Jacob Zuma corruption charges

This article needs to be updated. (June 2024) |

| ||

|---|---|---|

African National Congress uMkhonto weSizwe President (2009–2018)

Media gallery | ||

Jacob Zuma, the former president of South Africa, is currently facing criminal charges relating to alleged corruption in the 1999 Arms Deal. He was first indicted on the charges in June 2005, but attempts to prosecute him have been beset by legal challenges and political controversy. He is currently charged with two counts of corruption, one count each of racketeering and money laundering, and twelve counts of fraud, all arising from his receipt of 783 payments which the state alleges were bribes from businessman Schabir Shaik and French arms company Thales.[1][2]

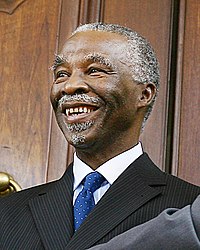

The Arms Deal, a major defence procurement package, was signed shortly after Zuma was appointed deputy president in 1999, and both Shaik and Thales had financial interests in the underlying contracts. By 2003, Zuma was one of several South African politicians rumoured to have benefited improperly from the deal, and these rumours appeared to receive substantiation during Shaik's criminal trial. In June 2005, the court convicted Shaik of making corrupt payments to Zuma in connection with the Arms Deal, including annual payments of R500,000 made on behalf of Thales. In the aftermath of the judgement, President Thabo Mbeki fired Zuma as deputy president, and the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) instituted formal corruption charges against him. However, the charges were struck off the court roll in September 2006 due to the NPA's unreadiness to proceed with the trial.

At the Polokwane conference in December 2007, Zuma was elected president of the African National Congress (ANC), the ruling party. Just over a week later, the NPA reinstated the charges against him. The charges were set aside again in September 2008, when high court judge Chris Nicholson declared them unlawful on procedural grounds. Nicholson also suggested that political interference in the NPA had played a significant role in Zuma's prosecution. This finding inflamed an ongoing political rivalry between Zuma and Mbeki, and it led the ANC National Executive Committee to demand Mbeki's resignation as national president. In January 2009, the Supreme Court of Appeal overturned Nicholson's ruling. Yet in April 2009, the NPA voluntarily withdrew the charges against Zuma due to new allegations of prosecutorial misconduct, this time fuelled by the so-called spy tapes.

Zuma's presidency lasted between May 2009 and February 2018. In the middle of his second term, in April 2016, the Pretoria High Court ruled that the NPA's April 2009 decision to drop the charges had been irrational. That decision was therefore set aside, and the NPA's new leadership was required to decide anew whether to reinstate the charges. On 16 March 2018, just over a month after Zuma resigned as president, the NPA announced that Zuma would again face prosecution. His first court appearance was on 6 April 2018 in the Durban Magistrates' Court, but the trial was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic and by what commentators dubbed Zuma's Stalingrad defence. In the interim, in a separate legal matter, he was imprisoned for contempt of court. He pleaded not guilty to the Arms Deal charges on 26 May 2021, and the trial was set to resume on 11 April 2022.[3]

Background

[edit]1999: The Arms Deal

[edit]The 1999 Arms Deal, a R30-billion defence procurement package, was signed by the South African governments months after Zuma's appointment to the deputy presidency in 1999. It was subject to numerous allegations of profiteering and corruption almost from the outset. In late 2002, the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) announced that Zuma was one of several African National Congress (ANC) politicians under investigation by the Scorpions for corruption related to the Arms Deal.[4] In August 2003, National Director of Public Prosecutions (NDPP) Bulelani Ngcuka told the media that the NPA had a "prima facie case of corruption" against Zuma but had decided not to prosecute on the basis that the case was probably not winnable.[4]

2004–2005: Shaik trial

[edit]

The next year, however, Zuma became a key figure in the 2004–2005 trial of Schabir Shaik, a Durban businessman and his friend and financial adviser. The trial concerned subcontracts for the four Valour-class frigates which had been procured for the South African Navy under the Arms Deal. Shaik had a close business relationship with Thomson-CSF (later Thales), which had won the contract to provide the combat suites for the frigates. A company which Shaik part-owned, Altech Defence Systems (later African Defence Systems), also won an Arms Deal subcontract, though only after it had been acquired by Thomson by 1999.[5][6]

On 2 June 2005, Shaik was sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment on two counts of corruption and one count of fraud.[7][8] The centre of the state's case was that there had been a "generalised pattern of corrupt behaviour" between him and Zuma.[1] (A version of this phrase is often mistakenly attributed to the presiding judge, rather than to its true source, the NPA.)[9] The fraud charge was for misrepresenting the financial records of one of his companies,[1] while both corruption charges related to undue payments which Shaik had made to Zuma. Between 1995 and 2002, Shaik paid Zuma a total of R1.28 million, either directly or through his companies, in the knowledge that Zuma would be unable to pay him back. The court found that this suggested that the payments had been made in anticipation of some business-related benefit that Zuma could deliver through his political office and connections.[1] Separately, beginning in the year 2000, Shaik also facilitated a pre-arranged annual payment of R500,000 from Thales to Zuma, made through Shaik's business accounts. The court concluded that the annual payments were intended to purchase Zuma's assistance in protecting Thales from investigation and in improving its profile for future government tenders.[1] This conclusion was supported by the infamous "encrypted fax."[10][11]

The judgement in the Shaik case, written by judge Hilary Squires, mentions Zuma by name 471 times.[12] Although it does not explicitly allege a corrupt relationship between Zuma and Shaik, it refers to the "mutually beneficial symbiosis" between them:

It would be flying in the face of commonsense and ordinary human nature to think that [Shaik] did not realise the advantages to him of continuing to enjoy Zuma's goodwill to an even greater extent than before 1997; and even if nothing was ever said between them to establish the mutually beneficial symbiosis that the evidence shows existed, the circumstances of the commencement and the sustained continuation thereafter of these payments, can only have generated a sense of obligation in the recipient [Zuma].[12]

2005–2006: First indictment

[edit]In the aftermath of the Shaik trial, President Thabo Mbeki fired Zuma from the deputy presidency, and on 20 June 2005 NDPP Vusi Pikoli announced that the NPA would prosecute him on corruption charges.[13] A provisional indictment was served on Zuma in November, mirroring the indictment earlier served on Shaik, and arms company Thint (a local subsidiary of Thales) was charged as his co-accused.[14] However, in July 2006, the NPA applied for a postponement, pending the finalisation of the indictment. The indictment was apparently obstructed by delays in securing evidence and in pending appeals by Shaik, Zuma, and Thint.[14] Shaik was appealing his conviction, while Zuma and Thint were challenging the legality of a series of search-and-seizure raids, carried out by the Scorpions in August 2005, on various premises including homes and offices of Zuma, his lawyers, Shaik, and Thint director Pierre Moynot.[15]

September 2006: Charges struck off

[edit]Zuma and Thint opposed the state's application for postponement and applied for a permanent stay of prosecution, which would have seen the charges permanently invalidated.[14] On 20 September 2006, the Pietermaritzburg High Court dismissed the state's application for a postponement and, when the NPA indicated that it was not prepared to proceed with the trial, struck the matter off the roll.[16] This rendered moot the application for a permanent stay. The presiding judge said that, given the NPA's lack of a final indictment, the prosecution had been "anchored on unsound foundations" from the start.[16] However, the NPA indicated that it would consider reinstating the charges,[16] and on 8 November 2007 the Supreme Court of Appeal ruled in the NPA's favour in confirming the legality of the August 2005 raids, thus opening the possibility that the evidence seized could be used to prosecute Zuma and Thint in the future.[14][17]

2007–2009: Second indictment

[edit]

On 28 December 2007, just over a week after the ANC National Conference at which Zuma had been elected ANC president, acting NDPP Mokotedi Mpshe announced that the charges against Zuma and Thint had been reinstated, and Zuma was served with another indictment.[17] He faced twelve fraud charges, two corruption charges, and one charge each of racketeering and money laundering.[18] A conviction and sentence to a term of imprisonment of more than one year would have rendered Zuma ineligible for election to Parliament, and consequently he would not have been eligible to serve as president of South Africa following the 2009 elections, in which he was expected to stand as the ANC's candidate.[19]

September 2008: Charges declared unlawful

[edit]Zuma revived the challenge against the legality of the 2005 raids, but the appeal was conclusively rejected by the Constitutional Court in July 2008 in Thint v NDPP.[14] In the interim, however, Zuma had applied to have the charges against him, due to be heard in court from 4 August, declared invalid and unconstitutional.[14] On 12 September 2008, Pietermaritzburg High Court judge Chris Nicholson ruled in his favour, setting the charges aside as unlawful on the grounds that the NPA had not given Zuma a chance to make representations before deciding to charge him. According to Nicholson, the audi alteram partem principle and Section 179(5)(d) of the Constitution required that such an opportunity be extended to Zuma. The state was directed to pay Zuma's legal costs.[20][21][22] Nicholson stressed that Zuma's guilt or innocence was irrelevant to his ruling, which turned on a merely procedural point.[21]

However, Nicholson also commented on the impartiality of the NPA, saying that he believed that political interference had played a significant role in the decision to reinstate Zuma. Zuma's supporters – including prominent figures such as lawyer Paul Ngobeni[23] – had previously alleged that the charges were the result of a political conspiracy by Zuma's political rival, President Mbeki. Nicholson appeared to concur, saying that he was "not convinced that the applicant was incorrect when he averred political meddling in his prosecution" and that the case seemed to be part of "some great political contest or game."[20][22] In paragraphs 210 and 220, the judgement reads:

The timing of the indictment by Mr Mpshe on 28 December 2007, after the President suffered a political defeat at Polokwane was most unfortunate. This factor, together with the suspension of Mr Pikoli, who was supposed to be independent and immune from executive interference, persuade me that the most plausible inference is that the baleful political influence was continuing. [...] There is a distressing pattern in the behaviour which I have set out above indicative of political interference, pressure or influence. It commences with the 'political leadership' given by [Justice] Minister [Penuell] Maduna to Mr Ngcuka, when he declined to prosecute the applicant, to his communications and meetings with Thint representatives and the other matters to which I have alluded. Given the rules of evidence the court is forced to accept the inference which is the least favourable to the party's cause who had peculiar knowledge of the true facts... It is a matter of grave concern that this process has taken place in the new South Africa given the ravages it caused under the Apartheid order.[24]

January 2009: Charges reinstated on appeal

[edit]Both the NPA and Mbeki applied to appeal Nicholson's ruling.[17] Mbeki, whom the ANC National Executive had asked to resign as a direct result of the ruling, said in an affidavit:

It was improper for the court to make such far-reaching 'vexatious, scandalous and prejudicial' findings concerning me, to be judged and condemned on the basis of the findings in the Zuma matter. The interests of justice, in my respectful submission would demand that the matter be rectified. These adverse findings have led to my being recalled by my political party, the ANC – a request I have acceded to as a committed and loyal member of the ANC for the past 52 years. I fear that if not rectified, I might suffer further prejudice.[25]

The Supreme Court of Appeal heard the NPA's application from November 2008, and on 12 January 2009 Deputy Judge President Louis Harms ruled in the NPA's favour, overturning Nicholson's ruling.[26][27] On the central question of whether the charges against Zuma had been unlawful, the court found that Nicholson had misapplied Section 179 of the Constitution: the NPA had not been obliged to invite representations from Zuma before reinstating the charges against him. On the further challenge to Nicholson's allegations of political interference, the court found that such allegations were not properly relevant to Nicholson's decision, had not been demonstrated in the evidence, and reflected the fact that the lower court had "overstepped the limits of its authority."[26] Harms said that findings about political meddling by Mbeki and others appeared to have derived from Nicholson's "own conspiracy theory,"[27] and that:

Political meddling was not an issue that had to be determined. Nevertheless a substantial part of [Nicholson's] judgement dealt with this question. He changed the rules of the game, he took his eyes off the ball.[26]

In a statement, the ANC responded to the ruling by reiterating its support for Zuma as its presidential candidate in the 2009 elections.[26]

April 2009: Charges withdrawn

[edit]In subsequent months, although the Supreme Court of Appeal's judgement cleared the way for Zuma's trial to continue, new allegations of prosecutorial misconduct emerged. These allegations revolved around the so-called spy tapes: recordings of intercepted phone calls which Zuma's lawyers claimed showed that the head of the Scorpions, Leonard McCarthy, had conspired with Ngcuka, the former NDPP, over the timing of the charges laid against Zuma, in service of Mbeki's political advantage.[28] On 6 April 2009, Mpshe, still the acting NDPP, announced that all charges against Zuma (and against Thint) would be dropped, prosecution being "neither possible nor desirable."[17][29] He stressed that the decision was due to abuses which had "tainted" the legal process, and that it did not amount to a substantive acquittal.[30] The charges against Zuma were formally withdrawn in the same week that he was inaugurated as national president.[17]

2018–present: Third indictment

[edit]April 2016: Withdrawal of charges overturned

[edit]Shortly before the NPA its decision in April 2009, at least two political parties had intimated that they would consider legal action of their own should the charges be dropped.[31] The Democratic Alliance (DA) subsequently filed an application for a judicial review of the NPA's decision, with party leader Helen Zille claiming that Mpshe had "not taken a decision based in law, but [instead had] buckled to political pressure."[32] The case was set to be heard on 9 June 2009.[33] However, following initial delays by the NPA[34] and legal challenges to the application by both Mpshe and Zuma,[35] judgement was not laid down until April 2016, when Zuma was well into his second term as president.

On 29 April 2016, the Pretoria High Court ruled that the NPA's decision in 2009 to drop the charges against Zuma had been irrational. Judge Aubrey Ledwaba said that Mpshe had acted "alone and impulsively" in deciding to drop the charges, when he should properly have followed legal processes and approached the courts in regard to the spy tapes allegations.[35] The decision to withdraw the charges was therefore set aside, and the NPA, under the new NDPP Shaun Abrahams, had to decide anew whether it would reinstate the charges.[35]

Zuma and the NPA unsuccessfully challenged the high court's ruling in the Supreme Court of Appeal, which dismissed their application with costs on 13 October 2017.[36][37] Zuma was given a 30 November deadline to present reasons to the NPA as to why his prosecution should not proceed.[37][38]

March 2018: Charges reinstated

[edit]On 16 March 2018, just over a month after Zuma resigned from the presidency, Abrahams announced that Zuma would again face prosecution on 16 criminal charges – 12 charges of fraud, two of corruption, and one each of racketeering and money laundering, just as in the 2006 indictment.[39] His first court appearance was on 6 April in the Durban Magistrates' Court.[40] The trial began on 26 May 2021 in the Pietermaritzburg High Court, and he has pleaded not guilty.[22][41] However, between 2018 and the present, Zuma has launched a series of pre-trial court applications which some have dubbed his Stalingrad defence.[42][43]

Application for stay of prosecution

[edit]On 11 October 2019, the KwaZulu-Natal High Court dismissed Zuma's application for a permanent stay of prosecution,[44] pointing out that it relied on several arguments that had already been rejected by other courts presiding over earlier applications in the case.[42] Thales lost on a similar application,[44] and, on 22 January 2020, also failed to have racketeering charges against it struck down.[45][46] Both the high court and the appellate court denied Zuma leave to appeal the ruling on the stay of prosecution.[47]

Warrant of arrest

[edit]A warrant was issued for Zuma's arrest after he failed to appear in court in February 2020. His legal team claimed that he was in Cuba receiving medical treatment.[48][49] The warrant was suspended until May, at which point, due to COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, it was stayed until June,[50] when it was cancelled because Zuma had produced a medical certificate verifying his illness.[51]

State liability for legal costs

[edit]A separate series of applications concerned the payment of Zuma's legal fees. In 2006, following the first indictment, President Mbeki had signed an agreement stipulating that the state would pay Zuma's legal fees. In December 2018, the Pretoria High Court overturned the agreement, finding that "the state is not liable for the legal costs incurred by him in his personal capacity."[52] Zuma unsuccessfully appealed the ruling in the Supreme Court of Appeal, opposed by both the DA and the Economic Freedom Fighters. The court found on 13 April 2021 that the state was not responsible for financing his legal defence, that he should repay funds to the state, and that he should incur punitive costs for having accused the judges of bias.[52] The state's contribution to Zuma's legal fees has been estimated at between R16.78 million[52] and R32 million.[43][53]

Application for the removal of Billy Downer

[edit]In May 2021, shortly before the long-delayed corruption trial was due to start, Zuma applied for the removal of prosecutor Billy Downer from the proceedings.[54][22] He filed a special plea in terms of Section 106 of the Criminal Procedure Act, asking for Downer's removal from the case and for his own immediate acquittal if the plea was accepted.[55] Among other things, Zuma claimed that Downer lacked the proper authority to try the case, but the NPA said that Downer has been working on the Arms Deal case for close to 20 years and is duly mandated to prosecute it.[54] Downer also denied Zuma's allegations that he is not impartial and is personally obsessed with prosecuting Zuma.[47]

On 26 October 2021, the court dismissed the application.[3][56] Zuma is currently seeking leave to appeal the decision in the Supreme Court of Appeal, but the NPA has opposed the application, claiming that it is one of many applications brought by Zuma "which have had the effect of obstructing and delaying the start of the criminal trial on the merits of the criminal charges against him." High court judge Piet Koen is expected to deliver judgement on that application on 16 February.[55] Zuma also laid criminal charges against Downer in October 2021, claiming that Downer had leaked confidential information about the case to the media.[57] Barring an appeal, the corruption trial was set to resume on 11 April 2022.[3]

Judge recuses himself from the trial

[edit]On 13 August 2024, Piet Koen, the trial judge, recused himself from the case. In January 2024, Judge Koen had announced, "I have come to the conclusion that I must recuse myself from the trial."[58]

When a judge recuses themselves from a trial, a new judge takes over, meaning the trial will start over.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Open Secrets (5 May 2020). "Jacob Zuma – Comrade in Arms". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Erasmus, Des (31 January 2022). "Zuma's fight to remove prosecutor Billy Downer from Arms Deal trial continues". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ a b c AfricaNews (26 October 2021). "Zuma loses plea to remove prosecutor, corruption trial to start in April". Africanews. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b Bruce, David (2008). "Without fear or favour: The Scorpions and the politics of justice". SA Crime Quarterly. 24.

- ^ Report of the joint investigation into the Strategic Defence Procurement Packages (PDF). Pretoria: Government Printer. 14 November 2001.

- ^ "I had no conflict of interest: Chippy Shaik". Sunday Times. 11 November 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Peta, Basildon (8 June 2005). "Corruption sentence seals fate of Mbeki deputy". The Independent. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ "Shaik sentenced to 15 years in prison". SABC News. 6 August 2005. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- ^ Berger, Guy (22 November 2006). "Suckers for the sound bite". Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ^ "Encrypted Fax". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ "Zuma: Author of encrypted fax could testify". IOL. 23 August 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Full transcript of Shaik judgment". News24. 9 June 2005. Archived from the original on 22 March 2009.

- ^ "Zuma avoids 'physical arrest'". IOL. 20 June 2005. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Oellermann, Ingrid (4 August 2008). "Zuma's long path to court". IOL. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018.

- ^ "Zuma feels the sting of the Scorpions". IOL. 18 August 2005. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b c "Zuma corruption trial struck off the roll". SABC News. 20 September 2006. Archived from the original on 26 October 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ^ a b c d e "A timeline of Jacob Zuma's presidency". Independent Online. 15 February 2018. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018.

- ^ "'Zuma application shouldn't be taken lightly'". IOL. 12 September 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Constitution of the Republic of South Africa". Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ a b Zigomo, Muchena (11 September 2008). "South African judge throws out Zuma graft case". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ a b "SA court rejects Zuma graft case". BBC News. 12 September 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d Orr, James (12 September 2008). "South African court clears way for Zuma presidential run". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ Ngobeni, Paul. "State Versus Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma: A Litigation Cookbook" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2011.

- ^ "Full Zuma judgment". News24. 13 September 2008. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008.

- ^ Lourens, Carli (23 September 2008). "South Africa's Mbeki Plans to Challenge 'Improper' Court Ruling". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d John, Mark; Kulikov, Yuri (12 January 2009). "Court upholds NDPP appeal in Zuma case". Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017.

- ^ a b Maughan, Karyn (12 January 2009). "SCA opens the door for new Zuma charges". IOL. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Mpshe reveals contents of Ngcuka, McCarthy tapes". Mail & Guardian. 6 April 2009. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ Gordin, Jeremy (8 April 2009). "Jacob Zuma: Jeremy Gordin analysis". Dispatch Now 24/7. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009.

- ^ "Mpshe: Zuma decision not an acquittal". Mail & Guardian. 6 April 2009. Archived from the original on 9 April 2009.

- ^ Du Plessis, Carien (2 April 2009). "Is NPA entitled to drop Zuma charges?". Cape Times. Archived from the original on 6 April 2009.

- ^ Mboyisa, Cedric (6 April 2009). "DA files for judicial review". Citizen. Archived from the original on 8 April 2009.

- ^ Joubert, Pearlie; Basson, Adriaan (9 April 2009). "The Spy Who Saved Zuma". Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009.

- ^ "Mpshe showing contempt for law: Zille". Independent Online. South Africa. 30 September 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- ^ a b c Herman, Paul (29 April 2016). "Decision to drop Zuma corruption charges 'irrational', set aside". News24. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ Ndaba, Baldwin (15 September 2017). "Pressure mounts on Zuma to step down after 'irrational' admission". IOL. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b Bateman, Barry (13 October 2017). "SCA upholds High Court decision on Zuma charges". EWN. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017.

- ^ "NPA gives Zuma November deadline to say why he shouldn't be prosecuted". Sunday Times. 20 October 2017. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ "Jacob Zuma: Former South African president faces corruption trial". BBC News. 16 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Cotterill, Joseph (6 April 2018). "Jacob Zuma makes first court appearance in arms graft case". Financial Times. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Burke, Jason (26 May 2021). "Jacob Zuma trial: South Africa's ex-president denies corruption charges". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ a b Vos, Pierre de (27 October 2021). "Stalingrad defence: Zuma's costly and legally untenable attempts to avoid facing criminal charges". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b Corcoran, Bill (23 May 2019). "Zuma employing 'Stalingrad defence' as legal stalling strategy". The Irish Times. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b Burke, Jason (11 October 2019). "Zuma to stand trial on corruption charges relating to $2.5bn arms deal". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Mtshal, Samkelo (22 January 2021). "Green light for Zuma arms deal corruption trial after Thales loses court bid". Independent Online. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Maughan, Karyn (22 January 2021). "NPA's victory against Thales takes it one step closer to putting former president Zuma on trial". News24. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ a b Ferreira, Emsie (2 June 2021). "NPA accuses Zuma of another stab at stay of prosecution in a different guise". The Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "South African Court Issues Warrant for Jacob Zuma's Arrest". The New York Times. 4 February 2020. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Anna, Cara; Magome, Mogomotsi (4 February 2020). "South African court issues arrest warrant for ex-leader Zuma". ABC News. Associated Press.

- ^ Marriah-Maharaj, Jolene (6 May 2020). "Warrant of arrest for former President Jacob Zuma to be stayed until next court appearance". IOL. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Court cancels Zuma's warrant of arrest". eNCA. 23 June 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b c O'Regan, Victoria (13 April 2021). "The big buck stops with Jacob Zuma as court rules state will not pay legal fees for graft case". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Erasmus, Des (22 May 2021). "Millions, billions, gazillions: How much did we waste on Zuma's legal fees while our country was burning?". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b Ferreira, Emsie (20 May 2021). "NPA says Zuma is trying for another delay in arms deal trial". The Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b Erasmus, Des (30 January 2022). "Jacob Zuma in final push to avoid Arms Deal charges". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ Maughan, Karyn (27 October 2021). "How Judge Piet Koen's ruling puts Jacob Zuma in a very tight corner". News24. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Erasmus, Des (21 October 2021). "Ready to rumble: Zuma ups the ante and files criminal charges against prosecutor Billy Downer". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "South African judge on Zuma's corruption case recuses himself". Africanews. 30 January 2023. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch