Kandyan Wars

| Kandyan Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

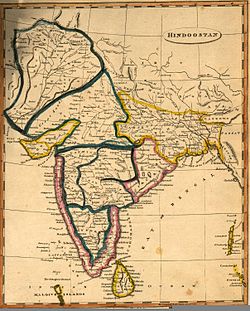

Hindoostan on the eve of the Second Kandyan War; the entirety of Sri Lanka is shown as being under British control, when in fact the kingdom of Kandy endured in the mountainous interior. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Kingdom of Kandy's Army | Green Howards 19th Regiment of Foot King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry 51st Regiment of Foot Ceylon Rifle Regiment | ||||||

| History of Kandy |

|---|

|

| Kingdom of Kandy (1469–1815) |

| Colonial Kandy (1815–1948) |

| Kandy (1948–present) |

| See also |

| |

The Kandyan Wars (or the Kandian Wars) refers generally to the period of warfare between the British colonial forces and the Kingdom of Kandy, on the island of what is now Sri Lanka, between 1796 and 1818. More specifically it is used to describe the expeditionary campaigns of the British Army in the Kingdom of Kandy in 1803 and 1815.

Background

[edit]From 1638–58, the Dutch East India company had intervened in the Sinhalese–Portuguese War, capturing all the Portuguese possessions on the island of Ceylon (now called Sri Lanka). They established the colony of Dutch Ceylon, controlling the coasts and lowlands, whilst the Kingdom of Kandy maintained their independence in the mountainous eastern interior. In 1795 the Dutch Republic was overthrown with French assistance, forming the Batavian Republic as a puppet state. Britain, which was at war with France, feared that influence would result in French control or use of the strategically important port of Trincomalee and others on the island. Following the Kew Letters of 1795, the British occupied Dutch possessions in Sri Lanka. These included not only Trincomalee but Batticaloa, Galle, and Jaffna, as well as the entirety of Sri Lanka's lowlying coastal areas. The new colony of British Ceylon was determined to expand and control the entirety of the island, and had reformed traditional social structures like the caste system and the rajakariya (lit. "kingwork", labour and or tithes owed to the Kandyan king). This added to the tension between them and the still independent Kingdom of Kandy.

Mountainous central Sri Lanka remained independent, having resisted 250 years of European attempts to control Ceylon. Kandy was now under the rule of the Nayaka kings of Senkadagala. Early British attempts at securing a treaty with mountainous kingdom were rejected.[1] The internal stability of Kandy was shaky, as king Sri Vikrama Rajasinha found himself being constantly undermined and intrigued against by powerful Sinhalese nobles. He also faced a potential usurper in the form of Muttusami, brother-in-law of the previous king Rajadhirajasingha, who had fled to British controlled lands in the early 19th century and had been agitating against the beleaguered king ever since.[2]

The earliest British garrison numbered about 6,000 which was increased through the recruitment of local sepoys, and the forces of the Empire further enjoyed exclusive access to the sea. Kandy, in contrast, had the advantage of being situated in difficult, mountainous terrain, and could also draw on four hundred years of experience fighting European colonial powers.[citation needed]}

History

[edit]First war (1803–1805)

[edit]

The first Kandyan war was precipitated by the intrigues of a minister of Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, Pilimatalawe, who defected to the British and offered to show them the way through central Sri Lanka's winding mountain passes to the capital city. Enraged, the King of Kandy had the minister's family executed.

The British dispatched two separate forces into Kandyan territory - one, under Major-General Hay MacDowall, from Colombo, and another, under a Colonel Barbut, from Trincomalee. These included 51st Regiment of Foot, the 19th Regiment of Foot, the Malay (Muslim) 1st Ceylon Regiment, the all-Sinhalese 2nd Ceylon, and the mixed Sinhalese Malay 3rd Ceylon. In the Kandyan army, at least one contingent was under the command of a Malay Muslim prince called 'Sangunglo',[3] an indicator of the multiethnic nature of the mountainous kingdom. After fierce fighting the British force found Senkadagala deserted in February 1803. They swiftly established a garrison, crowned Muttusami as the new, puppet, king of Kandy, and set about subduing the remainder of the kingdom.

Despite these early successes the army soon suffered a number of setbacks. The Chief Minister responsible for guiding the British into Kandy had greatly inflated the extent of the king's unpopularity, and resistance proved fierce. The Kandyans resorted to fighting a guerilla war (much the same tactic as they had adopted against the Portuguese and the Dutch) and proved difficult to dislodge. Disease ravaged the garrison left behind in Senkadagala to secure the capital. Perhaps most worrying for them, a number of native sepoys defected to the Kandyans, including a soldier of Malay descent called 'William O'Deen' or 'Odeen', who years later became the first Sri Lankan exiled to Australia.[4][5]

The Kandyans counter-attacked in March and seized Senkadagala. Barbut was taken prisoner and executed, and the British garrison wiped out; only one man, Corporal George Barnsley of the 19th Infantry, survived to tell the tale (though other sources put the number of survivors at four).[6] In the meanwhile the retreating British army was defeated on the banks of the flooding Mahaveli river, leaving only four survivors.[7]

Despite this setback the British still remained unquestioned masters of the lands they possessed, as the disastrous Kandyan counter-campaign later in the year proved. Equipped with a handful of captured six-pound cannon, the Kandyan army advanced through the mountain passes as far as the city of Hanwella.[8] Here the army was utterly routed by superior British firepower, forcing Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe to flee back into the mountains. A general rebellion that had erupted in British-controlled territory on hearing of the Kandyan invasion was suppressed.

Frederick North, governor of Ceylon from 1798–1805, maintained pressure on the Kandyan frontier with numerous attacks, in 1804 dispatched a force under Captain Arthur Johnston towards Senkadagala. In a pattern that had become clear over the past two hundred or so years, the Kandyans once again defeated the British in the mountainous territory they called home. In 1805, emboldened by their successes, they captured Katuwana, a frontier town. This and the 1803 victory at the Battle of the Mahaveli, were to be Kandy's last, meaningful military successes.

Though no treaty was signed officially ending the First Kandyan War, the appointment of General Thomas Maitland as governor of Ceylon in 1805 is generally accepted as the end of this first phase of open hostilities.

Interbellum (1805–1815)

[edit]Events in the ten years between the end of the First Kandyan War and the Second were such that the complexion of the second conflict was quite different from the first. Whereas in 1805 the British had been forced to contend with a largely hostile native nobility, in 1815 it was this same nobility who essentially invited the British into Kandy and supported their overthrow of Sri Vikrama Rajasingha.

Governor Thomas Maitland, in British Ceylon, initiated extensive legal and social reforms to further entrench and strengthen British power. These included the reform of the civil service to eliminate corruption, and the creation of a Ceylonese High Court based on caste law. The Catholic population was enfranchised whilst the Dutch Reformed church lost its privileged position. Maitland also worked to undermine Buddhist authority and sought to attract Europeans to the island by allowing grants of up to 4000 acres (16 km²) on the island.[2] He was replaced in 1812/1813 by Sir Robert Brownrigg,[9] who largely continued these policies.

In contrast, an increasingly paranoid Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe categorically alienated Kandy's powerful nobility and volatile commoners. The construction of Kandy Lake was completed in 1807. Despite its beauty it was a deeply unpopular project, as it served no practical purpose - central Senkadagala had no paddy fields that required irrigation, the traditional cause for the construction of such hydraulic monuments. In 1810 he removed the powerful Pilima Talauve from the position of Chief Minister (1st Adigar). Talauve rebelled the following year and much to the horror of Kandy's nobles was executed.[8] The king further alienated the powerful Buddhist establishment with arbitrary requisitions of land and treasure.[10] Throughout this period John D'Oyly, a British civil servant, was in close contact with various Sinhala nobles, who increasingly seemed to prefer the rule of the British to the volatile government of the Nayaka monarchy.

Second war (1815)

[edit]The train of events leading directly up to the 1815 war commenced with the humiliation of Ehelepola, Pilima Talauve's nephew and successor as First Adigar. Ehelepola had been involved in several intrigues against the by now deeply unpopular Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe since his appointment in 1810. In 1814 his actions were revealed and the noble fled to British territory. The furious king had Ehelepola's entire family put to death in various gruesome ways. Ehelepola came to symbolize weaknesses of part of the Sri Lankan nobility which assisted in colonisation, and thought of as a great traitor in modern Sinhalese popular thought. Also such siding with European powers is seen of as the key weakness in the subcontinent which enabled colonisation itself.[11] The deaths shocked the Kandyan aristocracy who now openly revolted against the king, who torched his palace and fled to a fortress at Hanguranketha.

John d'Oyly, in the meanwhile, had been advising Governor Brownrigg for some time that Kandy's nobles were ready to cooperate with any British attempt at dislodging Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe. Kandyan troops soon crossed the British-Kandyan border seeking Ehelepola, and attacked the British garrison at Sitawaka - of itself enough provocation for Brownrigg to dispatch a force to Kandy.[6] The situation was only worsened by the arrival of a group of British traders who Sri Vikrama Rajasingha had ordered mutilated at Hanguranketha.[11]

The British forces met scant resistance and entered Kandy on the 10 February, 1815, accompanied by John d'Oyly; Brownrigg informed the Admiralty that 'Let by the invitation of the chiefs and welcomed by the acclamations of the people, the forces of His Britannic Majesty, have entered the Kandyan territory and penetrated to the capital. Divine Providence has blessed their efforts with uniform success and complete victory. The ruler of the interior provinces has fallen into their hands and the government remains at the disposal of His Majesty's Representative'.[12] Sometime later Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe's hiding place was discovered; the deposed king was exiled with his harem, to Vellore Fort in India, where he died 17 years later. His son, and potential heir, died childless in 1842.

The single most important event following the arrival of British forces in Kandy was the signing of the Kandyan Convention. Essentially a treaty of annexation, it was agreed to in March 1815 after negotiations between John d'Oyly and the nobles of Kandy. The central points of the agreement were:

- 'Sri Wickrema Rajasinha', the 'Telugu' king, is to forfeit all claims to the throne of Kandy.

- The king is declared fallen and deposed and the hereditary claim of his dynasty, abolished and extinguished.

- All his male relatives are banished from the island.

- The dominion is vested in the sovereign of the British Empire, to be exercised through colonial governors, except in the case of the Adikarams, Disavas, Mohottalas, Korales, Vidanes and other subordinate officers reserving the rights, privileges and powers within their respective ranks.

- The religion of Buddhism is declared inviolable and its rights to be maintained and protected.

- All forms of physical torture and mutilations are abolished.

- The governor alone can sentence a person to death and all capital publishments to take place in the presence of accredited agents of the government.

- All civil and criminal justice over Kandyan to be administered according to the established norms and customs of the country, the government reserving to itself the rights of interposition when and where necessary.

- Other non-Kandyan's position [is] to remain [as privileged as previously] according to British law.

- The proclamation annexing the Three and Four Korales and Sabaragamuwa is repealed.

- The dues and revenues to be collected for the King of England as well as for the maintenance of internal establishments in the island.

- The Governor alone can facilitate trade and commerce.

The signatories of the convention were Governor Brownrigg, Ehelepola and the lords (called 'Dissawes' in Sinhalese) Molligoda, Pilimatalawe the Elder, Pilimatalawa the Younger, Monerawila, Molligoda the Younger, Dullewe, Ratwatte, Millawa, Galgama and Galegoda. The signatures were witnessed by d'Oyly, who became British Resident and effective governor in the area, and his private secretary James Sutherland.

The convention is interesting in many ways. It represents the theoretically voluntary transferral of authority in Kandy to the British, and indeed later events showed that the Kandyan nobility did hope that they were simply replacing one malleable master (the Nayakkar monarchy) with another (the British). Indeed, Ehelepola appears to have hoped that the new master would not be the British at all, but himself.[8]

The nobles and religious potentates of Kandy were also adamant in including clause 5 concerning the protection of Buddhism. Later in 1815 the heads of the Buddhist monasteries at Malwatte and Asgiriya both met Governor Brownrigg and extracted guarantee that Buddhism would not be compromised.[13] This included a ban on proselytising and mission schools.

Third war (1817–1818)

[edit]It took the ruling families of Kandy less than two years to realise that the authority of the British government was of a fundamentally different type to that of the (deposed) Nayakkar monarchy. Discontent with British activities soon boiled over into open rebellion, commencing in the duchy of Uva in 1817. Generally called the 'Uva Rebellion', it is also known as the Third Kandyan War. In many ways the third name is more appropriate, as the rebellion (which soon developed into a guerilla war of the kind the Kandyans had fought against European powers for some time) was centred on the Kandyan nobility and their unhappiness with developments under British rule since 1815. However it is the last uprising of this kind and Britain's response essentially abolished the old aristocracy and ensured future rebellions would take on a much more subdued character.

The Ceylon Medal was instituted by the Ceylonese Government in 1819, the only gallantry medal struck for the Kandyan Wars.[14]

Legacy

[edit]The British capture of the kingdom of Kandy marked not only the end of the 400-year-old Kingdom of Kandy, but also of all native political independence. Kandy, as a result of its geographical and political isolation, had developed unique cultural and social structures that were now subject to the intense pressures of outside rule and underwent immense upheaval and change.

Before 1815, much of Kandy's territory had been underdeveloped with unreliable dirt-track roads for access, apart from a few 'royal roads'. The British proceeded to transform the hill country by constructing roads across previously inaccessible terrain (such as the Kadugannawa Pass), and, in 1867, building the first railway. The other big transformation was the introduction of tea to central Sri Lanka in 1867 and the massive settlement of Tamils in the region. Central Sri Lanka is now dominated by the vast tea estates that helped make Sri Lanka the world's biggest exporter of tea for a while, and were still owned by British companies in 1971.

A lasting legacy of the same war in Ireland is the traditional anti-war and anti-recruitment song "Johnny I Hardly Knew Ye", depicting a soldier from Athy, County Kildare who comes home horribly mutilated from the war in "Sulloon" (Ceylon).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Coddrington, Humphrey Eilliam (1926), "10", A Short History of Lanka, London: Macmillan & Co. Retrieved on 23 August 2008.

- ^ a b "san.beck.org". Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Malays". Rootsweb.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "LANKALIBRARY FORUM • View topic - Malayan Drum Major Odeen -1st Ceylonese Soldier in Australia". Lankalibrary.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "Online edition of Sunday Observer - Business". Sundayobserver.lk. 2003-06-29. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ a b "Toolserver:Homepage". Answers.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "The Newsletters of the Friends of the Green Howards Regimental Museum". Archived from the original on 2006-06-15. Retrieved 2006-07-03.

- ^ a b c [1] Archived February 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Robert Brownrigg: Information from". Answers.com. 2009-12-27. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ Sri Lanka. "AllRefer.com - Sri Lanka - The British Replace the Dutch | Sri Lankan Information Resource". Reference.allrefer.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ a b "Ehelepola Medduma Bandara". Lankalibrary.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "WWW Virtual Library - Sri Lanka: Haputale". Lankalibrary.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "The 1815 Kandyan Convention at the Audience Hall". Rootsweb.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ Walsh, Robin. "16 June 1818: deaths of Private James Sutherland and Private William Chandler (73rd Regt)". Under a Tropical Sun. Macquarie University. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Powell, Geoffrey (1973), The Kandyan Wars, London

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pieris, Ralph (1956), Sinhalese Social Organization: The Kandyan Period, Colombo

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wickremesekara, Channa (2004), "Military Organisation in Pre-Modern Sri Lanka: The Army of the Kandyan Kings", The Journal of South Asian Studies, XXVII (2 August 2004): 133–151, doi:10.1080/1479027042000236616, S2CID 144325717

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch