Libertarian socialism

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarian socialism |

|---|

|

Libertarian socialism is an anti-authoritarian and anti-capitalist political current that emphasises self-governance and workers' self-management. It is contrasted from other forms of socialism by its rejection of state ownership and from other forms of libertarianism by its rejection of private property. Broadly defined, it includes schools of both anarchism and Marxism, as well as other tendencies that oppose the state and capitalism.

With its roots in the Age of Enlightenment, libertarian socialism was first constituted as a tendency by the anti-authoritarian faction of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA), during their conflict with the Marxist faction. Libertarian socialism quickly spread throughout Europe and the American continent, reaching its height during the early stages of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and particularly during the Spanish Revolution of 1936. Its defeat during these revolutions led to its brief decline, before its principles were resurrected by the New Left and new social movements of the late 20th century.

While its key principles of decentralisation, workers' control, and mutual aid are generally shared across the many schools of libertarian socialism, differences have emerged over the questions of revolutionary spontaneity, reformism, and whether to prioritise the abolition of the state or of capitalism.

Political principles

[edit]Libertarian socialism strives for a free and equal society,[1] aiming to transform work and everyday life.[2] Broadly defined, libertarian socialism encapsulates any political ideology that favours workers' control of the means of production and the replacement of capitalism with a system of cooperative economics,[3][4] or common ownership.[5] Libertarian socialists tend to see the working class as agents of social revolution, reject representative democracy and electoralism, and advocate for self-organisation and direct action as means to engage in class conflict.[6]

Anti-authoritarianism

[edit]Libertarian socialism has a grassroots and direct democratic[7] approach to socialism, rejecting parliamentarism and bureaucracy.[8] Libertarian socialists advocate the empowerment of individuals to control their own lives and encourage them to voluntarily cooperate with each other, rather than allow themselves to be controlled by a state. Libertarian socialists therefore uphold civil liberties such as freedom of choice, freedom of expression and freedom of thought.[9]

In contrast to authoritarian forms of socialism, libertarian socialism rejects state ownership and centralisation. Instead it upholds a decentralised model of self-governance, envisioning free association based on co-operative or participatory economics. Some libertarian socialists see such systems as complementary to statism, while others hold them to be an alternative to the state.[9]

Libertarian socialists tend to reject the view that political institutions such as the state represent an inherently good, or even neutral, power.[10] Some libertarian socialists, such as Peter Kropotkin, consider the state to be an inherent instrument of landlordism and capitalism, therefore opposing the state with equal intensity as they oppose capitalism.[11]

Anti-capitalism

[edit]Libertarian socialism views corporate power as an institutional problem, rather than as a result of the influence of certain immoral individuals.[12] It thus opposes capitalism, which it sees as an economic system that upholds greed, the exploitation of labour and coercion, and calls for its overthrow in a social revolution.[13]

Libertarian socialists reject private property, as they consider capitalist property relations to be incompatible with freedom.[9] Instead, libertarian socialism upholds individual self-ownership, as well as the collective ownership of the means of production.[14] In the place of capitalism, libertarian socialists favour an economic system based on workers' control of production, advocating for a system of cooperative economics,[3][4] or common ownership.[5] They also advocate for workers' self-management, as they consider workers able to cooperate productively without supervisors, whether appointed by employers or by the state.[13]

They also tend to see free trade as inevitably resulting in the redistribution of income and wealth from workers to their corporate employers.[15] They advocate for the elimination of social and economic inequality through the coercive expropriation of property from the wealthy.[16]

History

[edit]The roots of libertarian socialism extend back to the classical radicalism of the early modern period,[17] claiming the English Levellers and the French Encyclopédistes as their intellectual forerunners, and admiring figures of the Age of Enlightenment such as Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine.[18] According to Mikhail Bakunin and Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis, while authoritarian socialism had its origins in Germany, libertarian socialism was born in France.[19] The modern foundations of libertarian socialism lay in the utopian socialism expounded by Charles Fourier, Robert Owen and Henri de Saint-Simon, who envisioned a democratic socialism guided by communitarianism, moralism and feminism.[20]

Emergence

[edit]

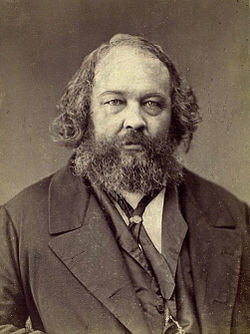

Libertarian socialism first emerged from the anti-authoritarian faction of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA), after it was expelled from the organisation by the Marxist faction at the Hague Congress of 1872.[21] The libertarian socialist Mikhail Bakunin had rejected Karl Marx's calls for a "dictatorship of the proletariat", as he predicted it would only create a new ruling class, composed of a privileged minority, which would use the state to oppress the working classes. He concluded that: "no dictatorship can have any other aim than to perpetuate itself, and it can only give rise to and instill slavery in the people that tolerates it."[22] Marxists responded to this by insisting on the eventual "withering away of the state", in which society would transition from dictatorship to anarchy, in an apparent attempt to synthesise authoritarian and libertarian forms of socialism.[23]

This put libertarian socialists into direct competition with social democrats and communists for influence over left-wing politics, in a contest which lasted for over fifty years.[21] Libertarian socialism proved attractive to British writers such as Edward Carpenter,[24][25][26] Oscar Wilde,[27] and William Morris, the latter of whom developed a kind of libertarian socialism based in a strong critique of civilisation, which he aimed to overthrow and replace with what he called a "beautiful society".[28] Morris drove the development of impossibilism, which became increasingly concerned with the bureaucratisation and moderation of the socialist movement, leading to the establishment of the Socialist Party of Great Britain.[29]

By the early 20th century, libertarian socialists had gained a leading influence over the left-wing in the Netherlands, France and Italy and went on to play major roles in the Mexican and Russian Revolutions.[21] In India, the libertarian socialist tradition was represented in the early twentieth century anti-colonial movement by Bhagat Singh.[30]

Russian Revolution

[edit]

Russian libertarian socialists, including anarchists, populists and left socialist-revolutionaries, led the opposition to the Tsarist autocracy throughout the late-19th century.[31] They created a network of both clandestine and legal organisations throughout Russia, with the aim of overthrowing the Russian nobility and bringing land under the common ownership of the mir. Their agitation for land reform in the Russian countryside culminated with the establishment of rural soviets during the 1905 Revolution.[32]

Anarchists also organised among the urban proletariat, forming clandestine factory committees that proved more attractive to revolution-minded workers than the more reformist trade unions favoured by the Bolsheviks. During the 1917 Revolution, in which libertarian socialists played a leading role, the Bolsheviks changed tack and adopted elements of the libertarian socialist programme in their appeals to the workers. But by 1919, the new Bolshevik government had come to view the libertarian socialists as a threat to their power and moved to eliminate their influence. Libertarian socialist organisations were banned and many of their members were arrested, deported to Siberia or executed by the Cheka.[33]

The Revolutions of 1917–1923 ended in defeat for the libertarian socialists, with either the social democrats, the Bolsheviks or nationalists rising to power. Libertarian socialists responded by reevaluating their positions, emphasising mass organisation over intellectual vanguardism and revolutionary spontaneity over substitutionism.[34] They also came to conceive the "dictatorship of the proletariat" as a form of class power, rather than as the dictatorship of a political party. Many Marxists of the period were attracted to this position, including Rosa Luxemburg in Germany, Antonie Pannekoek in the Netherlands, Sylvia Pankhurst in Britain, György Lukács in Hungary and Antonio Gramsci in Italy.[35]

Spanish Revolution

[edit]

Libertarian socialism reached its apex of popularity with the Spanish Revolution of 1936, during which libertarian socialists led "the largest and most successful revolution against capitalism to ever take place in any industrial economy".[21]

In Spain, traditional forms of self-management and common ownership dated back to the 15th century. The Levante, where collective self-management of irrigation was commonplace, became the hotbed of anarchist collectivisation.[36] Building on this traditional collectivism, from 1876, the Spanish libertarian socialist movement grew through sustained agitation and the establishment of alternative institutions that culminated in the Spanish Revolution.[37] During this period, a series of workers' congresses, first convoked by the Spanish Regional Federation of the IWA, debated and refined proposals for the construction of a libertarian socialist society. Over several decades, resolutions from these congresses formed the basis of a specific program on a range of issues, from the structure of communes and the post-revolutionary economy to libertarian cultural and artistic initiatives.[38] These proposals were published in the pages of widely distributed libertarian socialist periodicals, such as Solidaridad Obrera and Tierra y Libertad, which each circulated tens of thousands of copies. By the outbreak of the revolution, the anarcho-syndicalist Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) enjoyed widespread popularity, counting 1.5 million members within its ranks.[39]

During the revolution, the means of production were brought under workers' control and worker cooperatives formed the basis for the new economy.[40] According to Gaston Leval, the CNT established an agrarian federation in the Levante that encompassed 78% of Spain's most arable land. The regional federation was populated by 1,650,000 people, 40% of whom lived on the region's 900 agrarian collectives, which were self-organised by peasant unions.[41]

Although industrial and agricultural production was at its highest in the anarchist-controlled areas of the Spanish Republic, and the anarchist militias displayed the strongest military discipline, liberals and Communists alike blamed the "sectarian" libertarian socialists for the defeat of the Republic in the Spanish Civil War. These charges have been disputed by contemporary libertarian socialists, such as Robin Hahnel and Noam Chomsky, who have accused such claims of lacking substantial evidence.[42]

Decline

[edit]Following the defeat of the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, libertarian socialism fell into decline.[43] Left-wing politics throughout the world came to be dominated either by social democracy or Marxism-Leninism, which attained power in a number of countries and thus had the means to support their ideological allies. In contrast, Hahnel argues, libertarian socialists were not able to gain influence within the labour movement. At a time when reformist trade unions were consistently winning concessions, the libertarian socialists' anti-reformist message gained little traction. Their platform of workers' self-management also failed to appeal to industrial workers.[44] Until the 1960s, libertarian socialists were limited mostly to making critiques of authoritarian socialism and capitalism, although Hahnel asserts that these arguments were largely overshadowed by those from neoconservatives and Marxists respectively.[45]

New Left

[edit]

Libertarian socialist themes received a revival during the 1960s, when it was reconstituted as part of the nascent New Left.[46] This revival occurred largely unconsciously, as new leftists were often unaware of their libertarian socialist predecessors. The concepts of grassroots democracy, workers' control, solidarity and autonomy were thus reinvented by the new generation.[47] They also picked up the principles of decentralisation, participatory democracy and mutual aid.[48] These libertarian socialist themes drove the growth of the New Left, which by this point was disillusioned by the mainstream social democratic and Marxist-Leninist political groupings, due to the capitalistic tendencies of the former and the rigid authoritarianism of the latter.[46]

Sociologist C. Wright Mills, who displayed strong libertarian socialist tendencies in his appeals to the New Left, reformulated Marxism for the modern age in his work on The Power Elite (1956). Wilhelm Reich's Freudo-Marxist theses on the authoritarian personality were also rediscovered by the New Left, who developed his programme for individual self-governance into a libertarian system of education used by the Summerhill School.[49] Drawing on the Freudo-Marxist conception of civilisation as "organised domination", Herbert Marcuse developed a critique of alienation in modern Western societies, concluding that creativity and political dissent had been undermined by social repression. Meanwhile, Lewis Mumford published denunciations of the military-industrial complex and Paul Goodman advocated for decentralisation.[48] In the process, the new generation of Marxists gravitated towards libertarian tendencies, sometimes closely resembling anarchism. Following on from Marcuse, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, E. P. Thompson, Raymond Williams and Stuart Hall all adopted forms of "libertarian Marxism", opposed to the bureaucracy and parliamentarism of statist tendencies.[50]

A specific and explicit libertarian socialist tendency also began to emerge. While some more libertarian Marxists adopted the term in order to distinguish themselves from authoritarian socialists,[51] anarchists began calling themselves "libertarian socialist" in order to avoid the negative connotations associated with anarchism.[52] The libertarian socialist Daniel Guérin specifically attempted to synthesise anarchism and Marxism into a single tendency, which inspired the growth of the French libertarian communist movement.[53] For a time, even the American anarcho-capitalist theorist Murray Rothbard attempted to make common cause with libertarian socialists, but later shifted away from socialism and towards right-wing populism.[54]

Many libertarian socialists of this period were particularly influenced by the analysis of Cornelius Castoriadis[55][56] and his group Socialisme ou Barbarie.[57] This new generation included the non-vanguardist Marxist organisation Facing Reality,[58] the British libertarian socialist group Solidarity,[59][60] and the Australian councilists of the Self-Management Group.[61] Some of this new generation of libertarian socialists also joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), swelling the old union's numbers, organising agricultural workers and launching a new journal, The Rebel Worker.[58] This libertarian socialist milieu, with their criticisms of democratic centralism and trade unionism, and their advocacy of workers' self-management and council democracy, went on to inspire the French situationists and Italian autonomists.[62]

Of the figures in the New Left, the American linguist Noam Chomsky became the most prominent spokesperson for libertarian socialism.[17] Inspired by the humanism of Bertrand Russell, the individualism of Wilhelm von Humboldt and the syndicalism of Rudolf Rocker, Chomsky championed a libertarian socialism that upheld individual liberty and self-ownership.[63] Chomsky has been outspoken advocate of anti-authoritarianism, opposing limits on individual freedoms by the state.[64] He has also focused much of his libertarian socialist critique on mass media in the United States, due to its role in the military-industrial complex.[65]

While most sections of the New Left expressed a form of libertarian socialism, others were instead being inspired by the Cuban and Chinese Communist Revolutions to embrace forms of authoritarian socialism such as Maoism–Third Worldism.[66] As such, according to Hahnel, the New Left failed to form a coherent ideological program or establish lasting support to carry forward the momentum of the late 1960s, resulting in many dropping out of activism altogether.[67]

New social movements

[edit]A minority from the New Left continued their radical activism within the new social movements of the 1970s and 1980s, becoming involved in second-wave feminism, the gay liberation movement, environmental movement and eventually the anti-globalization movement.[67] In this period, many libertarian socialists, such as Murray Bookchin, Cornelius Castoriadis, André Gorz, Ivan Illich, E.P. Thompson and Raymond Williams, were committed to " in rethinking what socialism might come to mean in an age of ecological limit".[68]

According to Robin Hahnel, new social movements continued the New Left's tendency of failing to develop a "comprehensive libertarian socialist theory and practice". Libertarian socialist activism became focused on achieving practical reforms and theoretical developments centred around common "core values" such as economic democracy, economic justice and sustainable development, without building a coherent critique of capitalism.[69] Activists from the 1970s and 1980s influenced by libertarian socialism did not advance coherent alternatives to markets and central planning, and had no reformist campaign. Eventually, Hahnel argues, they turned to traditional single-issue campaigns and abandoned their "big picture" libertarian socialist approach.[70]

These movements were somewhat successful in achieving their goals: the movements for gay and women's rights changed societal outlook on gender oppression; the anti-racist movement proved it necessary to tackle the social aspects of racialisation; the anti-imperialist movement reconceived of anti-imperialism outside of economic terms; and the environmentalist movement launched a wave of ecological defense and restoration. Together, Hahnel argues, they broke from the class reductionism prevalent in traditional forms of libertarian socialism, proving intersectional oppressions other than class also demanded attention.[71] Through the new social movements, libertarian socialism developed an awareness of different aspects of oppression, beyond class analysis.[72]

Contemporary era

[edit]Libertarian socialism again received a revival of interest in the wake of the fall of communism and concurrent rise of neoliberalism.[43] It proved particularly attractive to people from the former Eastern Bloc, who saw it as an alternative both to western capitalism and Marxism-Leninism.[73] Since the end of the Cold War, there have been two major experiments in libertarian socialism: the Zapatista uprising in Mexico and the Rojava Revolution in Syria.[74]

In reaction against the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the privatisation of indigenous lands by the Mexican state, in 1994, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) rose up against the government,[75] enabling the formation of a self-governing autonomous territory in the Mexican state of Chiapas.[74][75][76] The Zapatistas have roundly rejected political sectarianism and ideological doctrine, including the state socialist model of seizing state power, with spokesman Subcomandante Marcos famously declaring "I shit on all the revolutionary vanguards of this planet."[74] As such, they have commonly been characterised as libertarian socialist,[74][76] or inspired by libertarian socialism.[75][77] They have in turn become a source of inspiration for libertarian socialists, including the autonomist Marxists Harry Cleaver and John Holloway, as well as some anarchists.[74]

In 2012, the Rojava Revolution established the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES; or "Rojava") to put "libertarian socialist ideas ... into practice",[78] and whose cantons present themselves as a "libertarian socialist alternative to the colonially established state boundaries in the Middle East."[74] Various sources have drawn parallels between the Rojava Revolution and the Zapatista uprising of 1994[79] or the Spanish Revolution of 1936,[80] and noted the influence of libertarian socialist Murray Bookchin, specifically his concept of libertarian municipalism, on the revolution.[81][80]

Libertarian socialist ideas have influenced some currents of the anti-austerity and new municipalist movements, such as Ada Colau's Barcelona en Comú party, in which they ally with democratic socialists.[82]

In Chile, there have been several libertarian socialist movements active since the 2010s in groups including Libertarian Left and the Broad Front (FA).[83] Gabriel Boric founded Social Convergence in 2018, bringing together the Autonomist Movement, Libertarian Left and other libertarian socialist groups.[84] Boric, who describes himself as libertarian socialist, was elected president in 2021.[85][86][87]

Notable tendencies

[edit]Libertarian socialism encompasses both the libertarian wing of socialism and the socialist wing of libertarianism,[88] including many different schools of thought under its banner.[89] The most commonly cited tendencies of libertarian socialism are anarchist communism, anarcho-syndicalism, and council communism.[90] Other Marxist strands of libertarian socialism include Western Marxism, Bordigism and impossibilism.[91] Additionally, utopian socialism, guild socialism, socialist feminism and social ecology,[92] as well as various strands of the New Left, new social movements and contemporary anarchism, have been listed among the other wings of libertarian socialism.[3]

Anarchist

[edit]The currents of classical anarchism that developed in the 19th century were committed to autonomy and freedom, decentralization, opposing hierarchy, and opposing the vanguardism of authoritarian socialism.

In the 20th century, social anarchism emerged as a significant current of anarchism and explicitly identified as libertarian socialist. Anarcho-syndicalist Gaston Leval explained: "We therefore foresee a Society in which all activities will be coordinated, a structure that has, at the same time, sufficient flexibility to permit the greatest possible autonomy for social life, or for the life of each enterprise, and enough cohesiveness to prevent all disorder. [...] In a well-organised society, all of these things must be systematically accomplished by means of parallel federations, vertically united at the highest levels, constituting one vast organism in which all economic functions will be performed in solidarity with all others and that will permanently preserve the necessary cohesion".[93]

Significant thinkers in the anarchist tradition who are described as libertarian socialist include Colin Ward and David Graeber.[94][95]

Marxist

[edit]A broad scope of economic and political philosophies that draw on the anti-authoritarian aspects of Marxism have been described as "libertarian Marxism",[96] a tendency which emphasises autonomy, federalism and direct democracy.[96] Wayne Price identified it most closely with the tendency of autonomist Marxism and identified libertarian characteristics within council communism, the Johnson–Forest Tendency, the Socialisme ou Barbarie group and the Situationist International, contrasting them with orthodox Marxism, social democracy, and Marxism–Leninism.[97] Michael Löwy and Olivier Besancenot have identified Rosa Luxemburg, Walter Benjamin, André Breton and Daniel Guérin as prominent figures of libertarian Marxism.[96] Ojeili identifies William Morris, Daniel De Leon, the Socialist Party of Great Britain, Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Korsch Anton Pannekoek, Roland Holst, Hermann Gorter, Sylvia Pankhurst, Antonio Gramsci, György Lukács, Socialisme ou Barbarie, Henri Simon, Échanges et mouvement and Paul Mattick as significant Marxian libertarian socialists.[98]

Democratic socialist

[edit]There was a strong left-libertarian current in the British labour movement[99] and the term "libertarian socialist" has been applied to a number of democratic socialists, including some prominent members of the British Labour Party.[100] The Socialist League was formed in 1885 by William Morris and others critical of the authoritarian socialism of the Social Democratic Federation.[28] It was involved in the new unionism, the rank-and-file union militancy of the 1880s–1890s, which anticipated syndicalism in some key ways (Tom Mann, a New Unionist leader, was one of the first British syndicalists). The Socialist League was dominated by anarchists by the 1890s.[101] The Common Wealth Party was inspired by Christian socialism as well as libertarian socialism.[102][103] Others in the tradition of the ILP and described as libertarian socialists included G. D. H. Cole (the founder of guild socialism and influenced by Morris),[104][99][105][106] George Orwell,[107][108] Michael Foot,[109][110] Raymond Williams,[68] and Tony Benn.[111] Another is former Labour Party minister Peter Hain,[112][113][114] who has written in support of libertarian socialism,[105] identifying an axis involving a "bottom-up vision of socialism, with anarchists at the revolutionary end and democratic socialists [such as himself] at its reformist end" as opposed to the axis of state socialism with Marxist–Leninists at the revolutionary end and social democrats at the reformist end.[115][116] Another recent mainstream Labour politician who has been described as a libertarian socialist is Robin Cook.[117]

Debates

[edit]Reasons for decline

[edit]American economist Robin Hahnel claimed that libertarian socialists "were by far the worst underachievers among 20th century anti-capitalists."[118] He contrasted libertarian socialist failings with those of social democracy, arguing that while the latter had abandoned their principles of economic democracy and justice in favour of reformism, the former had proved incapable of sustaining anti-capitalist uprisings and largely ignored the importance of political and economic reform.[119] Hahnel consequently suggested that, in the 21st century, libertarian socialists should work together with other anti-capitalist social movements, organize for reform without abandoning anti-capitalist principles and strive to build grassroots institutions of self-management, even if those projects are "imperfect".[21]

Priorities

[edit]While most libertarian socialists consider it necessary to combat both economic and political power in tandem, regarding each as fundamental to the survival of the other, some consider it a priority to combat one or the other first.[120] Some, such as Mikhail Bakunin and Alexander Berkman, considered capitalism to rely on the support and protection of the state. They thus concluded that if the state were to be abolished, capitalism would naturally dissolve in its wake.[121] But others, including Noam Chomsky, believe that the state is only inherently oppressive because of its control by a plutocratic class and that "society is governed by those who own it". Chomsky holds that government, while not benign, can at least be held accountable, while corporate power is neither benign nor accountable.[122] Though he holds the abolition of the state to be desirable, Chomsky considers the abolition of capitalism to be of greater urgency.[123]

Theoretical coherence

[edit]Libertarian socialism has faced criticism from some scholars who argue that its core principles contain internal contradictions. Economist Robin Hahnel notes that while libertarian socialists advocate for decentralized, anti-authoritarian models of organization, historical attempts to implement such systems—such as during the Spanish Revolution—often struggled with practical challenges like coordinating defense against external threats or maintaining economic efficiency without centralized structures. Hahnel suggests these difficulties stem from tensions between the ideology’s emphasis on radical autonomy and the pragmatic requirements of sustaining large-scale social movements, calling it a "self-limiting" theory that inadvertently undermines its own goals.[124] Similarly, political theorist Noam Chomsky has acknowledged that libertarian socialist ideals, while morally compelling, face inherent logistical hurdles in balancing collective self-management with functional governance, observing that "the gap between doctrine and reality" often reveals unresolved theoretical gaps.[123]

Critics from Marxist traditions, such as J. Moufawad-Paul, argue that libertarian socialism’s rejection of vanguardism and state power leaves it unable to address the consolidation of counter-revolutionary forces, rendering its projects vulnerable to collapse or co-optation. These critiques posit that the theory’s anti-statist foundations conflict with the material realities of class struggle, creating a paradox where its principles "debunk their own applicability."[a]

See also

[edit]- Freiwirtschaft ("free economy"), idea based on the "natural economic order"

- Sociocracy, decentralized governance system based on consent developed in meeting circles

- Libertarianism, a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core principle

References

[edit]- ^ See Moufawad-Paul, J. (2016). Continuity and Rupture: Philosophy in the Maoist Terrain. Zero Books.

- ^ Cornell 2012, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Kinna & Prichard 2012, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Hahnel 2005, p. 392n1.

- ^ a b Frère, Bruno; Reinecke, Juliane (2011). "A Libertarian Socialist Response to the 'Big Society': The Solidarity Economy". In Hull, Richard; Gibbon, Jane; Branzei, Oana; Haugh, Helen (eds.). The Third Sector. UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. pp. 125–126. doi:10.1108/S2046-6072(2011)0000001015. hdl:2268/172850. ISBN 978-1-78052-280-7. ISSN 2046-6072.

The libertarian socialist cooperative movement was one of the two forms of socialist responses to the rise of capitalism and the concentration of private ownership in the middle of the 19th century." "Proudhon's left libertarian socialism promotes the decentralisation of power and public sovereignty ... through the formation of locally managed mutual and cooperative organisations ....

- ^ a b Intropi, Pietro (2022-06-01). "Reciprocal libertarianism". European Journal of Political Theory. 23 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1177/14748851221099659. hdl:2262/98664. ISSN 1474-8851.

I show that reciprocal libertarianism can be realised in a framework of individual ownership of external resources or in a socialist scheme of common ownership (libertarian socialism).

- ^ Pinta & Berry 2012, p. 298.

- ^ Asimakopoulos, John (April–June 2016). "A radical proposal for direct democracy in large societies". Brazilian Journal of Political Economy. 36 (2): 430–447. doi:10.1590/0101-31572016v36n02a10. ISSN 0101-3157.

Direct democracy is what today is referred to as libertarian socialism including anarchism. The very idea upon which libertarian socialism is founded is that every person in the community represents themselves and votes directly with the community on matters related to its governance.

- ^ Kinna & Prichard 2012, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Long 1998, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Long 1998, p. 318.

- ^ Long 1998, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Long 1998, pp. 331–332.

- ^ a b Hahnel 2005, p. 140.

- ^ Vrousalis 2011, p. 211.

- ^ Long 1998, p. 332.

- ^ Long 1998, p. 340.

- ^ a b Long 1998, p. 305.

- ^ Long 1998, p. 310.

- ^ Marshall 2008, p. 484.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, pp. 139–140.

- ^ a b c d e Hahnel 2005, p. 138.

- ^ Long 1998, p. 320.

- ^ Long 1998, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Marshall 2008, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Salveson, Paul (1 October 1996). "Loving Comrades: Lancashire's Links to Walt Whitman". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 14 (2–3): 57–84. doi:10.13008/2153-3695.1500. ISSN 0737-0679.

- ^ Sally Goldsmith (23 March 1929). "Edward Carpenter". Totley History Group. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ Marshall 2008, p. 180.

- ^ a b Marshall 2008, p. 171.

- ^ Ojeili 2001, p. 403.

- ^ Drèze, Jean (3 October 2015). "Anarchism in India". RAIOT. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, p. 141.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, p. 142.

- ^ Ojeili 2001, p. 400.

- ^ Ojeili 2001, pp. 403–404.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, p. 143.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, p. 146.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, p. 145.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, pp. 146–147.

- ^ a b Hahnel 2005, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, p. 147.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, pp. 147–148.

- ^ a b Hahnel 2005, p. 148; Marshall 2008, p. 540.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, p. 148.

- ^ a b Marshall 2008, p. 541.

- ^ Marshall 2008, pp. 540–541.

- ^ Marshall 2008, pp. 541–542.

- ^ Marshall 2008, p. 641.

- ^ Boraman 2012, p. 257; Marshall 2008, p. 641.

- ^ Berry 2012, p. 199.

- ^ Long 1998, p. 310n17.

- ^ Claude Lefort, Writing: The Political Test, Duke University Press, 2000, Translator's Foreword by David Ames Curtis, p. xxiv, "Castoriadis, the historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet, now Lefort ... are themselves quite articulate in their own right and historically associated with a libertarian socialist outlook..."

- ^ Ojeili, Chamsy (2001b). "Post-Marxism with Substance: Castoriadis and the Autonomy Project". New Political Science. 23 (2): 225–239. doi:10.1080/07393140120054047. ISSN 0739-3148.

Receiving his political inheritance from the broad libertarian socialist tradition, Castoriadis continues to challenge the domination of state and capital and to insist on the liberatory possibilities of direct democracy.

- ^ Boraman 2012, p. 252; Cornell 2012, p. 177.

- ^ a b Cornell 2012, p. 177.

- ^ Boraman 2012, pp. 252, 257; Cornell 2012, p. 177; Marshall 2008, p. 495.

- ^ "What is libertarian socialism? An interview with Ken Weller". libcom.org. 26 October 2015. Archived from the original on 24 March 2024. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ Boraman 2012, pp. 251–271.

- ^ Cornell 2012, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Marshall 2008, p. 578.

- ^ Marshall 2008, pp. 578–579.

- ^ Marshall 2008, p. 579.

- ^ Marshall 2008, pp. 542.

- ^ a b Hahnel 2005, pp. 148–149.

- ^ a b Stevenson, Nick (12 July 2018). "Raymond Williams and the possibilities of 'committed' late Marxism". Key Words: A Journal of Cultural Materialism. 16. The Raymond Williams Society. ISSN 1369-9725. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, p. 149.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, p. 149.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, p. 151.

- ^ Marshall 2008, p. 660.

- ^ a b c d e f Pinta et al. 2017.

- ^ a b c Plasters, Bree (January 9, 2014). "Critical Analysis: The Zapatista Rebellion: 20 Years Later". Denver Journal of International Law & Policy. University of Denver Sturm College of Law. Archived from the original on June 4, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ a b Woodman, Stephen (December 2018). "From armed rebellion to radical radio". Index on Censorship. 47 (4): 73. doi:10.1177/0306422018819354. ISSN 0306-4220.

- ^ Cardozo, Mario Hurtado (2017-09-23). "Crisis de la forma jurídica y el despertar antisistémico: una mirada desde el pluralismo jurídico de las Juntas de Buen Gobierno (jbg)". IUSTA (in Spanish). 2 (47): 28. doi:10.15332/s1900-0448.2017.0047.04. ISSN 2500-5286. Archived from the original on 2023-07-23. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ Colella, Chris (Winter 2017). "The Rojava Revolution: Oil, Water, and Liberation – Commodities, Conflict, and Cooperation". Commodities, Conflict, and Cooperation. Evergreen State College. Archived from the original on 2023-07-23. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ Savran, Yagmur (2016). "The Rojava Revolution and British Solidarity". Anarchist Studies. 24 (1). Archived from the original on 2023-07-23. Retrieved 2023-07-23 – via Lawrence & Wishart.

- ^ a b Aretaios, Evangelos (March 15, 2015). "The Rojava revolution". openDemocracy. Archived from the original on 2017-02-21. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ "United Explanations – What is municipalism and why is it gaining presence in Spain?". 18 January 2016. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Davies, Jonathan S. (24 March 2021). Between Realism and Revolt: Governing Cities in the Crisis of Neoliberal Globalism. Bristol University Press. p. 27, 129, 139. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1jf2c6b. ISBN 978-1-5292-1093-4.

a heterodox array of egalitarian anti-austerity forces re-emerged across Europe and the USA, including "new municipalist" currents (Russell, 2019; Thompson, 2020). These currents... have been influenced mainly by network-theoretical ideas linked to Anarchist, Altermondialiste and libertarian socialist traditions, in which solidarity is anchored by affinity (Day, 2005)... These themes have continued to influence struggles for the past 20 years, including anti-austerity movements and new municipalisms in which anarchist and libertarian socialist traditions ally uneasily with institutionalist and state-friendly variants of democratic socialism (Taylor, 2013; Barcelona en Comú, 2019).

- ^ "Interview: The anarchists of Chile". Freedom News. 8 January 2019. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "Partidos, movimientos y coaliciones: Partido Convergencia Social" (in Spanish). Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. 2020. Archived from the original on 2024-03-04. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ The Economist (12 March 2022). "A new group of left-wing presidents takes over in Latin America". The Economist. Archived from the original on 13 September 2024. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

WHEN GABRIEL BORIC, who is 36 and calls himself a "libertarian socialist", is sworn in as Chile's president on March 11th it will mark the most radical reshaping of his country's politics in more than 30 years.

- ^ Boric, Gabriel (21 January 2022). "No espero que las élites estén de acuerdo conmigo, pero sí que dejen de tenernos miedo". BBC News Mundo (Interview) (in Spanish). Interviewed by Andrea Vial Herrera. Santiago de Chile. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

Yo provengo de la tradición socialista libertaria americanista chilena.

- ^ "Can a rise of leftist leaders bring real change to Latin America?". Al Jazeera. 23 March 2022. Archived from the original on 12 April 2024. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

Boric, who considers himself a libertarian-socialist

- ^ Long 1998, p. 306.

- ^ Pinta & Berry 2012, pp. 295–296; Ojeili 2001, p. 393.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, p. 392n1; Ojeili 2001, p. 393.

- ^ Ojeili 2001, p. 393.

- ^ Affairs, Current (31 May 2023). "Introducing Murray Bookchin, the Extraordinary Originator of 'Social Ecology'". Current Affairs. Archived from the original on 10 September 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Leval, Gaston (1959). "Libertarian Socialism: A Practical Outline" Archived 2019-08-08 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 22 August 2020 – via The Anarchist Library.

- ^ Stevenson, Nick (27 September 2016). "E. P. Thompson and Cultural Sociology: Questions of Poetics, Capitalism and the Commons" (PDF). Cultural Sociology. 11 (1). SAGE Publications: 11–27. doi:10.1177/1749975516655462. ISSN 1749-9755.

- ^ Roos, Jerome (2020-09-04). "The anarchist: How David Graeber became the left's most influential thinker". New Statesman. Retrieved 2025-03-14.

- ^ a b c Löwy, Michael; Besancenot, Olivier (2018). "Expanding the horizon: for a Libertarian Marxism". Global Discourse. 8 (2): 1–2. doi:10.1080/23269995.2018.1459332. S2CID 149816533. Archived from the original on 2022-11-13. Retrieved 2022-11-19.

- ^ Price, Wayne (2004). "Libertarian Marxism's Relation to Anarchism". The Utopian. 4: 75–76. Archived from the original on 2023-03-07. Retrieved 2022-11-19.

- ^ Ojeili 2001.

- ^ a b Carpenter, L. P. (1973). G. D. H. Cole. Cambridge [Eng.]: CUP Archive. ISBN 0-521-08702-3.

In his conversion to socialism as Morris had described it, Cole entered the socialist movement on the libertarian wing.[p.11]... Guild Socialism was an important restatement of the libertarian features of British socialism.[p.45]... [Cole] occasionally called himself a Marxist, within this humanistic, empiricist interpretation. Cole could accept this kind of Marxism because Marx's philosophy of history contains basic insights reached independently by libertarian British socialists from their own experience. The Marxism he set forth in The Meaning of Marxism was really the common sense of the British Labour movement.[p.227

- ^ Bowie, Duncan (2022). Twentieth Century Socialism in Britain. Socialist History Society. ISBN 978-1-9163423-5-4.

Henderson [formerly in the Socialist League and later in the ILP] was a libertarian socialist and was also closed to a number of anarchists, including Fred Charles and Charles Mowbray who were also active in the Norwich socialist movement.[p.12]... Russell was pluralist in his politics but can best be described as a libertarian socialist and pacifist, conviction he retained throughout his life.[p.17]... Pankhurst adopted an antiparliamentary position and collaborated with other libertarians including her partner, the Italian anarchist, Sylvio [sic] Corio.[p.23]... Beyond The Fragment [adopted] a pluralist libertarian socialist approach...[p.59]

- ^ Goodway, David (1 October 2006). Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow: Left-Libertarian Thought and British Writers from William Morris to Colin Ward. Liverpool University Press. doi:10.5949/liverpool/9781846310256.003.0002. ISBN 978-1-84631-025-6.

- ^ Bowie, Duncan (13 June 2018). "Common Wealth Manifesto, 1943". Chartist. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

Its programme of common ownership echoed that of the Labour Party but stemmed from a more idealistic perspective, later termed "libertarian socialist". It came to reject the State-dominated form of socialism adopted by Labour under the influence of Sidney and Beatrice Webb, increasingly aligning itself instead with co-operative, syndicalist and guild socialist traditions.

- ^ Taylor, Antony; Enderby, John (15 March 2021). "From 'flame' to embers? Whatever happened to the English radical tradition c.1880-2020?" (PDF). Cultural and Social History. 18 (2): 243–264. doi:10.1080/14780038.2021.1893922. ISSN 1478-0038. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 July 2024. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

During the 1940s, the radical tradition was pushed to the margins... The spirit of libertarian socialism opposed to the statism of Labour was very apparent in this strain of politics, especially in the public utterances of Sir Richard Acland, and the new Common Wealth party.[pp.249-50]

- ^ Goodway, David. "G.D.H. Cole: A Libertarian Trapped in the Labour Party". Socialist History Society. Archived from the original on 11 September 2024. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ a b Hain, Peter (July 2000). "Rediscovering our libertarian roots". Chartist. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ Goodway, David (2016). "G.D.H. Cole: A Socialist and Pluralist". Alternatives to State-Socialism in Britain. Palgrave Studies in the History of Social Movements. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 245–270. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-34162-0_9. ISBN 978-3-319-34161-3.

ole continued to identify himself as a Guild Socialist: that is, he was a socialist pluralist, or libertarian socialist, and, perhaps surprisingly, sympathetic to anarchism.

- ^ Barry, Peter Brian (16 August 2023). "George Orwell and Left-Libertarianism". George Orwell. Oxford University PressNew York. pp. 189–217. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197627402.003.0007. ISBN 978-0-19-762740-2.

- ^ Woodcock, George (1984). The crystal spirit: A study of George Orwell. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8052-0755-2. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

[George] Orwell appeared on the platform with Herbert Read, Fenner Brockway and a few other leaders of the libertarian Left.[p.18]... Julian Symons was substantially correct when he said, in his London Magazine article, that Orwell retained his faith in libertarian socialism until his death, but that in the end this belief 'was expressed for him more sympathetically in the personalities of unpractical Anarchists than in the slide rule Socialists who made up the bulk of the British Parliamentary Labor Party'.[p.27]... Orwell's affinities were...with William Morris, another libertarian Socialist who distrusted doctrinaires.[p.83]

- ^ Morgan, Kenneth O. (22 August 2015). "Historian looks at Labour favourite's prospects of leading from the left". Daily Record. Archived from the original on 10 September 2024. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

Foot also was a distinctly libertarian socialist

- ^ Rowlands, Carl (18 February 2012). "Securing a legacy for Michael Foot". LabourList. Archived from the original on 11 September 2024. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

Michael Foot is well recognised as a libertarian socialist.

- ^ Bowie, Duncan (12 April 2020). "Tony Benn: Arguments for Socialism (1979)". Chartist. Archived from the original on 10 September 2024. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

Interested in the history of ethical socialism, having been sympathetic to the wartime Common Wealth party in his youth, Benn became interested in a more libertarian socialist approach, supporting the syndicalist Institute for Workers Control and the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders workers cooperative of 1975 and advocating industrial democracy.

- ^ "the establishment radical". BBC News. 10 January 2002. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Carl Packman (29 January 2012). "Book Review: Outside In by Peter Hain". British Politics and Policy at LSE. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Passmore, Biddy (15 May 1998). "No more fire, but plenty of spark; Interview: Peter Hain". Tes Magazine. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Hain, Peter (1995). Ayes to the Left: A Future for Socialism. Lawrence and Wishart. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-85315-832-5.

- ^ Evarist Bartolo (27 April 2008). "Why I am a libertarian socialist". MaltaToday. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Chris Smith said in 2005 that in recent years Cook had been setting out a vision of "libertarian, democratic socialism that was beginning to break the sometimes sterile boundaries of 'old' and 'New' Labour labels."."Chris Smith: The House of Commons was Robin Cook's true home". Commentators, Opinion. The Independent. London. 2005-08-08. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, p. 137.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Long 1998, p. 330.

- ^ Long 1998, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Long 1998, pp. 318–319.

- ^ a b Long 1998, p. 319.

- ^ Hahnel 2005, pp. 146–148.

Bibliography

[edit]- Berry, David (2012). "The Search for a Libertarian Communism: Daniel Guérin and the 'Synthesis' of Marxism and Anarchism". In Prichard, Alex; Kinna, Ruth; Pinta, Saku; Berry, Dave (eds.). Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 187–209. ISBN 978-0-230-28037-3.

- Boraman, Toby (2012). "Carnival and Class: Anarchism and Councilism in Australasia during the 1970s". In Prichard, Alex; Kinna, Ruth; Pinta, Saku; Berry, Dave (eds.). Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 251–274. ISBN 978-0-230-28037-3.

- Cornell, Andrew (2012). "'White Skin, Black Masks': Marxist and Anti-racist Roots of Contemporary US Anarchism". In Prichard, Alex; Kinna, Ruth; Pinta, Saku; Berry, Dave (eds.). Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 167–186. ISBN 978-0-230-28037-3.

- Hahnel, Robin (2005). "Libertarian Socialism: What Went Wrong?". Economic Justice and Democracy: From Competition to Cooperation. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93344-7 – via Google Books.

- Kinna, Ruth; Prichard, Alex (2012). "Introduction". In Prichard, Alex; Kinna, Ruth; Pinta, Saku; Berry, Dave (eds.). Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-0-230-28037-3.

- Long, Roderick T. (1998). "Toward a Libertarian Theory of Class" (PDF). Social Philosophy and Policy. 15 (2): 303–349. doi:10.1017/S0265052500002028. S2CID 145150666. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-08. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- Marshall, Peter H. (2008) [1992]. Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. London: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1. OCLC 218212571.

- Ojeili, Chamsy (November 2001). "The "Advance Without Authority": Post-modernism, Libertarian Socialism, and Intellectuals". Democracy & Nature. 7 (3). Taylor & Francis: 391–413. doi:10.1080/10855660120092294. ISSN 1469-3720. Archived from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- Pinta, Saku; Berry, David (2012). "Towards a Libertarian Socialism for the Twenty-First Century?". In Prichard, Alex; Kinna, Ruth; Pinta, Saku; Berry, Dave (eds.). Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 294–303. ISBN 978-0-230-28037-3.

- Pinta, Saku; Kinna, Ruth; Prichard, Alex; Berry, David (2017). "Preface". In Prichard, Alex; Kinna, Ruth; Pinta, Saku; Berry, David (eds.). Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red (2nd ed.). Oakland, California: PM Press. ISBN 978-1-62963-390-9. LCCN 2016959590.

- Vrousalis, Nicholas (April 2011). "Libertarian Socialism: A Better Reconciliation between Equality and Self-Ownership". Social Theory & Practice. 37 (2). Florida State University: 211–226. ISSN 2154-123X. JSTOR 23558541.

Further reading

[edit]- Chomsky, Noam (1988). Otero, Carlos P. (ed.). Language and Politics. Montreal: Black Rose Books. ISBN 0-921689-35-7. OCLC 22007051.

- Dawson, Matt (2013). Late modernity, individualization and socialism: An Associational Critique of Neoliberalism. Palgrave MacMillan. doi:10.1057/9781137003423. ISBN 978-1137003423.

- Goodway, David (2006). Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 1-84631-025-3.

- Cole, G. D. H. (2020-11-16). Towards a Libertarian Socialism. AK Press. ISBN 978-1-84935-389-2.

- Guérin, Daniel (1970). Anarchism: From Theory to Practice. Translated by Klopper, Mary. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 0-85345-175-3. LCCN 71-105316.

- Hahnel, Robin (2012). "The Economic Crisis and Libertarian Socialists". In Shannon, Deric; Nocella, Anthony J.; Asimakopoulos, John (eds.). The Accumulation of Freedom: Writings on Anarchist Economics. AK Press. pp. 159–177. ISBN 978-1-84935-094-5. LCCN 2011936250.

- Hirsch, Steven J.; van der Walt, Lucien (2010a). "Rethinking Anarchism and Syndicalism: the colonial and postcolonial experience, 1870–1940". In Hirsch, Steven J.; van der Walt, Lucien (eds.). Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, 1870–1940. Studies in Global Social History. Vol. 6. Leiden: Brill. pp. xxxi–lxxiii. ISBN 978-9004188495. OCLC 868808983.

- Hirsch, Steven J.; van der Walt, Lucien (2010b). "Final Reflections: the vicissitudes of anarchist and syndicalist trajectories, 1940 to the present". In Hirsch, Steven J.; van der Walt, Lucien (eds.). Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, 1870–1940. Studies in Global Social History. Vol. 6. Leiden: Brill. pp. 395–412. ISBN 978-9004188495. OCLC 868808983.

- Levy, Carl (2012). "Antonio Gramsci, Anarchism, Syndicalism and Sovversivismo". In Prichard, Alex; Kinna, Ruth; Pinta, Saku; Berry, Dave (eds.). Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 96–115. ISBN 978-0-230-28037-3. Archived from the original on 2024-03-09. Retrieved 2024-09-10.

- Masquelier, Charles (2014). Critical Theory and Libertarian Socialism: Realizing the Political Potential of Critical Social Theory. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4411-1928-5.

- Mclaverty, Peter (2005). "Socialism and libertarianism". Journal of Political Ideologies. 10 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1080/13569310500097349. S2CID 144693867.

- Price, Wayne (2012). "The Anarchist Method: An Experimental Approach to Post-Capitalist Economies". In Shannon, Deric; Nocella, Anthony J.; Asimakopoulos, John (eds.). The Accumulation of Freedom: Writings on Anarchist Economics. AK Press. pp. 313–325. ISBN 978-1-84935-094-5. LCCN 2011936250.

- Shannon, Deric; Nocella, Anthony J.; Asimakopoulos, John, eds. (2012). "Anarchist Economics: A Holistic View". The Accumulation of Freedom: Writings on Anarchist Economics. AK Press. pp. 11–39. ISBN 978-1-84935-094-5. LCCN 2011936250.

- van der Walt, Lucien; Schmidt, Michael (2009). Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-904859-16-1. LCCN 2006933558. OCLC 1100238201.

External links

[edit] Media related to Libertarian socialism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Libertarian socialism at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch