Judenfrei

| Part of a series on |

| The Holocaust |

|---|

|

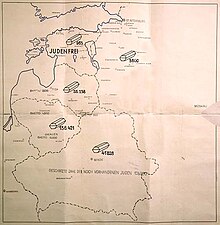

Judenfrei (German: [ˈjuːdn̩ˌfʁaɪ], "free of Jews") and judenrein (German: [ˈjuːdn̩ˌʁaɪn], "clean of Jews") are terms of Nazi origin to designate an area that has been "cleansed" of Jews during The Holocaust.[1] While judenfrei refers merely to "freeing" an area of all of its Jewish inhabitants, the term judenrein (literally "clean of Jews") has the even stronger connotation that any trace of Jewish blood had been removed as an alleged impurity in the minds of the criminal perpetrators.[2] These terms of racial discrimination and racial abuse are intrinsic to Nazi anti-Semitism and were used by the Nazis in Germany before World War II and in occupied countries such as Poland in 1939. Judenfrei describes the local Jewish population having been removed from a town, region, or country by forced evacuation during the Holocaust, though many Jews were hidden by local people. Removal methods included forced re-housing in Nazi ghettos especially in eastern Europe, and forced removal or Resettlement to the East by German troops, often to their deaths. Most Jews were identified from late 1941 by the yellow badge as a result of pressure from Joseph Goebbels and Heinrich Himmler.

Following the defeat of Germany in 1945, some attempts have been made to attract Jewish people back to Germany, as well as reconstruct synagogues destroyed during and after Kristallnacht. The terms judenrein and judenfrei have since been used in the persecution of global Jewish communities or Israel.[citation needed]

Locations declared judenfrei

[edit]Establishments, villages, cities, and regions were declared judenfrei or judenrein after they were apparently cleared of Jews. However, some Jewish people survived by being hidden and sheltered by friendly neighbours. In Berlin, they were known as "submariners" since they seemed to have disappeared (under the waves). Many survived the end of the war, hence becoming Holocaust survivors.

- Gelnhausen, Germany and Calw, Germany – reported judenfrei on November 1, 1938, by propaganda newspaper Kinzigwacht after their synagogues were closed and remaining local Jews forced to leave the towns.[3]

- German-occupied Bydgoszcz (Poland) – reported judenfrei in December 1939.[citation needed]

- German-annexed Alsace – reported judenrein by Robert Heinrich Wagner in July 1940.[4]

- Banat, German-occupied territory of Serbia – reported judenfrei on 19 August 1941 in Völkische Beobachter (lit. People's Observer).[5] On 20 August 1941 Banat was declared judenfrei by its German administrators.[6]

- German-occupied Luxembourg – reported judenfrei by the press on October 17, 1941.[7]

- German-occupied Estonia – December 1941.[8] Reported as judenfrei at the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942.[9]

- Independent State of Croatia – Declared judenfrei by Interior Minister Andrija Artuković in February 1942 but Germany suspected that this was not true and the authorities from Berlin sent Franz Abromeit to assess the situation. After that, the Ustaše were under pressure to finish the job. In April 1942 two hundred Jews from Osijek were deported to Jasenovac, while 2,800 were sent to Auschwitz.[10] The Gestapo organized the deportation to Auschwitz of the last Croatian Jews in May 1943, 1,700 from Zagreb and 2,500 from other parts of the NDH.[11][12]: 107 German diplomat Siegfried Kasche pronounced Croatia judenfrei in a message to Berlin on 18 April 1944, stating that "Croatia is one of the countries in which the Jewish problem has been solved".[13][14]

- German-occupied territory of Serbia / Belgrade – May 1942, reported in the SS-Standartenführer Emanuel Schäfer cable sent to the Reich Security Main Office in Berlin; Schäfer was the Der Befehlshaber der SIPO und des SD head at that time in Belgrade,[15][16][17][18] while in June 1942 he reported to his supervisors that "Serbien ist Judenfrei" (lit. "Serbia is free of Jews").[12]: 3 In August 1942, Harald Turner reported to the German commander in the Balkans that Serbia was the first European territory where the "Jewish problem" was solved.[19][20]: 118

- Vienna – reported judenfrei by Alois Brunner on October 9, 1942.

- Berlin, Germany – May 19, 1943.[21]

- Erlangen, Germany was declared judenfrei in 1944.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Scheffler, Wolfgang (2007). "Judenrein". Encyclopaedia Judaica (2 ed.). Thomson Gale.

- ^ "Aryanization: Judenrein & Judenfrei". shoaheducation.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2017. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ "'Gelnhausen endlich judenfrei': Zur Geschichte der Juden während der Nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung" ['Gelnhausen finally free of Jews': On the History of the Jews during the Nazi persecution] (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007.

- ^ Blumenkranz, Bernhard; Catane, Moshe (2007). "Alsace". Encyclopaedia Judaica (2 ed.). Thomson Gale.

- ^ Drndić, Daša (2009). April u Berlinu. Fraktura. p. 24. ISBN 978-953-266-095-1.

Njemački list Völkische Beobachter objavio je 19. kolovoza 1941. da je Banat konačno Juden frei.

- ^ Muth, Thorsten (2009). Das Judentum: Geschichte und Kultur. Pressel. p. 452. ISBN 978-3-937950-28-0.

Am 20. August konnte die deutsche Führung das Banat für Judenfrei" erklären.

- ^ "Commémoration de la Shoah au Luxembourg" [Commemoration of the Shoah in Luxembourg] (in French). Government of Luxembourg. July 3, 2005. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ^ "Extract from Report by Einsatzgruppe A". Archived from the original on November 12, 2007. Partial Translation of Document 2273-PS Source: Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Vol. IV. USGPO, Washington, 1946, pp. 944–949

- ^ "Estonian Jews". Simon Wiesenthal Center. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. sourced to Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. 1990.

- ^ Subotić, Jelena (2019). Yellow Star, Red Star: Holocaust Remembrance after Communism. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-50174-241-5.

- ^ Bulajić, Milan (2002). Jasenovac: the Jewish Serbian holocaust (the role of the Vatican) in Nazi-Ustasha Croatia (1941-1945). Fund for Genocide Research. p. 222. ISBN 9788641902211.

- ^ a b Subotić, Jelena (2019). Yellow Star, Red Star: Holocaust Remembrance after Communism. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501742415.

- ^ Jewish History of Yugoslavia, porges.net; accessed 5 May 2016.

- ^ "Povijest Židova Jugoslavije" (in French). Porges.net. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ Lituchy, Barry M. (2006). Jasenovac and the Holocaust in Yugoslavia: analyses and survivor testimonies. Jasenovac Research Institute. pp. xxxiii. ISBN 978-0-97534-320-3.

- ^ Manoschek, Walter (1995). "Serbien ist judenfrei": militärische Besatzungspolitik und Judenvernichtung in Serbien 1941/42. Walter de Gruyter. p. 184. ISBN 9783486561371.

- ^ Lebel, G'eni (2007). Until "the Final Solution": The Jews in Belgrade 1521 - 1942. Avotaynu. p. 329. ISBN 9781886223332.

- ^ Herbert, Ulrich; Schildt, Axel (1998). Kriegsende in Europa. Klartext. p. 149. ISBN 9783884745113.

- ^ John K. Cox; (2002) The History of Serbia p. 92-93; Greenwood, ISBN 0313312907

- ^ Prusin, Alexander (2017). Serbia Under the Swastika: A World War II Occupation. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09961-8.

- ^ "Was war am 19. Mai 1943" [What was on May 19, 1943] (in German). chroniknet. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch