Continental Freemasonry

| Part of a series on |

| Freemasonry |

|---|

|

Liberal Freemasonry,[1][2] also known as Continental Freemasonry[3] or Adogmatic Freemasonry,[4][5] is a major philosophical tradition within Freemasonry that emphasizes absolute freedom of conscience, philosophical inquiry, and progressive social values.[6] Liberal Freemasonry is characterized by its acceptance of all people regardless of religious belief, gender, or philosophical outlook. It represents one of the two main branches of modern Freemasonry, alongside Conservative (Anglo-American) Freemasonry. The Liberal tradition emerged primarily in France during the Age of Enlightenment and came to full expression through the Grand Orient de France's 1877 adoption of absolute freedom of conscience as a founding principle. Today, Liberal Freemasonry is the predominant form of Freemasonry in Continental Europe, Latin America, and parts of Africa, with millions of members worldwide organized in various grand lodges and masonic bodies.[7]

History

[edit]Early Origins and Development (1725-1773)

[edit]

Liberal Freemasonry's distinct character began emerging from the Premiere Grand Lodge Ritual practiced in France during the Age of Enlightenment. The first documented French masonic lodge was established in Paris in 1725, and by 1773, the Grand Orient de France was formally established. These early French lodges operated differently from their English counterparts, placing greater emphasis on philosophical discourse and progressive thinking. French masonic lodges became important centers of intellectual exchange where nobles, philosophers, and merchants could meet as equals to discuss ideas. This egalitarian approach reflected Enlightenment values and would become a defining characteristic of Liberal Freemasonry.[8]

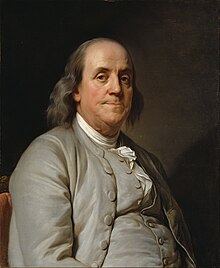

French lodges quickly became centers of Enlightenment thought, attracting philosophers, scientists, and intellectuals. Notable figures like Montesquieu,[9] Voltaire,[10] Lafayette,[11] Benjamin Franklin[12] and many other historical figures would find in these lodges spaces for free intellectual discourse.[13]

The formation of the Grand Orient de France in 1773 marked a crucial milestone. Under the leadership of the Duke of Montmorency-Luxembourg, the new organization established principles of democratic governance that were revolutionary for their time - each lodge would have an equal vote in organizational matters, and lodge masters would be elected rather than appointed.[14]

Revolutionary Period (1789-1815)

[edit]During the French Revolution, masonic lodges served as crucibles for democratic ideas. The revolutionary motto "Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité" while still being debated amongst scholars, probably originated in masonic discourse and Lodges before becoming the rallying cry of the Revolution then the official motto of France and Haiti.[15][16][17]

Many key revolutionary figures were Freemasons, including Mirabeau,[18] Lafayette, and later while never officially confirmed, Napoleon Bonaparte was also probably made a Freemason and most of his surroundings were confirmed Freemasons.[19][20] However, this period also saw significant challenges. During the Reign of Terror (1793-1794), many lodges suspended their activities to protect their members. Some prominent masonic leaders, including Philippe Égalité (formerly Grand Master of the Grand Orient), were executed despite their revolutionary credentials.[21]

Under Napoleon's rule (1799-1815), Freemasonry experienced both protection and control. While the emperor's brother Joseph Bonaparte served as Grand Master of the Grand Orient, this period saw attempts to use masonic networks for state purposes. Nevertheless, Liberal Freemasonry maintained its philosophical independence, continuing to advocate for progressive social reforms.[22]

The Louisiana Incident and Racial Equality (1868-1869)

[edit]The first major schism between Liberal and Conservative Freemasonry occurred in the United States, centered on racial equality. In 1868, the Grand Orient de France recognized the legitimacy of a racially integrated lodge in Louisiana, directly challenging the racist policies of the Grand Lodge of Louisiana which strictly excluded Black and mixed-race individuals. The Grand Lodge of Louisiana retaliated by breaking relations with the Grand Orient de France in 1869 followed by many other American Grand Lodges. This was a pivotal moment that exemplified the diverging paths of Liberal and Conservative Freemasonry. The Grand Orient stood firmly for racial equality, and the following year it passed a resolution declaring that "neither color, race, nor religion should disqualify a man for initiation."[23] This principle of racial equality would become a defining feature of Liberal Freemasonry, while many Conservative American Grand Lodges maintained racial segregation well into the 20th century.[24][25]

Several American conservative Grand Lodges maintained relations with the GOdF well into the 20th century, including those of California, Washington, and Iowa. The final rupture between American and French Masonry would not occur until after the GOdF's 1877 reforms regarding religious belief.[26]

The 1877 Reform and Freedom of Conscience

[edit]The defining moment for Liberal Freemasonry came during the GOdF's constitutional convention of September 1877. Following extensive debate, and after the key argument of a pastor, the assembly voted to modify Article 1 of the Constitution, which had previously required belief in God and the immortality of the soul.[27]

Protestant pastor Frédéric Desmons, representing the lodge "Le Progrès" of Nîmes, presented the key argument for reform. In his documented speech to the convention, Desmons argued that mandatory religious belief contradicted masonic principles of intellectual liberty and universal brotherhood and that since Freemasonry was not a religion, it should not require a belief in a religious system. The convention adopted his position by a significant majority vote of 135 to 76.[28]

The constitutional changes involved three specific modifications:

- Removal of the requirement to profess belief in deity

- Making the presence of sacred texts optional rather than mandatory

- Replacing references to the "Great Architect of the Universe" with "At the Glory of Humanity"[29]

Global Expansion and Social Progress (1877-1914)

[edit]

Following the 1877 reform, Liberal Freemasonry gained significant importance and expanded rapidly beyond France. The Mexican National Rite, established in 1833,[30] had already embraced similar principles of religious liberty and would formally align with the Liberal tradition.[31]

In France, masonic lodges contributed to, though were not solely responsible for, several major social reforms. Lodge records from this period show consistent advocacy for secular education, separation of church and state, and women's rights. Many prominent politicians of the french Third Republic were freemasons, including Jules Ferry and Léon Gambetta, though their masonic membership was only one aspect of their political identity.[32]

A landmark development was the founding of Le Droit Humain in 1893, which evolved from earlier "adoption lodges" that had admitted women under male supervision. Maria Deraismes became the first woman initiated into a regular French lodge in 1882, leading to the establishment of truly mixed-gender Freemasonry. By 1900, Le Droit Humain had established lodges in France, Belgium, and England.[33]

Persecution and Resistance (1914-1945)

[edit]During both World Wars, Liberal Freemasonry, mainly located in continental Europe, faced severe persecution, particularly under totalitarian regimes. The anti-masonic policies began in Spain under Francisco Franco in 1936 and intensified following the Nazi rise to power. The German Enabling Act of 1933 led to the systematic closure of masonic lodges across Germany.[34]

The Nazi regime targeted Freemasons as part of their broader campaign against what they termed "Judeo-masonic conspiracy." In occupied territories, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) was specifically tasked with confiscating masonic archives and artifacts.[35] In Vichy France, the regime enacted specific anti-masonic legislation with the law of August 13, 1940. The Service des Sociétés Secrètes (SSS)[36] was established to confiscate masonic property and documentation. The SSS occupied the Grand Orient de France headquarters at rue Cadet, converting it into an "Anti-Masonic Exhibition" center.[37]

Perhaps the most remarkable example of masonic resistance was the creation of the Liberté chérie Lodge within Esterwegen concentration camp in 1943. Founded by seven Belgian Freemasons on November 15, 1943, this lodge managed to hold ten meetings between its founding and 1944.[38] The lodge conducted full masonic ceremonies, including an initiation, within the confines of the camp. Only two members of Liberté chérie survived the war.[39]

Official records indicate that during this period:

- Over 989 French Freemasons died in concentration camps

- 20,000 were systematically investigated and persecuted

- The entire masonic library and archives of the Grand Orient were seized and transported to Germany

- 80% of identified masonic property was confiscated

- 60% of French masonic temples were destroyed or severely damaged[40]

Many Liberal Freemasons joined resistance movements across Europe. In France, the masonic network "Patriam Recuperare" worked closely with the French Resistance, establishing communication networks and escape routes. Notable resistance figures included Pierre Brossoletteand Paul Chevallier, both prominent members of the Grand Orient.[41] Similar resistance networks operated in Belgium and the Netherlands, often working in coordination with British intelligence services. The Dutch Grand Orient maintained underground operations throughout the occupation, helping to protect Jewish citizens and downed Allied airmen.[42]

The Rise of International Liberal Masonic Organizations (1961-1989)

[edit]The 1960s marked a period of significant transformation for Liberal Freemasonry. The creation of CLIPSAS in 1961 provided the first formal international structure for Liberal masonic cooperation. Eleven sovereign masonic bodies signed the Strasbourg Appeal, establishing principles for international Liberal masonic relations that remain influential today.[43]

During the May 1968 events in France, Liberal Freemasonry played a significant role in social dialogue. The Grand Orient de France officially supported student and worker rights, while maintaining its traditional role as a space for reasoned debate. This period saw increased engagement with contemporary social issues, including environmentalism and feminism.[44]

The 1970s and 1980s saw increased discussion about gender integration within traditionally male Liberal obediences. While Le Droit Humain had practiced mixed-gender Freemasonry since 1893, other Liberal masonic bodies maintained gender separation well into the late 20th century. The Grande Loge Féminine de France (GLFF), founded in 1945, emerged as a major women-only obedience, demonstrating the continuing importance of separate gender spaces in Liberal Freemasonry.[45]

Significant changes regarding gender policies wouldn't begin until the early 21st century. In 2010, the Grand Orient de France voted to allow individual lodges to decide whether to initiate women, though implementation has varied among lodges.[46][47][48]

The creation of CLIPSAS (Centre de Liaison et d'Information des Puissances maçonniques Signataires de l'Appel de Strasbourg) in 1961 marked a watershed moment for Liberal Freemasonry. Eleven sovereign masonic bodies, including the Grand Orient de France, Grand Orient of Belgium, and Swiss Alpine Grand Lodge, signed the Strasbourg Appeal establishing the first formal international structure for Liberal masonic cooperation[49] The organization aimed to:

- Promote cooperation between Liberal masonic bodies

- Defend freedom of conscience in Freemasonry

- Support the development of Liberal Freemasonry worldwide

- Facilitate exchange between different masonic traditions[50]

End of the Cold War and Eastern European Revival (1989-2000)

[edit]The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and subsequent collapse of communist regimes led to a significant revival of Liberal Freemasonry in Eastern Europe. Many lodges that had been forced underground or into exile were able to resume open operations, which led to a growth of Liberal Freemasonry with, amongst others, the Grand Orient de Roumanie[51] or the Grand Orient of Poland[52] resuming their work.

Global Evolution and Growth (2000-2024)

[edit]The early 21st century marked a period of significant growth for Liberal Freemasonry worldwide, contrasting with declining membership in Conservative Freemasonry. As of 2024, Liberal Freemasonry has established a strong presence across multiple continents, with notable growth in Latin America, Africa, and parts of Asia.[53][54]

Gender Integration

[edit]A defining trend of this period has been the movement toward gender integration. In 2010, the Grand Orient de France voted to allow individual lodges to decide whether to initiate women. Several other traditionally male Liberal obediences have followed similar paths, though implementation varies by region and lodge.[55]

International Cooperation

[edit]Liberal Freemasonry has strengthened its international networks through several organizations:

- CLIPSAS: Over 100 member obediences worldwide[56]

- TRACIA: Coordinating Liberal bodies across Europe and Latin America[57]

- UMM: Uniting Mediterranean masonic bodies[58]

Liberal Masonic Landmarks

[edit]The Liberal Masonic core principals,[59] sometimes called Landmarks or Charter of Values,[60] are not as 'set in stone' as Conservative Masonry, the most common Fundamental Principles are;

Freedom of Conscience

[edit]The most defining characteristic of Liberal Freemasonry is absolute freedom of conscience, formally adopted by the Grand Orient de France in 1877 but practiced earlier by some bodies like the Mexican National Rite.[29] This principle:

- Affirms that philosophical and religious beliefs are matters of personal choice

- Rejects any requirement for belief in a supreme being or religious doctrine

- Allows equal participation by theists, agnostics, and atheists

- Views Freemasonry as a philosophical and initiatic tradition rather than a religious or spiritual system

Universal Brotherhood

[edit]Liberal Freemasonry emphasizes universal brotherhood without distinction of:

- Race or ethnicity

- Religious belief or non-belief

- Gender (in many modern Liberal obediences)

- Social class or economic status

- National origin or cultural background

This principle was demonstrated historically through the Grand Orient de France's recognition of racially integrated lodges in Louisiana in 1868, significantly predating racial integration in Conservative American Freemasonry.[61]

Democratic Governance

[edit]Liberal masonic bodies are characterized by democratic organizational structures that include:

- Election of all officers at lodge and grand lodge levels

- Equal voting rights for all member lodges

- Regular assemblies (convents) where policy is determined by democratic vote

Term limits for leadership positions

- Transparency in governance and decision-making

Progressive Social Engagement

[edit]Unlike Conservative Freemasonry's prohibition on political discussion, Liberal Freemasonry encourages:

- Open discussion of social and political issues in lodges

- Engagement with contemporary societal challenges

- Support for progressive social reforms

- Defense of secular education and scientific inquiry

- Advocacy for human rights and social justice

Initiatic Tradition

[edit]While maintaining freedom of conscience, Liberal Freemasonry strongly preserves traditional masonic elements including:

- Ritual initiation ceremonies

- Use of symbolism derived from operative masonry

- Progressive system of degrees

- Emphasis on self-improvement and ethical development

- Study of philosophy and symbolism

- Longer journey and depth of learning

Implementation

[edit]These principles are implemented differently among Liberal masonic bodies. Some organizations, like Le Droit Humain, practice complete gender integration, while others maintain separate men's, women's, or mixed lodges. Similarly, some bodies focus more intensely on social activism while others emphasize philosophical study.[62] These landmarks distinguish Liberal Freemasonry from Conservative Freemasonry, which generally maintains requirements for belief in a supreme being, restricts membership to men, and prohibits discussion of political or religious topics in lodges.[63]

Relationship with the Catholic Church

[edit]Liberal Freemasonry has been concentrated in traditionally Catholic countries and has been seen by Catholic critics as an outlet for anti-Catholic disaffection.[64] Many particularly anti-clerical regimes in traditionally Catholic countries were perceived as having strong Masonic connections.[65]

The 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia credited Freemasonry for the French Revolution and its persecution of the Church, citing a claim made in a document from the Grand Orient de France.[66] The Encyclopedia saw Freemasonry as the primary force of French anti-clericalism from 1877 onwards, again citing official documents of French Masonry to support its claim.[67] According to one historian, Masonic hostility continued into the early twentieth century with the Affaire Des Fiches[68][69][70] and, according to the old Catholic Encyclopedia, the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State[71][72] can be credited to the Grand Orient de France, based on Masonic documents.

In Italy, the Church linked the anticlerical and nationalist secret society, the Carbonari, to Freemasonry[73] and blamed the anticlerical direction of Italian Unification, or Risorgimento, on Freemasonry. Into the 1890s the Church would justify its calls for Catholics to avoid dealings with the Italian state with a reference to the state's supposed "Masonic" nature.[74]

Mexican Freemasonry was also seen as following the pattern of Liberal Freemasonry in other Latin-speaking countries, viewed as becoming more anti-clerical during the nineteenth century, particularly because they adopted the Scottish Rite degree system created by Albert Pike, which the Catholic Church saw as anti-clerical.[75]

Liberal Freemasonry across the world

[edit]Continental style Lodges exist in most regions of the world. Throughout Continental Europe, Latin America, most of the Caribbean and most of Africa, they are the predominant tradition of Freemasonry, while in the United States of America, the British Commonwealth, and those nations colonized by these powers they are virtually non-existent.

Latin America and the Caribbean

[edit]Throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, both Continental and Anglo-American, conservative jurisdictions exist but Continental style Masonic Bodies predominate. In Brazil, for example, the largest and oldest Masonic body, the Grande Oriente do Brasil is recognised by Anglo-American jurisdictions. Nevertheless, when its membership numbers are compared to the members of all of the Continental style Masonic Bodies, it remains a minority.[76]

In many Latin American countries, the Masonic split has mirrored political divisions. Rivalry between two factions in Mexican Freemasonry is said to have contributed to the Mexican civil war.[77]

Continental Europe

[edit]

France

[edit]Continental style Freemasonry originated in France and its members make up the overwhelming majority of Freemasons in the nation. The Grand Orient de France is the largest Masonic jurisdiction, with the Grande Loge de France (also within the Continental tradition) second in membership. The third largest Masonic body is the Anglo-American style Grande Loge Nationale Française. The International Order of Freemasonry for Men and Women Le Droit Humain founded in 1893 has 32,000 members in more than 60 countries.[78]

Other European countries

[edit]Continental style Freemasonry is prevalent in most of the continent (as its name suggests), although there are smaller numbers of members following the Anglo-American tradition in those nations also. Liberal Freemasonry is present in the majority in most European countries. However, in Germanic states, Anglo-American and Swedish Rite traditions predominate.

North America

[edit]Although some Continental style organizations exist in the United States of America, they are a tiny minority there and have substantially larger (but still minor) numbers in Canada. In Mexico, however, Liberal Freemasonry dominates. These Grand Lodges, Grand Orients and Masonic Orders usually belong to international organizations such as CLIPSAS, SIMPA, CIMAS, COMAM, GLUA and others.

Within the United States of America there are scattered Masonic Orders and Grand Lodges, such as the George Washington Union (GWU),[79] and Le Droit Humain,[80] that belong to the Continental or Progressive Universal Tradition. The Women's Grand Lodge Of Belgium (GLFB or WGLB),[81] and the Feminine Grand Lodge of France[82] also have liberal lodges in North America.

Africa

[edit]Liberal Freemasonry holds the majority in some nations, especially in French and Portuguese speaking areas (but is minority in English speaking areas). It tends to originate from former colonies of France, Portugal and Belgium and Belgian. African leaders such as Pascal Lissouba of the Republic of the Congo belong to Masonic lodges allied with Liberal Freemasonry.[83]

References

[edit]- ^ "Liberal Freemasons - Continental (Progressive) Freemasonry". FREEMASONRY.network. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "R∴ Humanist Lodge - Liberal Freemasonry". www.humanistlodge.org. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Masonica | CONTINENTAL LODGES". Universal Co-Masonry. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "TWO CONCEPTS OF FREEMASONRY". Liberal Grand Lodge of Serbia. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Non-theistic Freemasonry, by Roy Vrizent". Naturalistic Paganism. 11 June 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Rites, Lodges and Obediences - ORDRE MAÇONNIQUE MIXTE INTERNATIONAL LE DROIT HUMAIN". ORDRE MAÇONNIQUE MIXTE INTERNATIONAL LE DROIT HUMAIN. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ https://lodgefoc.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/66d962_cd9b9f8cee7b472f85493ad469dfcb61-1.pdf

- ^ Ligou, Daniel (2000). Histoire des Francs-Maçons en France (in French). Privat. ISBN 2708968386.

- ^ "Masonic Encyclopedia Entry On Montesquieu, a Mason". masonicshop.com. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ Brengues, Jacques (1979). "Franc-maçonnerie et Lumières en 1778: le cas Voltaire". Revue d'Histoire littéraire de la France. 79 (2/3): 244–250. ISSN 0035-2411.

- ^ "Le marquis de La Fayette, major général des armées des États-Unis d'Amérique, en pied". BnF Essentiels (in French). Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Benjamin Franklin et la loge des Neuf Sœurs". BnF Essentiels (in French). Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ Jacob, Margaret C. (1991). Living the Enlightenment: Freemasonry and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195070507.

- ^ Combes, André (1998). Histoire de la Franc-Maçonnerie au XIXe siècle (in French). Éditions du Rocher. ISBN 9782268031637.

- ^ Sudarskis, Solange (14 July 2023). "Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité : de l'idéal au réel en Franc-maçonnerie ?". 450.fm - Journal de la Franc-maçonnerie (in French). Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ Porset, Charles (2013). Les Francs-maçons et la Révolution (in French). Tallandier. pp. 156–178. ISBN 979-1021002418.

- ^ "7055-5 : Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité". www.ledifice.net. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Mirabeau Franc-maçon by Honoré-Gabriel de Riquetti comte de Mirabeau | Open Library". Open Library. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Napoleon, the Masonic Emperor". Vrijmetselaarswinkel. 8 May 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Napoleon the Freemason Emperor | The M.K. Oginski Masonic Lodge in Minsk, Belarus". Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ Révauger, Cécile (2008). The Abolition of Slavery: The British and French Experience. Louisiana State University Press. pp. 89–112. ISBN 978-0807133750.

- ^ Mollier, Pierre (2005). La Franc-maçonnerie sous l'Empire (in French). Éditions Maçonniques de France. ISBN 978-2903846831.

- ^ "godf-ameriqueLa FM en Amerique du Nord". godf-amerique (in French). Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ Combes, André (2009). "Paix, reconstruction et fraternité : la franc-maçonnerie au sortir de la 1ère Guerre mondiale". La Chaîne d'Union (in French). 49 (3): 26–37. doi:10.3917/cdu.049.0026. ISSN 0292-8000.

- ^ "Prince Hall Masons". www.searchablemuseum.com. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of Iowa". Grand Lodge of Iowa Bulletin. 1918.

- ^ Ligou, Daniel (1982). Frédéric Desmons et la Franc-Maçonnerie sous la IIIe République (in French). Gedalge.

- ^ Desmons, Frédéric (1877). Discours au Convent du Grand Orient de France (in French). Bulletin du Grand Orient de France.

- ^ a b Combes, André (1999). La Franc-Maçonnerie Française au XIXe siècle (1814-1914) (in French). Éditions du Rocher. ISBN 9782268032159.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Gould, Robert Freke (1906). A Library of Freemasonry : comprising its history, antiquities, symbols, constitutions, customs, etc., and concordant orders of Royal Arch, Knights Templar, A. A. S. Rite, Mystic Shrine, with other important Masonic information of value to the fraternity derived from official and standard sources throughout the world from the earliest period to the present time. University of California Libraries. London ; Philadelphia : John C. Yorston.

- ^ York, Antonio (2012). Historia de la Masonería en México (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- ^ Nord, Philip (1995). The Republican Moment: Struggles for Democracy in Nineteenth-Century France. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674762701.

- ^ Martin, Georges (1900). Archives de l'Ordre Maçonnique Le Droit Humain (in French). DH Archives.

- ^ Bernheim, Alain (2022). Les Francs-Maçons face à Hitler (in French). Dervy. ISBN 978-2844549785.

- ^ Krüger, Wolfgang (1982). Wir waren Feinde der Nation (in German). Wien. pp. 156–189.

- ^ "Le procès des dirigeants du service des sociétés secrètes" (in French). 25 November 1946. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ Rossignol, Dominique (1981). Vichy et les Francs-maçons (in French). J.C. Lattès. ISBN 978-2709602280.

- ^ Van Der Linden, Luc (2012). Liberté chérie: Une loge maçonnique dans un camp de concentration (in French). Editions Labor. pp. 45–67. ISBN 978-2874158384.

- ^ Perl, William (1989). The Holocaust Conspiracy. Shapolsky Publishers. ISBN 9780944007242.

- ^ Marcos, Jacques (2017). Les Francs-maçons sous l'Occupation (in French). Éditions du Rocher. ISBN 978-2268095561.

- ^ Naudon, Paul (1975). La Résistance maçonnique (in French). Gedalge.

- ^ van Loo, Petra (2007). Vrijmetselarij in Nederland (in Dutch). Boom. ISBN 978-9085064541.

- ^ Billaud, Patrice (2011). "Le CLIPSAS, 50 ans après". Humanisme (in French). 294 (4): 89–91. doi:10.3917/huma.294.0089. ISSN 0018-7364.

- ^ Reed, Ernest. "May 1968: Workers and students together | International Socialist Review". isreview.org. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ Hivert-Messeca, Gisèle (2015). Femmes et Franc-maçonnerie (in French). Dervy. ISBN 978-2844549754.

- ^ Mollier, Pierre (2011). "La mixité dans la franc-maçonnerie libérale". Renaissance Traditionnelle (in French).

- ^ Guide, Le (6 February 2024). "La mixité en franc-maçonnerie". Le Guide suprême de la Franc-Maçonnerie (in French). Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Rites, Lodges and Obediences - ORDRE MAÇONNIQUE MIXTE INTERNATIONAL LE DROIT HUMAIN". ORDRE MAÇONNIQUE MIXTE INTERNATIONAL LE DROIT HUMAIN. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Appel de Strasbourg – CLIPSAS". clipsas.org (in French). Archived from the original on 25 January 2025. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ https://clipsas.org/en/appel-de-strasbourg/

- ^ "La Franc-Maçonnerie en Roumanie". GOB (in French). Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ https://wielkiwschod.pl/en/

- ^ Naudon, Paul (2009). "La franc-maçonnerie dans le monde". Que sais-je ? (in French). 18: 62–70. ISSN 0768-0066.

- ^ Hivert-Messeca, Yves (2017). "Trois cents ans de franc-maçonnerie dans le monde". La Chaîne d'Union (in French). 81 (3): 20–29. doi:10.3917/cdu.081.0020. ISSN 0292-8000.

- ^ Bu, Peter (2011). "De l'initiation des femmes et de la mixité". La Chaîne d'Union (in French). 57 (3): 57–65. doi:10.3917/cdu.057.0057. ISSN 0292-8000.

- ^ "CLIPSAS members". FREEMASONRY.network. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "Grand Masonic Alliance TRACIA – The Square Magazine". Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ "M.M.U. (Masonic Mediterranean Union)". FREEMASONRY.network. Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ The World List of Liberal-Continental Masonic Grand Orients and Grand Lodges. 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Charte des valeurs du Grand Orient de France". Humanisme (in French). 293 (3): 12–14. 2011. doi:10.3917/huma.293.0012. ISSN 0018-7364.

- ^ Révauger, Cécile (2016). Black Freemasonry: From Prince Hall to the Giants of Jazz. Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-1620554876.

- ^ "Devenir Franc-Maçon - ORDRE MAÇONNIQUE MIXTE INTERNATIONAL LE DROIT HUMAIN". ORDRE MAÇONNIQUE MIXTE INTERNATIONAL LE DROIT HUMAIN (in French). Retrieved 29 January 2025.

- ^ Librairie, La Petite. Les francs-maçons, architectes de l'avenir, sur la voie du XXIe siècle - Alain Pozarnik - Dervy (in French).

- ^ Whalen, William A. (27 June 1985). "The Pastoral Problem of Masonic Membership". Catholic Culture. Catholic News Service/U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

Everyone knows that the Grand Orient Lodges of Europe and Latin America have been anti-clerical from the start. For the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to advise Catholics against joining these Grand Orient Lodges would be like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People advising blacks against applying for membership in the Ku Klux Klan

- ^ Johnston, Charles (24 February 1918). "Caillaux's Secret Power Through French Masonry" (PDF). The New York Times Magazine. p. 71. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

So far does this militant atheism of 'Latin Freemasonry' in France go,…

- ^ Gruber, Hermann (1910). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9.

(Footnote 163 cites the Circular of the Grand Orient of France thus: Masonry, which prepared the Revolution of 1789, has the duty to continue its work

- ^ Gruber, Hermann (1910). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9.

VII. Outer work, thus: French Masonry and above all the Grand Orient of France has displayed the most systematic activity as the dominating political element in the French "Kulturkampf" since 1877

- ^ Franklin, James (2006). "Freemasonry in Europe". Catholic Values and Australian Realities. Connor Court Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 9780975801543. OCLC 1155224329.

- ^ Larkin, Maurice (1974). Church and State after the Dreyfus Affair: The Separation Issue in France. pp. 138–141. ISBN 9780333147030. OCLC 1047673785.

- ^ "Freemasonry in France". Austral Light. 6: 164–172, 241–250. 1905.

- ^ Gruber, Hermann (1910). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9.

VII. Outer Work. In truth all the 'anti-clerical' Masonic reforms carried out in France since 1877, such as the secularization of education, measures against private Christian schools and charitable establishments, the suppression of the religious orders and the spoliation of the Church, professedly culminate in an anti-Christian and irreligious reorganization of human society, not only in France but throughout the world....

- ^ Goyau, Georges (1967). "France". New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 135. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

From the fall of the MacMahon government in 1877 to the start of World War II, Masonic politicians controlled the French government. They passed anticlerical laws designed to restrict the Church's influence, especially in education.

- ^ "It also links Freemasonry with the Society of the Carbonari, known as the "Charcoal Burners", who at that time were active in Italy and were believed to be a revolutionary group" (McInvale, Reid (18 June 2013), Roman Catholic Church Law Regarding Freemasonry, Texas Lodge of Research, retrieved 1 August 2013

- ^ "Masonry has confiscated the inheritance of public charity; fill the void, then, with the treasure of private relief" (Pope Leo XIII (1999), Custodi di Quella Fede (Encyclical of Pope Leo XIII promulgated on 8 December 1892), Eternal Word Television Network, p. Para 18).

- ^ "As the 19th Century went on, Mexican Masonry embraced the degree system authored by Albert Pike and grew ever more anticlerical, regardless of Rite" (Salinas E., Oscar J. (Senior Grand Warden-York/Mexico) (10 September 1999), Mexican Masonry – Politics & Religion, archived from the original on 15 June 2011)

- ^ "MIT Freemasonry webpage". Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ Whalen, William J., "Freemasonry", hosted at trosch.org. from New Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 6, pp.132–139. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Organization - Ordre Maçonnique Mixte International Le Droit Humain". Ordre Maçonnique Mixte International le Droit Humain. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ "George Washington Union". George Washington Union. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ The International Order of Freemasonry for Men and Women Le Droit Humain

- ^ Grande Loge Féminine de Belgique and Montréal in Québec Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Feminine Grand Lodge of France Archived 28 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wauthier, Claude. Africa's Freemasons – A strange inheritance, Le Monde diplomatique, September 1997. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch