Kazys Grinius

Kazys Grinius | |

|---|---|

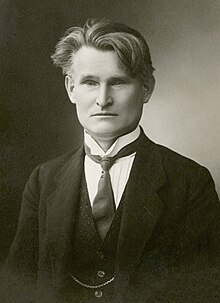

Grinius in 1926 | |

| 3rd President of Lithuania | |

| In office 7 June 1926 – 17 December 1926 | |

| Preceded by | Aleksandras Stulginskis |

| Succeeded by | Jonas Staugaitis (acting) |

| 6th Prime Minister of Lithuania | |

| In office 19 June 1920 – 18 January 1922 | |

| President | Aleksandras Stulginskis |

| Preceded by | Ernestas Galvanauskas |

| Succeeded by | Ernestas Galvanauskas |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 17 December 1866 Selema, Augustów Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 4 June 1950 (aged 83) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Political party | Lithuanian Popular Peasants' Union |

| Spouse(s) | Joana Pavalkytė-Griniuvienė Kristina Arsaitė-Grinienė |

| Children | Liūtas Grinius (died 1989) |

| Alma mater | Imperial Moscow University (1893) |

| Signature | |

| Righteous Among the Nations |

|---|

|

| By country |

Kazys Grinius ([kɐˈzʲiːs ˈɡʲrʲɪnʲʊs] , 17 December 1866 – 4 June 1950) was the third President of Lithuania, holding the office from 7 June 1926 to 17 December 1926.[1][2] Previously, he had served as the fifth Prime Minister of Lithuania, from 19 June 1920 until his resignation on 18 January 1922. He was posthumously awarded the Lithuanian Life Saving Cross for saving people during the Holocaust and was recognised as a Righteous Among the Nations in 2016.[3]

Grinius was born in Selema, near Marijampolė, in the Augustów Governorate of Congress Poland, which was part of the Russian Empire. He studied medicine at the Imperial Moscow University and became a physician. As a young man, he became involved in Lithuanian political activities, and was persecuted by the Tsarist authorities. In 1896, he was one of the founders of the Lithuanian Democratic Party (LDP) and Lithuanian Popular Peasants' Union (LVLS) party. That same year he married Joana Pavalkytė. For some time they lived in Virbalis. In 1899, their son Kazys (later head of the Lithuanian National Council)[4] was born, and in 1902, their daughter Gražina was born. During World War I they lived in Kislovodsk. In 1918, during a Red Army attack, his wife and daughter were murdered by Russian terrorists.[2] They were buried in Kislovodsk cemetery.

When Lithuania regained its independence in 1918, Grinius became a member of the Constituent Assembly as a member of the Lithuanian Popular Peasants' Union party. He served as prime minister from 1920 until 1922,[1][2] and signed a treaty with the Soviet Union. He was elected president by the Third Seimas, but served for only six months, as he was deposed in a coup led by Antanas Smetona on the pretext of an imminent communist plot to take over Lithuania.[2] Grinius then practiced medicine in Kaunas.[2] When Nazi Germany invaded Lithuania in 1941, Grinius refused to collaborate with the Germans because of his opposition to the occupation of Lithuania by any foreign power. He fled to the West when the Soviet army reoccupied Lithuania in 1944, and he emigrated to the United States in 1947.[1][5]

He died in Chicago in 1950.[1][2][5] After Lithuania regained its independence in 1990, his remains were returned and buried near his home village.

Early life

[edit]Family

[edit]Of noble (szlachta) lineage, the Griniai family moved to the region of Suvalkija during the Volok Reform of 1560. Kazys Grinius was born on 17 December 1866, in the village of Selema, then known as Selemos Būda. The village belonged to the Augustów Governorate of Congress Poland, then part of the Russian Empire. Grinius was the third child out of the family's eleven (two of whom would die in infancy). His father, Vincas Grinius (1837–1915) was a farmer who owned 15 hectares of land. A nephew of writer and leader of the January Uprising Mikalojus Akelaitis, Vincas could speak Russian and Polish, and owned a small library containing prayer books and the works of Laurynas Ivinskis, Motiejus Valančius and Petras Vileišis.[6] Grinius's mother Ona Griniuvienė née Vosyliūtė (1839–1919) was a strict and religious Catholic. Two of Grinius' siblings, Jonas Grinius (1877–1954)[7] and Ona Griniūtė-Bacevičienė (1884–1972)[8] were book smugglers during the Lithuanian press ban. Ona's nephew Vytautas Bacevičius-Vygandas was an officer in the Lithuanian Liberty Army, Povilas Plechavičius's Lithuanian Territorial Defense Force, as well as chief of headquarters of the Tauras military district of the Lithuanian partisans.[9]

School years (1876–1887)

[edit]Grinius learned to read from his mother, and to count and write from his father. In 1876, at the age of nine, Grinius began to attend the Oszkinie Russian primary school, three months later switching to school in Gudeliai. He also attended school in Marijampolė before being accepted at the Marijampolė Gymnasium in 1879 at the age of twelve. Since the Lithuanian language in the region wasn't banned but rather acted as an optional school subject, Grinius mostly spoke Polish with his classmates before beginning to attend Lithuanian classes in third grade. His tutors were Petras Arminas-Trupinėlis and Petras Kriaučiūnas. Inspired by the release of the first Lithuanian newspaper Aušra in 1883, Grinius and future poet Jonas Mačys-Kėkštas published their own newspaper entitled Priešaušris. Grinius was also adamant that prayer would be conducted in Lithuanian rather than Polish. Grinius then began smuggling Aušra and other illegal publications, sometimes bringing them from Prussia by himself.[10]

Studies and activism (1887–1914)

[edit]After graduating in 1887, Grinius began studying medicine at Moscow State University, where he became a member of a secret society of Lithuanian students. He was its chairman from 1889 until his graduation. The society organized self-education and self-sufficiency of students and distributed Lithuanian press, cooperating with Latvian and Polish student societies. Grinius suggested that the 300 rubles the society won through a lottery should be used for the publication of Lithuanian books; the students subsequently established a fund to publish Lithuanian books (Fondas lietuvių knygoms leisti). Grinius also published his first article in a United States-based newspaper Lietuviškasis balsas. In 1888 at the age of twenty-two, along with Vincas Kudirka, Grinius and six others participated in a gathering in Marijampolė, in the so-called first congress of Lithuanian democrats, where they decided to begin the publication of the newspaper Varpas. In 1893, he was elected member of the Varpininkai organization committee. Grinius organized the publishing of Ūkininkas. Along with other students he wrote A Short History of Ancient Lithuanians (Trumpa senovės Lietuvių istorija), which was published in 1892 in Tilsit (modern-day Sovetsk). During vacation, Grinius would travel across Lithuania and distribute Lithuanian newspapers, lead "anti-state propaganda", and collect folklore. As a member of the 1899 Russian student strike, Grinius was arrested for 9 days and put in Butyrka prison. In 1892, he was a doctor who treated cholera patients in Minsk. During his study years, Grinius lived a poor and ascetic life. After graduating, Grinius did not have enough money to settle in Lithuania, and so became a ship doctor in the Caspian Sea for about nine months.[11]

After returning to Lithuania in 1894, Grinius earned a living as a free-for-hire doctor in Marijampolė. After two years he moved to Virbalis, and later to Kudirkos Naumiestis. Grinius helped establish the Social Democratic Party of Lithuania in 1896, preparing its first newspaper Lietuvos darbininkas and translating the party's program from Polish into Lithuanian. He also was one of the establishers of the Lithuanian Democratic Party in 1902 who prepared its program in 1906, as well as writing the program of the Peasant Union. An active member of the Lithuanian Popular Socialist Democratic Party, Grinius edited the last edition of Varpas. From 1898 to 1902 he lived in Pilviškiai, replacing Stasys Matulaitis as the local book smuggler. From 1897 to 1899 he edited the newspaper Ūkininkas. After returning to Marijmapolė, he was briefly imprisoned for Lithuanian cultural activism. His family home became a center of the Lithuanian cultural movement in the region of Užnemunė (west of the Nemunas river).[10] Grinius helped write petitions from local peasants to the governor of the Suwałki Governorate. In his opinion, these few years when Lithuanians became more culturally active became the foreground for the Great Seimas of Vilnius. In 1905, he lived in Vilnius, moving back to Marijampolė in 1906 only to be imprisoned along with his wife for two weeks.[12]

Grinius was also one of the founding members of Šviesa in 1905, a society dedicated to the establishment of schools, pedagogical evening courses, bookstores, distribution of Lithuanian publications, and assisting young students. Although the society was illegal and soon had to be closed down, it was made legal again in 1907 and expanded into as many as twenty-three chapters in the Suwałki Governorate. Nonetheless the society experienced a search by Tsarist authorities in 1908, after which Grinius among many others were arrested and imprisoned in a prison in Kalvarija. After that, Grinius's family was ordered to leave their home, after which they moved to Vilnius. The society was fully liquidated in 1911.[13] In 1906, a text he wrote entitled "The Correct Land Management in Lithuania" (Teisingas žemės valdymas Lietuvoje) was published as a separate book which contained many ideas that were to be found later in the 1922 Lithuanian land reform.[14] From 1908 to 1910 he lived in Vilnius. In 1909, along with Gabrielė Petkevičaitė-Bitė he edited Lietuvos žinios, and in 1910, he edited Lietuvos ūkininkas with Albinas Rimka.[15] Once again, he was imprisoned in Marijampolė for a month and a half. A member of the secret book smuggling Sietynas organization,[16] Grinius also published on topics such as botany, medicine, and history.[17]

First World War

[edit]During the First World War Grinius and his family moved away from the front deeper into Russia. He arrived in the northern Caucasus in 1915, and worked there until 1918, firstly at Nalchik and then as head doctor in a war hospital near Grozny. While in the Caucasus, Grinius took care of Lithuanian refugees. In 1917, Grinius, Jonas Jablonskis, and Pranas Mašiotas established the Supreme Council of Lithuanians in Russia in Voronezh, whose purpose was to unite all political parties under a new authority. During the start of the Russian Civil War Grinius and his family lived in Kislovodsk, where Bolshevik forces shot his wife and fatally injured his daughter on 8 October 1918. They were buried in the nearby Orthodox cemetery. Grinius and his two sons, Kazys and Jurgis, fled to Novorossiysk, from where he boarded a ship to the Mediterrannean Sea to travel to France, before returning to Lithuania in November. Jurgis at this point was sick, and died not having reached Lithuania. He is buried in southern France.[18]

Political career

[edit]Constituent Assembly (1920)

[edit]In 1919, Grinius was chairman of the Paris-based Lithuanian Repatriation Commission which helped Lithuanian prisoners of war in Germany return home. That same year he returned to Lithuania to prepare for Constituent Assembly of Lithuania's elections as leader of a bloc between the Lithuanian Popular Socialist Democratic Party and the Peasant Union. During the election campaign, Grinius criticized the Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party. Grinius actively advocated convening the parliament mentioned in the Act of Independence of Lithuania, which was supposed to determine the nature of the structure of the country, criticizing the delay of the right-wing parties in convening it, using the Estonians as an example who elected the parliament in 1919. In 1920, he was elected to the city council of Marijampolė, becoming its chairman. After the Kaunas garrison mutiny he urged president Antanas Smetona to hold elections as quickly as possible.[19] The elections were held on 14–15 April, with Grinius's bloc getting second place before the Christian Democratic Party. Grinius urged the assembly's speaker Aleksandras Stulginskis to leave his party and prepare laws carefully. Grinius defended the interests of minorities; he proposed to include Polish representatives in the commission's work, and to allow the Jews to speak in the language of their choice. He also formed a resolution in which it was stated that the death penalty would not be done until amnesty was declared. On 19 June 1920, Grinius became the prime minister of the Christian Democrat and Peasant Union-led government coalition, a title he kept until 2 February 1922.[20]

Prime minister (1920–1922)

[edit]During his tenure, Grinius's government finished negotiations with the Soviet Union by signing a peace treaty, finalized the border with Poland, and rejected Paul Hymans's suggested union with the country. Lithuania was also accepted into the League of Nations. The tax system was reformed, hospitals and schools were established and expanded, and public transport was developed. Funds were allocated for the establishment of the Lithuanian Drama Theater and the conservation of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis's paintings, and the Vytautas Magnus University (then the University of Lithuania) was founded. Corruption was fought and preparatory works for land reform were completed. However, the government coalition dissolved as the Christian Democrat Party, which sought to recover land for the Catholic church that was confiscated and given to the Orthodox in the Russian Empire, disagreed with the Peasant Union. On 13 January 1922, a fraction of the Peasant Union discharged Grinius from the position of prime minister, with Grinius officially resigning on 18 January. The government was succeeded by Ernestas Galvanauskas's cabinet of ministers.[21]

Member of the Seimas (1922–1926)

[edit]After his resignation, Grinius continued to be an active member of the Lithuanian Seimas. He helped prepare the permanent Lithuanian constitution, which was initiated on 1 August 1922. That same year, he became the head of the medical and sanitation department of the Kaunas city municipality. As a representative of the Lithuanian Popular Peasants' Union, Grinius was elected to the first, second, and third Seimas. Grinius was a member of the political opposition who defended freedom of the press, minority rights, advocated for bigger attention to healthcare and education, and criticized peoples' such as Vincas Krėvė-Mickevičius, Augustinas Voldemaras, Antanas Smetona, and Juozas Purickis call to focus diplomatic efforts towards the USSR; it was hoped that this way Lithuania could get the Vilnius region back under its control and defend itself from Poland. In 1924, Grinius published an article entitled Mūsų rusofilai (Our Russophiles) in which he wrote that, "It's naive to believe that the USSR, which hasn't abandoned in Tsarist Russian imperialism, will give Vilnius to Lithuania", encouraging the government to rather ally itself with Great Britain and other Baltic countries.[22]

President (1926)

[edit]On 7 June 1926, Grinius was elected President of Lithuania. During his tenure, Grinius enacted a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union, by which it recognized Lithuanian rights to the Vilnius region. Savings were also allocated to road construction, industry, education, and cultural affairs. Martial law and restrictions on censorship were abolished. The country also began trade negotiations with Germany and the Soviet Union.[23] As president, Grinius did not use state transportation, preferring to travel to villages in passenger cars. When family would inquire about his choice, Grinius would respond that the Lithuanians live too poorly.[24] However, Grinius's democratic reforms were met with disapproval from conservatives. Kazys Škirpa's army reforms caused resentment from the officers as well.[25]

Coup d'état

[edit]On 17 December 1926, on the evening of Grinius's birthday, a coup was arranged that replaced the government with an authoritarian one headed by the Lithuanian Nationalist Union, the most conservative party at the time. Grinius called the coup a crime against society, and blamed the nationalists, Christian Democrats, and part of the army for it, stating that the factual and psychological reasons for the coup were deep, reaching back to the first years of independence, when nationalists who represented the wealthiest strata of society had monarchical ambitions.[26] Augustinas Voldemaras noted to a German envoy that the thoughts of a coup reached back as early as 1922.[27] The nationalists, using the fact that all commanders of military units were invited to Grinius's birthday, took control of military and civilian institutions, arresting Mykolas Sleževičius and Grinius.[28] According to Grinius's own memoirs, Povilas Plechavičius, one of the main instigators, became "dictator" not by his own choice.[29] Grinius promptly resigned to "save Lithuania from possible misfortunes".[30] Smetona and his party justified the coup by saying that a Communist takeover was imminent. According to Grinius's own memoirs, the claim was false.[31]

Post-political career

[edit]After the coup, Grinius continued working in the Kaunas city municipality, building the foundation for a healthcare system. On 6 December 1928, he was given a permanent pension of 1,200 Litai.[32] He continued his medical career by heading some health societies, editing the newspaper "Battle with Consumption" (Kova su džiova) and "Drop of Milk" (Pieno lašas), and translating fictional and scientific literature.[32] In a 1939 journal entitled Varpininkų kelias he wrote an article explaining the benefits of democratic society, that in the future Lithuania will be democratic, and that the citizens should elect a President directly rather than the parliament. In another journal he promoted non-violence against Lithuanian Jews.[33]

Occupation

[edit]During Soviet occupation, Grinius edited the newspaper Liaudies sveikata and headed the Kaunas Hygiene Museum. In 1942, during Nazi German occupation, Grinius, Konradas Aleksa, and Mykolas Krupavičius signed a memorandum for the German general commissar in Kaunas on the killing of Jews and colonization of Lithuania.[34] The authors of the memorandum were promptly arrested. Aleksa and Krupavičius were driven to Germany, while Grinius was deported to his home village of Selema.[35]

Emigration and last years

[edit]In 1944, with help from his family, Grinius emigrated to the West. His archive of photos, letters, etc. was destroyed in the process. He began writing his memoirs anew in a German displaced persons camp in Germany. Its first volume was published in 1947 in Tübingen. That same year he moved to the United States and collaborated with the Lithuanian émigré press. Grinius wrote to sixteen country leaders asking them for aid.

Grinius died on 4 June 1950 in Chicago.[5] His urn and remains were moved to Lithuania on 8 October 1994 and buried near Selema in Mondžgirė.[36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Dr. Kazys Grinius Dies; Ex-President of Lithuania". Evening Star. Washington, DC. 5 June 1950. p. 12. Retrieved 29 June 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f "Grinius, Former Lith President, Dies Here at 83". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, IL. 5 June 1950. p. 59. Retrieved 30 June 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Apdovanoti pasaulio tautų teisuoliai". www.jmuseum.lt (in Lithuanian). 21 October 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ "Col. Grinius Haed of Lithuanian National Council". The Lithuanian American Week. Chicago, IL. 10 April 1942. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved 1 July 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Kazys Grinius". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ Eidintas 1993.

- ^ "Jonas Grinius". vle.lt. MELC. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Grigaitytė, Laima (26 April 2018). "Onos Griniūtės-Bacevičienės prisiminimai I". msavaite.lt. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Ulevičius, Bonifacas. "Vytautas Bacevičius". vle.lt. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Knygnešys Kazys Grinius". spaudos.lt. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Čepas 1997, p. 221.

- ^ Grinius 2023, p. 9.

- ^ ""Šviesa"". vle.lt. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Čepas 1997, p. 246.

- ^ Žurnalistikos enciklopedija. Vilnius: Pradai. 1997. p. 156.

- ^ "Paminklai Lietuvos Knygnešiams". spaudos.lt. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Banevičius, Algirdas (1991). 111 Lietuvos valstybės 1918–1940 politikos veikėjų: enciklopedinis žinynas. Vilnius: Knyga. p. 63. ISBN 5-89942-585-7.

- ^ "Prezidento K.Griniaus pėdsakai Kaukaze". ausis.gf.vu.lt. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006.

- ^ Čepas 1997, p. 226.

- ^ Grinius 2023, p. 11.

- ^ Čepas 1997, p. 248.

- ^ Čepas 1997, p. 251.

- ^ "III Seimas (1926–1927)".

- ^ Jurgelaitis, Remigijus. "Tarpukario prezidentų palikuonys politikų dinastijos nepratęsė". kauno.diena.lt. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Eidintas 1993, p. 169.

- ^ Eidintas 1993, p. 149.

- ^ Eidintas 1993, p. 90.

- ^ Eidintas 1993, p. 93.

- ^ Eidintas 1993, p. 177.

- ^ Eidintas 1993, p. 180.

- ^ Grinius 2023, p. 14.

- ^ a b Grinius 2023, p. 12.

- ^ Čepas 1997, p. 253.

- ^ Aleksa, Valentinas. "Memorandumas vokiečių generaliniam komisarui Kaune". vle.lt. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ Čepas 1997, p. 254.

- ^ "Paminėtas prezidento Kazio Griniaus perlaidojimo 20-metis". marijampole.lt. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Eidintas, Alfonsas (1993). Kazys Grinius: ministras-pirmininkas ir prezidentas (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Mintis. ISBN 9785417005787.

- Čepas, Rimantas (1997). Lietuvos Respublikos Ministrai Pirmininkai (1918-1940) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Alma littera. ISBN 9986023793.

- Grinius, Kazys (2023). Sugadintas jubiliejus. Kazio Griniaus atsiminimai apie 1926 m. perversmą (in Lithuanian). Bonus Animus. ISBN 9789955754817.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch