Ian Smith

Ian Smith | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

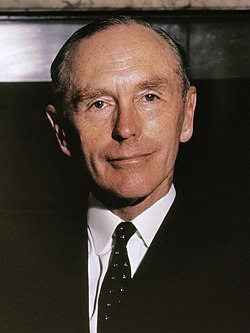

Smith in 1975 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8th Prime Minister of Rhodesia[n 1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 13 April 1964 – 1 June 1979[n 2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarchs (until 1970) | Elizabeth II[n 3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Presidents (from 1970) | Clifford Dupont Henry Everard (acting) John Wrathall Henry Everard (acting) Jack Pithey (acting) Henry Everard (acting) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Clifford Dupont John Wrathall David Smith | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Winston Field | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Abel Muzorewa as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Rhodesia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Ian Douglas Smith 8 April 1919 Selukwe, Rhodesia[n 4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 20 November 2007 (aged 88) Cape Town, South Africa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 3, including Alec | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Rhodes University (BComm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1941–1945 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Flight lieutenant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | Second World War | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Prime Minister of Rhodesia 1964-1979 Government

Battle Career Retirement and final years Family  | ||

Ian Douglas Smith GCLM ID (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1979.[n 2] He was the country's first leader to be born and raised in Rhodesia, and led the predominantly white government that unilaterally declared independence from the United Kingdom in November 1965 in opposition to their demands for the implementation of majority rule as a condition for independence. His 15 years in power were defined by the country's international isolation and involvement in the Rhodesian Bush War, which pitted the Rhodesian Security Forces against the Soviet and Chinese-funded military wings of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU).

Smith was born to British immigrants in the small town of Selukwe in the Southern Rhodesian Midlands, four years before the colony became self-governing in 1923. During the Second World War, he served as a Royal Air Force fighter pilot, where a crash in Egypt resulted in facial and bodily wounds that remained conspicuous for the rest of his life. Following recovery, he served in Europe, where he was shot down and subsequently fought alongside Italian partisans. After the war, he established a farm in his hometown in 1948 and became a Member of Parliament for Selukwe that same year. Originally a member of the Liberal Party, he defected to the United Federal Party in 1953, and served as Chief Whip from 1958 onwards. He left that party in 1961 in protest over the territory's new constitution, and went on to co-found the Rhodesian Front the following year.

Smith became deputy prime minister following the Front's December 1962 election victory, and he stepped up to the premiership after Field resigned in April 1964, two months before the first events that led to the Bush War took place. After repeated talks with British prime minister Harold Wilson broke down, Smith and his Cabinet unilaterally declared independence on 11 November 1965 in an effort to delay majority rule; shortly afterwards, the first phase of the war began in earnest. After further negotiations with the UK failed, Rhodesia cut all remaining British ties and reconstituted itself as a republic in 1970. Smith led the Front to four election victories over the course of his premiership; despite sporadic negotiations with moderate leader Abel Muzorewa over the course of the war, his support came exclusively from the white minority, with the black majority being widely disenfranchised under the country's electoral system.

The country initially endured United Nations sanctions and international isolation with the assistance of South Africa and, until 1974, the Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique. Following 15 years of protracted fighting, with economic sanctions, international pressure and the decline in South African support taking their toll, Smith conceded to the implementation of majority rule and signed the Internal Settlement in 1978 with moderate leaders, excluding ZANU and ZAPU; the country was renamed Zimbabwe Rhodesia the following year. The new order, however, failed to gain international recognition, and the war continued. After being succeeded as prime minister by Muzorawa, Smith took part in the trilateral peace negotiations at Lancaster House, which led to fully free elections and the recognition of an independent Zimbabwe.

Following the election, Smith served as Leader of the Opposition for seven years and marked himself as a strident critic of Robert Mugabe's government. His criticisms persisted after his 1987 retirement: he dedicated much of his 1997 memoir, The Great Betrayal, to condemning Mugabe, UK politicians, and defending his premiership. In 2005, Smith moved to South Africa for medical treatment, where he died two years later at the age of 88. His ashes were subsequently repatriated and scattered at his farm.

As Rhodesia's dominant political figure and public face in its final decades, Smith's reputation and legacy has remained divisive and controversial up to the present day. By his supporters, he has been hailed as "a political visionary ... who understood the uncomfortable truths of Africa",[5] defending his rule as one of stability and a stalwart against communism.[6] His critics, in turn, have condemned him as "an unrepentant racist ... who brought untold suffering to millions of Zimbabweans," as the leader of a white supremacist government responsible for maintaining racial inequality and discriminating against the black majority.[5]

Early life and education

[edit]Family, childhood and adolescence

[edit]

Ian Douglas Smith was born on 8 April 1919 in Selukwe (now Shurugwi), a small mining and farming town about 310 km (190 mi) southwest of the Southern Rhodesian capital Salisbury. He had two elder sisters, Phyllis and Joan.[n 5] His father, John Douglas "Jock" Smith, was born in Northumberland and was raised in Hamilton, South Lanarkshire, Scotland; he was the son of a cattle breeder and butcher. He had emigrated to Rhodesia as a nineteen-year-old in 1898, and became a prominent rancher, butcher, miner and garage owner in Selukwe. Jock and his wife, Agnes (née Hodgson), had met in 1907, when she was sixteen, a year after her family's emigration to Selukwe from Frizington, Cumberland. After Mr Hodgson sent his wife and children back to England in 1908, Jock Smith astonished them in 1911 by arriving unannounced in Cumberland to ask for Agnes's hand; they had not seen each other for three years. They married in Frizington and returned together to Rhodesia, where Jock, an accomplished horseman, won the 1911 Coronation Derby at Salisbury.[8]

The Smith family involved themselves heavily in local affairs. Jock chaired the village management board and commanded the Selukwe Company of the Southern Rhodesia Volunteers; he also became a founding member of the Selukwe Freemasons' Lodge and president of the town's football and rugby clubs. Agnes, who became informally known as "Mrs Jock", established and ran the Selukwe Women's Institute. Both were appointed MBE (at different times) for their services to the community.[9] "My parents strove to instil principles and moral virtues, the sense of right and wrong, of integrity, in their children," Smith wrote in his memoirs. "They set wonderful examples to live up to."[10] He considered his father "a man of extremely strong principles"[11]—"one of the fairest men I have ever met and that is the way he brought me up. He always told me that we're entitled to our half of the country and the blacks are entitled to theirs."[12] Raised on the frontier of the British Empire in the UK's youngest settler colony, Smith and his generation of white Rhodesians grew up with a reputation for being "more British than the British", something in which they took great pride.[13]

Smith showed sporting promise from an early age. After attending the Selukwe primary school, he boarded at Chaplin School in Gwelo, about 30 km (19 mi) away. In his final year at Chaplin, he was head prefect and captain of the school teams in cricket, rugby and tennis, as well as recipient of the Victor Ludorum in athletics and the school's outstanding rifle marksman.[14] "I was an absolute lunatic about sport," he later said; "I concede, looking back, that I should have devoted much more time to my school work and less to sport."[11] All the same, his grades were good enough to win a place at Rhodes University College, in Grahamstown in South Africa, then often attended by Rhodesian students—partly because Rhodesia then had no university of its own, and partly because of the common eponymous association with Cecil Rhodes. Smith enrolled at the start of 1938, reading for a Bachelor of Commerce degree.[14] After injuring his knee playing rugby, he took up rowing and became stroke for the university crew.[15]

Second World War; Royal Air Force pilot

[edit]

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Southern Rhodesia had had self-government for 16 years, having gained responsible government from the UK in 1923. It was unique in the British Empire and Commonwealth in that it held extensive autonomous powers (including defence, but not foreign affairs) while lacking dominion status. As a British colony, Southern Rhodesia entered the conflict automatically when Britain declared war on 3 September 1939, but its government issued a symbolic declaration of war anyway.[16] Smith, who was about halfway through his university course, later described feeling patriotically compelled to put his studies aside to "fight for Britain and all that it represented".[17] Excited by the idea of flying a Spitfire,[17] he wanted to join the air force, but was prevented from immediately doing so by a policy adopted in Rhodesia not to recruit university students until after they graduated.[18] Smith engineered his recruitment into the Royal Air Force (RAF) in spite of this rule during 1940, suppressing mention of his studies,[17] and formally joined in September 1941.[19]

After a year's training at Gwelo under the Empire Air Training Scheme,[20] Smith passed out with the rank of pilot officer in September 1942.[21] He hoped to be stationed in Britain,[22] but was posted to the Middle East instead; there he joined No. 237 (Rhodesia) Squadron RAF, flying Hurricanes.[23] In October 1943, in Egypt, Smith crashed his Hurricane after his throttle malfunctioned during a dawn takeoff.[24] In addition to sustaining serious facial disfigurements, he also broke his jaw, leg and shoulder.[23] Doctors and surgeons in Cairo rebuilt Smith's face through skin grafts and plastic surgery,[25] and he was passed fit to fly again in March 1944.[22] Turning down an offer to return to Rhodesia as an instructor,[25] he rejoined No. 237 Squadron, which had switched to flying Spitfire Mk IXs, in Corsica in May 1944.[26]

During a strafing raid over northern Italy on 22 June 1944,[19] enemy flak hit Smith's craft and he had to bail out behind German lines.[27] A peasant family named Zunino hid him for a brief time;[28] he then joined a group of pro-Allied Italian partisans, with whom he took part in sabotage operations against the German garrison for about three months. When the Germans pulled out of the area in October 1944, Smith left to try to link up with the Allied forces who had just invaded southern France. Accompanied by three other servicemen, each from a different European country, and a local guide, Smith hiked across the Maritime Alps, finishing the journey walking barefoot on the ice and snow. American troops recovered him in November 1944.[29] Smith again turned down the offer of a billet in Rhodesia[30] and returned to active service in April 1945 with No. 130 (Punjab) Squadron, by then based in western Germany. He flew combat missions there, "[having] a little bit of fun shooting up odd things", he recalled, until the war in Europe ended on 8 May 1945 with Germany's surrender. Smith remained with No. 130 Squadron for the rest of his service, flying with the unit to Denmark and Norway, and was discharged at the end of 1945 with the rank of flight lieutenant.[31] He retained reasonable proficiency in Italian for the rest of his life, albeit reportedly with an "atrocious" accent.[32]

Graduation, marriage and entrance to politics

[edit]

With Jock in increasingly poor health after the war, the Smith family briefly considered sending Ian to live in the United States with the help of Jock's brother Elijah, who had become a prosperous New York businessman. Smith showed little interest in leaving Rhodesia, however,[33] and decided that he would finish at university, then come home and buy his own farm. He returned to Rhodes University in early 1946 to find the campus swamped with veterans like himself—400 of them out of barely 1,000 students. Smith became spokesman for the university's ex-servicemen, senior student of his hall and chairman of the students' representative council. He turned down the presidency of the rowing club, saying it would be one administrative commitment too many, but agreed to coach the crew. Training the rowers under strict military-style discipline, he led them to victory at the 1946 South African Inter-Varsity Boat Race at the Vaal Dam south of Johannesburg, upstaging the well-fancied Wits crew, and subsequently received national-standard varsity honours for rowing, the first Rhodes student ever to do so. At the end of the year, having passed the exams to gain his commerce degree ("by some miracle", he recalled), he returned to Southern Rhodesia to study farming at Gwebi Agricultural College, near Salisbury.[34]

Smith attended dedicated courses for ex-servicemen at Gwebi during 1947 and 1948, learning skills such as ploughing, herding and milking; he gained practical experience at Taylor's dairy farm near Selukwe and on a tobacco ranch at Marandellas.[35] In 1947, he met Janet Duvenage (née Watt),[36] a schoolteacher from the Cape in South Africa who had come to Selukwe to stay with family after the death of her husband Piet on the rugby field. What Janet had planned as a short holiday for herself and her two infant children, Jean and Robert, turned into a permanent move when she accepted a job offer from the Selukwe junior school.[37] Smith later wrote that the qualities that had attracted him most to Janet were her intelligence, courage and "oppos[ition] on principle to side-stepping or evading an issue ... her tendency was to opt for a decision requiring courage, as opposed to taking the easy way out".[36] They became engaged in 1948. Meanwhile, Smith negotiated the purchase of a piece of rough land near Selukwe, bounded by the Lundi and Impali Rivers and bisected by a clear stream.[36] He and Janet gave the previously nameless 3,600-acre (15 km2) plot the name that the local Karanga people used to refer to the stream, "Gwenoro",[n 6] and set up a ranch where they ran cattle and grew tobacco and maize.[38]

A general election was called in Southern Rhodesia in July 1948 after the United Party government, headed by the Prime Minister Sir Godfrey Huggins, unexpectedly lost a vote in the Legislative Assembly. In August, about a month before election day, members of the opposition Liberal Party approached Smith and asked him to stand for them in Selukwe.[39] Jacob Smit's Liberals, despite their name, were decidedly illiberal, chiefly representing commercial farming, mining and industrial interests.[40] Smith, initially reluctant, said he was too busy organising his life to stand, but agreed after one of the Liberal officials suggested that a political career might allow him to defend the values he had fought for in the Second World War.[41] With their wedding barely a fortnight away, Janet was astonished to learn of Smith's decision to run for parliament, having never before heard him discuss politics. "I can't say that I am really interested in party politics," Smith explained to her, "but I've always been most interested in sound government."[42] Smith duly became a Liberal Party politician, finalised his purchase of Gwenoro, and married Janet, adopting her two children as his own, all in a few weeks in August 1948. They enjoyed a few days' honeymoon at Victoria Falls, then went straight into the election campaign.[42]

The Southern Rhodesian electoral system allowed only those who met certain financial and educational qualifications to vote. The criteria applied equally to all regardless of race, but since most black citizens did not meet the set standards, the electoral roll and the colonial parliament were overwhelmingly white.[43] Smith canvassed around the geographically very large Selukwe constituency and quickly won considerable popularity. Many white families were receptive to him because of their respect for his father, or because they had had children at school with him. His RAF service also helped, particularly as the local United Party candidate, Petrus Cilliers, had been interned during the hostilities for opposing the war effort.[44] On 15 September 1948, Smith defeated Cilliers and the Labour candidate Egon Klifborg with 361 votes out of 747, and thereby became Member of Parliament for Selukwe.[45] At 29 years old, he was the youngest MP in Southern Rhodesian history.[46] The Liberals as a party, however, were roundly defeated, going from 12 seats before the election to only five afterwards. Jacob Smit, who had lost his seat in Salisbury City,[45] retired and was replaced as Leader of the Opposition by Raymond Stockil, who renamed the Liberals the "Rhodesia Party".[46] Having grown up in an area of Cape Town so pro-Smuts that she had never had to vote, Janet did not think her husband's entry to parliament would alter their lives at all. "First of all I was marrying a farmer," she later said, "now he was going to be a politician as well. So I said, 'Well, if you are really interested in it, carry on.'... It never dawned on me—being so naive about politicians—that our lives would be affected in the slightest degree."[47]

Parliament

[edit]Backbencher

[edit]

Because of Southern Rhodesia's small size and lack of major controversies, its unicameral parliament then sat only twice a year, for about three months in total, holding discussions in the afternoons either side of a half-hour break for tea on the lawn.[48] Smith's early parliamentary commitments in Salisbury therefore did not detract greatly from his ranching. His maiden speech to the Legislative Assembly, in November 1948, concerned the Union of South Africa Trade Agreement Bill, then at its second reading. He was slow to make an impact in parliament—most of his early contributions related to farming and mining—but his exertions within the party won him Stockil's respect and confidence.[46] Janet ran Gwenoro during Smith's absences,[49] and gave birth to his only biological child, Alec, in Gwelo on 20 May 1949.[50] Smith also served as a Presbyterian elder.[51]

The pursuit of full dominion status was then regarded as something of a non-issue by most Southern Rhodesian politicians. They viewed themselves as virtually independent already; they lacked only the foreign affairs portfolio and taking this on would mean having to shoulder the expense for high commissions and embassies overseas.[52] Huggins and the United Party instead pursued an initially semi-independent Federation with Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, two protectorates directly administered from London,[53] with the hope of ultimately creating a single, united dominion in south-central Africa.[n 7]

Smith was one of the few to raise the independence issue at this time, according to his memoirs because his "instinct and training told me to be prepared for every contingency".[55] During the Federation debate in the House of Assembly, he posited that since Southern Rhodesia was effectively choosing Federation over independence, a clause should be inserted into the bill guaranteeing Southern Rhodesia dominion status in the event of a Federal break-up. The United Party rejected this on the grounds that the Federation had to be declared indissoluble so it could raise loans.[55] Smith was uncertain about the Federal project, but publicly supported it after the mostly white electorate approved it in a referendum in April 1953. He told the Rhodesia Herald that now it had been decided to pursue Federation, it was in Southern Rhodesia's best interests for everybody to try to make it succeed.[56] He and other Rhodesia Party politicians joined the new Federal Party, headed by Huggins and Northern Rhodesia's Welensky, on 29 April 1953.[57]

Federation; Chief Whip

[edit]

The Federation was overtly led by Southern Rhodesia, the most developed of the three territories—Salisbury was its capital and Huggins its first prime minister. Garfield Todd replaced Huggins as Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia. Resigning his Selukwe seat, Smith contested and won the Federal Assembly's Midlands constituency in the inaugural Federal election on 15 December 1953,[57] and thereafter continued as a backbench member of little distinction. In the recollection of Welensky, who took over as Federal Prime Minister on Huggins's retirement in 1956, Smith "didn't spend much time in Salisbury" during the early Federal period, and had "three major interests ... one was daylight saving, one was European education and he always showed an interest in farming".[58]

Smith received his first political office in November 1958, following that month's Federal election (in which he was returned as MP for Gwanda), after one of Welensky's Federal Cabinet ministers requested Smith's appointment as a Parliamentary Secretary in the new United Federal Party (UFP) government. Welensky turned this down, saying that while he appreciated Smith's relative seniority on the back benches after 10 years in parliament, he did not think he had "shown the particular drive that I would have expected" for such a role.[59] He decided to instead give Smith "a run as Chief Whip, which is generally the step to a ministerial appointment, and ... see how he works out".[59]

According to his biographer Phillippa Berlyn, Smith remained a somewhat pedestrian figure as Chief Whip, though he was acknowledged by his peers as someone who "did his homework well" whenever he contributed.[60] Clifford Dupont, then Smith's counterpart as Chief Whip of the Dominion Party, later commented that the UFP's huge majority in the Federal Assembly gave Smith little opportunity to distinguish himself, as few votes were ever in serious doubt.[60]

Leaving the UFP

[edit]

Amid decolonisation and the Wind of Change, the idea of "no independence before majority rule" ("NIBMAR") gained considerable ground in British political circles during the late 1950s and early 1960s. The Federation, which had faced black opposition from the start, particularly in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, grew ever more tenuous.[61] Despite Todd's lowering of Southern Rhodesia's educational and financial voting qualifications in 1957 to enlarge the black electorate, very few of the newly enfranchised blacks registered to vote, much less utilised their vote, partly due to a boycott campaign by black nationalist movements seeking majority rule. This boycott saw the movement's first violent actions take place; black people suspected of registering to vote or participating in the vote were subject to arson attacks and petrol bombings.[62][n 8] Attempting to advance the case for Southern Rhodesian independence, particularly in the event of Federal dissolution,[64] Sir Edgar Whitehead, who replaced Todd in 1958, agreed to a new constitution with Britain in 1961.[65] The 1961 constitution contained no explicit independence guarantees, but Whitehead, Welensky and other proponents nevertheless presented it to the Southern Rhodesian electorate as the "independence constitution" under which Southern Rhodesia would become a Commonwealth realm, on a par with Australia, Canada and New Zealand, if the Federation broke up.[66]

Smith was one of the loudest voices of white dissent against the new constitution: alongside its lack of guarantees for eventual independence,[67] he opposed its splitting of the qualified electorate (which was formally non-racial but which had resulted in a low percentage of blacks being eligible to vote) into graduated "A" and "B" rolls (the latter having lower income and property qualifications), saying that the proposed system had "racialist" connotations,[68] and objected to the idea that the first black MPs would be elected on what he said would be a "debased franchise".[69][n 9] Steadfastly holding onto a view that the electorate should be decided by qualifications rather than by universal suffrage, he stated that "our policy in the past has always been that we would have a government, in Rhodesia, based on merit and that people wouldn't worry whether you were black or whether you were white,"; either way, most blacks did not qualify for either roll in the subsequent election.[71] At the UFP vote on the constitution on 22 February 1961, Smith was the only member out of 280 to vote against it.[n 10] Deeply disillusioned by these developments, he resigned from the UFP soon thereafter to sit in the Federal Assembly as an independent. He lent his support to the "United Group", an awkward coalition wherein Winston Field's conservative Dominion Party closed ranks with Sir Robert Tredgold and other liberals against the constitutional proposals, despite opposing them for totally contradictory reasons.[66] The black-nationalist leaders initially endorsed the constitution, signing the draft document, but repudiated it almost immediately thereafter and called for blacks to boycott elections held under it.[72] A referendum of the mostly white electorate approved the new constitution by a majority of 65% on 26 July 1961.[73]

Forming the Rhodesian Front

[edit]As the UK government granted majority rule in Nyasaland and made moves towards the same in Northern Rhodesia, Smith decided that the Federation was a lost cause and resolved to found a new party that would push for Southern Rhodesian independence without acquiescing to British demands. With the support of the rancher, miner and industrialist Douglas "Boss" Lilford, he formed the Rhodesian Reform Party (RRP), based around defectors from the UFP, in December 1961.[74] Meanwhile, Whitehead attempted to counter the black nationalists and persuade newly eligible blacks to register as voters. He banned the main nationalist group, the National Democratic Party, for being violent and intimidatory—it reformed overnight as the Zimbabwe African People's Union[n 11]—and announced that the UFP would repeal the racially discriminatory Land Apportionment Act of 1930 if it won the next election, as an attempt to appeal to newly enfranchised blacks.[77] These actions gained few black votes, but prompted many scandalised whites to defect to the RRP or Field's Dominion Party.[78]

Smith, Field and others met in Salisbury on 13 March 1962 and agreed to unite against Whitehead as the Rhodesian Front (RF). The Front ranged from former UFP members, including Smith, who advocated gradual transition and a government based on merit and electoral qualifications, to the Dominion Party's more right-wing members, some of whom held explicitly segregationist views not dissimilar to those of South Africa's National Party. Amid these differences, the nascent RF coalition was shaky at best. Its members were brought together by their common opposition to Whitehead's promises of fast-track reform, which they agreed would lead to a Congo-style national crisis, the flight of the white community and ultimately the country's destruction.[79] In the wider Cold War context, the ardently anti-communist RF aspired to represent a pro-Western bulwark in Africa, alongside South Africa and Portugal, in the face of what they saw as Soviet and Chinese expansionism.[80] Smith asserted that the RF worked to thwart "this mad idea of a hand-over, of a sell-out of the European and his civilisation, indeed of everything he had put into his country".[79] "The white man is the master of Rhodesia," he declared; "[he] has built it and intends to keep it".[81]

The RF ignored the April 1962 Federal elections, deeming them irrelevant, and instead concentrated on the Southern Rhodesian elections that were due at the end of the year.[79] Whitehead attempted to curb the continuing black-nationalist violence through new legislation and in September 1962 banned ZAPU, arresting 1,094 of its members and describing it as a "terrorist organisation",[82] but he was still seen by much of the electorate as too liberal. He set a general election for 14 December 1962. A number of corporations that had previously funded UFP campaigning this time backed the RF. The RF campaign exploited the chaos in the Congo and the uncertainty regarding Southern Rhodesia's future to create a theme of urgency—it pledged to keep power "in responsible hands", to defend the Land Apportionment Act, to oppose compulsory integration, and to win Southern Rhodesian independence.[83]

The electoral race was close-run until the night before election day, when Whitehead made what proved a fatal political gaffe by telling a public meeting at Marandellas that he would appoint a black Cabinet minister immediately if he won the election, and might soon have as many as six. This statement appeared on the radio news just before the polling booths opened the next morning, and stunned white voters. Many abandoned Whitehead at the last minute.[84] The results, announced on 15 December 1962, put the RF into government with 35 "A"-roll seats to the UFP's 15 "A"-roll and 14 "B"-roll seats.[n 12] Few had expected this; even the RF was somewhat taken aback by its victory,[85] though Smith later described feeling "quietly confident" on election day.[86] Contesting the Umzingwane constituency in the rural south-west, he bested the UFP's Reginald Segar by 803 votes to 546.[87]

Deputy Prime Minister under Field

[edit]Announcing his Cabinet on 17 December 1962, Field named Smith his deputy prime minister and Minister of the Treasury.[88][71] Two days later, R.A. Butler, the UK's Deputy Prime Minister and First Secretary of State, announced that the UK government would allow Nyasaland to leave the Federation.[n 13] With Northern Rhodesia now also under a secessionist black-nationalist government—Kenneth Kaunda and Harry Nkumbula had formed a coalition to keep the UFP out—and Southern Rhodesia under the RF, the Federation was effectively over.[90] The Field Cabinet made Southern Rhodesian independence on Federal dissolution its first priority,[90] but the Conservative government in the UK was reluctant to grant this under the 1961 constitution as it knew doing so would lead to censure and loss of prestige in the United Nations (UN) and the Commonwealth.[91] Indeed, Southern Rhodesia's minority government had already become something of an embarrassment to the UK and it hurt Britain's reputation to even maintain the status quo there.[92] Granting independence without major constitutional reform would furthermore provoke outcry from the Conservatives' main parliamentary opposition, the Labour Party, which was strongly anti-colonial and supportive of black-nationalist ambitions.[93]

Butler announced on 6 March 1963 that he was going to convene a conference to decide the Federation's future. It would be impossible (or at least very difficult) for the UK to dissolve the union without Southern Rhodesia's co-operation as the latter, being self-governing, had been co-signatory to the Federal agreement in 1953.[94] According to Smith, Field, Dupont and other RF politicians, Butler made several oral independence guarantees to ensure Southern Rhodesia's attendance and support at the conference, but repeatedly refused to give anything on paper.[n 14] Field and Smith claimed that Butler justified this to them the day before the conference began by saying that binding Whitehall to a document rather than his word would be against the Commonwealth's "spirit of trust"—an argument that Field eventually accepted. "Let's remember the trust you emphasised," Smith warned, according to Field's account wagging his finger at Butler; "if you break that you will live to regret it."[96] No minutes were made of this meeting. Butler denied afterwards that he had ever made such a promise.[96] Southern Rhodesia attended the conference, held at the Victoria Falls Hotel over a week starting from 28 June 1963, and among other things it was agreed to formally liquidate the Federation at the end of 1963.[97]

The Federation dissolved on 31 December 1963 with Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia both on track for full statehood by the end of 1964, while Southern Rhodesia continued to drift in uncertainty. Under huge pressure from the RF to rectify this matter and win independence, Field's perceived vacillation and timidness in his dealings with the UK government caused sections of his party to lose confidence in him during early 1964.[98] On 2 April 1964, with Smith in the chair, the RF caucus passed a near-unanimous vote of no confidence in Field, leading to the Prime Minister's resignation 11 days later. Smith accepted the Cabinet's nomination to take his place.[99] He was the first Southern Rhodesian prime minister to have been born in the country,[n 15] something that he thought profoundly altered the character of the dispute with Britain. "For the first time in its history the country now had a Rhodesian-born PM, someone whose roots were not in Britain, but in southern Africa," he later reflected—"in other words, a white African."[101]

Prime minister

[edit]First days; banning of PCC/ZAPU and ZANU

[edit]

Most of the Southern Rhodesian press predicted that Smith would not last long; one column called him "a momentary man", thrust into the spotlight by the RF's dearth of proven leaders. His only real rival to replace Field had been William Harper, an ardent segregationist who had headed the Dominion Party's Southern Rhodesian branch during the Federal years.[102] Some reporters predicted Welensky's imminent introduction to Southern Rhodesian politics at the head of an RF–UFP coalition government, but Welensky showed little interest in this idea, saying he would be unable to manoeuvre in an RF-dominated House.[103] The RF's replacement of Field with Smith drew criticism from the British Labour leader Harold Wilson, who called it "brutal",[104] while John Johnston, the British High Commissioner in Salisbury, indicated his disapproval by refusing to meet Smith for two weeks after he took office.[103] The ZAPU leader Joshua Nkomo branded the new Smith Cabinet "a suicide squad ... interested not in the welfare of all the people but only in their own", and predicted that the RF would "eventually destroy themselves".[105] Asserting that a lasting "place for the white man" in Southern Rhodesia would benefit all of the country's people, the new prime minister said the government should be based "on merit, not on colour or nationalism",[106] and insisted that there would be "no African nationalist government here in my lifetime".[107]

Smith announced his Cabinet on his first day in office, 14 April 1964. He increased the number of ministers from 10 to 11, redistributed portfolios, and made three new appointments.[n 16] Smith's fellow former UFP men made up most of the new RF Cabinet, with Harper and the Minister of Agriculture, James Graham, 7th Duke of Montrose (also called Lord Graham), heading a minority of hardline Dominion Party veterans. Ken Flower, whom Field had appointed Director of the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) on its creation the previous year, was surprised to be retained by Smith.[102] Smith announced his policies to the nation through full-page advertisements in the newspapers: "No forced integration. No lowering of standards. No abdication of responsible government. No repeal of the Land Apportionment Act. No appeasement to suit the Afro-Asian bloc."[108] "An honest Rhodesian," a 1964 political poster declared—"Trust Mr Smith. He will never hand over Rhodesia."[109] Smith retained the post of Minister of External Affairs to himself.[88]

One of the Smith government's first actions was to crack down hard on the black-nationalist political violence that had erupted following the establishment of a second black-nationalist organisation, the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), by disgruntled ZAPU members in Tanzania in August 1963.[n 17] The rival movements were split tribally, ZAPU being mostly Ndebele and ZANU predominantly Shona, and politically—ZAPU, which had relabelled itself the People's Caretaker Council (PCC) within Southern Rhodesia to circumvent its ban, was Marxist–Leninist and backed by the Warsaw Pact and its allies, while ZANU had aligned itself with Maoism and the bloc headed by communist China.[111] Their respective supporters in the black townships clashed constantly, also targeting non-aligned blacks whom they hoped to recruit, and sporadically attacked whites, businesses and police stations.[112]

Amid PCC/ZAPU's calls for various strikes and protests, including an appeal for black children to boycott state schools, Smith's Justice Minister Clifford Dupont had Nkomo and other PCC/ZAPU leaders restricted at Gonakudzingwa in the remote south-east two days after Smith took office.[113] The politically motivated killing of a white man, Petrus Oberholzer, near Melsetter by ZANU insurgents on 4 July 1964 marked the start of intensified black-nationalist violence and police counteraction that culminated in the banning of ZANU and PCC/ZAPU on 26 August, with most of the two movements' respective leaders concurrently jailed or restricted.[114] ZANU, ZAPU and their respective guerrilla armies—the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) and the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA)—thereafter operated from abroad.[115]

Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI)

[edit]

Smith, who had been to the UK only four times before 1964 and never more than briefly, was soon labelled a "raw colonial" by Whitehall.[116] He was almost immediately engaged in a dispute with the UK government, which he claimed had forsaken British ideals, and the Commonwealth, which he said had abandoned its own founding principles amid the Wind of Change. He accused both of isolating Southern Rhodesia because it still respected these values.[117] When he learned in June that Salisbury would not be represented at the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference for the first time since 1932, he was deeply insulted and alleged British betrayal, double standards and appeasement.[n 18] Three months later, Smith accepted the British condition that the independence terms had to be acceptable to majority opinion, but impasse immediately developed regarding the mechanism by which black views would be gauged.[n 19] Labour's narrow victory in the October 1964 UK general election meant that Smith would be negotiating not with Douglas-Home but with Harold Wilson, who was far less accommodating towards the RF stand.[120] Smith declared acceptability to majority opinion to have been demonstrated after a largely white referendum and an indaba of tribal chiefs and headmen both decisively backed independence under the 1961 constitution in October and November 1964,[n 20] but black nationalists and the UK government dismissed the indaba as insufficiently representative of the black community.[122]

Following Northern Rhodesia's independence as Zambia in October 1964—Nyasaland had been independent Malawi since July—Southern Rhodesia began referring to itself simply as Rhodesia, but Whitehall rejected this change.[n 21] Perceiving Smith to be on the verge of a unilateral declaration of independence (UDI), Wilson issued a statement in October 1964 warning of dire economic and political consequences, and wrote to Smith demanding "a categorical assurance forthwith" that no UDI would be attempted. Smith ignored this, expressing confusion as to what he had done to provoke it.[125] The UK and Rhodesian governments exchanged often confrontational correspondence over the next year or so, each accusing the other of being unreasonable and intransigent.[126] Little progress was made when two prime ministers met in person in January 1965, when Smith travelled to London for Sir Winston Churchill's funeral.[127] The RF called a fresh election for May 1965 and, campaigning on an election promise of independence, won all 50 "A"-roll seats (elected mostly by whites).[n 22] Wilson's ministers deliberately stonewalled Smith during mid-1965, hoping to eventually break him down, but this only caused the Rhodesian hierarchy to feel yet more alienated.[129] From June, a peripheral dispute concerned Rhodesia's unilateral and ultimately successful attempt to open an independent mission in Lisbon; Portugal's acceptance of this in September 1965 prompted British outrage and Rhodesian delight.[130]

Amid rumours that UDI was imminent, Smith arrived in London on 4 October 1965 with the declared intent of settling the independence issue,[131] but flew home eight days later with the matter unresolved.[132] When Wilson travelled to Salisbury on 26 October, Smith offered to enfranchise about half a million black Rhodesians immediately along the lines of "one taxpayer, one vote" in return for independence,[133] but Wilson said this was unacceptable as most blacks would still be excluded. He proposed a Royal Commission to test public opinion in Rhodesia regarding independence under the 1961 constitution, and suggested that the UK might safeguard black representation in the Rhodesian parliament by withdrawing relevant devolved powers. This latter prospect horrified Smith's team as it seemed to them to have ruled out the failsafe option of keeping the status quo. After Wilson returned to Britain on 30 October 1965,[134] he presented terms for the Royal Commission that the Rhodesians found unacceptable—among other things, Britain would not commit itself to accepting the results. Smith rejected these conditions on 5 November, saying they made the whole exercise pointless.[135] After waiting a few days for new terms from Wilson,[136] Smith made a consensus decision with his Cabinet to break ties unilaterally on 11 November 1965, and signed the Unilateral Declaration of Independence at 11:00 local time.[137]

Fallout from UDI

[edit]UDI, while received calmly by most Rhodesians, prompted political outrage in the UK and overseas.[138] It astonished Wilson, who called on the people of Rhodesia to ignore the post-UDI government, which he described as "hell-bent on illegal self-destroying".[139] Following orders from Whitehall and the passage of the Southern Rhodesia Act 1965, the colonial Governor Sir Humphrey Gibbs formally sacked Smith and his Cabinet, accusing them of treason. Smith and his ministers ignored this, considering Gibbs's office obsolete under the 1965 constitution enacted as part of UDI.[138][n 23] After Gibbs made clear that he would not resign, Smith's government effectively replaced him with Dupont, who was appointed to the post of "Officer Administering the Government" (created by the 1965 constitution). No attempt was made to remove Gibbs from his official residence at Government House opposite Smith's residence at Independence House, however; Gibbs remained there, ignored by the Smith administration, until the declaration of a republic in 1970.[3]

Smith and his government initially continued to profess loyalty to Queen Elizabeth II. The 1965 Constitution reconstituted Rhodesia as a Commonwealth realm, with Elizabeth II as "Queen of Rhodesia". Indeed, the UDI document ended with the words "God Save The Queen". In December 1965, Smith, attempting to assert the rights he claimed as Her Majesty's Rhodesian prime minister, wrote a letter to Elizabeth asking her to appoint Dupont as governor-general of Rhodesia.[141] The Queen rejected Smith's letter, which she characterised in her response as "purported advice".[142] The UK, with the near-unanimous support of the international community, maintained that Gibbs was now Elizabeth II's only legitimate representative in what it still reckoned as the colony of Southern Rhodesia, and hence the sole lawful authority there.[3]

The UN General Assembly and Security Council quickly joined the UK in condemning UDI as illegal and racist. Security Council Resolutions 216 and 217, adopted in the days following Smith's declaration, denounced UDI as an illegitimate "usurpation of power by a racist settler minority", and called on nations not to entertain diplomatic or economic relations.[143] No country recognised Rhodesia as independent.[144] Black nationalists in Rhodesia and their overseas backers, prominently the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), clamoured for the UK to remove Smith's government with a military invasion, but Britain dismissed this option, citing logistical issues, the risk of provoking a pre-emptive Rhodesian strike on Zambia, and the psychological issues likely to accompany any confrontation between British and Rhodesian troops.[145] Wilson instead resolved to end UDI through economic sanctions, banning the supply of oil to Rhodesia and the import of most Rhodesian goods to Britain. When Smith continued to receive oil through South Africa and Portuguese Mozambique, Wilson posted a Royal Navy squadron to the Mozambique Channel in March 1966. This blockade, the Beira Patrol, was endorsed by UN Security Council Resolution 221 the following month.[146]

Wilson predicted in January 1966 that the various boycotts would force Smith to give in "within a matter of weeks rather than months",[147] but the British (and later UN) sanctions had little effect on Rhodesia, largely because South Africa and Portugal went on trading with it, providing it with oil and other key resources.[148] Clandestine trade with other nations also continued, initially at a reduced level, and the diminished presence of foreign competitors helped domestic industries to slowly mature and expand.[149] Even many OAU states, while bombarding Rhodesia with opprobrium, continued importing Rhodesian food and other products.[150] Rhodesia thus avoided the economic cataclysm predicted by Wilson and gradually became more self-sufficient.[149] "Rhodesia can not only take it, but she can also make it," Smith said on 29 April 1966, while opening the annual Central African Trade Fair in Bulawayo. "When I say take it, I use it in two ways. Firstly, when it comes to sanctions we have proved we can take it. Secondly, when it comes to independence, we have also proved we can take it."[151]

Meanwhile, throughout the 1960s and '70s, Smith hired pseudoarchaeologists with the aim to preserve the myth that Great Zimbabwe was the product of a mysterious foreign civilisation. His government forced Peter Garlake, who argued that it was the work of the Karanga (south-central Shona), into exile.[152]

Tiger and Fearless talks with Wilson

[edit]

Wilson told the UK's House of Commons in January 1966 that he would not enter any kind of dialogue with Smith's post-UDI government (which he called "the illegal regime") until it gave up its claim of independence,[153] but by mid-1966 British and Rhodesian civil servants were holding "talks about talks" in London and Salisbury.[154] By November that year, Wilson had agreed to negotiate personally with Smith.[155] Smith and Wilson subsequently held two rounds of direct negotiations, both of which were held aboard Royal Navy ships off Gibraltar. The first took place aboard HMS Tiger between 2 and 4 December 1966,[156] while the second, aboard HMS Fearless, was held between 8 and 13 October 1968.[157]

The UK's prime minister went to HMS Tiger in a belligerent mindset. Wilson's political secretary Marcia Falkender later wrote of "apartheid ... on that ship",[158] with the British and Rhodesian delegations separated in all activities outside the conference room at Wilson's orders.[n 24] Despite the uneasy atmosphere—accounts from both sides describe Wilson dealing with the Rhodesians extremely tersely[160]—talks progressed relatively smoothly until the subject turned to the manner of the transition. Wilson insisted on the abandonment of the 1965 constitution, the dissolution of the post-UDI government in favour of a "broad-based" multiracial interim administration and a period under a British governor, conditions that Smith saw as tantamount to surrender, particularly as the UK proposed to draft and introduce the new constitution only after a fresh test of opinion under UK control. When Smith asserted on 3 December that he could not settle without first consulting his Cabinet in Salisbury, Wilson was enraged, declaring that a central condition of the summit had been that he and Smith would have plenipotentiary powers to make a deal.[161][n 25] According to J.R.T. Wood, Wilson and his Attorney General Sir Elwyn Jones then "bullied Smith for two long days" to try to get him to settle, without success.[163]

A working document was ultimately produced and signed by Smith, Wilson and Gibbs, to be accepted or rejected in its entirety by each Cabinet after the Prime Ministers returned home. Whitehall accepted the proposals, but Salisbury turned them down; Smith announced on 5 December 1966 that while he and his ministers were largely satisfied with the terms, the Cabinet did not feel it could responsibly abandon the 1965 constitution while so much uncertainty surrounded the transition and the new "mythical constitution yet to be evolved".[164] Rhodesia's Leader of the Opposition Josiah Gondo promptly demanded Smith's resignation, reasoning that the Cabinet's rejection of the working document he had helped to draft amounted to a vote of no confidence. The RF ignored him.[165] Warning that "grave actions must follow",[165] Wilson took the Rhodesia problem to the United Nations, which proceeded to institute the first mandatory trade sanctions in its history with Security Council Resolutions 232 (December 1966) and 253 (April 1968). These measures required UN member states to prevent all trade and economic links with Rhodesia.[166]

State press censorship, introduced by the Smith administration on UDI, was lifted in early April 1968,[167] though according to the Glasgow Herald the government retained "considerable powers to control information. It may reflect no more than Mr Smith's growing confidence that nothing—short of a sell-out to Britain—can undermine his position in Rhodesia".[168] The series of Rhodesian High Court cases debating the legality of UDI came to a close five months later on 13 September. A panel of judges headed by Sir Hugh Beadle ruled UDI, the 1965 constitution and Smith's government to be de jure,[n 26] prompting the UK Commonwealth Secretary George Thomson to accuse them of breaching "the fundamental laws of the land".[170]

On HMS Fearless, the UK reversed its confrontational approach of the Tiger talks and made a marked effort to appear genial and welcoming, mixing socially with the Rhodesians and accommodating Smith in the Admiral's cabin on HMS Kent, which was moored alongside.[171] Marked progress towards agreement was made—for example, Wilson dropped altogether the transition period under a colonial governor—but the Rhodesian delegation now demurred on a new British proposal, the "double safeguard". This would involve elected black Rhodesians controlling a blocking quarter in the Rhodesian parliament, and thereafter having the right to appeal passed legislation to the Privy Council in London. Smith's team accepted the principle of the blocking quarter but agreement could not be reached on the technicalities of it;[172] the involvement of the UK Privy Council was rejected by Smith as a "ridiculous" provision that would prejudice Rhodesia's sovereignty.[173] The Fearless summit ended with a joint Anglo-Rhodesian statement asserting that "both sides recognise that a very wide gulf still remains", but were prepared to continue negotiations in Salisbury. This never occurred.[173]

A republic; failed accord with Douglas-Home

[edit]With their hopes of Commonwealth realm status through a settlement with Britain dimming, Smith and the RF began to seriously consider the alternative of a republic as early as December 1966, after the Tiger talks.[175] Republicanism was presented as a means to clarify Rhodesia's claimed constitutional status, end ambiguity regarding ties with Britain and elicit official foreign recognition and acceptance.[144] Smith's government began exploring a republican constitution in March 1967.[176] The Union Jack and Rhodesia's Commonwealth-style national flag—a defaced Sky Blue Ensign with the Union Jack in the canton—were formally superseded on 11 November 1968, the third anniversary of UDI, by a new national flag: a green-white-green vertical triband, charged centrally with the Rhodesian coat of arms.[177] After the electorate voted "yes" in a June 1969 referendum both to a new constitution and to the abandoning of symbolic ties to the Crown, Smith declared Rhodesia a republic on 2 March 1970. The 1969 constitution introduced a president as head of state, a multiracial senate, separate black and white electoral rolls (each with qualifications) and a mechanism whereby the number of black MPs would increase in line with the proportion of income tax revenues paid by black citizens. This process would stop once blacks had the same number of seats as whites; the declared goal was not majority rule, but rather "parity between the races".[176]

No country recognised the Rhodesian republic.[144] The RF was decisively returned to power in the first election held as a republic, on 10 April 1970, winning all 50 white seats.[178] Hopes for an Anglo-Rhodesian rapprochement were boosted two months later when the Conservatives won a surprise election victory in the UK. Edward Heath took over as prime minister while Douglas-Home became Foreign Secretary. Talks between Douglas-Home and Smith began with a lengthy meeting in Salisbury in April 1971 and continued until a tentative understanding was reached in early November. A UK delegation headed by Douglas-Home and the Attorney General Sir Peter Rawlinson flew to Salisbury on 15 November for negotiations over a new constitution, and after six days of discussion an accord was signed on 21 November 1971.[179]

The constitution agreed upon was based largely on the one Rhodesia had just adopted, but would eventually bring about a black majority in parliament. Black representation in the House would be immediately increased, and a majority of both black and white MPs would have to approve retrogressive legislation; blacks would thus wield an effective veto "as long as they voted solidly together", Robert Blake comments.[180] "The principle of majority rule was enshrined with safeguards ensuring that there could be no legislation which could impede this," Smith wrote in his memoirs. "On the other hand, there would be no mad rush into one man, one vote with all the resultant corruption, nepotism, chaos and economic disaster which we had witnessed in all the countries around us."[181]

The UK announced a test of opinion in Rhodesia to be undertaken by a four-man commission headed by the veteran judge Lord Pearce.[n 28] All four population groups—black, white, coloured (mixed) and Asian—would have to approve the terms for Britain to proceed. ZANU and ZAPU supporters quickly formed the African National Council (later the United African National Council, or UANC) to organise and co-ordinate black opposition to the deal. Bishop Abel Muzorewa, the first black man to have been ordained as such in Rhodesia, was installed as the movement's leader.[183] The Pearce Commission finished its work on 12 March 1972 and published its report two months later—it described white, coloured and Asian Rhodesians as in favour of the terms by 98%, 97% and 96% respectively, and black citizens as against them by an unspecified large majority.[184] This came as a great shock to the white community "and a deep disappointment to those in Britain who hoped to get rid of this tiresome albatross", Blake records.[185] Smith condemned the Pearce Commissioners as "naive and inept".[186][n 29] The UK withdrew from negotiations,[185] but neither government abandoned the accord entirely. "I would ask them [the black people of Rhodesia] to look again very carefully at what they rejected," Douglas-Home told the House of Commons; "the proposals are still available because Mr Smith has not withdrawn or modified them."[188]

Bush War

[edit]

The Rhodesian Bush War (or Second Chimurenga), which had been underway at a low level since before UDI, began in earnest in December 1972 when ZANLA attacked farms in north-eastern Rhodesia.[189] The Rhodesian Security Forces mounted a strong counter-campaign over the next two years.[190] Muzorewa re-engaged with Smith in August 1973, accepting the 1971–72 Douglas-Home terms, and the two signed a statement to that effect on 17 August.[191] The UANC executive repudiated this in May 1974, but talks between Smith and Muzorewa continued sporadically.[191] The RF again won a clean sweep of the 50 white seats in the July 1974 general election.[192]

Rhodesia's early counter-insurgency successes were undone by political shifts in the guerrillas' favour overseas. The April 1974 Carnation Revolution in Lisbon led to Mozambique's transformation over the next year from a Portuguese territory friendly to Smith's government into a communist state openly allied with ZANU.[193] Wilson and Labour returned to power in the UK in March 1974.[194] Portugal's withdrawal made Rhodesia hugely dependent on South Africa,[195] but Smith still insisted that he held a strong position. "If it takes one year, five years, ten years, we're prepared to ride it out," he told the RF congress on 20 September 1974. "Our stand is clear and unambiguous. Settlement is desirable, but only on our terms."[196]

The geopolitical situation tilted further against Smith in December 1974 when the South African Prime Minister B. J. Vorster pressured him into accepting a détente initiative involving the Frontline States of Zambia, Tanzania and Botswana (Mozambique and Angola would join the following year).[197] Vorster had concluded that Rhodesia's position was untenable; in his view, it made no sense to maintain white rule in a country where blacks outnumbered whites by 22:1.[198] He also believed that South African interests would be better served by collaborating with black African governments over a Rhodesian settlement; he hoped that success in this might win South Africa some international legitimacy and allow it to retain apartheid.[199] Détente forced a ceasefire, giving the guerrillas time to regroup, and required the Rhodesians to release the ZANU and ZAPU leaders so they could attend a conference in Rhodesia, united under the UANC banner and led by Muzorewa.[200] When Rhodesia stopped releasing black-nationalist prisoners on the grounds that ZANLA and ZIPRA were not observing the ceasefire, Vorster harried Smith further by withdrawing the South African Police, which had been helping the Rhodesians patrol the countryside.[193][n 30] Smith remained stubborn, saying in the run-up to the conference that "We have no policy in Rhodesia to hand over to a black majority government" and that his government instead favoured "a qualified franchise for all Rhodesians ... [to] ensure that government will be retained in responsible hands for all times".[202]

Nkomo remained unchallenged at the head of ZAPU, but the ZANU leadership had become contested between its founding president, the Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole, and Robert Mugabe, a former teacher from Mashonaland who had recently won an internal election in prison. When they were released in December 1974 under the détente terms, Mugabe went to Mozambique to consolidate his leadership of the guerrillas, while Sithole joined Muzorewa's delegation.[193] It had been agreed that the talks would take place within Rhodesia, but the black nationalists refused to meet on ground they perceived as not neutral. The Rhodesians insisted on abiding by the accord and negotiating inside the country. To please both camps the conference was held on a train halfway across the Victoria Falls Bridge on the border between Rhodesia and Zambia; the delegations sat on opposite sides of the frontier. The conference, which took place on 26 August 1975 with Kaunda and Vorster as mediators, failed to produce a settlement; each side accused the other of being unreasonable.[203] Smith afterwards held direct talks with Nkomo and ZAPU in Salisbury, but these also led nowhere; Nkomo proposed an immediate transition to an interim government headed by himself, which Smith rejected.[204] Guerrilla incursions picked up strongly in the first months of 1976.[205]

On 20 March 1976, Smith gave a televised speech including what became his most quoted utterance. "I don't believe in majority rule ever in Rhodesia—not in 1,000 years," he said. "I repeat that I believe in blacks and whites working together. If one day it is white and the next day it is black, I believe we have failed and it will be a disaster for Rhodesia."[206] The first sentence of this statement became commonly quoted as evidence that Smith was a crude racist who would never compromise with the black nationalists, even though the speech was one in which Smith had said that power-sharing with black Rhodesians was inevitable and that "we have got to accept that in the future Rhodesia is a country for black and white, not white as opposed to black and vice versa".[206][207] The "not in 1,000 years" comment was, according to Peter Godwin, an attempt to reassure the RF's right wing, which opposed any transition whatsoever, that white Rhodesians would not be sold out.[206] In her 1978 biography of Smith, Berlyn comments that regardless of whether the statement was "taken out of context, or whether his actual intent was misinterpreted", this was one of his greatest blunders as prime minister as it gave obvious ammunition to his detractors.[208]

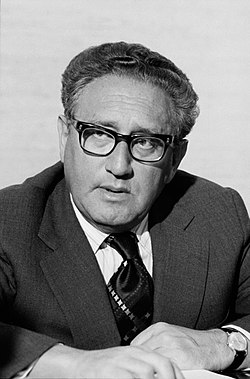

Henry Kissinger, the U.S. Secretary of State, announced a formal interest in the Rhodesian situation in February 1976, and over the next half-year held discussions with the United Kingdom, South Africa and the Frontline States in what became the "Anglo-American initiative".[209] Meeting Smith in Pretoria on 18 September 1976, Kissinger proposed majority rule after a transition period of two years.[210] He strongly encouraged Smith to accept his deal, though he knew it was unpalatable to him, as any future offer could only be worse from Smith's standpoint—especially if, as expected, U.S. president Gerald Ford lost the upcoming election to Jimmy Carter. Smith expressed great reluctance, but agreed on 24 September after Vorster intimated that South Africa might cut off financial and military aid if he refused.[211] It was the first time Smith had publicly accepted the principles of unconditional majority rule and one man, one vote.[209] However, the Frontline States then abruptly revised their stance and turned the Kissinger terms down, saying that any transition period was unacceptable. The UK quickly arranged an all-party conference in Geneva, Switzerland to try to salvage a solution.[212] ZANU and ZAPU announced that they would attend this and any summit thereafter as a joint "Patriotic Front" (PF), including members of both parties under a combined leadership. The Geneva Conference, held between October and December 1976 under British mediation, also failed.[213]

Internal Settlement and Lancaster House; becoming Zimbabwe

[edit]

Smith's moves towards a settlement with black-nationalist groups prompted outrage in sections of Rhodesian Front's right wing, but he remained unassailable within the party as a whole, which had in late 1975 granted him a mandate to negotiate for the best possible settlement however he saw fit.[214] The split in the party ultimately led to the defection in July 1977 of 12 RF MPs after Smith introduced legislation to remove racial criteria from the Land Tenure Act.[215][n 31]

The loss of these seats to the breakaway Rhodesian Action Party, which opposed any conciliation with black nationalists, meant that Smith now only barely had the two-thirds majority in parliament he would need to change the constitution, as he would have to in the event of a settlement. He therefore called an early election, and on 31 August 1977 roundly defeated the defectors—"the dirty dozen", the RF called them—as well as all other opposition; for the third time in seven years, the RF had won all 50 white seats. The party revolt turned out to be a blessing in disguise for Smith, Berlyn comments, as it allowed him to "shed the dead wood of the right wing", giving him more freedom in negotiations with the nationalists.[215] The need for a settlement was becoming urgent—the war was escalating sharply, white emigration was climbing and the economy was starting to struggle as the UN sanctions finally began to have a serious effect.[215]

In March 1978, Smith and non-militant nationalist groups headed by Muzorewa, Sithole and Chief Jeremiah Chirau agreed what became the "Internal Settlement", under which the country would be reconstituted as Zimbabwe Rhodesia in June 1979 after multiracial elections. ZANU and ZAPU were invited to participate, but refused; Nkomo sardonically dubbed Smith's black colleagues "the blacksmiths".[216] The deal was badly received abroad, partly because it kept the police, the military, the judiciary and the civil service in white hands.[217] There would be a senate of 20 blacks and 10 whites, and whites would be reserved 28 out of 100 seats in the new House of Assembly.[n 32] Smith and Nkomo re-entered negotiations in August 1978, but these ended after ZIPRA shot down an Air Rhodesia passenger flight on 3 September and massacred survivors at the crash site.[218] Smith cut off talks, introduced martial law across most of the country and ordered reprisal attacks on guerrilla positions.[219] Smith, Muzorewa and Sithole toured the United States in October 1978 to promote their settlement,[220] and met Kissinger, Ford and others including the future president Ronald Reagan.[221] On 11 December, ZANLA attacked Salisbury's oil storage depot, causing a fire that lasted six days and destroyed a quarter of Rhodesia's fuel.[222] Two months later ZIPRA downed another civilian flight, this time killing all on board.[223]

After whites endorsed the Internal Settlement by 85% in a referendum on 30 January 1979,[224] Smith dissolved the Rhodesian parliament for the last time on 28 February.[225] The RF won all the white seats in the April 1979 elections while Muzorewa and the UANC won a majority in the common roll seats with 67% of the popular vote;[226] the PF rejected this, however, as did the UN, which passed a resolution branding it a "sham".[227] Sithole, astounded that his party had won only 12 seats to the UANC's 51, suddenly turned against the settlement and alleged that the polls had been stage-managed in Muzorewa's favour.[228] Mugabe dismissed the bishop as a "neocolonial puppet" and pledged to continue ZANLA's campaign "to the last man";[226] Nkomo similarly committed ZIPRA.[229] On 1 June 1979, the day of the country's official reconstitution as Zimbabwe Rhodesia, Muzorewa replaced Smith as prime minister, at the head of a UANC–RF coalition Cabinet made up of 12 blacks and five whites.[230] Smith was included as Minister without portfolio; Nkomo promptly dubbed him the "Minister with all the portfolios".[231]

An observer group from the UK Conservative Party did regard the April 1979 elections as fair,[231] and Margaret Thatcher, the Conservative leader, was personally disposed to recognise Muzorewa's government and lift sanctions. The potential significance of the Conservative victory in the May 1979 British general election was not lost on Smith, who wrote to Thatcher: "All Rhodesians thank God for your magnificent victory."[232] The United States Senate passed a resolution urging President Carter to remove sanctions and declare Zimbabwe Rhodesia legitimate,[233] but Carter and his Cabinet remained strongly opposed.[232] Carter and Thatcher ultimately decided against accepting Zimbabwe Rhodesia, noting the continued international support for the guerrillas.[234] After the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Lusaka in August 1979, the UK Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington invited the Zimbabwe Rhodesian government and the Patriotic Front to attend an all-party constitutional conference at Lancaster House in London, starting on 10 September.[235]

Smith was part of Muzorewa's delegation at Lancaster House. Several aspects of the Internal Settlement constitution, such as a declaration of human rights and a guarantee that land redistributed by the government would be paid for, were retained; it was also agreed to have 20 reserved white seats out of 100 for at least seven years. Fresh elections would be held during a brief period under a British governor invested with full executive and legislative powers. The new constitution was agreed on 18 October, and on 12 December 1979 the House of Assembly voted to dissolve itself, ending UDI. Lord Soames arrived in Salisbury later the same day to become Southern Rhodesia's last Governor; among other things he announced that Smith would be granted amnesty for declaring independence.[235] The final Lancaster House Agreement was signed on 21 December.[236] Smith was the only member of any delegation to openly oppose the accords; he refused to attend the signing ceremony and boycotted the post-agreement party, instead having dinner with former RAF comrades and Group Captain Sir Douglas Bader.[237]

The UK government and the international community ultimately declared the February 1980 general election free and fair,[238] though many observers attested to widespread political violence and intimidation of voters, particularly by ZANU (which added Patriotic Front to its name to become "ZANU–PF").[239] British monitors in the ZANU–PF-dominated eastern provinces were strongly critical, reporting "brutal 'disciplinary murders' as examples of the fate awaiting those who failed to conform", name-taking and "claims to the possession of machines which would reveal how individuals had voted".[240] The Commonwealth Observer Group acknowledged that irregularities were occurring but ruled that accounts were exaggerated.[240] After the RF won all 20 white seats, Soames announced late on 4 March 1980 that Mugabe and ZANU–PF had won 57 of the 80 common roll seats, giving them a majority in the new House of Assembly.[241]

Mugabe invited Smith to his house that evening and according to Smith treated him "most courteously"; Mugabe expressed joy at inheriting a "wonderful country" with modern infrastructure and a viable economy, outlined plans for gradual reform that Smith found reasonable, and said that he hoped to stay in regular contact. This meeting had a profound effect on the former prime minister.[242] Having denounced Mugabe as an "apostle of Satan" before the election, Smith now publicly endorsed him as "sober and responsible".[243] "If this were a true picture, then there could be hope instead of despair," he recalled in his autobiography. "When I got home I said to Janet that I hoped it was not an hallucination."[244]

Opposition

[edit]First years under Mugabe

[edit]

The new Zimbabwean parliament opened on 15 May 1980, a month after formal independence from Britain, with Smith as the reconstituted country's first Leader of the Opposition. Continuing a long-standing tradition from the Rhodesian era, the government and opposition entered the House in pairs—Mugabe and Smith walked in side by side with their respective MPs following, "aptly symbolis[ing] the mood of reconciliation", Martin Meredith comments.[245] With around 1,000 whites leaving Zimbabwe each month, Smith took to the radio to urge them to stay and give Mugabe's new order a chance,[246] but over half of the country's whites left within three years. As Meredith records, the 100,000 or so who remained "retreated into their own world of clubs, sporting activities, and comfortable living".[247] Mugabe made great efforts when he first took power to endear himself to the white farming community, which accounted for at least 75% of Zimbabwe's agricultural output.[248] Amid booming Zimbabwean commodity prices in the years immediately following 1980, many white commercial farmers came to support Mugabe.[249] The new prime minister continued cordially meeting Smith until the RF leader took him to task in 1981 for openly calling for a one-party state; Smith said this was putting off foreign investors.[247] Mugabe was not impressed and, according to Smith, refused to ever meet him again.[250]

As Mugabe's main opponent in Parliament at the head of the Republican Front (as the RF renamed itself in 1981), Smith presented himself as the guardian of what he called Zimbabwe's "white tribe". He spoke gloomily about Zimbabwe's future prospects, repeatedly accused the Mugabe administration of corruption, malevolence and general incompetence,[247] and criticised Mugabe's support for a one-party system.[251] The RF took an increasingly confrontational line in the House after Mugabe and other government ministers began regularly pouring scorn on the white community in national broadcasts and other media.[251] Amid rising tensions with South Africa, various white Zimbabweans were arrested, accused of being South African agents, and tortured. When Smith complained about whites being imprisoned without trial under emergency powers, a number of ZANU–PF MPs pointed out that they themselves had been detained under that same legislation, and for far longer, by Smith's government. Mugabe openly admitted torturing suspected spies, had some who were found not guilty by the High Court immediately rearrested on the street outside, and accused Western critics of caring only because the people in question were white.[252]

Smith visited Britain and the United States in November 1982, and spoke scathingly about Zimbabwe to reporters, claiming that Mugabe was turning the country into a totalitarian Marxist–Leninist dictatorship. Government retribution was immediate. On Smith's return home, police raided an art exhibition hosting him as guest of honour in Harare (as Salisbury had been renamed in April 1982) and took all the attendees in for questioning, ostensibly because of suspicions it might be an illegal political meeting. A week later, police seized his passport, according to a government statement because his criticism of Zimbabwe while abroad constituted "political bad manners and hooliganism".[253] Police meticulously searched his Harare house and Gwenoro over the next week, confiscating firearms, personal papers and a diary. Smith told reporters all this was "part of the game to intimidate me and so demoralise the whites".[253] Some RF MPs left the party to sit with ZANU–PF or as independents, feeling that constantly confronting Mugabe was ill-advised and unnecessary. Smith remained convinced that nobody would stand up for white Zimbabweans if they did not stick together and defend their interests in parliament.[253]

Smith Hempstone later wrote that the former prime minister had resolved to "go down ... with all rhetorical guns blazing".[254] This was in spite of increasingly unstable health; in June 1982 he collapsed in the House of Assembly, clutching at his side and shaking.[255] Half a year later he had to arrange treatment in South Africa for a condition stemming from hardening of the arteries. The government's confiscation of his passport and two refusals of its return prevented him from going, so in April 1983 Smith successfully applied for a British passport. "I'll still try to get my Zimbabwean passport back," he said. "I was born here and that is the passport I should travel on."[256] Smith regained his Zimbabwean papers after about a year.[257] In 1984, he declared his intention to renounce his British nationality to abide by a new Zimbabwean law outlawing multiple citizenship. Britain did not recognise this legislation; according to Smith, British officials refused to take his UK passport when he tried to return it.[257]

Gukurahundi; last years in politics