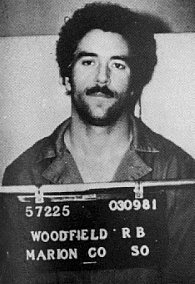

Randall Woodfield

Randall Woodfield | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Randall Brent Woodfield December 26, 1950 |

| Other names |

|

| Conviction(s) | Murder Attempted murder Second-degree robbery Sodomy Sexual assault |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment plus 99 years |

| Details | |

| Victims | 1 convicted, linked to 18, suspected to be involved in 44 |

Span of crimes | October 9, 1980 – February 15, 1981 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Oregon, California |

Date apprehended | March 7, 1981 |

| Imprisoned at | Oregon State Penitentiary |

| American football career | |

| Personal information | |

| Height: | 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) |

| Weight: | 175 lb (79 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school: | Newport (Oregon) |

| College: | Portland State |

| Position: | Wide receiver |

| NFL draft: | 1974 / round: 17 / pick: 428 |

| Career history | |

| * Offseason and/or practice squad member only | |

Randall Brent Woodfield (born December 26, 1950) is an American serial killer, serial rapist, kidnapper, robber, burglar and former football player who was dubbed the I-5 Killer or the I-5 Bandit by the media due to the crimes he committed along the Interstate 5 corridor running through Washington, Oregon and California. Before his capture, Woodfield was suspected of multiple sexual assaults and murders. Though convicted in only one murder, he has been linked to a total of 18 murders and is suspected of having killed up to as many as 44 people.

A native of Oregon, Woodfield was the third child of a prominent Newport family. He began to exhibit abnormal behaviors during his teenage years and was arrested for indecent exposure while still in high school. An athlete for much of his life, Woodfield played as a wide receiver for the Portland State Vikings and was drafted by the National Football League in 1974 to play for the Green Bay Packers, but was cut from the team during training after a series of indecent exposure arrests.[citation needed]

In 1975, Woodfield began a string of robberies and sexual assaults on women in Portland, which he committed at knifepoint. Between 1980 and 1981, he committed multiple murders in cities along the I-5 corridor; his earliest-documented murder was that of Cherie Ayers, a former classmate whom he had known since childhood, in October 1980. After committing numerous violent crimes, Woodfield was arrested in March 1981, and convicted in June of the murder of Shari Hull and attempted murder of her co-worker, Beth Wilmot. He was sentenced to life imprisonment plus 90 years. In a subsequent trial, he was convicted of sodomy and improper use of a weapon in a sexual assault case, receiving 35 additional years to his sentence.

Woodfield has never confessed to any of the crimes of which he has been accused or convicted. Though he has only been convicted of one murder and one attempted murder, he has been linked via DNA and other methods to numerous unsolved homicides in the ensuing decades. Authorities have estimated his total number of killings to be as many as 44. CBS News named him one of the deadliest serial killers in American history.[1] He is currently incarcerated at the Oregon State Penitentiary.

Early life

[edit]Childhood

[edit]Randall Woodfield was born on December 26, 1950,[2] in Salem, Oregon, the third child of an upper-middle-class family.[3][4] His mother was a homemaker, and his father was an executive at Pacific Northwest Bell.[5] He has two older sisters,[3] one of whom went on to become a doctor and the other an attorney.[6] The Woodfield family was "well-known and respected" in their community.[5]

Woodfield was raised in Otter Rock, Oregon, a small seaside town approximately 8 miles (13 km) north of Newport.[5] Popular among his peers, he was a football star at Newport High School.[5] Though his childhood was by all accounts stable, Woodfield began to exhibit sexually dysfunctional behaviors during junior high school, particularly exposing himself in public.[7] While in high school, Woodfield exposed himself to a group of teenage girls on Yaquina Bay Bridge and was arrested.[5] His football coaches helped conceal the incident to prevent him from being ousted from the team,[8] though his parents forced him to attend therapy after the incident.[9]

College years and football career

[edit]After graduating from high school, Woodfield's criminal record was expunged and he attended Treasure Valley Community College in Ontario, Oregon, later transferring to Portland State University in Portland in 1970, where he played for the Portland State Vikings as a wide receiver.[5][10] At Portland State, he was active in Campus Crusade for Christ, an evangelical Christian student group, and lived in an apartment located on the South Park Blocks.[5]

Gary Hamblet, Woodfield's football coach, recalled: "When he was with me, he was the nicest, most gentlemanly kid I ever knew. He was quiet and polite, hard-working and real coachable."[5] Other teammates and peers of Woodfield recalled him as "soft-spoken" and "kind of a loner" who "didn't have a lot of friends," but noted his athleticism.[5]

Despite his thriving in college, Woodfield was arrested on several occasions for petty crimes: first in 1970 for vandalizing the apartment of his ex-girlfriend, and later in 1972 for public indecency[11] in Vancouver, Washington.[6] In 1973 he was arrested again for public indecency in Multnomah County, Oregon.[6]

Woodfield chose to drop out of college three semesters shy of graduating with his B.S. in physical education, and was selected as a wide receiver in the 1974 NFL draft by the Green Bay Packers in the 17th round (428th pick).[11][9] Woodfield tried to establish himself with the Packers during Coach and General Manager Dan Devine's last season, but could not shake his problems with a trip across the country. He signed a contract in February 1974 but was cut during training camp, failing to make the team's final roster.[12][13]

After being cut by the Packers, Woodfield played the 1974 season with the semi-pro Manitowoc Chiefs and worked for Oshkosh Truck.[12]

First crime spree

[edit]Woodfield left Wisconsin in late 1974 and returned to Portland, feeling disgraced by his failure to maintain his football career.[14] In early 1975,[11] several Portland women were accosted by a knife-wielding man, forced to perform oral sex and then robbed of their handbags.[5] Law enforcement responded to the string of crimes by having female police officers act as decoys.[14]

On March 3, 1975, Woodfield was arrested after being caught with marked money from one of the undercover officers. Upon interrogation he confessed to the crimes, blaming poor sexual impulse control, which he claimed was a result of his use of steroids.[14] In April 1975, Woodfield pled guilty to reduced charges of second-degree robbery. He was sentenced to ten years in prison, but was freed on parole in July 1979 after having served four years.[14]

Murders and subsequent crimes

[edit]First murders

[edit]On October 9, 1980, Cherie Lynn Ayers, an X-ray technician and former classmate of Woodfield, was raped and murdered in her apartment at SW Ninth Place in downtown Portland.[6] Her body was discovered on October 11 by her fiancé. She had been bludgeoned and stabbed repeatedly in the neck.[9] Ayers, a University of Oregon graduate, had known Woodfield since second grade, having attended the same schools in Newport.[15]

During Woodfield's prior four-year imprisonment, he and Ayers had corresponded via letters. Suspecting Woodfield's involvement in Cherie Lynn's murder, Ayers' family provided his name to law enforcement. He was questioned but refused to sit for a polygraph test.[15] Homicide detectives found his answers generally "evasive and deceptive" but, because his blood type did not match semen found in the victim's body, no charges were filed.[15]

One month later, on the morning of November 27 (Thanksgiving Day), Woodfield arrived at the north Portland home of Darcey Renee Fix, 22, planning to assault her.[9] Woodfield had known Fix during college as an ex-girlfriend of one his close friends. Douglas Keith Altig, 24, was at Fix's home when Woodfield arrived. Both Fix and Altig were subsequently bound and shot to death execution-style in the home, and Fix's .32 caliber revolver was missing from the scene. Due to his acquaintance with Fix, Woodfield was questioned about the murders, but law enforcement found no concrete evidence pointing to his involvement.[9]

I-5 Bandit robberies

[edit]

After committing the murders of Fix and Altig, Woodfield began a series of robberies throughout the Pacific Northwest: On December 9, 1980, Woodfield, wearing a fake beard, held up a Vancouver, Washington, gas station at gunpoint.[9] In Eugene, Oregon, four nights later, on December 13, he raided an ice cream parlor. On December 14, he robbed a drive-in restaurant in Albany, Oregon.[9] During one of the robberies, Woodfield wore what appeared to be a Band-Aid or athletic tape across the bridge of his nose, similar to nasal strips worn by football players. On December 21, Woodfield (again wearing a false beard) accosted a waitress in Seattle, trapping her in a restaurant bathroom and forcing her at gunpoint to masturbate him.[9]

By January 1981, law enforcement had dubbed the robber the "I-5 Bandit", given his apparent preference for committing crimes along the Interstate 5 corridor. On January 8, he held up the same Vancouver gas station he had robbed in December, this time forcing a female attendant to expose her breasts after he emptied the cash register. Three days later, on January 11, he robbed a market in Eugene. The next day, January 12, he shot and wounded a female grocery clerk at a store in Sutherlin, Oregon.[citation needed]

On January 14, a man matching the description of the I-5 Bandit and wearing a false beard invaded a home occupied by two sisters, aged eight and ten. He ordered the girls to undress and sexually assaulted them, forcing the older girl to perform fellatio. Four days later, in Salem, a man matching the same description entered an office building and sexually abused two women, Shari Hull and Beth Wilmot, after which he killed Hull and wounded Wilmot, leaving her for dead. On January 26 and 29, he traveled to southern Oregon and committed robberies in Eugene, Medford and Grants Pass. In the latter location, two females, a clerk and customer, were assaulted by the robber.[citation needed]

Later murders

[edit]On February 3, 1981, the bodies of Donna Eckard, 37, and her 14-year-old daughter, Janell Charlotte Jarvis, were found together in a bed in their home in Mountain Gate, California, north of Redding. Each had been shot several times in the head. Forensic tests showed that the girl had also been sexually assaulted. The same day in Redding, a female store clerk was kidnapped and raped in a holdup. An identical crime was reported in Yreka, California on February 4, with the same man robbing an Ashland, Oregon motel that night.

Five days later in Corvallis, a man matching the I-5 Bandit's description held up a fabric store, molested the clerk and her customer before he left. On February 12, 1981, robberies committed by a man matching the I-5 Bandit's description occurred in Vancouver, Olympia, and Bellevue, Washington. The Olympia and Bellevue incidents included three sexual assaults.[citation needed]

Upon an impending visit to Portland, Woodfield planned a Valentine's Day party at the city's downtown Marriott Hotel, inviting friends and acquaintances from college.[6] After no guests came, Woodfield drove to the Beaverton home of 18-year-old Julie Reitz, who he had met while working as a bouncer at The Faucet, a bar in Portland. He arrived at her home around 2:00 a.m. on February 15. Around 4:00 a.m. he raped and then shot Reitz in the head, killing her.[6] Police investigating the scene determined that Reitz had had a glass of wine with her attacker and had also begun to prepare coffee; a package of instant coffee was discovered on the kitchen counter, and water in a kettle had been left to completely boil away.[6]

Arrest and trials

[edit]By February 28, the investigation was now focused on Woodfield, but by then the I-5 Bandit had struck three more times — in Eugene on February 18 and 21, and with another sexual assault in Corvallis on February 25. Detectives in Marion County assembled a call log showing Woodfield had placed calls via calling cards at payphones near the murder sites around the times they were committed.[9]

On March 5, 1981, Woodfield was brought into the Salem Police Department for an interrogation after Lisa Garcia positively identified him in a photo lineup.[9] His apartment in Springfield, Oregon, was subsequently searched two days later by warrant; inside, law enforcement discovered a spent .32 shell casing inside a racquetball bag, as well as a roll of tape that matched the tape found on the victims. On March 7, Woodfield was taken into custody after being positively identified by several Oregon robbery victims.[9] On March 16, indictments for murder, rape, sodomy, attempted kidnapping, armed robbery, and illegal possession of firearms were initiated from various jurisdictions in Washington and Oregon.[9]

In the summer of 1981, Woodfield was tried in Salem for the murder of Hull, as well as charges of sodomy and attempted murder (of Wilmot).[16] Wilmot testified against him in the trial, and was key in the prosecution's conviction.[6] Chris Van Dyke, son of actor Dick Van Dyke, was the Marion County District Attorney at the time and prosecuted the case.[14] Van Dyke would later characterize Woodfield as "the coldest, most detached defendant I've ever seen."[6] On June 26, 1981, after three-and-a-half hours of deliberation, Woodfield was convicted on all counts and sentenced to life in prison plus 90 years.[9]

In October 1981, a second trial was held in Benton County, Oregon, in which Woodfield received sodomy and weapons charges tied to one of the attacks in a restaurant bathroom.[9] Prior to this trial, his counsel attempted to move the trial from the Willamette Valley; he felt that, owing to the publicity the case received, Woodfield would not get a fair trial there.[17] The judge in the case denied counsel's request, along with a request to hypnotize a prosecution witness in an effort to determine if that witness had been influenced by the media coverage.[17] Woodfield was convicted by the jury, and had an additional 35 years added to his already-instated sentence.[9]

Despite the apparent links with countless other crimes and homicides, Woodfield would not be prosecuted for the majority of the crimes he was believed to have committed. Unable to afford multiple trials, the State of Oregon was satisfied with Woodfield's existing life sentence.[16]

Post-conviction

[edit]Woodfield is serving his sentences at the Oregon State Penitentiary in Salem.[18] In October 1983, he was injured by a fellow inmate during a prison disturbance.[18] In April 1987, he filed a $12 million libel suit against Ann Rule,[19] the author who had written The I-5 Killer, an account of Woodfield's life and crime spree, in 1984. The Federal Court in Oregon dismissed the lawsuit in January 1988, citing that the statute of limitations on such a lawsuit had expired.[19]

By 1990, after the discovery of more victims, Woodfield was suspected in as many as 44 homicides.[20] In 2001 and 2006, DNA testing linked Woodfield to two additional murders in Oregon that occurred from 1980 and 1981.[21]

During his time in the penitentiary, Woodfield has married three times and divorced twice. Some letters he wrote from prison were sold online as a collection titled The Serial Killer Letters and published by The Charles Press.[12] In one of these letters, he wrote to journalist Jennifer Furio:

You only care to know "why murderers strike out in anger or rage"? How should I know? What a question Jenny. Care to write more personally? Share a photo? Talk once by phone? Your choice.

Ciao

Randall Woodfield[8]

Modus operandi and victim profile

[edit]"He killed and then five weeks later killed again. Then it was three weeks, then two weeks. I believe that it would have soon been every few days. He was like the boogeyman."

The majority of Woodfield's victims were thin white women in their twenties, many of middle-class backgrounds.[9] A great many of his victims—particularly in instances of robbery and sexual assault—were young employees of restaurants and convenience stores located along Interstate 5, which Woodfield traversed in his 1974 Champagne Edition gold Volkswagen Beetle.[22] In some instances, Woodfield's attacks were undertaken entirely at random, while in others, the murders were incited by rejected sexual advances.[9] His level of acquaintance with his victims varied; some he knew personally, while others were complete strangers.[6]

During his robberies, assaults, and killings, Woodfield typically concealed his identity by wearing a hoodie, a fake beard,[23] and most curiously, a strip of athletic tape across his nose.[9] Police believe Woodfield may have done so to obscure his features and prevent victims from identifying him in a police lineup.[6] His victims were typically killed via gunshot, and his crimes were sexually-motivated.[24]

Jim Lawrence, a detective for Portland's cold case unit, noted Woodfield's lack of remorse or responsibility in his crimes, saying: "If you’re talking about somebody moving toward some form of rehabilitation, they had to at some point acknowledge they are responsible for their own behaviors. That is not Randy Woodfield."[9] Lawrence also noted Woodfield's egotism during his early interrogations: "When he was interviewed, he'd tell detectives that he'd never rape a girl. He said he didn't have to. They wanted him."[6] Ann Rule, who documented Woodfield's crimes in The I-5 Killer, suggested that rejection and feelings of inadequacy were factors that drove him to violence, particularly against women.[6] She also characterized Woodfield as a "smooth ladies' man" whose good looks and disposition aided his ability to trap victims.[25]

Unlike many serial killers, whose killing patterns are characterized by intervals or "cooling off periods," Woodfield's murders and other crimes escalated rapidly, increasing in successive frequency.[6]

Victims

[edit]Woodfield never confessed to any of the murders of which he has been convicted, accused or to which he has been linked.[9] Though convicted only in the murder of Shari Hull, Woodfield has been linked to numerous other murders via DNA and other methods; criminologists and detectives have provided estimated total numbers of killings ranging from 25[6] to as many as 44 unsolved homicides.[1][9] Woodfield is also estimated to have committed at least 60 unsolved rapes.[4] The following is a list of Woodfield's confirmed victims:

1980

[edit]- October 9

- Cherie Lynn Ayers (29): A former classmate of Woodfield's; was found in her Portland home on October 11; was bludgeoned and stabbed multiple times in the neck.[9]

- November 27

- Darcey Renee Fix (22) and Douglas Keith Altig (24): Both found shot to death with a .32 revolver in Fix's North Portland home.[26]

- December 21

- Unnamed woman (25): Assaulted at gunpoint in a Seattle restroom, forced to masturbate Woodfield; survived.[9]

1981

[edit]- January 12

- Susie Benet (20): A market clerk in Sutherlin, Oregon, shot by Woodfield during robbery; survived.[27]

- January 18

- Shari Lynn Hull (20) and Beth Wilmot (20): Employees at a Transamerica office in Keizer, Oregon, accosted by Woodfield during their evening work shift; sexually assaulted both women before shooting them each in the head. Hull died of her injuries; Wilmot survived.[9]

- February 3

- Unnamed woman (18): Kidnapped at gunpoint and raped near Redding, California in the morning hours; survived.[9]

- Donna Lee Eckard (37) and daughter Janell Charlotte Jarvis (14): Both found sexually assaulted and shot to death in their Shasta County home.[26]

- February 4

- Unnamed woman: Kidnapped and raped in Yreka, California; survived.[9]

- February 15

- Julie Ann Reitz (18): Raped and shot to death in her Beaverton, Oregon home around 4:00 a.m.;[6] was an acquaintance of Woodfield's through his job as a bartender.[9]

Other possible victims

[edit]Retracing Woodfield's movements along Interstate 5, law enforcement have identified at least 25 other potential murders,[6] while other estimations suggest up to 44.[9] Notable is Martha Morrison (17), who disappeared in Eugene in September 1974 and was found murdered the following month near Vancouver; her remains were unidentified until 2015. Both Woodfield and Ted Bundy have been considered suspects in her murder.[28] However, after Morrison's remains were identified, law enforcement reached out to the public in an effort to encourage people to come forward with tips.[29] In August 2017, a bloodstain on a pistol owned by a longtime suspect, Warren Forrest, was matched to Morrison through DNA testing.[30]

During the spring of 1980, Marsha Weatter (19) and Kathy Allen (18) vanished while hitch-hiking from the Spokane, Washington, area to their hometown of Fairbanks, Alaska. Their bodies were found in May 1981, covered by several inches of ash from the May 18, 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. Suspected serial killer Martin Lee Sanders was later connected to their murders,[31] but as of 2018 the case remains unsolved.

In popular culture

[edit]In 2011, Woodfield was the subject of a Lifetime television film Hunt for the I-5 Killer, based on Ann Rule's book. In the film, Woodfield is portrayed by Canadian actor Tygh Runyan.[32]

See also

[edit]- Green Bay Packers draft history

- List of Portland State Vikings in the NFL draft

- List of serial killers in the United States

- List of serial killers by number of victims

References

[edit]- ^ a b "America's Deadliest Serial Killers: Randall Woodfield". CBS News. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ "Search Warrant: Randall Brent Woodfield" (PDF). State of Oregon. (repub. in Sports Illustrated). March 5, 1981. Retrieved February 9, 2018 – via Google Drive.

- ^ a b Lachmann 2001, p. 123.

- ^ a b Bovsun, Mara (March 23, 2014). "Two killers leave a trail of bodies along Interstate 5 in California in the 1980s". New York Daily News. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Eggers, Kerry (January 24, 2017). "'I-5 Killer' played for PSU before taking dark turn". Portland Tribune. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r The Oregonian Staff (May 12, 2012). "Serial killer Randy Woodfield's legacy: pain, preening and pointlessness". The Oregonian. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ^ Lachmann 2001, pp. 123–124.

- ^ a b Furio, Jennifer (1998). The Serial Killer Letters: A Penetrating Look Inside the Minds of Murderers. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Charles Press. ISBN 978-0914783848. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Wertheim, L. John (November 21, 2016). "The I-5 Killer". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ Rule 1984, p. 304.

- ^ a b c Lamovsky, Rosetti & DeMarco 2007, p. 250.

- ^ a b c Walter, Tony (October 10, 2010). "Serial killer Randall Woodfield was with Green Bay Packers in 1974". Green Bay Press-Gazette. Retrieved February 10, 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Holdings, H.W. (March 2010). "Crime: The Case of the I-5 Killer". 20th & 21st Century Crime. U.S. History.

- ^ a b c d e McPadden, Mike (June 26, 2017). "Randall Woodfield: The Green Bay Packer Who Became the I-5 Killer". CrimeFeed. Investigation Discovery. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c Bernstein, Maxine (March 1, 2006). "DNA links 'I-5 killer' to 1980 slaying". The Oregonian. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ a b National News Briefs. United Press International, October 13, 1981, Tuesday, PM cycle.

- ^ a b Judge refuses a change of venue for I-5 bandit suspect. United Press International, September 24, 1981, Thursday, PM cycle.

- ^ a b Domestic News. United Press International, October 3, 1983, Monday, AM cycle.

- ^ a b Tims, Dana. Murderer's libel suit dismissed. The Oregonian, January 18, 1988.

- ^ Burgess, Anthony. Book Review: The revenge of the failures with time to kill; 'The Serial Killers' - Colin Wilson & Donald Seaman: W H Allen, 6.99 pounds. The Independent, December 21, 1990.

- ^ Bernstein, Maxine. DNA links 'I-5 killer' to 1980 slaying. The Oregonian, February 9, 2006.

- ^ Rule 2004, p. 110.

- ^ Seattle Post-Intelligencer Staff (February 19, 2003). "Suspected or convicted serial killers in Washington". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ^ Newton, Michael (2006). The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers. Infobase Publishing. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-816-06987-3.

- ^ Rule 2004, p. 109.

- ^ a b "'I-5 Killer' connected to five more deaths". KATU. May 10, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- ^ Rule 1984, p. 222.

- ^ Gorrow, Chelsea (October 14, 2014). "After 40 years, Oregon cold case gets a little warmer". The Herald. Everett, Washington. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2018 – via The Eugene Register-Guard.

- ^ "Remains of homicide victim found near Vancouver identified after 41 years | The Columbian". July 2, 2017. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Gillespie, Emily (July 13, 2014). "Remains of homicide victim found near Vancouver identified after 41 years". Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "Montana Convict Faces New Charges". The Seattle Times. May 6, 1990. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ^ "Review: Hunt for the I-5 Killer". Radio Times. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

Works cited

[edit]- Lachmann, Frank M. (2001). Transforming Aggression: Psychotherapy with the Difficult-to-Treat Patient. Jason Aronson, Inc. ISBN 978-1-461-63219-1.

- Lamovsky, Jesse; Rosetti, Matthew; DeMarco, Charlie (2007). The Worst of Sports: Chumps, Cheats, and Chokers from the Games We Love. Random House. ISBN 978-0-345-50227-8.

- Rule, Ann (1984). The I-5 Killer. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 0-451-16559-4.

- Rule, Ann (2004). Kiss Me, Kill Me: Ann Rule's Crime Files. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-416-50003-2.

External links

[edit]- Excerpts of letters by Woodfield published in The Serial Killer Letters (1998)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch