John Newham

John William "Jake" Newham | |

|---|---|

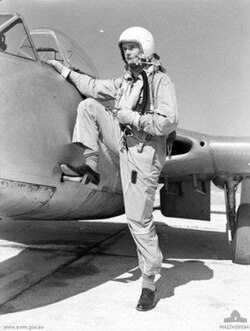

Pilot Officer Newham boarding a Vampire jet in Malta, 1953 | |

| Born | 30 November 1930 Cowra, New South Wales, Australia |

| Died | 27 December 2022 (aged 92) |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service | Royal Australian Air Force |

| Years of service | 1951–1987 |

| Rank | Air Marshal |

| Unit |

|

| Commands |

|

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | Companion of the Order of Australia Air Medal (US) |

| Other work | Company director |

Air Marshal John William "Jake" Newham, AC (30 November 1930 – 27 December 2022) was a senior commander of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). He served as Chief of the Air Staff (CAS) from 1985 until 1987. Joining the RAAF in 1951, he flew Gloster Meteor jets with No. 77 Squadron in the Korean War in 1953, and subsequently de Havilland Vampires with No. 78 Wing on garrison duty in Malta. From 1958 to 1960, he served with No. 3 Squadron, operating CAC Sabres during the Malayan Emergency. He took charge of No. 3 Squadron in 1967, when it re-equipped with the Dassault Mirage III supersonic fighter. His commands in the early 1970s included the Aircraft Research and Development Unit, RAAF Base Laverton, and No. 82 Wing, the last-mentioned during its first years operating the long-delayed General Dynamics F-111C swing-wing bomber. He was appointed Deputy Chief of the Air Staff in March 1984, and CAS in May the following year. His tenure as CAS coincided with the release of the Dibb Report on Australia's defence capabilities, and the controversial transfer of the RAAF's battlefield helicopters to the Australian Army. Newham retired from the Air Force in July 1987 and became a company director.

Early career

[edit]John William Newham, known as "Jake", was born in Cowra, New South Wales, and educated at Cowra High School. After matriculating, he worked as a clerk in the Commonwealth Bank, and joined the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) in February 1951.[1] He underwent flying training at RAAF Base Point Cook, Victoria, and graduated as a sergeant pilot in July 1952.[1][2] Following fighter training, he saw operational service in the Korean War, flying Gloster Meteor jets with No. 77 Squadron from February to September 1953.[3][4] He later recalled that his first sortie was as wingman to a Royal Air Force flight lieutenant: "We flew up past P'yongyang and he showed me enemy gun locations by arranging for them to shoot at us".[5]

Having been commissioned as a pilot officer midway through his Korean service, Newham's next posting was with No. 78 (Fighter) Wing on Malta, where he flew de Havilland Vampires until 1955.[1][2] The wing had been on garrison duty in Malta since July 1952, and Newham was one of five Korean War veterans who replaced pilots posted back to Australia.[6] He married Jo Cranston in 1956; the couple had two daughters and a son.[3] By November 1957, Newham had been promoted to flight lieutenant and was undergoing conversion training on the CAC Sabre. From 1958 to 1960 he served in Malaya with No. 3 Squadron, whose Sabres conducted operations against communist guerrillas in the final years of the Malayan Emergency.[3][7]

Rise to senior command

[edit]

Newham attended RAAF Staff College, Canberra, from January to December 1964.[8] He then served as Chief Flying Instructor at No. 2 Operational Conversion Unit at RAAF Base Williamtown, New South Wales, taking temporary command of the unit as a squadron leader from July 1965 to April 1966.[3][9] That August, he commenced conversion training on the Dassault Mirage III supersonic jet fighter.[10] Promoted to wing commander, from July 1967 to October 1968 he led No. 3 Squadron at Williamtown as it re-equipped with the Mirage.[1][11] In 1971, Newham was appointed commanding officer of the Aircraft Research and Development Unit. The following year he became Officer Commanding RAAF Base Laverton, Victoria.[2]

By now a group captain, Newham was appointed Officer Commanding No. 82 Wing at RAAF Base Amberley, Queensland, in 1973.[1][2] He formed the RAAF Washington Flying Unit at McClellan Air Force Base, California, on 31 March to ferry the first twelve (out of a total order of twenty-four) General Dynamics F-111C swing-wing bombers to Australia.[12] On 1 June, Newham led the first three F-111s in to land at Amberley, a gala occasion attended by the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence, Lance Barnard, the Chief of the Air Staff, Air Marshal Charles Read, the Air Officer Commanding Operational Command, Air Vice Marshal Brian Eaton, and a large media contingent. Newham later recalled that "our air force cred went up in the area and in the world with that aeroplane".[13] Read ordered Newham to operate the F-111 with great caution initially, well within limits, lest the long-delayed and controversial aircraft suffer greater damage to its reputation through early attrition. Despite Newham's protests over the plane's capabilities, the restrictions remained in place until 1975.[14] That year he was appointed Staff Officer Operations at Headquarters Operational Command (OPCOM).[2]

Senior command and later life

[edit]Newham was promoted air commodore in 1976 and became Senior Air Staff Officer at OPCOM, serving through the following year.[1][2] In 1978 he attended the Royal College of Defence Studies, London, and was made Director General of Operational Requirements in 1979.[2] In this capacity he visited Israel to investigate air-to-air refuelling operations, coming away favourably impressed: "the Israelis had more match practice than anybody around at the time. The experience gave me confidence in operational judgments."[15] He was promoted air vice marshal and appointed Chief of Air Force Operations in March 1980, effective from April, and served on the Chief of the Air Staff Advisory Committee.[16][17] In 1982 he was posted to the United States as the Head of Australian Defence Staff in Washington, D.C. Returning to Australia, Newham became Deputy Chief of the Air Staff in March 1984.[1][18] He was appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia on 11 June for services to the RAAF.[19]

Promoted to air marshal, Newham became Chief of the Air Staff (CAS) on 21 May 1985, succeeding Air Marshal David Evans.[20][21] Newham initially endorsed the Federal government's 1986 Review of Australia's Defence Capabilities, otherwise known as the Dibb Report, but shortly afterwards publicly criticised its "understanding of the application of air power" and "debatable judgments", especially its lukewarm attitude to the employment of the F-111s for strategic strike.[22] At a conference the same year, he reiterated the RAAF's position that "defensive action may prevent defeat, but wars can be won only by offensive action".[23] On 9 June, he was raised to Companion of the Order of Australia for service to the RAAF, "particularly as Chief of the Air Staff".[24] Newham's term as CAS was also marked by the Federal government's decision to transfer the RAAF's battlefield helicopters to the Australian Army, against the recommendation of an independent committee. According to Air Force historians Alan Stephens and Keith Isaacs, "Newham protected the best interests of the Australian Defence Force by getting on with the business of effecting the transfer, notwithstanding the deep disappointment within his own service.[1] In February 1987, OPCOM (subsequently Air Command) was restructured into Force Element Groups (FEGs), large functional organisations that supplanted the earlier concept of all-powerful air base commands, to which every unit on a base reported.[25][26] Initially established on a one-year trial basis, the FEGs have remained in place.[26][27]

Newham completed his tenure as CAS on 3 July 1987 and was succeeded by Air Marshal Ray Funnell.[20] Retiring from the Air Force, he became Director of Helitech Industries.[2] On 23 July 1998, he was among those present when the Korean Ambassador to Australia awarded his government's Presidential Unit Citation to No. 77 Squadron.[28] Newham was one of ten surviving veterans of the squadron belatedly presented with the US Air Medal in Canberra on 27 June 2011, for meritorious service in the Korean War.[29] He died on 27 December 2022, at the age of 92.[30]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Stephens; Isaacs, High Fliers, pp. 174–176

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Air Marshals". Air Power Development Centre. Archived from the original on 1 June 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d Singh, Who's Who in Australia 2010

- ^ "Newham, John William". Nominal Roll of Australian Veterans of the Korean War. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Stephens, Australia's Air Chiefs, p. 65

- ^ Mordike, The Post War Years, pp. 40–41

- ^ Stephens, Going Solo, pp. 252, 259, 349

- ^ Hurst, Strategy and Red Ink, p. 188

- ^ Susans, The RAAF Mirage Story, p. 142

- ^ Susans, The RAAF Mirage Story, p. 128

- ^ Susans, The RAAF Mirage Story, p. 141

- ^ RAAF Historical Section, Bomber Units, p. 150

- ^ Lax, From Controversy to Cutting Edge, pp. 108–109

- ^ Lax, From Controversy to Cutting Edge, p. 121

- ^ Stephens, Australia's Air Chiefs, pp. 67–68

- ^ "RAAF appointment changes". The Canberra Times. Canberra: National Library of Australia. 28 March 1980. p. 8. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ McNamara, The Quiet Man, p. 125

- ^ Stephens, Australia's Air Chiefs, p. 73

- ^ "Newham, John William: Officer of the Order of Australia". It's an Honour. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ a b Stephens, Australia's Air Chiefs, v

- ^ Llewelyn, Ken (June 1985). "New CAS sets his sights on the future". RAAF News. Vol. 27, no. 5. p. 1.

- ^ Stephens, Power Plus Attitude, pp. 168–169

- ^ Stephens, Power Plus Attitude, p. 166

- ^ "Newham, John William: Companion of the Order of Australia". It's an Honour. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Stephens, Australia's Air Chiefs, p. 70

- ^ a b "OPCOM changes". RAAF News. March 1987. p. 1.

- ^ "Air Command". Royal Australian Air Force. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Odgers, Mr Double Seven, p. 146

- ^ "Awarding of US Air Medals to Australian Veterans of the Korean war". Department of Defence. 27 June 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ James, Marin (2 February 2023). "Farewell to the 'gentleman' Chief". Air Force. Vol. 65, no. 1. p. 5. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

References

[edit]- Hurst, Doug (2001). Strategy and Red Ink: A History of RAAF Staff College 1949–1999. RAAF Base Fairbairn: Aerospace Centre. ISBN 0-642-26558-5.

- Lax, Mark (2010). From Controversy to Cutting Edge: A History of the F-111 in Australian Service. Canberra: Air Power Development Centre. ISBN 978-1-92080-054-3.

- McNamara, Neville (2005). The Quiet Man. Canberra: Air Power Development Centre. ISBN 1-920800-07-7. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014.

- Mordike, John, ed. (1997). The Post-War Years 1945–1954: The Proceedings of the 1996 RAAF History Conference. Canberra: Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-26501-1.

- Odgers, George (2008). Mr Double Seven. Canberra: Air Power Development Centre. ISBN 978-1-920800-30-7.

- RAAF Historical Section (1995). Units of the Royal Australian Air Force: A Concise History. Volume 3: Bomber Units. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-42795-7.

- Singh, Shivani (2010). Who's Who in Australia 2010. Melbourne: Crown Content. ISBN 978-1-74095-172-2.

- Stephens, Alan, ed. (1992). Australia's Air Chiefs: The Proceedings of the 1992 RAAF History Conference. Canberra: Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 0-642-18866-1.

- Stephens, Alan (1992). Power Plus Attitude: Ideas, Strategy and Doctrine in the Royal Australian Air Force 1921–1991. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-24388-0.

- Stephens, Alan (1995). Going Solo: The Royal Australian Air Force 1946–1971. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-42803-1.

- Stephens, Alan; Isaacs, Jeff (1996). High Fliers: Leaders of the Royal Australian Air Force. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 0-644-45682-5.

- Susans, M.R., ed. (1990). The RAAF Mirage Story. RAAF Base Point Cook, Victoria: RAAF Museum. ISBN 0-642-14835-X.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch