Hyopsodus

| Hyopsodus Temporal range: Early Eocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Endocast of the skull of H. lepidus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Family: | †Hyopsodontidae |

| Genus: | †Hyopsodus Leidy, 1870 |

| Type species | |

| †Hypsodus paulus | |

| Species[1] | |

| |

Hyopsodus is a genus of extinct early ungulate mammal of the family Hyopsodontidae, a group associated with or basal to the Perissodactyla. It was a small mammal with skull of about 6 cm in length.[2] Fossils of this genus have been found in the Eocene of North America, especially the Bighorn Basin region of the United States. It has also been found in Eurasia.

Taxonomy

[edit]Eighteen species of Hyopsodus have been described from North America, four from Asia, and two from Europe. The exact number and identity of species has been contested, as is common when taxa are erected based on fragmentary materials. However, there is broad agreement that multiple species in the genus lived in the Wasatchian, Uintan, and Bridgerian North American Land Mammal Ages, and they have been used both to reconstruct paleoenvironments and to study evolutionary change.[3]

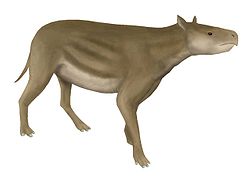

Appearance and habits

[edit]Members of the genus had a long spinal column with short limbs and tail, making them one of the few genera of Paleogene mammal with a common name: "tube-sheep"[4] Reconstructing their appearance in life was originally difficult, as remains are common but often consist only of fragmentary jaws or skulls and teeth. (In H. paulus, this preservation has been observed in predator coprolites, along with lizard scutes.)[5] However, several whole individuals in the genus have been found beautifully preserved in life positions in langerstatten in fossil lakes. They show Hyopsodus individuals had an arched back with a posture similar to a hyrax, rather than a weasel-like tube-shaped body.[6]

Study of the limbs in H. lepidus has shown these animals were not adapted either for life as underground diggers like moles and groundhogs, or for life in the trees. However, they would have moved quickly on the ground, and could have dug for food or shelter as pigs and bandicoots do. An endocast of the brain of H. lepidus has shown it had an excellent sense of smell and an expanded ability to process sounds.[7] Though they did not have a sophisticated echolocation system like bats, they may have had basic terrestrial echolocation to help them avoid or find objects in the dark, like modern shrews and tenrecs.[8] It is likely H. lepidus was a nocturnal ground-dweller in damp closed forests and by the edges of lakes. H. wortmani had strong chest muscles and could have dug burrows or swum.[4] The teeth of all species show they were omnivores; at least one species, H. lovei, had a battery of procumbent incisors worn by chewing, and likely had a specialized diet.[5] In their heyday, Hyopsodus species may have occupied a variety of niches later taken by other flexible forest feeders such as rats, small early perissodactyls, and hypocarnivores like raccoons.

References

[edit]- ^ "Fossilworks: Hyopsodus". Archived from the original on 2022-09-22. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ^ T. S. Kemp (November 4, 2004). The Origin and Evolution of Mammals. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 237. ISBN 9780191545177. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ BIN BAI, YUAN-QING WANG, XIN-YUE ZHANG, and JIN MENG. "A new species of the "condylarth" Hyopsodus from the middle Eocene of the Erlian Basin, Inner Mongolia, China, and its biostratigraphic implications" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 66 (4).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Fossil Mammals - Fossil Butte National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ a b Flynn, John J. (1991). "Hyopsodus (Mammalia) from the Tepee Trail Formation (Eocene), Northwestern Wyoming" (PDF). American Museum Novitates – via Online Library of the American Museum of Natural History, New York.

- ^ Nix, Illustration (June 15, 2020). "Hyopsodus". Nix Illustration. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Orliac, M. J.; Argot, C.; Gilissen, E. (2012). Goswami, Anjali (ed.). "Digital Cranial Endocast of Hyopsodus (Mammalia, "Condylarthra"): A Case of Paleogene Terrestrial Echolocation?". PLOS ONE. 7 (2): e30000. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...730000O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030000. PMC 3277592. PMID 22347998.

- ^ Ravel, Anthony; Orliac, Maeva J. (2015-11-17). "The inner ear morphology of the 'condylarthran' Hyopsodus lepidus". Historical Biology. 27 (8): 957–969. Bibcode:2015HBio...27..957R. doi:10.1080/08912963.2014.915823. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 84391276.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch