Joseph Lyman Silsbee

Joseph Lyman Silsbee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 25, 1848 |

| Died | January 31, 1913 (aged 64) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Harvard Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse | Anna Baldwin Sedgwick |

| Awards | Peabody Medal (1894)[1] |

| Buildings | |

| Projects | Amos Block |

Joseph Lyman Silsbee (November 25, 1848 – January 31, 1913) was a significant American architect during the 19th and early 20th centuries. He was well known for his facility of drawing and gift for designing buildings in a variety of styles. His most prominent works ran through Syracuse, Buffalo and Chicago. He was influential as mentor to a generation of architects, most notably architects of the Prairie School including the famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

Early life

[edit]Joseph Lyman Silsbee was born on November 25, 1848, in Salem, Massachusetts. Silsbee graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy in 1865[2] and Harvard in 1869.[2] In 1870,[3] he became an early student of the first school of architecture in the United States at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Career

[edit]After graduating from Harvard and MIT, he served an apprenticeship with Boston architects William Robert Ware & Henry Van Brunt and William Ralph Emerson, respectively. Silsbee traveled around Europe before moving to Syracuse, New York in 1874. In 1875, he married Anna Baldwin Sedgwick, daughter of influential lawyer and politician Charles Baldwin Sedgwick. He had a prolific practice and at one point had three simultaneously operating offices. He had offices in Syracuse (1875–1885), Buffalo (Silsbee & Marling, 1882–1887), and Chicago (Silsbee and Kent, 1883–1884). From 1883 to 1885, his Syracuse office was a partnership with architect Ellis G. Hall. Silsbee's Chicago office had a number of architects who were later to become known in their own right, including:

- Frank Lloyd Wright[4]

- George Grant Elmslie[5]

- George W. Maher

- Irving J. Gill

- Henry G. Fiddelke[6][circular reference]

Silsbee was one of the first professors of architecture at Syracuse University, another one of the earliest schools of architecture in the nation. He was a founding member of the Chicago and Illinois Chapters of the American Institute of Architects. In 1894, Silsbee was awarded the Peabody Medal by the Franklin Institute for his design for a Moving Sidewalk.[1] This invention had its debut at the Worlds Columbian Exposition and saw usage in subsequent Worlds Fairs.

Style of architecture

[edit]Among his most prominent architectural works is the landmark Syracuse Savings Bank Building (1876). Built next to the Erie Canal on Clinton Square in Syracuse, it is often referred to as a textbook example of the High Victorian Gothic style. Silsbee also designed the White Memorial Building (1876), the Amos Block (1878), and the Oakwood Cemetery Chapel (1879–80), all extant in Syracuse. Upland Farm (1892), the lost mansion designed for Frederick R. and Dora Sedgwick Hazard in nearby Solvay, New York, is an example of the fashionable residential work that Silsbee was best known for. Silsbee also designed various dwellings around New York State in Ballston Spa, Albany, and Peekskill (in the latter place for Henry Ward Beecher)[7]

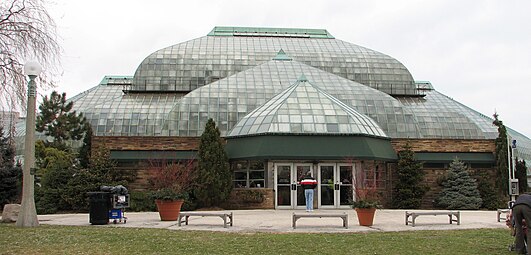

Silsbee designed the lavish interiors of Potter Palmer's "castle" in Chicago. Several of his residential designs survive in Riverside and Evanston Illinois. His most prominent surviving work in Chicago is the Lincoln Park Conservatory. Considerably smaller in scale but filled with such elegant details as mosaic floors and a graceful oak roof with "hammer-beams trusses and curved brackets" is his Horatio N. May Chapel on the grounds of Rosehill Cemetery.[8] Silsbee designed the movable walkway at the World's Columbian Exposition pier in 1893, and submitted plans to provide this improvement for the Brooklyn Bridge in 1894,[9] although these plans were never executed.

In his 1941 autobiography, Frank Lloyd Wright wrote:

Silsbee could draw with amazing ease. He drew with soft, deep black lead-pencil strokes and he would make remarkable free-hand sketches of that type of dwelling peculiarly his own at the time. His superior talent in design had made him respected in Chicago. His work was a picturesque combination of gable turret and hip with broad porches quietly domestic and gracefully picturesque. A contrast to the awkward stupidities and brutalities of the period elsewhere.[10]

Silsbee practiced architecture until his death in 1913.

Works

[edit]Works include:

| Building | Image | Dates | Location | City, State | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| William S. Warfield House |  | 1886 built 1979 NRHP-listed | 1624 Maine St. 39°55′53″N 91°23′23″W / 39.931389°N 91.389722°W | Quincy, Illinois | Built in 1886 on Maine Street in a blend of the Richardsonian Romanesque and Queen Anne styles. The house features a stone exterior with terra cotta decorations, a massive plan, and a large western porch as well as several smaller porches throughout.[11] |

| Bryant H. and Lucie Barber House |  | c. 1901 built 1993 NRHP-listed | 103 North Barber Avenue 41°59′11″N 89°34′54″W / 41.986389°N 89.581667°W | Polo, Illinois | Constructed around 1901, the house has brick walls, a stone foundation and incorporates steel into its construction.[12] |

| Henry D. Barber House |  | c.1891 built 1974 NRHP-listed | 410 West Mason Street 41°59′11″N 89°34′56″W / 41.986482°N 89.58236°W | Polo, Illinois | Designed by Silsbee and constructed around 1891, with minor alterations in 1899,[13] the brick and limestone home is cast in Classical Revival style.[13] |

| Amos Block |  | 1878 built 1978 NRHP-listed | 210-216 West Water Street 43°03′02″N 76°09′17″W / 43.050556°N 76.154722°W | Syracuse, New York | Romanesque Revival building formerly fronting on the Erie Canal, from which goods were loaded and unloaded from boats[14] |

| Syracuse Savings Bank |  | 1875 built 1971 NRHP-listed | 102 N. Salina St.43°03′03″N 76°09′08″W / 43.050833°N 76.152222°W | Downtown Syracuse, New York | Designed by Silsbee; built in 1875 adjacent to the Erie Canal; its passenger elevator, the first in Syracuse, was an attraction[15] |

| White Memorial Building |  | 1876 built 1973 NRHP-listed | 100 E. Washington St. 43°02′58″N 76°09′09″W / 43.049444°N 76.1525°W | Syracuse, New York | Prominent, 1876-built, Gothic building with "exceedingly pleasant" dissimilatudes[16] |

| Unity Chapel |  | 1886 built 1974 NRHP-listed | S of Spring Green off WI 23 43°07′57″N 90°03′39″W / 43.1325°N 90.060833°W | Spring Green, Wisconsin | Shingle style rural Wisconsin family chapel for the Chicago Unitarian minister Jenkin Lloyd Jones, designed by Silsbee (who was also building a Chicago church for him), with interior work left to Jones' young nephew Frank Lloyd Wright.[17] |

| Charles H. Sedgwick House | 1884 built c.1925 demolished | James St. | Sedgwick neighborhood, Syracuse, New York | Its roof had a "unique double-gable, a motif also seen on Silsbee's Thomas Drummond Home, built about a year later." Was built for Silsbee's brother-in-law, Charles Hamilton Sedgwick.[18] | |

| Thomas Drummond Home |

Gallery

[edit]- Lincoln Park Conservatory, Chicago, IL

- Syracuse Savings Bank Building

- White Memorial Building, in Syracuse, New York

- Upland Farm, the Frederick R. Hazard residence built in 1891

- Amos Block, also in Syracuse

- Mortuary chapel, Oakwood Cemetery, Syracuse, New York

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "JOSEPH L. SILSBEE". fi.edu. 11 January 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ a b "General catalogue of officers and students, 1783-1903. (page 10 of 31)". Phillips Exeter Academy. Retrieved 2011-01-13.

- ^ "Joseph Lyman Silsbee". Archived from the original on 2022-01-02.

- ^ Andrews, Wayne (November 6, 1966). "Paperbacks: Architecture". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Joseph L Silsbee". Archived from the original on 2020-08-10. Retrieved 2007-01-01.

- ^ John L. Pentecost House

- ^ LaChiusa, Chuck. "Falconwood". buffaloah.com. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ "Costly Tombs of the Rich." Chicago Tribune. August 19, 1900.

- ^ "Movable Walk for the Big Bridge - Chicago Speed to be Applied to the present Slow Transportation Facilities". Chicago Daily Tribune: 8. April 20, 1894.

- ^ Wright, Frank Lloyd (1941). Frank Lloyd Wright On Architecture: Selected writings on architecture between 1894 and 1940. Duell, Sloan and Pearce. p. 275. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Karlowicz, Titus M. (October 1978). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form: William S. Warfield Residence" (PDF). Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-06. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ^ Bryant H. and Lucie Barber House[permanent dead link], "Property Information Report", HAARGIS Database, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, accessed January 22, 2011.

- ^ a b Henry D. Barber House[permanent dead link], "Property Information Report", HAARGIS Database, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, accessed January 22, 2011.

- ^ Miller, Ellen R. (August 30, 1978). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Amos Block". Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved 2008-12-26. and Accompanying 18 photos, exterior and interior, from 1977, 1978, and undated Archived 2011-12-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Waite, Diana S. (August 1970). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Syracuse Savings Bank". Archived from the original on 2011-12-10. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ^ T. Robins Brown (April 1972). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: White Memorial Building". Archived from the original on 2011-12-10. Retrieved 2010-01-08. and Accompanying two Historic American Buildings Survey photos, exterior, from 1962 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Unity Chapel". National Register or State Register. Wisconsin Historical Society. January 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ^ "Home for Charles H. Sedgwick". 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Syracuse-Onondaga County Planning Agency (1975). Onondaga Landmarks.

- Harley McKee, Patricia Earle, Paul Malo (1964). Architecture Worth Saving in Onondaga County. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

- Angela Hess. "Joseph Lyman Silsbee" at the Wayback Machine (archived June 27, 2004)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch