe accusations of human rights abuses by the Polisario Front have been about the detention, killing and the abusive treatment of Moroccan prisoners of war from the late 70s to 2006. Other accusations were that some of the population are kept in the Tindouf refugee camps against their will and did not enjoy freedom of expression. Moroccan newspapers have aired reports of demonstrations being suppressed violently by Polisario forces in the Tindouf camps,[citation needed] but these reports have not been confirmed by international media or human rights organizations.

Several international and Spanish human rights and aid organizations are active in the camps on a permanent basis, and contest the Moroccan allegations; there are several people and organizations that claim the Tindouf camps are a model for running refugee camps democratically.[143] In November 2012, the Representative of the High Commissioner for Refugees in Algeria, Mr. Ralf Gruenert stated: "We have not seen cases of torture in the Saharawi refugee camps".[144][independent source needed]

In April 2010, the Sahrawi government called on the UN to supervise Human rights in the liberated territories (Free Zone) and refugee camps, hoping that Morocco would do the same.[145]

Moroccan Prisoners of War

[edit]Until 1997, Morocco refused to recognize the soldiers captured by the Polisario as POWs, even rejecting their repatriation to their homeland, as it happened with the first groups, liberated unilaterally and unconditionally by the Polisario Front in 1984 and 1989 (by demand of the Italian government of Ciriaco De Mita).[146] On 19 November 1995, the first group of Moroccan soldiers were repatriated to Morocco by mediation of the ICRC, Argentina and the United States.[147] In April 1997, another group of 84 prisoners were released,[148] followed by around 191 more released for the Ramadan festivities on 23 November 1999.[149] Again, Morocco refused to repatriate the soldiers, allegedly because that would mean recognizing that Morocco was at war against the Polisario.[150] Finally on 26 February 2000, a groups of 186 prisoners were repatriated to the Inezgane military base, in Agadir,[151] and another 201 were released and repatriated on 13 December 2000.[152][153]

On 17 January 2002, another 115 POWs were released and repatriated, by request of the Spanish government of Jose Maria Aznar.[154][155] 100 POW's were released on 17 June 2002, by request of the German government of Gerhard Schröder,[156] and were repatriated to Agadir on 7 July 2002.[157] On 10 February 2003, the Polisario released 100 POW's on request from the Spanish government.[158]

In April 2003, the France Libertés foundation led an international mission of inquiry on the conditions of detention of Moroccan prisoners of war long held by the Polisario Front in the Sahrawi refugee camps of Algeria and in the Liberated Territories of Western Sahara. The prisoners (under Red Cross supervision since the 1980s) had been held since the end of hostilities, awaiting the conclusion of a formal peace treaty, but as the cease-fire dragged on over a decade, a number of prisoners had at this time been held between 15 and 20 years, making them the longest-serving POWs in the world.[citation needed] Polisario had begun releasing a few hundred prisoners at 1984, and continued with that liberations during the 1990s and 2000s, in what were referred by countries like USA, Italy, Ireland, Libya, Qatar or Spain as "humanitarian gestures", but its refusal to release the last prisoners remained under criticism from the United Nations.[citation needed] In its report, the French foundation produced detailed accusations of torture, forced labour, arbitrary detentions and summary executions of captured soldiers, and claimed that these and other systematic abuses had evaded the Red Cross. Most of the crimes had allegedly been committed in the 1980s, but some were of a later date. The foundation, which supports Sahrawi self-determination and had worked in the camps before, decided to suspend "its interventions in the Saharawi refugee camps of Tindouf where the forced labour of the POWs has been going on for the past 28 years". The report also accused Algeria of direct involvement in crimes against the POWs, and overall responsibility for their situation.[citation needed] On 14 August 2003, 243 Moroccan POW's were released and repatriated,[159] and another 300 POW's were released on 7 November 2003,[160] by the mediation of Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, through the GIFCA. On 21 June 2004, another group of 100 prisoners of war were released, by a previous request from the Irish government of Bertie Ahern.[161] They were repatriated by the ICRC on 23 June.[162]

The Polisario Front finally released the last 404 POWs on 18 August 2005.[163][164]

Freedom of movement

[edit]In a report published in 2003 Amnesty International concluded that "Freedom of expression, association and movement continued to be restricted in the camps controlled by the Polisario Front, near Tindouf in southwestern Algeria. Those responsible for human rights abuses in the camps in previous years continued to enjoy impunity.".[88] However, in its 2006 update of the annual report, the references to a lack of basic freedoms had been removed (though not the references to human rights abusers).[165]

In 2005 the US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants[166] stated: "The Algerian Government allowed the rebel group, Polisario, to confine nearly a hundred thousand refugees from the disputed Western Sahara to four camps in desolate areas outside Tindouf military zone near the Moroccan border 'for political and military, rather than humanitarian, reasons,' according to one observer. According to Amnesty International, "This group of refugees does not enjoy the right to freedom of movement in Algeria. [...] Those refugees who manage to leave the refugee camps without being authorized to do so are often arrested by the Algerian military and returned to the Polisario authorities, with whom they cooperate closely on matters of security.' Polisario checkpoints surrounded the camps, the Algerian military guarded entry into Tindouf, and police operated checkpoints throughout the country."[167]

The main concern of most human rights organizations seems to be the refugees' problems of basic subsistence, living on a meager diet of foreign aid. Human Rights Watch[168] carried out an extensive research mission in the region in 1995, visiting Morocco, Western Sahara and the Tindouf refugees. Its conclusion on the human rights situation for the Sahrawis in Tindouf was that "we found conditions to be satisfactory, taking into account the difficulties posed by the climate and desolate location".[169]

In 1997 and 1999 respectively, the Canadian Lawyers Association for International Human Rights[170] performed two investigative missions to Western Sahara, the first focused on the Tindouf refugee camps, and the second on conditions in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara. The conclusion of the Tindouf mission states that "the refugee camps in Algeria are highly organized and provide more than just the most basic needs to their inhabitants" and that "It appears that a significant effort is being made to ensure that the population is well-educated and that they participate in the governance of the camps."[171]

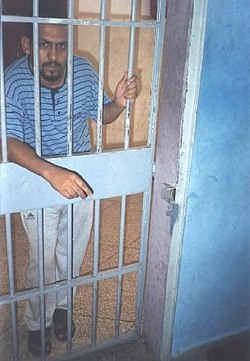

Cuba students programme

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

Polisario is regularly accused by Morocco of deporting Sahrawi children by groups of thousands to Cuba for Communist indoctrination, something which has been supported by alleged former Tindouf refugees now living in Morocco, and former Cuban government officials.[example needed] This would be considered a case of forcible family separation.[by whom?] Morocco has also alleged that the Polisario exports Sahrawi minors to Cuba in order to force them into child prostitution and to train them as child soldiers.[172][173][174][175][176][177][excessive citations] Polisario, which was founded on a left-wing ideology, responds that the children in Cuba, numbering tens or hundreds rather than thousands, are students at Cuban universities, and are there of their own free will under a UNHCR-sponsored student exchange program. It regards the Moroccan accusations as a smear campaign aimed at cutting off access to education for Sahrawi refugees.

While there exists primary education, there are no universities in the refugee camps, and so Sahrawis have to go abroad to study. Similar programmes exist for Sahrawi students in cooperation with universities in Algeria, Spain and Italy, and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic has repeatedly pleaded for more countries to accommodate Sahrawi students. The UNHCR, which oversees the program, has twice investigated the Moroccan claims. In its 2003 report, after having interviewed all 252 Sahrawi students in Cuba, it states that it was the children's own personal will to continue taking advantage of the opportunity to study in Cuba.[citation needed]

In 2005, the UNHCR again examined the issue, after continued Moroccan allegations. The number of students was now down to 143, and the UNHCR program was not expected to be renewed after the graduation of those students. The report[178] states that a number of the Saharan refugee children have availed themselves of scholarships offered within the framework of bilateral relations between the refugee leadership and various countries. The report suggests that this scholarship programme meets the standards of treatment and care required by the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, especially in:

- Protection of the minors from all forms of discrimination while in Cuba, they enjoy equal educational opportunities as well as slightly more advantageous treatment in terms of material and health support provided in Cuban schools.

- Fully respect and guaranty of the rights of the students, in regard to health, nutrition, culture, personal liberty and security.

- Children are not subjected to any form of abuse or exploitation of any type whatsoever. This also covers military recruitment and training and child labour activities that would qualify as exploitative as defined by the CRC.

- All information gathered during the mission affirms the voluntary nature of participation in the programme of the children, the direct role of the parents in determining whether their child would participate, and the opportunity for the children who do not wish to continue the programme, to abandon it and return home.

Child recruitment

[edit]According to a 1998 report by War Resisters' International, "during the guerrilla war" – i.e. between 1975 and 1991 – "Polisario recruitment formed an integral part of the education programme. At the age of 12, children were either integrated into the "National School of 12 October" which prepares the political and military cadres, or they have been sent abroad to Algeria, Cuba and Libya to receive military training as well as regular schooling. At conscription age (17) they returned from abroad to be incorporated into Polisario's armed forces. They received more specialised training in engineering, radio, artillery, mechanics and desert warfare. At nineteen they became combatants."[179]

See also

[edit]- AFAPREDESA

- Ali Salem Tamek

- Aminatou Haidar

- ASVDH

- BIRDHSO

- Brahim Dahane

- History of Western Sahara

- Human rights in Morocco

- Internet censorship and surveillance in Western Sahara

- LGBT rights in the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic

- Mohamed Daddach

- Mohamed Elmoutaoikil

- Tazmamart

References

[edit]- ^ "Article That Provides A Brief History of the Colonisation And Occupation of the Western Sahara By Spain And Then Morocco". New Internationalist. 5 December 1997. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ "Telquel – Maroc/Algérie.Bluff et petites manœuvres". Archived from the original on 15 January 2016.

- ^ جمعية لاسترداد ممتلكات المغاربة المطرودين من الجزائر (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- ^ "La Gazette du Maroc: La "Répudiation massive" de l'Algérie des colonels !". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007.

- ^ "Maroc Hebdo International: Jjgement Dernier". Archived from the original on 9 September 2006.

- ^ "Le Drame des 40.000". Archived from the original on 16 October 2006.

- ^ "Mohamed Elyazghi au Matin du Sahara: Solution politique au Sahara et refondation de nos relations avec Alger". Archived from the original on 10 September 2006.

- ^ "Minorites.org". Archived from the original on 27 April 2006.

- ^ "Revue de Presse des Quotidiens". Archived from the original on 7 January 2009.

- ^ a b c "The Conditions of Detentions of the Moroccan POWs Detained in Tindouf (Algeria)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2016.

- ^ "Arabic News". Archived from the original on 14 October 2013.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: Broken Promises: The Equity and Reconciliation Commission and its Follow-up". Amnesty International. 6 January 2010. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: No more half measures: Addressing enforced disappearances in Morocco and Western Sahara". Amnesty International. 28 August 2009. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Morocco/ Western Sahara: Further Information on UA 16/08 – Fear of unfair imprisonment/ Prisoners of conscience/ Health concern". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Morocco/ Western Sahara: Three years' imprisonment for putting a profile of Prince Moulay Rachid on Facebook". Amnesty International. 25 February 2008. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: New arrests and allegations of torture of Sahrawi human rights defenders". Amnesty International. 31 July 2005. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: Justice must begin with torture inquiries". Amnesty International. 21 June 2005. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: Torture of detainees must end". Amnesty International. 23 June 2004. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: Torture in the "anti-terrorism" campaign – the case of Témara detention centre". Amnesty International. 23 June 2004. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: Briefing to the Committee against torture (November 2003)". Amnesty International. 11 November 2003. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: reports of secret detention and torture on the rise". Amnesty International. 21 February 2003. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Morocco and Western Sahara Human Rights". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: Activists Need Fair Trial". Human Rights Watch. 9 December 2005. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Western Sahara: Keeping It Secret – The United Nations Operation in the Western Sahara". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "OMCT". Archived from the original on 28 August 2005. Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- ^ "OMCT".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "OMCT". Archived from the original on 28 August 2005. Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- ^ "Western Sahara [Morocco] (2006)". Freedomhouse.org. 10 May 2004. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Swedish photographer expelled from Western Sahara a day after his arrest". Reports Without Borders. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Journalist assaulted in the name of Moroccan control of Western Sahara". Reports Without Borders. Archived from the original on 19 September 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Journalists working in Western Sahara face assaults, arrests and harassment". Reports Without Borders. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Western Sahara, government corruption and palace life are all off-limits for the press". Reports Without Borders. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Two Norwegian journalists threatened with expulsion". Reports Without Borders. Archived from the original on 19 September 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Morocco puts US censorship busting site Anonymizer.com on its black list". Reports Without Borders. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Appeal court upholds exorbitant damages award against Journal Hebdomadaire". Reports Without Borders. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Report of the OHCHR to Western Sahara & the refugee camps in Tindouf 2006" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Press briefing notes on Egypt and Western Sahara". Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 19 February 2013. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ "Special Rapporteur Mrs. Sekaggya "very concerned" over Saharawi defenders' conditions". Sahara Press Service. 8 March 2013. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ "Human rights in Morocco & Western Sahara". Derechos.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Wave of arrests in Western Sahara". Defendinternational.com. 31 August 2007. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Morocco: Protect And Preserve Mass Grave Sites". Defendinternational.com. 15 January 2008. Archived from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Western Sahara: Update – Human rights defenders on hunger strike in protest at continued arbitrary detention". Frontlinedefenders.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Western Sahara: Severe beating of human rights defender, Mr Mohammed al-Tahleel by security forces". Frontlinedefenders.org. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Western Sahara: Torture and solitary confinement of human rights defender Mr Yahya Mohamed el Hafed Aaza". Frontlinedefenders.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Western Sahara: Systematic repression of human rights defenders". Frontlinedefenders.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Western Sahara – International Observers harassed as trial of 7 Sahrawi human rights defenders postponed amid violent scenes". Frontlinedefenders.org. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Morocco denies shameful beating of woman human rights defender". Frontlinedefenders.org. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ [Western Sahara: Alleged enforced disappearance of human rights defender, Ms Sukeina Idrissi "Morocco/ Western Sahara – UPDATE – Ennaama Asfari sentenced to 4 months while several trial observers briefly detained"]. Frontlinedefenders.org. 31 August 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Western Sahara: Alleged enforced disappearance of human rights defender, Ms. Sukeina Idrissi". Frontlinedefenders.org. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Western Sahara: Arrest, detention and fear of torture and ill-treatment of human rights defender Mr Hasna Al Wali". Frontlinedefenders.org. 9 January 2012. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Western Sahara: Trial and sentencing of human rights defenders Mr. Atiqu Barrai, Mr. Kamal Al Tarayh, Mr. Abd Al Aziz Barrai, Mr. Al Mahjoub Awlad Al Cheih, Mr. Mohamed Manolo and Mr. Hasna Al Wali". Frontlinedefenders.org. 30 April 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Sahara occidental : Arrestation de M. Duihi Hassan – MAR 001 / 0210 / OBS 024 – FIDH : mouvement mondial des droits de l'Homme". FIDH. 22 November 2011. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Harcèlement à l'encontre de Mme Elghalia Dijim et M. Duihi Hassan – MAR 003 / 1109 / OBS 166 – FIDH : mouvement mondial des droits de l'Homme". FIDH. 22 November 2011. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Détentions arbitraires / Poursuites judiciaires / Mauvais traitements – – FIDH : mouvement mondial des droits de l'Homme". FIDH. 22 November 2011. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Nouvelle condamnation d'un militant sahraoui. – FIDH : mouvement mondial des droits de l'Homme". FIDH. 22 November 2011. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Après l'interdiction de trois hebdomadaires au Maroc, RSF et la FIDH dénoncent une décision inique et inacceptable – FIDH : mouvement mondial des droits de l'Homme". FIDH. 22 November 2011. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "DISPARITIONS FORCEES AU MAROC – FIDH : mouvement mondial des droits de l'Homme". FIDH. 22 November 2011. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Gesellschaft fuer bedrohte Voelker – Society for Threatened Peoples. "EU ignores violations of human rights in Morocco". Gfbv.de. Archived from the original on 28 January 2012.

- ^ Gesellschaft fuer bedrohte Voelker – Society for Threatened Peoples. "Almost 700 arrested in the year 2006". Gfbv.de. Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ Gesellschaft fuer bedrohte Voelker – Society for Threatened Peoples (1 January 2001). "Violation of the right to self-determination of the Sahrauis people in Western Sahara". Gfbv.de. Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ Gesellschaft fuer bedrohte Voelker – Society for Threatened Peoples (17 March 2003). "The right to self-determination of the Saharawi people and the UN peace plan". Gfbv.de. Archived from the original on 11 February 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ Gesellschaft fuer bedrohte Voelker – Society for Threatened Peoples (10 November 2010). "Bleak outlook for Western Sahara; Europe criticized for ambivalent stance". Gfbv.de. Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ OXX Publisher™ (28 March 2008). "Occupied Country, Displaced People". Nrc.no. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "RFK Center observes grave human rights violations in Western Sahara". RFKcenter.org. 3 September 2012. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "RFK Center and Human Rights Watch Urge United Nations to Support Human Rights in Western Sahara". RFKcenter.org. Retrieved 26 September 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Western Sahara: report on human rights violations". RFKcenter.org. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "RFK Center Condemns Brutal Attack of Human Rights Defender's Children in Western Sahara". RFKcenter.org. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Two Years Later, Murder of Sahrawi National Still Uninvestigated". RFKcenter.org. 8 June 2012. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Urgent Action: Call on Secretary of State Clinton to Defend Human Rights in Western Sahara". RFKcenter.org. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "International Coalition calls attention to the human rights situation in Western Sahara". RFKcenter.org. 17 May 2012. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "North African states under scrutiny at Human Rights Council: Even during Universal Periodic Review, rights violations continue". Cihrs.org. 25 September 2012. Archived from the original on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ "International Coalition calls attention to the human rights situation in Western Sahara During the UN Universal Periodic Review of Morocco, International Coalition calls attention to the human rights situation in Western Sahara". Cihrs.org. 17 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ "Human Rights Council must insist Morocco end repression of the Sahrawi People". Cihrs.org. 1 June 2012. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: No Action on Police Beating of Rights Worker". Anhri.net. 15 May 2012. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ "Morocco: Moroccan police suppressed the demonstrations "Laayoune", and assaults two female Sahari activists". Anhri.net. 6 November 2012. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ "Morocco: The police forces repress the Sharai demonstration violently which led to several injuries". Anhri.net. 12 November 2012. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ "Morocco: ANHRI condemns the sentences issued against two of human rights advocates". Anhri.net. 19 November 2012. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ "Morocco: end unjust trials by military courts". Euromedrights.org. 20 February 2013. Archived from the original on 25 February 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ "Guerre de clans et scission inévitable à Tindouf, selon trois ex-responsables du Polisario ayant regagné le Maroc" (in French). Archived from the original on 14 August 2004.

- ^ "Les geôliers de Tindouf mis à nu" (in French). Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- ^ "Quatrieme Commission: Le Maroc Reste Attache Au Plan De Reglement Et A La Tenue D'un Referendum Transparent Au Sahara Occidental" (in French). Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Report: Clan wars and unavoidable scission in Tindouf, defectors". Archived from the original on 14 October 2013.

- ^ "The President of the Republic presents his condolences to the King of Spain and the Head of the Government after terrorist attacks in Madrid". SPS. 11 March 2004. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008.

- ^ "The President of the Republic expresses Saharawi people's condolences to British people". SPS. 7 July 2005. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009.

- ^ "President of Republic consoles his Ugandan counterpart on victims of Kampala bomb attacks". SPS. 14 July 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "OAU Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Protocol to the OAU Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Morocco/Western Sahara". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Amnesty International – Morocco/Western Sahara – Covering events from January – December 2004". Archived from the original on 8 February 2006.

- ^ "Western Sahara – Sahara Occidental -Droits humains". Arso.org. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "US State Department – Western Sahara – Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2000". State.gov. 23 February 2001. Archived from the original on 13 April 2001. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Western Sahara Online – Pictures depicting one of the darkest places of Moroccan occupation, the infamous "Black Prison" in El Aaiun". Wsahara.net. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Amnesty International – Morocco / Western Sahara – Sahrawi human rights defenders under attack". Archived from the original on 16 February 2006.

- ^ "Amnesty International – Public Statement – Morocco/Western Sahara: Human rights defenders jailed after questionable trial". Archived from the original on 4 April 2006.

- ^ "ARSO". Archived from the original on 13 June 2006. Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ^ "Morocco orders captives' release". 22 April 2006.

- ^ "Morocco". State.gov. 6 March 2007. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Morocco". State.gov. 8 March 2006. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "RSF". Archived from the original on 23 June 2006.

- ^ "ARSO". Archived from the original on 26 February 2005. Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ^ "state.gov".

- ^ "RSF". Archived from the original on 18 June 2006.

- ^ "IFEX".

- ^ "Morocco puts US censorship busting site Anonymizer.com on its black list". Reporters Without Borders. 25 November 2011. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Plus de 30 000 Sahraouis torturé depuis l'invasion marocaine" (in French). CODAPSO. 26 September 2010. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ "US Department of State – Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2000 – Morocco". State.gov. 23 February 2001. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Exhumados 50 cadáveres de desaparecidos, entre ellos 43 saharauis". EFE Terra. 9 October 2005. Archived from the original on 30 December 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ Ali Lmrabet. (17 June 2008). "Un responsable marroquí reconoce crímenes de guerra en el Sahara". El Mundo (in Spanish).

- ^ "2008 Human Rights Report: Western Sahara". State.gov. 25 February 2009. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Morocco abuse report criticised". BBC News. 17 December 2005. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "El Polisario anuncia el hallazgo de una fosa común de supuestos represaliados durante la invasión marroquí". Europa Press. 13 March 2010. Archived from the original on 14 August 2010. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "country report Morocco". Archived from the original on 13 May 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- ^ "country report Western Sahara". Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- ^ "Maroc et Sahara Occidental – Procès d'un défenseur sahraoui des droits humains". Amnestyinternational.be. 1 November 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "2005 report on Morocco and Western Sahara". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Morocco: CONCODOC 1998 report". Wri-irg.org. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Morocco". War Resisters' International. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices". 1999.

- ^ "Polisario Front demands from the UN to compel Morocco release political prisoners and account for the 'disappeared'". Sahara Press Service. 21 September 2005. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "Morocco expels five missionaries". BBC. 30 March 2009. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "Morocco steps up expulsions of Christian aid workers". Reuters. 12 March 2010. Archived from the original on 16 March 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "Morocco defends expulsion of Christian workers". BBC. 12 March 2010. Archived from the original on 25 September 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "Morocco deports Spanish teacher from occupied Western Sahara". SPS. 29 June 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Rabat expulsa a una española de El Aaiún por "proselitismo"". El País (in Spanish). 29 June 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Forwarded by Norwegian Support Committee for Western Sahara report by United Nations High Commission for Refugees (8 September 2006). "Report of the OHCHR Mission to Western Sahara and the Refugee Camps in Tindouf 15/23 May and 19 June 2006". United Nations. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bagnall, Sam (20 March 2010). ""Western Sahara activist 'beaten' after talking to BBC". BBC news, March 20, 2010". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Moroccan police arrest 11 Spanish activists". Reuters. 29 August 2010. Archived from the original on 10 November 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ "Launch of international symposium on peoples' right to resist". SPS. 25 September 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Stefan Simanowitz (1 October 2010). "Running the gauntlet: Silent Saharawis protest on streets of Western Sahara". Afrik-News. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ "Recibimiento 30 de septiembre de 2010" (in Spanish). Sahara Thawra. 1 October 2010. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ "Los saharauis realizan su mayor protesta desde hace 35 años". El País (in Spanish). 19 October 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "Western Sahara: Desert protest demanding housing and jobs". ANSAmed. 19 October 2010. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ ""Mass exodus" from Western Sahara cities". Afrol News. 21 October 2010. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ "Exodus in protest of the pillage". Western Sahara Resource Watch. 15 October 2010. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "Los saharauis acampan en masa contra la ocupación marroquí del Sáhara Occidental". El Periódico (in Spanish). 20 October 2010. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ "Teen shot and killed in contested Western Sahara". Metro News (Associated Press). 25 October 2010. Retrieved 2 November 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Boy's murder heightens Western Sahara tension". Euronews. 26 October 2010. Archived from the original on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "20,000 Western Sahara protesters "starving"". Afrol News. 29 October 2010. Archived from the original on 31 October 2010. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "Sáhara.- Unos 20.000 saharauis se han sumado al campamento de protesta de El Aaiún" (in Spanish). Europa Press. 23 October 2010. Archived from the original on 24 October 2010. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ "WFDY President expelled from Morocco!!!". WFDY. 1 November 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ "Spanish Sahara support activists return to base amid threats". ThinkSpain.com. 1 November 2010. Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ "Marruecos guarda silencio sobre la retención de tres españoles". El País (in Spanish). 6 November 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ^ "Sahara Marathon: Host Interview Transcript – James A. Baker III". PBS. 14 September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Algeria 'is not involved' in the conflict of Western Sahara (UN)". Sahara Press Service. 19 November 2012. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ "Polisario calls on UN to supervise human rights in territories under its control". SPS.[dead link]

- ^ "Resolution on the Western Sahara – European parliament, 11 October 1990" (PDF). ARSO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Rapatriement de 185 prisonniers de guerre marocains, libérés en 1989, Communiqué du Ministère de l'Information de la République Arabe Sahraouie Démocratique" (in French). 19 November 1995. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: ICRC visits Moroccan prisoners held by Polisario Front". ICRC. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Le Front Polisario decide de liberer 191 prisonniers de guerre marocains" (in French). SPS. Archived from the original on 15 November 2010.

- ^ "Polisario releases 191 Moroccan prisoners of war". Western Sahara Campaign UK. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: Repatriation of 186 Moroccan prisoners". ICRC. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Press release of the Ministry of Information of the Saharawi Arabic Democratic Republic". ARSO. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: 201 Moroccan prisoners released and repatriated". ICRC. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "El Frente Polisario entrega a Cruz Roja a 115 prisioneros marroquíes". ABC (in Spanish). Madrid. 17 January 2000. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: 115 Moroccan prisoners released and repatriated". Icrc.org. 17 January 2002. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "République Arabe Sahraouie Démocratique, Ministère de l'information – Libération de 100 prisonniers de guerre marocains" (in French). Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Morocco/Western Sahara: 101 Moroccan prisoners released and repatriated". ICRC. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Front Polisario unilaterally releases 100 Moroccan prisoners of war at Spain's request". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Liste de 243 prisonniers de guerre marocains liberes par le Front Polisario, le 13 Aout 2003". Arso.org. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Western Sahara: Polisario releases 300 Moroccan prisoners of war". UN news service. 7 November 2003. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Moroccan prisoners of war". ARSO. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ "100 Moroccan prisoners repatriated". ICRC. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ "Représentation pour l'Europe". ARSO (Polisario Front – Representation to Europe). 17 August 2005. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "404 Moroccan prisoners released". Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "Amnesty International". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "USCRI – Protecting Refugees, Serving Immigrants, and Upholding Freedom Since 1911". Refugees.org. Archived from the original on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants". Archived from the original on 26 January 2011.

- ^ "Defending Human Rights Worldwide". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "Western Sahara – Keeping It Secret – The United Nations Operation in the Western Sahara". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "CLAIHR". Archived from the original on 12 May 2006. Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ^ "CLAIHR". Archived from the original on 4 May 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2006.

- ^ "Children of population sequestered in Tindouf deported by thousands to Cuba, denounces deportation victim". Archived from the original on 5 March 2006.

- ^ "Adults abducted as children by communists to talk".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Today's Editorial". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 23 December 2005. Retrieved 20 May 2006.

- ^ "Saharan Former Refugees Recount Life in Polisario-Controlled Camps Families Separated; Children Forcibly Sent to Cuba; International Aid Stolen".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Former Saharan Refugees Recount Life in Castro's Schools and Polisario-Controlled Camps" (Press release). Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "Deportation of Sahrawi children to Cuba by 'Polisario' denounced". Archived from the original on 1 March 2006.

- ^ "Western Saharan refugee students in Cuba. UNHCR – Information note (September 2005)". Arso.org. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "War Resisters' International". Wri-irg.org. 23 June 1998. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (June 2017) |

- H.R.W. world report 2010: Morocco & Western Sahara

- Amnesty International: Morocco/Western Sahara 2006 Report

- Freedom House: Western Sahara 2010 Report Archived 15 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Human Rights Watch: Morocco – Summary page for Morocco/Western Sahara

- IFEX: Morocco Puts Squeeze on Western Sahara News – IFEX

- UNHCR Western Sahara page

- Human Rights Watch: Keeping It Secret – 1995 investigative mission to Western Sahara and Tindouf.

- R.S.F. – Morocco – Annual report 2006

- R.S.F. – Morocco – 2005 annual report

- R.S.F. – Morocco – Annual Report 2002

- N.R.C. Report on Western Sahara: Occupied Country, Displaced People

- El Observador nº 52: Derechos humanos en el Sáhara Occidental (2008) (in Spanish)

- 2008 International Trade Union visit to the occupied territories in Western Sahara.

- ARSO human rights page ARSO's collection of human rights material

- ARSO political prisoners' page

- CLAIHR visiting mission 1997 – conditions in the Tindouf refugee camps

- CLAIHR visiting mission 1999 – conditions in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara (pdf)

- Asociación de Familiares de Presos y Desaparecidos Saharauis (AFAPREDESA) Archived 10 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine – Exile-based Sahrawi human rights organization

- Asociación Saharaui de las Víctimas de las Violaciones de Derechos Humanos por Marruecos (ASVDH) – Illegalized El Aaiun-based Sahrawi human rights organization

- Colectivo Saharaui de Defensores de los Derechos Humanos (CODESA) (in Arabic) – El Aaiun-based Sahrawi human rights collective

- Comité por la Defensa del Derecho a la Autodeterminación para el Pueblo del Sáhara Occidental (CODAPSO) – Western Sahara based Sahrawi human rights committee, declared illegal by Morocco

- Freedom Sun – Organization for the protection of Sahrawi human rights defenders Archived 29 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine – Western Sahara-based Sahrawi human rights defenders organization

- Association Marocaine de Droits Humaine (AMDH) – Moroccan human rights organization

- International Bureau for the Respect of Human Rights in Western Sahara (BIRDHSO) – Sahrawi human rights organization in exile (Switzerland)

- US State Department – 2009 Country Report for Western Sahara

- US State Department – 2005 Country Report for Western Sahara

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch