Life in Philadelphia

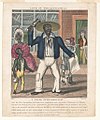

Life in Philadelphia was a series of satirical cartoons drawn and engraved by Edward Williams Clay between 1828 and 1830. He modeled them after the British series Life in London (1821), by George and Robert Cruikshank. The Cruikshank cartoons had mocked supposed class differences; Clay's cartoons mocked supposed racial differences.[1]

The cartoons were highly popular, and were copied by artists in New York and London.[2] Life in Philadelphia perpetuated a racist stereotype of hyper-elegant blacks, that became a standard trope of minstrel shows in the mid- to late-nineteenth century.[3]

Background

[edit]Edward Williams Clay was a Philadelphia lawyer and fashion illustrator, who became the most prolific political cartoonist of the Jacksonian Era.[4]

The first edition of Life in Philadelphia was published by William Simpson and Susan Hart in Philadelphia, and consisted of fourteen cartoons.[3] Simpson published the first eleven in 1828 and 1829, and Hart the last three in 1829 and 1830.[2] The engraved images were small, about 4 in (10 cm) by 3 in (7.6 cm), and printed on 6.25 in (15.9 cm) by 5.75 in (14.6 cm) sheets.[5] Hart reprinted the entire 14-cartoon series as color aquatints in 1830.[2] She also published other Clay cartoons, that later were added to the London editions of Life in Philadelphia.[2]

Four cartoons in the original series depicted only whites and nine depicted only blacks. They interacted only in Plate 11, depicting a middle-aged black woman inquiring of a young white French shopkeeper about purchasing "flesh coloured silk stockings."[2] Clay's lampoons of white Philadelphians were gentle, and depicted a promenade in the park, a costume ball, an awkward courtship between staid Quakers, and an absurdly dressed woman being mistaken for a prostitute.[3] Clay's lampoons of black Philadelphians were more biting, and ridiculed the supposed fancy dress, pretentious manners, snobbery, and malaprop-filled "black speech" of the city's small but visible black middle class.[6] "The cartoons were so popular that the term Life in Philadelphia became a standard phrase to refer to fashions, trends, and—most especially—black Philadelphians' social practices and sartorial choices."[1]: 137

Clay's cartoons were indicative of both the white supremacy and class insecurity of the Jacksonian Era,[7] a time when abolitionism and free blacks were perceived as threats to both American slaveholders and the white working class.[8]

Although no complete copy of the first edition of Life in Philadelphia is known to exist, the Library Company of Philadelphia holds examples of all fourteen cartoons, ten of them from the first edition.[5]: 86–87

London editions

[edit]Harrison Isaacs published the first London edition of Life in Philadelphia, c.1831.[9] He hired artist William Summers to redraw Clay's cartoons, enlarging the images by about 50%.[5] Summers improved them by adding depth and detail, and by placing each within a rectangular border.[5] Eleven cartoons from the original series were redrawn and enlarged, two of them depicting only whites, and Isaacs expanded the series with Summers's own cartoons, depicting only blacks.[2] The cartoons were engraved by Summers and Charles Hunt; and printed by Isaacs, and later by Gabriel Shear Tregear and others.[2]

"While the successful transfer of Clay's cartoons was attributable in part to the shared cultural backgrounds and common understandings of London and Philadelphia, the London cartoons took on a new meaning and form. London artists like Isaacs, Summers, Hunt, and Tregear made changes that signposted shifts in the cartoons' meanings, exaggerated the features of Philadelphian blacks even more grotesquely than had Clay, rendering them more bestial in anatomy and features."[1]: 145

Isaacs later removed the two cartoons depicting only whites from the series, and replaced them with other Clay cartoons depicting blacks. A cartoon depicting African Americans celebrating the 1808 end of the Slave Trade was added to coincide with the 1833 abolition of slavery in the British colonies.[2] This was credited as: "Drawn & Eng'd by I. Harris," but scholars now attribute it to Clay.[2] By the end of 1833, all twenty cartoons in the London edition depicted African Americans.[5]

The twenty African-American cartoons were reprinted in 1834, in Tregear's Black Jokes: being a Series of Laughable Caricatures on the March of Manners Amongst the Blacks.[10] The twenty cartoons were reprinted in 1860, by publishers T. C. Lewis & Co., London.[9]

The Library Company of Philadelphia holds a large collection of Life in Philadelphia cartoons, from both the Philadelphia and London editions.[2]

Original series

[edit]| Plate | Image | Artist | Publisher | Year | Captions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | Edward W. Clay | William Simpson, Philadelphia | 1828 | "Promenade in Washington Square." | [1] Not part of the London editions[1] |

| 2 | Edward W. Clay | William Simpson, Philadelphia | 1828 | "Behold, thou art fair Deborah, thou hast doves eyes. Behold thou art fair Deborah, yea pleasant!" "Turn away thine eyes from me, Timothy, for they overcome me; thy hair is as a flock of goats that appear from Gilhead!" | [2] Redrawn as Isaacs-11 | |

| 3 |  | Edward W. Clay | William Simpson, Philadelphia | 1828 | "Is Miss Dinah at home?" "Yes sir but she bery petickly engaged in washing de dishes." "Ah! I'm sorry I cant have the honour to pay my devours to her. Give her my card." | [3] Redrawn as Tregear-17 |

| 4 |  | Edward W. Clay | William Simpson, Philadelphia | 1828 | "How you find yourself dis hot weader Miss Chloe?" "Pretty well I tank you Mr. Cesar only I aspire too much!" | [4] Redrawn as Tregear-8 |

| 5 |  | Edward W. Clay | William Simpson, Philadelphia | 1828 | "Shall I hab de honour to dance de next Quadrille wid you, Miss Minta?" "Tank you Mr. Cato,—wid much pleasure, only I'm engaged for de nine next set!" | [5] Redrawn as Tregear-16 |

| 6 |  | Edward W. Clay | William Simpson, Philadelphia | 1828 | "Well brudder what 'fect you tink Morgan's deduction gwang to hab on our siety of free masons?" " 'Pon honour I tink he look rader black, 'fraid we lose de 'lection in New York!" | [6] Not part of the London editions[1] |

| 7 |  | Edward W. Clay | William Simpson, Philadelphia | 1828 | "Hurrah! Hurrah for General Jackson!!" "What de debil you hurrah for General Jackson for?—you black Nigger!—I'll larn you better.—I'm a 'ministration Man!!" | [7] Redrawn as Tregear-15 |

| 8 |  | Edward W. Clay | William Simpson, Philadelphia | 1828 | "Good evening Miss, shall I have the pleasure of walking with you?" "Me sir!! for whom do you take me, sir?" "Come, come that's a good one!—for whom do I take you? Why for myself, to be sure!" | [8] Redrawn as Isaacs-8 |

| 9 |  | Edward W. Clay | William Simpson, Philadelphia | 1829 | "How you like de new fashion shirt, Miss Florinda?" "I tink dey mighty eligum—I see you on new year day when you carry de colour on de Abolition 'siety—you look just like Pluto de God of War!" | [9] Redrawn as Tregear-18 |

| 10 | Edward W. Clay | William Simpson, Philadelphia | 1829 | "Fancy Ball" | [10] Not part of the London editions[1] | |

| 11 |  | Edward W. Clay | William Simpson, Philadelphia | 1829 | "Have you any flesh coloured silk stockings, young man?" "Oui Madame! here is von pair of de first qualité!" | [11] Redrawn as Tregear-9 with image reversed |

| 12 |  | Edward W. Clay | Susan Hart & Son, Philadelphia | 1829 | "Take away, take away dose rosy lips, Rich, rich in balmy treasure!— Turn away, turn away dose eyes ob lub, Less I die wid pleasure!!!" "Dat is bery fine, Mr. Mortimer,—you sing quite con a moor, as de Italians say!!" | [12] Redrawn as Tregear-19 |

| 13 |  | Edward W. Clay | Susan Hart & Son, Philadelphia | 1829 | "How you like de Waltz, Mr. Lorenzo?" " 'Pon de honour ob a gentleman I tink it vastly indelicate,—Only fit for de common people!!" | [13] Redrawn as Tregear-20 |

| 14 |  | Edward W. Clay | Susan Hart, Philadelphia | 1830 | "What you tink of my new poke bonnet, Frederick Augustus?" "I don't like him no how, 'case dey hide you lubly face, so you can't tell one she nigger from anoder." | [14] Redrawn as Tregear-14 |

London editions

[edit]| NOTES | |

|---|---|

| Unshaded Cartoons | Printed in the c.1831 first London edition of Life in Philadelphia by publisher Harrison Isaacs. |

| Blue-shaded Cartoons | Added to subsequent London editions by Isaacs. |

| Orange-shaded Cartoons | Added to publisher G. S. Tregear's 1833 reprinting of Life in Philadelphia. |

| Plate Numbers | Tregear's plate numbers are used for the first 20 cartoons, because his numbers remained constant. Isaacs's plate numbers changed, as he added and removed cartoons from the series. |

| Plate | Image | Artist | Publisher | Year | Captions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tregear-1 |  | William Summers | G. S. Tregear, London | c.1833 | "Dark Conversation." "Bery Black looking day dis Mons'r." "Yes Bery stormy. De Blacks flying about so make it Petickly Disagreable." | [15] |

| Tregear-2 | William Summers | G. S. Tregrear, London | c.1833 | "An Unfair Reflection." "It was bery Unfair ob Mifs Carolina to Reflect on de Palenefs ob my Complexion. I consider dat I hab got a bery Good Color." | [16] | |

| Tregear-3 |  | William Summers | G. S. Tregear, London | c.1833 | "The New Shoes." | [17] |

| Tregear-4 |  | William Summers | G. S. Tregear, London | c.1833 | "The Lub Letter." | [18] |

| Tregear-5 |  | William Summers | G. S. Tregear, London | c.1833 | "A Black Charge." "Please y-'r Worship I hab taken up dis Nigger!! case he-'s -nebriated and -sulting to de Fair sec." | [19] |

| Tregear-6 |  | William Summers | G. S. Tregear | c.1833 | "The Valentine." "Holl'a! What's all dis about— 'De rose is Red de Violets blue' 'De Debil's Black and so are You.' Well dat's bery Fair indeed." | [20] |

| Tregear-7 |  | William Summers | W. H. Isaacs, London | c.1833 | "A Black Tea Party." | [21] |

| Tregear-8 |  | unidentified (after Edward W. Clay) | Harrison Isaacs, London | c.1831 | "How you find yourself dis hot Weader Mifs Chloe?" "Pretty well tank you Mr. Cesar only I aspire too much!" | [22] Plate 3 in the first London edition |

| Tregear-9 |  | unidentified (after Edward W. Clay) | Harrison Isaacs, London | c.1831 | "Have you any Flesh coloured Silk Stockings, young man?" "Oui Madame! here is von pair of de first qualité!" | Reversed image of Plate 11 in the original series [23] |

| Tregear-10 |  | William Summers | Harrison Isaacs, London | c.1833 | "A Black Ball. La Pastorelle." "What a figure Bruder Brutus look cutting him capers dare by himself." | [24] |

| Tregear-11 |  | I. Harris (Edward W. Clay) | W. H. Isaacs, London | 1833 | "Grand Celebration Ob De Bobalition Ob African Slabery." | [25] The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act ended slavery in the British colonies. |

| Tregear-12 |  | William Summers | W. H. Isaacs, London | c.1833 | ROMEO._"How Silber sweet, sounds Lubbers Tongues by Night; like sorptest Music to attending Ears." JULIET._"Dou know'st de mask ob night is on my face, else would a maiden blush bepaint my cheek." | [26] |

| Tregear-13 |  | William Summers | W. H. Isaacs, London | c.1833 | "A Crier Extraordinary." | [27] |

| Tregear-14 |  | unidentified (after Edward W. Clay) | W. H. Isaacs, London | c.1831 | "What you tink of my new poke Bonnet, Frederich Augustus?" "I don't like him no how, 'case dey hide you Lubly Face, so you can't tell one She Nigger from anoder." | [28] |

| Tregear-15 |  | unidentified (after Edward W. Clay) | Harrison Isaacs, London | c.1831 | "Hurrah! Hurrah for General Jackson!!" "What de debil you hurrah for General Jackson for?—you black Nigger!—I'll larn you better.—I'm a 'ministration Man!!" | [29] Plate 5 in the first London edition |

| Tregear-16 |  | unidentified (after Edward W. Clay) | Harrison Isaacs, London | c.1831 | "Shall I hab de honour to dance de next Quadrille wid you, Mifs Minta?" "Tank you Mr. Cato,—wid much pleasure, only I'm engaged for de nine next set!" | [30] Plate 6 in the first London edition |

| Tregear-17 |  | unidentified (after Edward W. Clay) | Harrison Isaacs, London | c.1831 | "Is Mifs Dinah at home?" "Yes sir but she bery petickly engaged in washing de dishes." "Ah! I'm sorry I can't have the honour to pay my devours to her. Give her my card." | [31] Plate 11 in the first London edition |

| Tregear-18 |  | William Summers (after Edward W. Clay) | Harrison Isaacs, London | c.1831 | "How you like de new fashion shirt, Mifs Florinda?" "I tink dey mighty eligum—I see you on new year day when you carry de colour on de Abolition 'siety—you look just like Pluto de God of War!" | [32] Plate 9 in the original series; Plate 9 in the first London edition |

| Tregear-19 |  | unidentified (after Edward W. Clay) | Harrison Isaacs, London | c.1831 | "Take away, take away dose rosy lips, Rich, rich in balmy treasure!— Turn away, turn away dose eyes ob lub, Lefs I die wid pleasure!!!" "Dat is bery fine, Mr. Mortimer,—you sing quite con a moor, as de Italians say!!" | [33] Plate 2 in the first London edition |

| Tregear-20 |  | unidentified (after Edward W. Clay) | Harrison Isaacs, London | c.1831 | "How you like de Waltz, Mr. Lorenzo? I bery fond of it." " 'Pon de honour ob a gentleman I tink it vastly indelicate, only fit for de common people!! I wonder how de fair sec can admire it.—" | [34] Plate 13 in the first London edition |

| Isaacs-8 | William Summers (after Edward W. Clay) | Harrison Isaacs, London | c.1831 | "Good evening Mifs, shall I have the pleasure of walking with you?" "Me Sir!! for whom do you take me, Sir?" "Come, that's a good one!—for whom do I take you? why for myself to be sure!" | [35] Plate 8 in the original series; Plate 8 in the first London edition; not reprinted in Tregear. | |

| Isaacs-10 | H. Harrison (after Edward W. Clay) | W. H. Isaacs, London | c.1833 | "Life in Philadelphia." "Sketches of Character." "At Home." "Abroad." | [36] Not part of the original series or the first London edition. Self-published by Edward W. Clay, Philadelphia, 1830. Two images printed on a single sheet Added to London edition, c.1833; reprinted in Tregear, 1834. | |

| Isaacs-11 | William Summers (after Edward W. Clay) | Harrison Isaacs, London | c.1831 | "Behold, thou art fair Deborah, thou hast doves eyes. Behold thou art fair Deborah, yea pleasant!" | [37] Plate 2 in the original series; Plate 11 in the first London edition; not reprinted in Tregear. Replaced c.1833, by a cartoon about the abolition of slavery in the British colonies.[1] | |

| Isaacs-? |  | Unidentified (after Edward W. Clay) | W. H. Issacs, London | c.1832 | "The Cut Direct. or How to get up in the World." | [38] Not part of the original series or the first London edition. Published by Susan Hart, Philadelphia, 1829, as "A Dead Cut." Added to London edition, c.1832; reprinted in Tregear, 1834.[1] |

| Isaacs-? | unidentified | W. H. Isaacs, London | c.1835 | "Life in Philadelphia." "General Order!! Tention!!" "Philadelphia_Uly 14_1825_& little arter_" "That is de day ob de grand Celebrashun_" | [39] |

Related works

[edit]| Title | Image | Artist | Publisher | Year | Captions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Lessons in Dancing: Pat Juba - African Fancy Ball" |  | "Dilettante" (Edward W. Clay) | R. H. Hobson, Philadelphia | 1828 | [40] Pattin' Juba is a traditional dance with origins in Africa. Redrawn and published as "Back to Back," c.1829 | |

| "Back to Back" |  | "Dilettante" (Edward W. Clay) | R. H. Hobson, Philadelphia | c.1829 | "I reckon I've cotched de figure now!" | [41] |

| "A Dead Cut" |  | Edward W. Clay | Susan Hart, Philadelphia | 1829 | "Lord 'a marcy why Cesar is dis you, why when you 'rive from New York?" "You must be mistaking in de person black man!" "What does the imperdent nigger mean my love?" | [42] Redrawn as "The Cut Direct" and added by Isaacs to the London edition, c.1832 |

| "Sketches of Character" | Edward W. Clay | E. W. Clay, Philadelphia | 1830 | "At Home." "Abroad." | [43] Two images printed on a single sheet Redrawn and added by Isaacs to the London edition, c.1833 | |

| "Like Master, Like Man" |  | Edward W. Clay | C. P. Harrison, Philadelphia | c.1830 | ||

| "Life in New York: The Rivals" |  | Edward W. Clay | Anthony Imbert, New York | c.1830 | "Shall I hab the honour of glanting you to the battery this afternoon, Mifs Dinah, hope you'll squooze the brupt inbitation, as ..." "O you allready squoozed Mr. Sancho, only I made a privyous gagement to Mr. Romio." "Hope you not going to break your gagement to me, I hab been standing here for three hours." | [44] Redrawn and published by Charles Ingrey, London, c.1835 |

| "Mr. T. Rice as the Original Jim Crow" |  | Edward W. Clay | E. Riley, New York | c.1832 | ||

| "Life in New York: Taking the First Steps towards the Last Polish." | unidentified | John B. Pendelton, New York | c.1833 | "Allons Mademoiselle. Raise zé leg wis zé red ribbon - so bring him to zé ozer leg wis zé blue ribbon, hold up zé head, elevate zé bosom, hold in zé stomach and stick out behind! Tres bien, ver well –" | [45] | |

| "The Lady Patroness of Alblacks" |  | William Summers | G. S. Tregear, London | c.1834 | "Tregear's Black Jokes." | [46] |

| "Philadelphia Fashions, 1837." |  | Edward W. Clay | Henry R. Robinson, New York | 1837 | "What you look at Mr. Frederick Augustus?" "I look at dat White loafer wot looks at me, I guess he from New York." | [47] |

| "A Black Cut" |  | Edward W. Clay | James S. Baillie, New York | 1839 | "Gorramighty! My brudder Cato is dat you? Why whar you been dis tousand years and who dat dar you got wid you? Hab you gib up de shoe blacking business? Gib us a shake ob your paw?" "Black fellow my name is no longer Cato. I been chrisoned ober agin and |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Jenna B. Gibbs, Performing in the Temple of Liberty: Slavery, Theater, and Popular Culture (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014), pp. 134-139, 145.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Life in Philadelphia Collection". The Library Company of Philadelphia. World Digital Library. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Clay's Life in Philadelphia Cartoons". Uncle Tom's Cabin & American Culture. University of Virginia. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ^ Edward Williams Clay, Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Nancy Reynolds Davison, E. W. Clay: American Political Caricaturist of the Jacksonian Era (PhD. diss., University of Michigan, 1980), pp. 85-100.

- ^ Kenneth Finkel, Philadelphia ReVisions: The Print Department Collects (Library Company of Philadelphia, 1983), p. 22.

- ^ "Edward W. Clay and 'Life in Philadelphia'". William L. Clements Library. University of Michigan. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ "Anti-Abolitionist images". Uncle Tom's Cabin & American Culture. University of Virginia. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ^ a b Davison, Nancy R. (27–29 September 2007). E.W. Clay's Life in Philadelphia: A Moment in Time. Impressions of Philadelphia.

- ^ Jasmine Nichole Cobb, Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (New York University Press, 2015), p. 198.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch