Keith Hunter Jesperson

Keith Hunter Jesperson | |

|---|---|

Mug shot of Jesperson in December 2009 | |

| Born | 6 April 1955 Chilliwack, British Columbia, Canada |

| Height | 2.03 m (6 ft 8 in) |

| Spouse | Rose Hucke (m. 1975; div. 1990) |

| Children | 3 |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment (without parole) |

| Details | |

| Victims | 8 confirmed (confessed to as many as 160) |

Span of crimes | 21 January 1990 – 16 March 1995 |

| Country | U.S., Canada |

| State(s) | California, Florida, Nebraska, Oregon, Washington, Wyoming |

Date apprehended | 30 March 1995 |

| Imprisoned at | Oregon State Penitentiary |

Keith Hunter Jesperson (born April 6, 1955) is a Canadian-American serial killer who murdered at least eight women in the United States during the early 1990s. He was known as the Happy Face Killer because he drew smiley faces on his many letters to the media and authorities. Many of Jesperson's victims were sex workers and transients who had no connection to him. Strangulation was his preferred method of murdering, the same method he often used to kill animals as a child.

After the body of Jesperson's first victim, Taunja Bennett, was found, media attention surrounded Laverne Pavlinac, a woman who falsely confessed to Bennett's murder with the help of her abusive boyfriend, John Sosnovske. Upset that he was not getting any media attention, Jesperson drew a smiley face on a bathroom wall hundreds of miles from the scene of the Bennett killing and wrote an anonymous letter confessing to the murder, providing proof. When that did not elicit a response, he began writing letters to the media and authorities.

Jesperson's last murder was the crime that ultimately led to his capture. While he has claimed to have killed as many as 160 people, only eight murders have been confirmed. Jesperson is currently serving a sentence of life without parole at the Oregon State Penitentiary.

Early life

[edit]Keith Jesperson was born on 6 April 1955 to Leslie "Les" Samuel and Gladys Lorraine Jesperson (née Bellamy) in Chilliwack, British Columbia, Canada,[1] the middle child with two brothers and two sisters.[2] His father was a domineering alcoholic; according to Jesperson, his paternal grandfather was prone to violence. Jesperson's father denied being an abusive parent; however, other family members corroborated the abuse claims to author Jack Olsen.[3]

Treated like a black sheep by his own family, and teased by other children for his large size, Jesperson was a lonely child who showed a propensity for torturing and killing animals. After moving to Selah, Washington, United States, he had trouble fitting in and making friends, again because of his large size. Jesperson's brothers did not help him; instead they nicknamed him "Igor" or "Ig", a name that stuck throughout his school years.[4] Because of this, Jesperson was a shy child, content to play by himself much of the time. He would often get into trouble for misbehaving, sometimes violently, and would be severely punished by his father. This included beatings, sometimes with a belt in front of others, and in one case he received an electric shock.[1]

At a very early age—as young as five—Jesperson would capture and torture animals. He enjoyed watching animals kill each other as well as the feeling he got from taking their lives.[5] This continued as he grew older. Jesperson would capture birds and strays around the trailer park where he lived with his family, severely beating the animals and then strangling them to death, something for which he claims his father was proud of him. In the years following, Jesperson said he often thought about what it would be like to do the same to a human.[5]

That desire manifested in two attempted murders. The first occurred when Jesperson was around age 10, when he was friends with a boy named Martin. The two would often get into trouble together, and Jesperson claimed he was often punished many times for things Martin had done and shifted the blame. This led Jesperson to violently attack Martin until his father pulled him away. He later claimed his intention was to kill the boy.[6] Approximately one year later, Jesperson was swimming in a lake when another boy held him underwater until he blacked out. Sometime later, at a public pool, Jesperson attempted to drown the boy by holding his head under the water until a lifeguard pulled him away.[6]

Jesperson reported that he was raped at age 14.[6] He graduated from high school in 1973, but did not attend college because his father did not believe he could do it.[6] Although Jesperson was not successful with girls in high school, having never even attended a school dance or his prom, he did enter into a relationship after high school. In 1975, when Jesperson was aged 20, he married Rose Hucke, and the couple had three children: two daughters and one son. Jesperson worked as a truck driver to support the family.

Several years later, Hucke began to suspect Jesperson was having affairs when strange women would call. Tension in the marriage increased, and after fourteen years, while Jesperson was on the road, Hucke packed up her children and belongings and drove 200 miles (322 km) to live with her parents in Spokane, Washington.[7] Jesperson continued to spend time with his children when he was in town. The couple divorced in 1990.[8]

At age 35, standing 6 feet 7 inches (2.01 m) and weighing approximately 255 pounds (116 kg),[9] Jesperson began working toward the goal of joining the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), but an injury suffered while training ended this endeavor. He then sought work again as a truck driver after relocating to Cheney, Washington.[10] Jesperson soon realized that this job afforded him the opportunity to kill without being suspected.

Victims

[edit]

Jesperson's first known victim was Taunja Bennett on 21 January 1990, near Portland, Oregon, United States. He introduced himself to Bennett at a bar and invited her to a house he was renting. After getting in an argument with Bennett, he strangled her to death with his hands and disposed of her body.

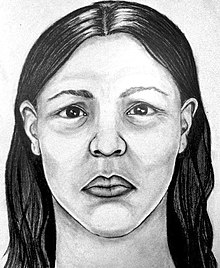

On 30 August 1992, the currently-unidentified body of a woman Jesperson had raped and strangled was found near Blythe, California, United States.[11] Jesperson gives the Jane Doe's name as Claudia. A month later, in Turlock, California, the body of Cynthia Lyn Rose was discovered. Jesperson claims Rose was a sex worker who entered his truck at a truck stop while he slept. His fourth victim was another sex worker, Laurie Ann Pentland of Salem, Oregon, whose body was found in November 1992. According to Jesperson, Pentland attempted to double the fee she charged for the sex he had been engaged in with her. She threatened to call the police, and he strangled her.

Jesperson killed his next victim in June 1993 in Santa Nella, California. She was a previously unidentified woman named Patricia Skiple,[12] who, he claimed, was named "Carla" or "Cindy".[13] Police originally considered her death a drug overdose. In September 1994, another Jane Doe was found in Crestview, Florida. Jesperson had previously said that her name was Suzanne,[10][14] and she was identified as Suzanne L. Kjellenberg on October 3, 2023.[15]

Jesperson was arrested on 30 March 1995 for the murder of Julie Winningham. He had been questioned by police a week before, but they had no grounds to arrest him after he refused to talk. In the days following, Jesperson decided that he was certainly going to be arrested, and after two suicide attempts turned himself in hoping it would result in leniency during his sentencing. While in custody, Jesperson began revealing details of his killings and making claims of many others, most of which he later recanted. A few days before his arrest, he wrote a letter to his brother in which he confessed to having killed eight people over the course of five years. This led police agencies in several states to reopen old cases, many of which were found to be possible victims of Jesperson.[16]

Although Jesperson at one point claimed to have had as many as 160 victims,[17] only the eight women killed in Washington, Oregon, California, Florida, Nebraska, and Wyoming have been confirmed. He is serving three consecutive life sentences at the Oregon State Penitentiary in Salem. In September 2009, Jesperson was indicted in Riverside County, California, on murder charges; he was extradited in December 2009.[18] He was convicted of another murder and received a fourth life sentence in January 2010.[19]

Laverne Pavlinac

[edit]Early in the investigation of Bennett's murder, Laverne Pavlinac read the news reports surrounding Bennett's death and saw it as an opportunity to force an end to the long-term abusive relationship she had been in with her live-in boyfriend, John Sosnovske. Pavlinac set up a meeting with investigators and gave a false confession, using the details she had read in the newspaper to give a detailed story of how Sosnovske forced her to help him rape, murder, and dispose of Bennett's body. Pavlinac and Sosnovske were both arrested on 5 March 1990 and both were convicted of the murder on 8 February 1991.[20] To avoid the possibility of facing the death penalty, Sosnovske pleaded no contest. He was sentenced to life in prison while Pavlinac was sentenced to no less than ten years, much more than she had anticipated. Pavlinac soon admitted to making up her entire story, but her claims were ignored.[21]

On 7 January 1996, more than five years after their conviction, Pavlinac and Sosnovske were released from prison after Jesperson and his attorney offered his confession with convincing evidence of his guilt. He had given police officers the location of the victim's purse. The purse had not been found at the crime scene, and its location was considered information only the killer would know.[22]

"The Happy Face Killer"

[edit]Following Bennett's murder, as all the attention was going to Pavlinac and Sosnovske, Jesperson wrote a confession on the bathroom wall of a truck stop and signed it with a smiley face. When that did not create the attention he desired, he wrote letters to media outlets and police departments confessing to his murders, starting with a six-page letter to The Oregonian in which he revealed the details of his killings. Jesperson signed each letter with a smiley face.[8][17] This led Phil Stanford, the journalist working the story for The Oregonian, to dub Jesperson "The Happy Face Killer".[8]

Jesperson's daughter

[edit]In November 2008, Jesperson's daughter, Melissa G. Moore, appeared on Dr. Phil to talk about her father.[23] She was also featured on The Oprah Winfrey Show,[24] the Lifetime Movies network series Monster in My Family,[25][26] and a 20/20 special on ABC.[7] She was a correspondent for Crime Watch Daily.[27]

In 2008, Moore published a book titled Shattered Silence: The Untold Story of a Serial Killer's Daughter. Moore recounts living with Jesperson until her parents' 1990 divorce, and noticing how her father was different when she was in elementary school. Their house bordered an apple orchard, and Jesperson killed stray cats and gophers that wandered nearby. One day, she watched, horrified, as he hung stray kittens from the family's clothesline. She ran to get her mother, and when they returned, the kittens lay on the ground dead.[7] He had watched and laughed as the kittens clawed each other to escape, then he killed them.[28] In November 2014, she wrote an article about her father for the BBC.[29]

In March 2018, she was featured in an episode, titled "Put on a Happy Face", of the Investigation Discovery true crime series Evil Lives Here.[30][31] In September 2018, podcast network HowStuffWorks began releasing a show called Happy Face[32] featuring interviews with Melissa about her childhood and her father.[33] The series had 12 episodes.

In June 2021, a trailer appeared on iTunes for a new true crime podcast called Life After Happy Face, to be hosted by Melissa Moore and forensic criminologist Laura Pettler.[34] The episode was released on July 9, 2021.

An eight episode TV series based on her podcast is set to stream on Paramount+ in 2025.[35]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Kreuger, Justice, & Hunt, p. 1

- ^ Olsen, [page needed]

- ^ Olsen, pp. 35, 334

- ^ Olsen, p. 141

- ^ a b King, p. 5

- ^ a b c d Kreuger, Justice, & Hunt, p. 2

- ^ a b c "Daughter", p. 1

- ^ a b c "Daughter", p. 2.

- ^ King, p. 1

- ^ a b King, p. 3

- ^ "The National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs)". NamUs.gov. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "'Happy Face Killer' Bay Area murder victim finally identified". SF Gate. 18 April 2022. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ "Case File 497UFCA". doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Kreuger, Justice, & Hunt, p. 3

- ^ "District 1 Medical Examiner's Office & Okaloosa County Sheriff's Office Teams with Othram to Identify a 1994 Homicide Victim". DNASolves. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- ^ King, p. 4

- ^ a b Grollmus, Denise (22 December 2009). "'Happy Face Killer' Keith Hunter Jesperson Racks Up More Victims". True Crime Report. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ Russel, Michael (10 December 2009). "'Happy Face Killer' extradited to Southern Calif. to face charges". The Oregonian. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ^ "Serial killer receives fourth life sentence". The San Diego Union-Tribune. 10 January 2010.

- ^ Moore & Cook, p. 80

- ^ King, p. 2

- ^ Moore & Cook, p. 67

- ^ Moore & Cook, p. 212

- ^ "Dr. Phil Returns to The Oprah Show: My Father Is a Serial Killer". Oprah.com. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ Reyes, Traciy (10 July 2015). "ABC '20/20': Melissa Moore, Daughter Of Serial Killer, Opens Up Tonight About Life With 'Happy Face Killer' Keith Jesperson". Inquisitr. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ Butler, Karen (3 June 2015). "'Monster in My Family' connects serial killers' relatives with victims' families". United Press International. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "Meet Crime Watch Daily Correspondent Melissa Moore | Truecrimedaily.com". Crime Watch Daily. 1 October 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ Moore & Cook, p. 4

- ^ "My evil dad: Life as a serial killer's daughter". BBC News. 3 November 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ "Evil Lives Here | Put on a Happy Face". imdb.com. 18 March 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ "Evil Lives Here | Put on a Happy Face". TVGuide.com. CBS Interactive Inc. 18 March 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ "Happy Face Presents: Two Face on Apple Podcasts". iTunes. 18 August 2020.

- ^ Barcella, Laura (10 January 2019). "True Crime Podcast: 'Happy Face'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ "Life After Happy Face on Apple Podcasts". Apple Podcasts.

- ^ Petski, Denise (9 May 2024). "Happy Face Adds Damon Gupton & Momona Tamada As Recurring". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Moore, Melissa G. & M. Bridget Cook (2009). Shattered Silence: The Untold Story of the Daughter of a Serial Killer. Cedar Fort. ISBN 978-1-59955-238-5.

- Olsen, Jack (2002). I: the creation of a serial killer. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-24198-8.

External links

[edit]- "Daughter of the 'Happy Face Killer' Talks About Growing Up With a Serial Killer Dad". ABC News 20/20. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- King, Gary C. "Keith Hunter Jesperson". truTV Crime Library. Retrieved on 21 August 2010.

- Kreuger, Peggy; Kendra Justice & Amy Hunt (March 2006). "Keith Hunter Jesperson: Happy Face Killer" (PDF). Radford University Department of Psychology. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- Daughter of serial killer confronts her past, Seattle Times

- My life as a serial killer’s daughter, BBC News

- Radio Interview with Melissa Moore (daughter)

- Stuff They Don't Want You To Know

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch