Laquintasaura

| Laquintasaura Temporal range: Early Jurassic, Hettangian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstruction of Laquintasaura venezuelae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Genus: | †Laquintasaura Barrett et al., 2014 |

| Species: | †L. venezuelae |

| Binomial name | |

| †Laquintasaura venezuelae | |

Laquintasaura is a genus of Venezuelan ornithischian dinosaur containing only the type species Laquintasaura venezuelae. It is known for being one of the most primitive ornithischians in the fossil record, as well as the first dinosaur to have been identified from Venezuela. The name is derived from the La Quinta Formation, where it was discovered, and the feminine Greek suffix for lizard, with the specific name referring to the country of Venezuela. It is known from hundreds of fossil elements, all derived from a single extensive bonebed locality. Initially discovered by French palaeontologists, numerous expeditions have been conducted to excavate from the bonebed, largely led by Marcelo R Sánchez-Villagra. Once thought to represent remains of Lesothosaurus, it was formally named in a 2014 study; much of the abundant material was not yet prepared at the time and research remains ongoing.

A small animal, it is thought to have been a lightly built and would not have grown much larger than 1 metre (3.3 ft) in length. One of the first species known to possess the distinctive bird-like hip bone of ornithischians, it would have been a capable bipedal runner. Showcasing rather primitive anatomy overall, its most noted characteristics are found in its teeth. Unlike the leaf shaped teeth of related ornithschians, those of Laquintasaura had a distinctive triangular shape, with distinct striations and sharp denticles running down the edges. These may have contributed to an omnivorous diet unlike those of later relatives. They would have lived in groups, living on a seasonal alluvial plain and being preyed upon by the contemporary Tachiraptor.

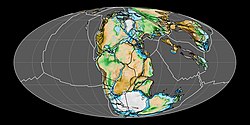

Taxonomic uncertainty has led to conflicting hypotheses that it is either an early diverging ornithischian or part of the subgroup Thyreophora. Aspects of its femoral anatomy, possessing only some traits of later relatives, may be demonstrative of an important transitional step in the evolution from earlier types of dinosaur. Regardless of its precise classification, its dating to around 200 million years ago at the start of the Jurassic and primitive nature make it a key insight into early ornithischian evolution. Likewise, its discovery was considered significant to the understanding of the geographical distribution of early dinosaurs on the supercontinent of Pangaea. Previous research had cast doubt on whether dinosaurs lived around the equator during their early evolution, and on when ornithischians first spread to the northern Hemisphere; the discovery of Laquintasaura demonstrated both at a very early point in time.

Discovery and naming

[edit]

Laquintasaura is known from a single locality, a bonebed in rocks of the La Quinta Formation, which is Early Jurassic in age. This bonebed was first discovered in the 1980s by a team of French palaeontologists on a reconnaissance mission to Venezuela, near a road between the towns of La Grita and Seboruco, in the state of Táchira. Initially, the French team discovered two teeth and the fragment of a quadrate (a bone at the back of the skull, articulating with the jaw). These fossils were brought to Paris, with intent to return the material to Venezuela after study, and described by D.E. Russel and colleagues in a 1992 publication. Based on similar cranial anatomy, they were tentatively referred to the genus Lesothosaurus but not to any specific species; this genus, also from the Early Jurassic, is found in South Africa and Lesotho. Unaware of the French team's discoveries, Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra and colleagues conducted their own expeditions into the La Quinta Formation in 1992 and 1993 following an initial survey in 1989. While they did not find vertebrate fossils during the 1989 trip, they rediscovered the bonebed during the later expeditions; dinosaur expert James Clark is credited with noticing the locality. A few plaster jackets worth of fossils were recovered and transported to Buenos Aires in Argentina, where Sánchez-Villagra and the team of Guillermo Rougier spent three months partially preparing the fossils. The fossils were then returned to Venezuela, being brought to Universidad Simón Bolívar. Several years later in the late 1990s, Sánchez-Villagra would become aware of the French specimens, which had remained in Paris, and co-ordinate their return to Venezuela as well. They were deposited in the collections of the Museu de Biología de la Universidad de Zulia (MBLUZ).[1]

Soon after the transfer of material to the Universidad Simón Bolívar, Sánchez-Villagra became aware he was no longer permitted to study it there. He resolved to conduct expeditions to find additional material. The Universidad Simón Bolívar material has gone unstudied since. A successful trip was organized in December 1993 with a new team from Caracas, which produced abundant new material. This was deposited in the MBLUZ, like the original French material. Early preparation of these blocks was reported on at the 1994 conference of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. Sánchez-Villagra and Fernando Novas, who had met during the preparation in Buenos Aires, obtained a grant from the Jurassic Foundation to study this material. The project would eventually become based in the Natural History Museum in London, England, and would bring in Paul Barrett.[1] He, Novas, Sánchez-Villagra, and colleagues described the material in a 2008 paper, identifying a likely new genus of ornithischian among many other indeterminate animals but not naming it until additional material was known.[1][2]

This additional material was described in a 2014 paper by a team including Barrett and Sánchez-Villagra. Through comparisons using newly prepared material as well as new data on the usefulness of identifying features relied on by the 2008 study, it was found that almost all material in the bonebed in fact belonged to the previously identified ornithischian taxon. With the entire wealth of material now recognized as belonging to the taxon, they formally named it as Laquintasaura venezuelae. The generic name derives from the name of the geologic formation and the feminine Greek suffix for lizard; the specific name refers to the country and people of Venezuela. Among the material, the isolated tooth MBLUZ P.1396 was designated as the holotype, forming the type series with paratypes MBLUZ P.5017, a partial femur; MBLUZ P.5018, a partial left ischium; and MBLUZ P.5005, a left astragalocalcaneum. Though the choice of a tooth as the type specimen is uncommon for a dinosaur, it was chosen due to being the most distinctive aspect of the anatomy, being a very abundant element of the sample, and the unlikelihood that teeth would be different across sections of the mouth due to the uniformity of the known teeth in related taxa.[3] A later 2021 study by Carlos-Manuel Herrera-Castillo, Sánchez-Villagra, and colleagues described a premaxilla that has been prepared and studied since the 2014 paper; at the time of this publication, study and preparation of much material remains ongoing.[1] As it is the oldest reliably dated ornithischian, hailing from the very start of the Jurassic, its discovery is considered to very significant.[1][3]

Hundreds of individual fossil elements are known for Laquintasaura, representing a minimum of four individuals and potentially many more. Material that had already been prepared upon publication of the 2014 paper included isolated cranial remains, an abundance of teeth, cervical, dorsal, sacral, and caudal vertebrae, a scapula, pelvic and hindlimb material, and other isolated postcranial elements. Forelimb material was completely absent, and material from the feet was very limited. Much of the material was still unprepared at this time, and it is possible that much more material remains ungathered from the bonebed.[3] Isolated theropod remains were also reported from the bonebed, some of which was later described as Tachiraptor; sauropod material was also later identified.[1][4] Dental morphotypes similar to that of Laquintasaura have been described from the Kota Formation in India as well as from the White Limestone Formation in England. They date to the Bathonian age of the Middle Jurassic, more than 30 million years after Laquintasaura lived.[5][6]

Description

[edit]

Like other early members of Ornithischia, it is assumed that Laquintasaura was a lithe bipedal animal. The largest femur among the bonebed is 90 millimetres (3.5 in) in length; assuming similar proportions to similar animals like Hypsilophodon, Heterodontosaurus, and Hexinlusaurus, it was estimated the Laquintasaura individual could grow to around 1 metre (3.3 ft) in length. However, this individual was a subadult, and more fragmentary remains appear to belong to slightly larger animals. The small size and conservative skeletal anatomy of Laquintasaura indicates it had not yet diversified extensively from their ancestral anatomical state. Only later would ornithischians diverge into larger, more specialized animals with traits like armor and quadrupedality.[3]

The most distinctive anatomy of Laquintasaura is found in its dentition. The teeth are unusually tall and have their widest point immediately above the tooth root; the result of this is an isoceles triangle shape. Coarse denticles run along the entire crown margin (the edge of the exposed tooth). By comparison, the teeth of other primitive ornithischians have a stouter, sub-triangular shape that continues to widen farther up the tooth and only possesses denticles along the top of the crown. Additionally, the teeth of Laquintasaura possess uniquely prominent striations on both the inside and outside sides of the tooth. As opposed to the heterodont condition of later ornithischians, this dental anatomy is thought to have been uniform throughout the entirety of the mouth, both in the premaxilla and the maxilla. Some teeth are, however, somewhat more recurved than others.[3] Convergently similar anatomy, with a tall tooth construction and striations, does occur convergently in the neornithischian dinosaur Hexinlusaurus, which nonetheless has a differing tooth shape and denticulation.[3][6] The premaxilla of L. venezuelae has seven teeth in each position and does not present a diastema close to the premaxillo-maxillary suture. Such a high number of premaxillary teeth is uncommon in ornithischians, outside of some members of Ankylosauria. The high count in Laquintasaura elucidates the basal evolution state of Ornithischia, and indicates the species' dental anatomy is very primitive even compared to other Early Jurassic taxa.[1]

Though less distinctive than the dentition, the postcranium also possesses distinguishing traits. The upper surface of the ischium further up than the obturator process is highly inflected; in closely related taxa both sides of the ischium form a more continuous, smooth surface. The epicondyle at the connection of the femur and the fibula is inset in the middle from a ventral or posterior view, a derived trait lacking in other primitive taxa, which possess a smooth transition without any notch forming a "step". Finally, the astragalus has a broad and deep U-shaped notch on its top surface; a similar V-shaped notch is seen in Scutellosaurus, but is less than half as deep. In contrast to these unique traits, ornithischian synapomorphies can be seen in the pelvic anatomy. In addition to its diagnostic features, numerous differences from other individual basal ornithischian taxa were noted, described in detail in the supplementary material of the 2014 description paper.[3] A later 2022 study by David Norman and colleagues concerning ornithischian evolution noted features not described in the initial publication. They brought attention to the backward-pointing pubis, as Laquintasaura is the oldest known ornithischian with this trait, which has traditionally been considered a key identifier of the origin of Ornithischia alongside the evolution of the predentary bone, unpreserved in Laquintasaura. Furthermore, they noted its femoral anatomy may be intermediate to that of Triassic silesaurs and Jurassic ornithischians. Its fourth trochanter is wider and lacking in protrusion than other Jurassic taxa, but is more strongly developed than the shallow crest seen in silesaurs. Similarly, the head of the femur has flat shape as in silesaurs (strongly rounded in other taxa), but projects inwards relative to the femoral shaft as in Jurassic species.[7]

Classification

[edit]

The phylogenetic relationships of Laquintasaura remains somewhat uncertain.[8][9][10] It is robustly considered a basal member of the group Ornithischia, but its exact position within this clade are unresolved. The original 2014 description found it in a large polytomy with Eocursor, Lesothosaurus, Stormbergia, Scutellosaurus, the clade Thyreophora, and the clade Neornithischia.[3] Some later phylogenetic analyses have had to remove the taxon from phylogenetic analyses outright due to being too fragmentary and lowering the resolution of the results.[11][12] Some studies, such as that of Matthew G. Baron and David Norman or that of Thomas J. Raven and Susannah Maidment, both in 2017, have found it to be a very early member of the group Thyreophora (armored dinosaurs), as the sister taxon of Scutellosaurus.[13][14] Bone histology, similar to Scutellosaurus but unlike Lesothosaurus, has been posited as circumstantial evidence of this placement.[15] The analysis of a study on ornithischian phylogeny by P. E. Dieudonné and colleagues in 2021 instead found Laquintasaura in a more primitive position outside of the clade Genasauria.[16] Similarly, a 2022 study by Baron, Norman, and colleagues found it to be outside of the clade Prionodontia (known Saphornithischia under alternative nomenclatural schemes[17]), intermediate between the traditional scope of Ornithischia and a grade of animals that traditionally compose Silesauridae.[7] A comprehensive study on the classification of early ornithischians by André Fonseca and colleagues found positions within Thyreophora and outside of Genasauria to be plausible, and highlighted the fact the taxon has only received a preliminary description as a factor in its instability.[17]

The cladogram from Baron et al. (2017) is shown immediately below, and that of Norman et al. (2022) is shown at the bottom. Clade names have been inserted based on definitions established by a paper by Daniel Madzia and colleagues in 2021 for clarity.[13][16][18]

Palaeobiology

[edit]The bone histology of Laquintasaura was studied by Paul Barret and colleagues in 2014, as this could potentially inform on its physiology in life. Six cross-sections of bone were taken from five different specimens, consisting of material from a scapula, tibia, a femur, a rib, and a long bone of uncertain affinity. Each of these bones were analyzed for indications of age at death; most of the material was found to belong to subadult individual who had not reached skeletal maturity. Based on the presence of only two annuli, growth indicating rings, it was determined that the tibia likely belong to a juvenile around three years old. Contrastingly, the presence of at least nine tightly spaced lines of arrested growth and extensive bone remodelling in the scapula indicated it belonged to a mature adult, likely around ten to twelve years of age. It was noted that all of the specimens lack fibrolamellar bone tissue, associated with high growth rates in ornithischians such as Lesothosaurus, ornithopods, and marginocephalians. This is similar to small thyreophorans like Scutellosaurus, and was suggested to indicate a possible secondary reversal to slower growth relative to ancestral taxa. However, due to the lack of data on ornithischian histology as a whole, as well as the limited sample size available to confirm the lack of that tissue organization in Laquintasaura, these conclusions remain uncertain.[3]

Palaeoecology

[edit]

Laquintasaura hails from the La Quinta Formation in what is now Colombia and Venezuela, found in the Venezuelan part of the formation.[3][19] The exact age of the La Quinta Formation was traditionally very unclear, but modern estimates find that the section containing the Laquintasaura bonebed dates to the Hettangian age of the Early Jurassic epoch, around 200 million years ago and potentially as little as one hundred and fifty thousand years from the end of the Triassic period.[4][3][20] This very old age makes Laquintasaura one of the earliest known members of Ornithischia, making it important to understanding their early evolution.[1][3] It provides concrete evidence that they had spread to the northern hemisphere by the start of the Jurassic,[9] and its geographic placement in an equatorial region demonstrates early dinosaur presence in equatorial latitudes, as well as such region's role in early dinosaur evolution, something traditionally doubted.[1][3][21] Though the genus' presence so soon after the end-Triassic extinction indicates ornithischians achieved quick expansion in diversity and distribution, its conservative anatomy indicates that increases in body size and anatomical specialization did not occur until later in the Jurassic.[3]

The ecosystem that Laquintasaura lived in is thought to represent an alluvial plain, with both arid and humid seasons.[4] The early theropod dinosaur Tachiraptor would have lived alongside Laquintasaura, and likely preyed upon it.[4][22] The sauropod dinosaur Perijasaurus also hails from the La Quinta Formation, but is thought to have lived at a later time near the end of the Early Jurassic, around 175 million years ago.[19] Laquintasaura is thought to have been primarily herbivorous, but the unusually tall structure of the teeth are reminiscent of carnivorous animals, indicating they may have also eaten things like small insects as part of their diet.[21][23] Similar omnivorous behaviour has been suggested in the fellow primitive ornithischian Lesothosaurus,[24] as well as more tentatively in taxa like Agilisaurus, Hypsilophodon, and Orodromeus before disappearing in more derived relatives such as iguanodontians.[25]

The taphonomy of the Laquintasaura bonebed remains incompletely studied. The remains are thought to have undergone some degree of low-energy transport, but the lack of any damage to the bones, or signs of plant root damage or insect boring holes, indicate the remains were not exposed for a long time prior to burial.[3] The bonebed is entirely devoid of microfossils, invertebrates, or plant remains, and is palynologically barren; the only other animal found at the site is the scant remains of Tachiraptor.[4][3] All of this indicates the four or more individuals at the site likely died together and maybe have lived together in life, indicative of social behaviour. Herding is known in ornithischians of the Late Jurassic and Cretaceous, but its presence in Laquintasaura would be the first recognized in such an early member of the group (though more recent research has also indicated presence in the genus Lesothosaurus).[3][15]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Herrera-Castillo, Carlos M.; Carrillo-Briceño, Jorge D.; Sánchez-Villagra, Marcelo R. (2021). "Non-invasive imaging reveals new cranial element of the basal ornithischian dinosaur Laquintasaura venezuelae, Early Jurassic of Venezuela". Anartia. 32: 53–60. doi:10.5281/zenodo.5571307. Archived from the original on 2024-08-14. Retrieved 2024-09-30.

- ^ Barret, Paul M.; Butlet, Richard J.; Moore-Fay, Scott C.; Novas, Fernando E.; Moody, John M.; Clark, James M.; Sänchez-Villagra, Marcelo R. (2008). "Dinosaur remains from the La Quinta Formation (Lower or Middle Jurassic) of the Venezuelan Andes". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 82 (2): 163–177. Bibcode:2008PalZ...82..163B. doi:10.1007/bf02988407. Archived from the original on 2024-07-09. Retrieved 2024-07-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Barrett, Paul M.; Butler, Richard J.; Mundil, Roland; Scheyer, Torsten M.; Irmis, Randall B.; Sánchez-Villagra, Marcelo R. (6 August 2014). "A palaeoequatorial ornithischian and new constraints on early dinosaur diversification". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 281 (1791). Royal Society: 20141147. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.1147. PMC 4132680. PMID 25100698.

- ^ a b c d e Langer, Max C.; Rincón, Ascanio D.; Ramezani, Jahandar; Solórzano, Andrés; Rauhut, Oliver W.M. (8 October 2014). "New dinosaur (Theropoda, stem-Averostra) from the earliest Jurassic of the La Quinta formation, Venezuelan Andes". Royal Society Open Science. 1 (2). Royal Society: 140–184. Bibcode:2014RSOS....140184L. doi:10.1098/rsos.140184. PMC 4448901. PMID 26064540.

- ^ Wills, Simon; Underwood, Charlie J.; Barrett, Paul M. (2024). "A hidden diversity of ornithischian dinosaurs: U.K. Middle Jurassic microvertebrate faunas shed light on a poorly represented period". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 43 (5). doi:10.1080/02724634.2024.2323646. Archived from the original on 2024-06-26. Retrieved 2024-06-26.

- ^ a b Prasad, Guntupalli V. R.; Parmar, Varun (2020). "First ornithischian and theropod dinosaur teeth from the Middle Jurassic Kota Formation of India: paleobiogeographic relationships". In Guntupalli V. R. Prasad; Rajeev Patnaik (eds.). Biological Consequences of Plate Tectonics: New Perspectives on Post-Gondwana Break-up–A Tribute to Ashok Sahni. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland. pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-3-030-49752-1.

- ^ a b Norman, David B.; Baron, Matthew G.; Garcia, Mauricio S.; Müller, Rodrigo Temp (2022). "Taxonomic, palaeobiological and evolutionary implications of a phylogenetic hypothesis for Ornithischia (Archosauria: Dinosauria)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 196 (4): 1273–1309. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlac062. Archived from the original on 2022-12-13. Retrieved 2024-06-26.

- ^ Yao, X.; Barrett, P. M.; Lei, Y.; Xu, X.; Bi, S. (2022-03-15). "A new early-branching armoured dinosaur from the Lower Jurassic of southwestern China". eLife. 11: e75248. doi:10.7554/eLife.75248. PMC 8929930. PMID 35289749.

- ^ a b Breeden III, Bejamin T.; Rowe, Timothy B. (2020). "New Specimens of Scutellosaurus Lawleri Colbert, 1981, from the Lower Jurassic Kayenta Formation in Arizona Elucidate the Early Evolution of Thyreophoran Dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (4): e1791894. Bibcode:2021HBio...33.2335D. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1793979. Archived from the original on 2022-11-20. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ Breeden III, Benjamin T.; Raven, Thomas J.; Butler, Richard J.; Rowe, Timothy B.; Maidment, Susannah C. R. (2021). "The anatomy and palaeobiology of the early armoured dinosaur Scutellosaurus lawleri (Ornithischia: Thyreophora) from the Kayenta Formation (Lower Jurassic) of Arizona". Royal Society Open Science. 8 (7). Bibcode:2021RSOS....801676B. doi:10.1098/rsos.201676. PMC 8292774. PMID 34295511.

- ^ Han, Fenglu; Forster, Catherine A.; Xu, Xing; Clark, James M. (2017). "Postcranial anatomy of Yinlong downsi (Dinosauria: Ceratopsia) from the Upper Jurassic Shishugou Formation of China and the phylogeny of basal ornithischians". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 16 (14): 1159–1187. doi:10.1080/14772019.2017.1369185. S2CID 90051025.

- ^ Yang, Y.; Wu, W.; Dieudonné, P.; Godefroit, P. (2020). "A new basal ornithopod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of China". PeerJ. 8: e9832. doi:10.7717/peerj.9832. PMC 7485509. PMID 33194351.

- ^ a b Baron, Matthew G.; Norman, David B.; Barrett, Paul M. (2017-01-01). "Postcranial anatomy of Lesothosaurus diagnosticus (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Lower Jurassic of southern Africa: implications for basal ornithischian taxonomy and systematics". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 179 (1): 125–168. doi:10.1111/zoj.12434. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Raven, T.j.; Maidment, S.C.R. (2017). "A new phylogeny of Stegosauria (Dinosauria, Ornithischia)" (PDF). Palaeontology. 2017 (3): 401–408. Bibcode:2017Palgy..60..401R. doi:10.1111/pala.12291. hdl:10044/1/45349. S2CID 55613546. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-08-19. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ a b Botha, Jennifer; Choiniere, Jonah N.; Barrett, Paul M. (2022). "Osteohistology and taphonomy support social aggregation in the early ornithischian dinosaur Lesothosaurus diagnosticus". Palaeontology. 65 (4): e12619. Bibcode:2022Palgy..6512619B. doi:10.1111/pala.12619. Archived from the original on 2022-11-20. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ a b Dieudonné, P.E.; Cruzado-Caballero, P.; Godefroit, P.; Tortosa, T. (2021). "A new phylogeny of cerapodan dinosaurs". Historical Biology. 33 (10): 2335–2355. Bibcode:2021HBio...33.2335D. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1793979.

- ^ a b Fonseca, A.O.; Reid, I.J.; Venner, A.; Duncan, R.J.; Garcia, M.S.; Müller, R.T. (2024). "A comprehensive phylogenetic analysis on early ornithischian evolution". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 22 (1): 2346577. Bibcode:2024JSPal..2246577F. doi:10.1080/14772019.2024.2346577. Archived from the original on 2024-12-03. Retrieved 2024-09-30.

- ^ Madzia, D.; Arbour, V.M.; Boyd, C.A.; Farke, A.A.; Cruzado-Caballero, P.; Evans, D.C. (2021). "The phylogenetic nomenclature of ornithischian dinosaurs". PeerJ. 9: e12362. doi:10.7717/peerj.12362. PMC 8667728. PMID 34966571.

- ^ a b Rincón, Aldo F.; Raad Pájaro, Daniel A.; Jiménez Velandia, Harold F.; Ezcurra, Martín D.; Wilson Mantilla, Jeffrey A. (2022). "A sauropod from the Lower Jurassic La Quinta Formation (Dept. Cesar, Colombia) and the initial diversification of eusauropods at low latitudes". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 42 (1): e2077112. Bibcode:2022JVPal..42E7112R. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.2077112. Archived from the original on 2023-10-05. Retrieved 2024-09-30.

- ^ Irmis, Randall B.; Mundil, Roland; Mancuso, Adriana Cecilia; Carrillo-Briceño, Jorge D.; Ottone, Eduardo; Marsicano, Caudia A. (2022). "South American Triassic geochronology: Constraints and uncertainties for the tempo of Gondwanan non-marine vertebrate evolution". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 116: 10.1016/j.jsames.2022.103770. Bibcode:2022JSAES.11603770I. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2022.103770.

- ^ a b "New dinosaur discovered in Venezuela". Royal Society. 6 August 2014. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Tachiraptor admirabilis: New Carnivorous Dinosaur Unearthed in Venezuela". Sci-News. 10 October 2014. Archived from the original on 20 November 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Charles Q. Choi (6 August 2014). "New Fox-Sized Dinosaur Unearthed In Venezuela". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Sciscio, Lara; Knoll, Fabien; Bordy, Emese M.; Kock, Michiel O. de; Redelstorff, Ragna (2017-03-01). "Digital reconstruction of the mandible of an adult Lesothosaurus diagnosticus with insight into the tooth replacement process and diet". PeerJ. 5: e3054. doi:10.7717/peerj.3054. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5335715. PMID 28265518.

- ^ Hübner, Tom R.; Rauhut, Oliver W.M. (2010). "A juvenile skull of Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki (Ornithischia: Iguanodontia), and implications for cranial ontogeny, phylogeny, and taxonomy in ornithopod dinosaurs". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 160 (2): 366–396. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00620.x.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch