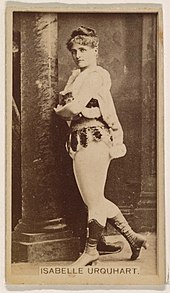

Isabelle Urquhart

Isabelle Urquhart (December 9, 1865 – February 7, 1907), also known as Belle Urquhart, was an American contralto and actress, noted for her performances in comic opera and musical comedy.

Born in New York City, Urquhart ran away from convent school to become a chorus girl. By 1881, she was performing chorus roles with the Richard D'Oyly Carte and E. E. Rice opera companies in America. She moved up to small roles with Augustin Daly's company from 1882 to 1883 and joined the H. M. Pitts comedy company for three London theatrical seasons, starting in 1883, while performing in New York City between those seasons.[a] By this time, she was playing principal roles in Victorian burlesque. In 1886, Urquhart played leading roles in Shakespeare and other dramas at the Globe Theatre in Boston, Massachusetts, but she reluctantly returned to comic opera in New York, where she played smaller roles that paid better.

Her first major role was Cerise in the hit musical Erminie, which ran from 1886 to 1888 at the Casino Theatre. She was noted for her impressive figure, and her fashion choices were admired by men and imitated by women. The Erminie role was followed by lead roles in other comic operas in New York City where she had become "one of the reigning queens of comic opera".[3] She appeared in vaudeville in the late 1890s. By 1900, she ran her own touring company and later took further roles in New York. By this decade, she was starring as older characters, earning strong notices. In 1906, she appeared in Broadway revivals of George Bernard Shaw's comedies Arms and the Man and How He Lied to Her Husband. The latter was her final role.

Urquhart was a popular model for cabinet cards that were distributed as a promotional incentive with cigarettes and other tobacco products. She was married to English actor Guy Standing from 1893 to 1899. She died of peritonitis in 1907 at the age of 41.

Early life

[edit]Urquhart was born in New York City on December 9, 1865, and was of Scottish ancestry.[3][4][5] Her father died when she was five years old.[5] At the age of ten, she enrolled in a convent school, where she sang in choirs.[6][7] When she was fifteen years old, Urquhart ran away from the convent school to seek a stage career, but her mother found her after two weeks and sent her back to the school.[6][8] She ran away again and found a job as a chorus girl, officially starting her theatrical career and ending her formal education.[8]

Career

[edit]Early career

[edit]

Urquhart's first theatrical job was as a chorus girl at the Standard Theatre in New York City for $10 a week ($339 in today's money).[8] She recalled that her first performance was in Gilbert and Sullivan's Patience.[8] Other sources say that her first stage appearance was in the chorus in Billee Taylor, produced by the Richard D'Oyly Carte and E. E. Rice opera companies on February 19, 1881.[5][9][10] She soon had a small role in a serio-comedic opera by Charles Brown called Elves and Mermaids.[11] She was in the chorus of another D'Oyly Carte production, the comic opera Claude Duval, the following theatrical season.[5][12]

Augustin Daly's company engaged Urquhart to play utility parts from 1882 to 1883.[4][13] In this capacity, she performed as Edinge in Giroutte, Mary Ann in The Passing Regiment, and in a production of Needles and Pins.[13][12] In The Squire, Urquhart played a 97-year-old woman, but not without some reservations; she recalled, "I was seventeen at the time, so I am not quite sure that I relished appearing as a nonagenarian."[6][12]

She spent three successful theatrical seasons in London, England, with the H. M. Pitts comedy company, starting in the summer of 1883.[4][8] Between these, in May 1884, she portrayed Cora Piper in Madame Piper at Wallack's Theatre on Broadway.[14][a] In September 1884, as a member of the Bijoux Theatre opera company, she played Venus in a burlesque, Orpheus and Eurydice, at Stetson's Fifth Avenue Theatre on Broadway.[15][6][16] She performed the role of Mars in another burlesque, Ixion in February 1885 at The New York Comedy Theatre.[17][18][b] During the 1885 to 1886 theater season in New York City, Urquhart was also in two comedies by George Bernard Shaw: Arms and the Man and How He Lied to Her Husband.[19]

In 1886, Urquhart acted in dramas with Lawrence Barrett at the Globe Theatre in Boston, Massachusetts, appearing as Portia in Julius Caesar, Nicol in The King's Pleasure, and Donna Isabella in The Wonder.[6][18] Her other drama roles included Gertrude in Hamlet and Hero in Much Ado About Nothing.[18] However, Rudolph Aronson persuaded her to return to comic opera because it paid better, though she stated in an interview, "I prefer legitimate drama to comic opera."[6][20]

Urquhart joined the Casino Theatre on Broadway, soon rising from the chorus to small parts in comic operas.[3] In the summer of 1885, she sang with Lillian Russell as Ensign Daffodil in Rice's production of Polly.[6][18] Her first major role was Cerise in the hit Erminie, which ran from May 1886 to October 1888 at the Casino.[3][21] As a leading lady in Erminie, she started a fashion trend by forgoing her petticoats "to accentuate her gorgeous figure".[22][13] Comedian and actor Francis Wilson recalled:

Over this innovation of Urquhart, men raved, and women, taking the hint, became imitators. Petticoats disappeared from female attire. In place of the bulging hourglass type of dress, adored by the Dutch, American women became an anatomy, a slender, clinging thing of beauty.... This startling change in female attire followed so pat upon the appearance and action of Miss Urquhart that I have ventured to credit her with its origin.[23]

Also at the Casino Theatre, Urquhart performed the role of Pompanoa in The Marquis in September 1887, and Princess Etelka in Nadja in May 1888.[24] She also played Dame Carruthers in Gilbert and Sullivan's The Yeomen of the Guard in October 1888 and was the Princess of Granada in the operetta The Brigands, W. S. Gilbert's translation of Offenbach's Les brigands, in May 1899.[9][25][26] In an 1889 revival of Nadja, Urquhart understudied Lillian Russell, filling in for the star as Princess Nadja on April 25 and 26.[27] In February 1890, she performed as Iza in The Grand Duchess of Gerolstein, with Russell in the title role.[28] While with the Casino company, Urquhart also played Papanea in Madelen.[6] In September 1891, Urquhart took on the role of Chloe in a Brooks and Dickson production of Sims and Clay's new operetta, The Merry Duchess, at the Standard Theatre in New York City.[29][30]

In 1893, Urquhart married English actor Guy Standing and announced her retirement from the stage in February.[31][32] However, later that year, Urquhart and Standing appeared together in a Loie Fuller production that closed after just two and a half weeks of its scheduled six-week run.[33] In October 1893, the couple sued Fuller for $1,000 for non-fulfillment of their contracts.[33]

Later career

[edit]When her marriage to Standing ended in divorce,[5][34] Urquhart returned to the stage and appeared in vaudeville in the late 1890s. In 1897, she performed a sketch of her own devising, at the Union Square Theatre, in which she "did little more ... than display her form in a handsome gown to the utmost advantage."[35] The same year, she performed in a show written for her, In Durance Vile, at B. F. Keith's vaudeville theater in Boston.[36] Although she had aged since her time with Casino Theatre company, one critic commented, "She has gained greatly in the quality of her acting, and her performance of the part in the little sketch in which she is making her continuous performance debut is entirely satisfactory to patrons of that form of amusement."[36]

In November 1900, her Isabelle Urquhart & Co. performed the comedy Even Steven again at B. F. Keith's; she also brought this vaudeville act to Procter's Theatres in September 1903, Keith's in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1903, and Shea's in Buffalo, New York, in 1904.[37][38][39][40] The Providence theater manager wrote in his report, "She never was very strong here, and this engagement is no exception. It is a nice clean act, and it is all right to play it about as often as we do. This is the first time we have had her in more than three years. She falls considerably short of being a headline feature."[39] The Shea's manager opined, "Miss Urquhart is a very good actress and has some fine gowns which show to advantage clothing her graceful figure."[40] In February 1900, Urquhart performed the lead role of Lady Garnett in Cecil Raleigh and Henry Hamilton's drama The Great Ruby at The Boston Theatre in Boston.[41] She then returned to Broadway, performing as Mrs. Challoner in Martha Morton's comedy The Diplomat at the Madison Square Theatre in April 1902.[5][42]

In 1906, she played the role of Mrs. Clandon in a production of George Bernard Shaw's You Never Can Tell in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[43] One critic wrote, "Urquhart played the advanced mother with grace and power."[43] She also performed in Broadway revivals of Shaw's comedies Arms and the Man, in April 1906, and How He Lied to Her Husband, in May 1906.[5][44] The latter was her final role.[45] In May 1914, Leander Richardson wrote in Vanity Fair that Urquhart's "figure was both imposing and beautiful – an Amazonian type; stately, superb ... Urquhart never rose very high in the profession, for her talents were not greatly out of the ordinary. But in a decorative capacity she was certainly second to none".[46]

Trade cards

[edit]Urquhart was a frequent model for cabinet cards that were distributed as a premium or gift with tobacco purchases.[47] She was featured on cabinet cards issued by Newsboy cigars and Falk Tobacco Company.[47][48][49] Around 1888, she posed for trade cards issued by Allen & Ginter for its Dixie, Opera Puff Cigarettes, Our Little Beauties, and Virginia Brights.[50] In 1889, she was included in the actresses trade card series issued by William S. Kimball & Co. to market its cigarettes.[51]

Also in the 1880s, Urquhart posed for a trade card for W. Duke, Sons & Company which marketed its Cameo Cigarettes.[52] Duke also included Urquhart in its promotional booklet, Costumes of All Nations.[53] Within two years, Duke was the largest cigarette manufacturer in the United States.[54] In 1890, Kinney Brothers Tobacco Company issued an Urquhart trade card to promote Sweet Caporal cigarettes.[55] Around the same time, Kinney Brothers issued a colorized trade card featuring Urquhart to promote its Sporting Extra cigarettes.[56]

Personal life

[edit]In 1890, Urquhart lived with her mother and aunt in a New York City apartment that overlooked the Metropolitan Opera House.[57]

She married English actor Guy Standing in London on January 30, 1893.[32][5] Standing was eight years younger than Urquhart and was the son of well-known actor Herbert Standing.[5][34] They divorced six years later.[5][34] In their divorce settlement, Urquhart received $10 a week in alimony from Standing; by February 1905, he was in arrears for $2,475 ($83,930 in today's money).[58] In 1906, she lived in New Rochelle, New York.[6]

Death

[edit]Urquhart was stricken with peritonitis on January 21, 1907.[5] After two operations, she died on February 7, 1907, at the Homeopathic Hospital in Rochester, New York, at the age of 41.[5] Her funeral was held at her home in New York City, The Shantee, and she was buried in the family plot at Woodlawn Cemetery.[45]

Gallery

[edit]- Urquhart, c. 1888 (Allen & Ginter trade card)

- Urquhart, c. 1888 (Costumes of All Nations, W. Duke, Sons & Co)

- Urquhart, c. 1888 (Virginia Brights trade card)

- Urquhart, c. 1888 (Virginia Brights trade card)

- Urquhart, c. 1890 (Sporting Extra Cigarettes trade card)

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Season Dates: The London Stage Calendar 1800-1844", London Stage Project, University of Oxford (2021)

- ^ Leach, Robert. An Illustrated History of British Theatre and Performance, Volume One, Chapter 39, p. 342, Routledge (2018) ISBN 9780815374824

- ^ a b c d "Isabelle Urquhart". The Opera Glass. 4 (8): 121. August 1897. Retrieved July 31, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Burroughs, Marie. "Isabelle Urquhart," in The Marie Burroughs Art Portfolio of Stage Celebrities: A Collection of Photographs of the Leaders of Dramatic and Lyric Art. Chicago: A.N. Marquis & Company, 1904. via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Isabelle Urquhart Dead" (PDF). The New York Times. February 8, 1907. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Browne, p. 218

- ^ Dale, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d e Urquhart, Isabelle. "Triumphs and Failures. Isabelle Urquhart Tells of a Stage Career", Temptations of the Stage, United States: J. S. Ogilvie, 1903. p. 77. via Google Books.

- ^ a b Stone, David. Belle Urquhart, Who Was Who in the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, August 27, 2001, accessed June 26, 2010

- ^ Dale, p. 121.

- ^ Dale, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b c Dale, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Londré, Felicia Hardison, and Fisher, James. Historical Dictionary of American Theater: Modernism. United States, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017. pp. 681–682.

- ^ Brown, pp. 315–316.

- ^ Brown, p. 43.

- ^ Dale, p. 123.

- ^ Brown, p. 212.

- ^ a b c d Dale, p. 124.

- ^ Browne, p. 219.

- ^ Dale, p. 125.

- ^ "Erminie". IBDB Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ "This is the Francis Wilson Playhouse: But Who Was Francis Wilson?" (PDF). Francis Wilson Playhouse. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 19, 2006. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ^ Wilson, Francis. Francis Wilson's Life of Himself. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1924. p. 86. via Google Books.

- ^ Brown, pp. 489–492.

- ^ Krehbiel, Henry Edward. Review of the New York Musical Season 1888-1890: Containing Programmes of Noteworthy Occurrences, with Numerous Criticisms. New York: Novello, Ewer & Company, 1889. pp. 2 and 156. via Google Books.

- ^ Brown, pp. 490–491.

- ^ Brown, p. 490.

- ^ Brown, p. 492.

- ^ Brown, p. 249.

- ^ "Amusements: The Merry Duchess" (PDF). The New York Times. September 8, 1883. p. 4. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ "A Clever Woman's Exploits: The Doings of Isabelle Urquhart Have the Charm of Novelty". The Kansas City Times. February 19, 1893. p. 17. Retrieved October 22, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Isabelle Urquhart Married". The Brooklyn Citizen. January 31, 1893. p. 3. Retrieved October 22, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Isabelle Urquhart Standing". Muncie Evening Press. Muncie, Indiana. October 10, 1893. p. 7. Retrieved October 22, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Browne, p. 211.

- ^ Erdman, Andrew L. (2004). Blue Vaudeville: Sex, Morals and the Mass Marketing of Amusement, 1895–1915. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland Co. p. 87. ISBN 0-7864-1827-3.

- ^ a b "Keith's Theatre". Boot and Shoe Recorder. 31 (14): 131. July 7, 1897 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Program at Keith's". Boston Home Journal. 56 (44): 13. November 3, 1900 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Music and Drama: Proctor's Theatres". The Tammany Time. 21 (20): 4. September 12, 1903 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Monod, David. "Isabelle Urquhart". Vaudeville America. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ a b Monod, David. "Isabelle Urquhart & Co". Vaudeville America. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ "The Great Ruby". The Play. 1 (10). February 12, 1900. Retrieved July 31, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Madison Sq. Theatre: The Diplomat". The Cast. 7 (9): 28. April 28, 1902 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "At the Theatres". The Index. 14 (12): 17. March 26, 1905 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Isabelle Urquhart". Internet Broadway Database. The Broadway League. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ a b "Funeral of Isabelle Urquhart" (PDF). The New York Times. February 11, 1907. p. 9. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ Richardson, Leander (July 1914). "The Chorus Girls of Yester-Year". Vanity Fair. p. 51 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "Isabelle Urquhart: Comic Opera and Musical Comedy Star (Photograph by Newsboy)". The Cabinet Card Gallery. March 26, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ "Isabelle Urquhart, 1890, Cabinet Photos # 1, 2, 3 Count | #403978026". Worthpoint. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ "Cabinet Cards - Falk, 1860 - 1900 | Rare and Distinctive Collections". University Libraries University of Colorado Boulder. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ "Belle Urquhart, from the Actors and Actresses series (N45, Type 1) for Virginia Brights Cigarettes". Met Museum. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ "Belle Urquhart, from the Actresses series (N203) issued by Wm. S. Kimball & Co". The Met Museum. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ "Card Number 108, Belle Urquhart, from the Actors and Actresses series (N145-4) issued by Duke Sons & Co. to promote Cameo Cigarettes". The Met Museum. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ Costumes of All Nations. Durham: W. Duke, Sons & Co. 1888. p. 16 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Darden, Robert F. (2006). "W. Duke, Sons and Company". NCpedia. Retrieved October 3, 2023.

- ^ "Isabelle Urquhart, from the Actresses series (N245) issued by Kinney Brothers to promote Sweet Caporal Cigarettes". The Met Museum. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ "Belle Urquhart, from the Actresses series (N246), Type 2, issued by Kinney Brothers to promote Sporting Extra Cigarettes". The Met Museum. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ Dale, p. 117.

- ^ "Guy Standing". Transcript-Telegram. Holyoke, Massachusetts. February 11, 1905. p. 6. Retrieved October 22, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

Sources

[edit]- Brown, Thomas Allston (1903). A History of the New York Stage: From the First Performance in 1732 to 1901. Vol. 3. New York: Dodd, Mead – via Google Books.

- Browne, Walter; Koch, E. De Roy, eds. (1906). "Urquhart, Isabelle". Who's Who on the Stage. New York: Walter Browne & F. A. Austin – via Google Books.

- Dale, Alan (1890). "Isabelle Urquhart". Familiar Chats with the Queens of the Stage. New York: G. W. Dillingham. Retrieved July 23, 2022 – via Google Books.

External links

[edit]- Photographs, New York Public Library

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch