Llywernog Mine

| Llywernog Mine | |

|---|---|

Pair of restored water wheels at Llywernog Mine | |

| Type | Silver-lead mine |

| Etymology | "The place of foxes"[1] |

| Location | Llywernog, Ceredigion, Wales |

| Coordinates | 52°24′43″N 3°51′56″W / 52.411901°N 3.8656883°W |

| First mined | 1742 |

| Restored | 1973 |

| Restored by | Peter Lloyd Harvey[1] |

| Current use | Tourist attraction and industrial heritage museum |

| Website | https://www.silvermountainexperience.co.uk |

Llywernog Mine is an 18th-century silver-lead mine in Llywernog, Ceredigion, Wales, currently run as an industrial heritage museum and tourist attraction. Exploiting the mineralised rocks of the Central Wales Orefield, it is one of many silver-lead mines in Wales, and unlike many others it still has a large number of intact buildings and mining equipment, much of which has been restored as part of the museum.

The first vein of galena, an ore which contains silver and lead, was discovered around 1742, and active mining commenced in the 1770s. Mining continued intermittently for over a century, interspersed with phases of idleness and with many changes of management. However in 1891, low lead prices forced the mine to close. The mine was briefly active again from 1907 to 1911, when zinc was extracted.

In 1974 restoration work began, and the site opened as a museum later that year.

In 2012, the site was rebranded as The Silver Mountain Experience, and included an underground horror attraction set in the mine.

Related mines

[edit]There were four mines, including Llywernog, within a one-mile radius. The other three are Powell's mine to the west of Llywernog, Clara mine to the east, and Ponterwyd mine east of Clara; but Llywernog is the only one with any visible buildings left.[2]

Another mine called the Bog, or Craignant Bach, is located to the north-east of Llywernog, and north of Ponterwyd.[3][2]

Bodcoll mine is to the south-east of Llywernog, near Devil's Bridge.[4][2]

History

[edit]

Early history (1742–1825)

[edit]The first galena vein was discovered around 1742.[5] The site was leased to Lewis Morris by D. Jones in 1749, but there is no evidence of work at the mine before Morris' death in 1765.[1] No lease records can be found until October 1, 1789, when Margaret Pyrse leased the mine to John Pierce, William Poole, and John Jones.[1][2]

Mining likely begun in the 1770s, after the construction of a turnpike road which made ore transport by pony easier.[6] By 1791 there were 60 employed miners.[2][1] At this time, there was at least one water wheel, called the "engine", and jobs included deepening the main shaft, pumping water, mining and raising ore, cutting ground, and making preparations for the engine.[2]

By 1795 there were at least two water wheels in operation,[2] but work stopped in summer 1795 due to water shortages.[1]

Around 1810 another water wheel was constructed for draining the mine. At this time the mine was in the possession of Poole, and after this period the mine is sometimes known as "Poole's mine".[1]

A draft lease suggests that the site was leased to Michael Williams and William Williams of Scorrier House, Gwennap, Cornwall, partners of Williams, Foster, and Co.,[7][8] in 1825, who leased many other mines in Cardiganshire between 1825 and 1840. However, just two years later they tried to rescind their lease, as the price of lead had fallen to a level which made Llywernog unprofitable.[2][1]

Rheidol United Mines Company and Llywernog Mines Company (1840–1852)

[edit]The next records of the mine are from 1840, when it was being worked by William Lewis, who was trying to sell it and the nearby Powell's mine for £500, including tools, pumps, two water wheels, and twelve tons of ore. The original plan was for the mine to be run by a new company with shareholders consisting of the buyer Robert Dunkin of Llanelli, the seller Lewis, Matthew Francis who advised Dunkin on the sale, and a J.H. Shears.[2]

Dunkin also bought the Rhiwrugos (now known as Erwtomau)[9] and Nantglas mines, located a couple of miles south-west of Llywernog in the Rheidol Valley. Together with Llywernog, the three mines were all run under a single company, the Rheidol United Mines Company, managed by Lewis, Dunkin, and Francis.[2]

By 1843 Shears and Dunkin had fallen into disagreement, and Shears bought Dunkin's shares. The three mines were now in the hands of Shears, who ran them under the name Llywernog Mines Company.[2] By 1845 he had relinquished the three mines.[1]

J. Holdsworth held a take-note[clarification needed] for the mine in 1851, and took out a lease in 1852, but no records show any ore sold by his company.[2][1]

Llywernog United Mining Company (1858–1861)

[edit]In 1858 the new Llywernog United Mining Company was formed to run the Llywernog, Ponterwyd, and Bog mines.[2] Work continued at Llywernog, sinking the main shaft to 36 fathoms (216 ft) below the adit, and in early 1859 it was drained to below the 25-fathom (150 ft) level, but the 20-foot wheel was unable to drain to the bottom of the shaft. Not much work was done during this period.[2][1]

John Barton Balcombe (1861–1875)

[edit]

Balcome & Co., run by John Barton Balcombe, took over the running of the Clara mine in 1861, and Llywernog a few months later in the same year. They paid £2,000 to the Llywernog United Mining Company for Llywernog. They installed a 40-foot water wheel from Bodcoll mine to fully drain the mine. By December 1862 the mine had been drained to the 36-fathom (216 ft) level, and plans were made to sink it to 50 fathoms (300 ft).[2]

In 1863 there were 14 men working at the mine, and work continued throughout the 1860s.[2]

The Llywernog Mining Company was formed in 1868, managed by Balcombe. By summer 1869, the main shaft had been sunk to 62 fathoms (372 ft), but a lack of water to turn the wheel allowed the mine to flood back to the 40-fathom (240 ft) level. In response to this, a 16-horsepower steam engine was installed in December. The price of purchasing and transporting coal was high, so the engine was only used when the water wheels could not be run. In 1871 ponds began to be used to store water to keep the wheels running during dry periods, and this allowed the main shaft to be sunk again to its final depth of 72 fathoms (432 ft).[2]

The yield and price of lead during this period were low, leading to a new Llywernog Mining Company being floated in 1872, retaining Balcombe but replacing the mine captain. Plans were drawn up to sink the shaft to 82 fathoms (492 ft), but the existing 40-foot water wheel was already struggling with the depth. Work continued until 1873, but water began to rise in the mine again and work stopped. Some work was done from 1874, but there are no records of ore being sold after 1873. A 50-foot water wheel was constructed in 1875, powered by a 6- or 7-mile leat system.[2]

Powell Mines Company (1875–1891)

[edit]In 1875 Balcombe was imprisoned for embezzlement,[1] but work continued as an annexe of Powell's mine. By the end of the 1870s the mine was idle, but in 1882 the Powell Mines Company, run by Nicholas Bray and Evan Hanson, took over at Llywernog. Balcombe's lease from 1870 was still valid, but though the terms had been violated, mining continued. In 1886 a Deed of Revocation was served for violation of the lease, but Bray and Hanson instead paid £16 a year until it expired in 1891. Little was accomplished during this time, but the main shaft was renamed as "Hanson's Shaft", after the co-director of the company.[1][2]

Low lead prices in 1891 forced many mines, including Powell's and Llywernog, to close.[1]

Zinc mining and closure (1907–1914)

[edit]In 1907, Scottish Cardigan Mines, Ltd. leased the mine for its zinc prospects. The 50-foot wheel completely pumped out the mine and Hanson's Shaft was re-timbered, but by 1911 the price of zinc had fallen again and the mine was closed.[1]

There is record of some work done by Thomas Jenkins in 1914, but he did not have much success.[2]

The 50-foot water wheel, which could be seen from the A44,[2] was demolished in 1953 after falling into a state of disrepair.[1]

Restoration and mining museum (1973–2012)

[edit]In 1973, Peter Lloyd Harvey, Dr S. H. Harvey, and Bob Griffin formed the Mid Wales Mining Museum Ltd., and obtained a lease to develop the site. Restoration work began in 1974, and after restoring some of the mine buildings the site opened to the public as a heritage museum in August. Work continued throughout the 1970s and 1980s, restoring the buildings and mining equipment, and clearing the underground tunnels.[1]

The Silver Mountain Experience (2012–Present)

[edit]In 2012, Llywernog Mine was rebranded to The Silver Mountain Experience, which included the opening of The Black Chasm, an underground scare attraction set in the mine.[10]

Shafts, buildings, and features

[edit]Main shaft

[edit]The main mine shaft was sunk to 72 fathoms (432 ft) deep, with many levels driven during mining, from the 10-fathom level to the 72-fathom level.[2] A large part of the shaft is flooded.

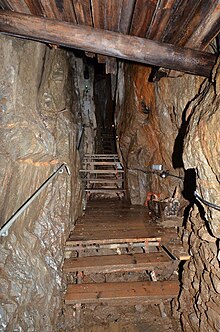

Balcombe's Level

[edit]Balcombe's Level is a tunnel to the east of the main shaft, the last prospecting adit opened by Balcombe. It was the first underground area to be cleared and made accessible to the public.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Simon S. J. Hughes (Autumn 1990). "Llywernog Mine and Museum Dyfed, Wales" (PDF). UK Journal of Mines and Minerals. No. 8. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Boyns, T. (1976). "The Mines of Llywernog". National Library of Wales Journal. XIX (4). ISSN 1758-2539.

- ^ "Cardiganshire VII.SE (includes: Cwmrheidol; Melindwr.)". Great Britain County Series, 6 inches to the mile. Ordnance Survey. 1886.

- ^ "Cardiganshire XI.NE (includes: Cwmrheidol; Llanfihangel y Creuddyn Uchaf.)". Great Britain County Series, 6 inches to the mile. Ordnance Survey. 1886.

- ^ Polsom-Jenkins, Jessica (8 August 2012). "Llywernog Silver-lead Mine, Ceredigion". Immediate Media Company Limited. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Ceredigion's rich mining heritage". BBC. 20 October 2009.

- ^ Tregidga, Garry (21 May 2009). ""Williams, John Charles (1861–1939)"". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Williams, Foster and Co". Grace's Guide - British Industrial History. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Lord, Ioan R. (2017). "Mines of the Rheidol Valley: The Erwtomau Mill". The Vale of Rheidol Railway Newsletter. No. 25. pp. 7–8. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Wales' new scare attraction, the Silver Mountain Experience, opens officially". Breaking Travel News. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch