Louis William Valentine DuBourg

Louis William Valentine DuBourg | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Besançon | |

| |

| See | Besançon |

| Installed | 10 July 1833 |

| Term ended | 12 December 1833 |

| Predecessor | Louis-François de Rohan-Chabot |

| Successor | Jacques-Marie-Adrien-Césaire Mathieu |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 20 March 1790 by Antoine-Éléonor-Léon Leclerc de Juigné |

| Consecration | 24 September 1815 by Giuseppe Doria Pamphili |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Louis-Guillaume-Valentin DuBourg 10 January 1766 |

| Died | 12 December 1833 (aged 67) Besançon, Doubs, Kingdom of France |

| Buried | Besançon Cathedral |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| Alma mater | |

| Motto | Latin: Lilium inter spinas[1] |

Louis William Valentine DuBourg PSS (French: Louis-Guillaume-Valentin DuBourg; 10 January 1766 – 12 December 1833) was a French Catholic prelate and Sulpician missionary to the United States. He built up the church in the vast new Louisiana Territory as the Bishop of Louisiana and the Two Floridas and later became the Bishop of Montauban and finally the Archbishop of Besançon in France.

Born in the colony of Saint-Domingue, DuBourg was sent to France at a young age to be educated and entered the Society of Saint Sulpice. As a cleric and son of a noble family, the French Revolution forced him into exile in Spain. In 1794, DuBourg sailed to the United States and began teaching and ministering in Baltimore, becoming the president of Georgetown College in Washington in 1795. He significantly improved the quality of the institution, but mounted a substantial debt and was ousted by the Jesuit owners of the college in 1798. DuBourg then founded a lay collegiate counterpart to St. Mary's Seminary in Baltimore. He also selected the site of Baltimore's first cathedral and became the ecclesiastical superior to Elizabeth Ann Seton's newly founded Sisters of Charity.

In 1812, DuBourg was made the apostolic administrator of the Diocese of Louisiana and the Two Floridas, and three years later, its bishop. Catholic New Orleanians rejected his authority and he was forced to move his episcopal seat to St. Louis, Missouri. There, he built the first cathedral west of the Mississippi River and established missions to the American Indians, dozens of churches, and numerous schools, including St. Mary's of the Barrens Seminary and Saint Louis University. He also recruited the Sisters of Loretto and Rose Philippine Duchesne's Sisters of the Sacred Heart to found several academies.

Never able to establish his seat in New Orleans, DuBourg returned to France in 1826, where he was made the Bishop of Montauban. Just months before his death in 1833, he became the Archbishop of Besançon.

Early life and education

[edit]Louis-Guillaume-Valentin DuBourg was born in the city of Cap-Français (known today as Cap-Haïtien) in the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue, likely on 10 January 1766.[a] Born to a noble family originally from Bordeaux, France,[4] his mother was Marguerite DuBourg née Armand de Vogluzan and his father was Pierre DuBourg, who held the titles of chevalier de la Loubère et Saint-Christaud and Sieur de Rochemont. Pierre was a licensed sea captain and highly successful merchant in the coffee trade.[5][6]

Following the death of his mother,[6] when he was two years of age,[5] DuBourg was sent to France to be educated.[7] He lived with his maternal grandparents in Bordeaux, and eventually enrolled at the College of Guienne, where he proved to be a good student.[5] Deciding that he would become a priest, DuBourg entered the Saint-Sulpice Seminary, attached to the Church of Saint-Sulpice, in 1786.[8] There, he studied under the direction of Francis Charles Nagot, who would later introduce the Society of the Priests of Saint Sulpice to the United States.[9]

In 1788,[8] Nagot selected DuBourg to be the superior of the newly established Sulpician minor seminary in Issy-les-Moulineaux, outside of Paris. At the same time, he continued his studies at the College of Sorbonne,[9] and was ordained a priest by Antoine-Éléonor-Léon Leclerc de Juigné, the Archbishop of Paris, on 20 March 1790.[5]

Exile and arrival in Maryland

[edit]DuBourg was not in Issy long before the school became the target of the French Revolution.[5] With the persecution of clerics during the Reign of Terror, he left the seminary. Five days later,[6] on 15 August 1792, it was attacked by a Jacobin mob that massacred the four remaining priests. DuBourg fled first to Bourdeaux. However, his aristocratic lineage, the presence of anti-clerical spies, and the conduct of home inspections forced him to eventually leave France.[9][5] Disguised as a traveling fiddler,[10] he escaped to Ourense, Spain.[11]

While exiled in Spain, DuBourg became fluent in Spanish.[5] The Spanish government believed French clergy were engaged in heterodox practices,[6] and restricted their ability to teach and publicly minister. Dissatisfied with these limitations, DuBourg sailed for the United States and arrived in Baltimore, Maryland, on 14 December 1794.[5] He was incardinated in the Diocese of Baltimore by Bishop John Carroll and petitioned Jacques-André Emery, the Sulpician Superior General, for admission to the order, which was by then operating in Baltimore.[12] On 9 March 1795, he became a professed member of the Society of Saint Sulpice.[5]

In Baltimore, there was a rapidly growing population of West Indians who had fled the Haitian Revolution, and French who had fled the French Revolution; in a short time, they doubled the total number of Catholics in the United States. DuBourg began ministering to these French-speaking immigrants and holding classes for their children,[5] as well as those of Spanish immigrants. By teaching these classes, DuBourg learned English, and came to be regarded as a polished and effective preacher.[4]

President of Georgetown College

[edit]In October 1795, just several months after arriving in the United States, DuBourg was appointed by Carroll to succeed Robert Molyneux as the third president of Georgetown College.[13] He was one of four Sulpicians to serve on the faculty during the founding era of the Jesuit college, who together had a significant influence on the school's development.[6] DuBourg had an ambitious vision for Georgetown, seeking to make it the best college in the United States. One historian of the university credits him with transforming Georgetown from an "academy" into a "college."[14]

Seeking to make the school more cosmopolitan,[5] DuBourg recruited many students from Baltimore, particularly French refugees from the West Indies.[15] He also admitted many non-Catholics.[16] Overall, the size of the student body grew during his tenure.[4] DuBourg solicited financial support from Catholic donors,[5] which allowed him to sponsor sixteen students throughout his tenure to study at Georgetown in preparation for the seminary. In 1797, he sponsored one potential seminarian instead of accepting a salary increase.[17] DuBourg hired 16 new teachers, greatly expanding the size of the college's faculty and raised the salary of professors. A significant departure from his predecessors, the significant majority of professors he hired were laymen, rather than clerics.[14]

In keeping with his mission to make Georgetown an elite college, DuBourg improved and expanded the curriculum by adding courses in history, moral philosophy, natural philosophy, and Spanish; music, dancing, and drawing were also taught for the first time. He instituted new features, including the college's first seal and uniforms for students. He promoted the school's public image by advertising its favorable situation upon a hill and proximity to Washington, D.C., the seat of the federal government. DuBourg became active in Washington's high society, including making the acquaintance of Thomas Law, a merchant who enrolled his son at Georgetown.[14] Through Law, DuBuissson received an invitation to dine with the former President George Washington at his home, Mount Vernon, in July 1797. The following month, Washington visited Georgetown's campus.[18][5] Around this time, DuBourg also invited a group of Poor Clares who fled the revolution in France, and they founded a school for girls in the Georgetown area in 1798.[19]

Though DuBourg's improvements elevated the college's quality, they placed Georgetown in substantial debt. Donations were inadequate to offset this debt, which was worsened by economic stagnation in Washington in the 1790s. This strained the relationship between DuBourg and the Jesuits, who were forced to sell some land in Maryland to meet the financial obligations.[18] The trustees of the Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen,[b] which owned Georgetown, elected new Jesuits to the college's board of directors and empowered the board to remove the president.[21] In October 1797, the board decided to keep DuBourg as president, but stripped him of his power over Georgetown's finances, transferring it to a new vice president, Francis Neale, who implemented strict austerity measures.[22] Motivated in part by anti-French sentiment, the Maryland Jesuits eventually took steps to oust DuBourg in 1798, leading to his resignation. He was succeeded by Francis Neale's brother, Leonard Neale, at Christmas.[23][5]

Founding St. Mary's College

[edit]Upon leaving Georgetown, DuBourg traveled to Havana, Cuba, where he joined two other Sulpicians seeking to establish a college there. However, this project faced political opposition, and DuBourg returned to Baltimore in August 1799.[24]

That year, DuBourg founded and became the first president of a college for lay students at St. Mary's Seminary.[25][3] Though DuBourg initially intended the school to be open for general education, Bishop Carroll required that admission be limited only to West Indian students, so as not to compete with Georgetown College.[26] As a result, many Cubans who had met DuBourg during his time in Havana sent their sons to be educated at St. Mary's College.[24] The Jesuits opposed the founding of St. Mary's College, and DuBourg offered to resolve the dispute by closing St. Mary's College and transferring its students and faculty to Georgetown; however, the Jesuits did not act on this proposal.[26]

In 1800, the Sulpicians lodged a protest with Carroll over the restriction on admitting only West Indian students.[26] DuBourg travelled to Cuba in 1802 to recruit students, where he was informed by the Spanish government—which feared the education of Cubans in a republican country—that Cuban students would no longer be allowed to attend school in Baltimore.[24] The following year, the Spanish Navy sent a frigate to Baltimore to demand that all Spanish nationals return.[27] Carroll then lifted the restriction on enrollment,[26] and the school began admitting students of any nationality in 1803.[28] As a result, enrollment at St. Mary's College grew rapidly, overtaking that of Georgetown.[28] Students arrived not only from the West Indies, but from South America, Mexico, and many parts of the United States.[27] The new college was chartered by the State of Maryland in 1805,[28] and was elevated to university status by the Maryland General Assembly the following year.[27]

To accommodate the prospering school, DuBourg oversaw the construction of several new buildings.[27] Among these was St. Mary's Seminary Chapel, referred to by Elizabeth Ann Seton as "Mr. DuBourg's chapel." DuBourg hired Maximilian Godefroy to design the chapel, who he had previously appointed to the faculty of St. Mary's. Work began in 1806, and DuBourg expedited the project by retaining Benjamin Henry Latrobe, the Architect of the Capitol, whose skilled Italian artists completed the building ini 1808.[5]

Diocesan ministry

[edit]

DuBourg ministered to and provided charity to the many refugees living in Baltimore who had fled Saint-Domingue during the Haitian Revolution. With John Tessier, he also established a congregation for the many poor Black Baltimoreans who met and celebrated Mass at St. Mary's Chapel. From this congregation eventually formed the Oblate Sisters of Providence. DuBourg also established a lay fraternal organization of parishioners that provided charity for the city.[29]

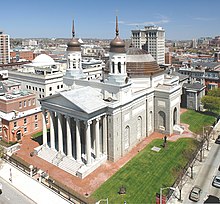

DuBourg played an important role in the construction of Baltimore's first cathedral. Bishop Carroll desired to replace St. Peter's Pro-Cathedral with a proper cathedral, and DuBourg convinced him to move it from St. Peter's to a new location. DuBourg identified a site atop a hill, which would become known as Cathedral Hill, and negotiated with the sale with the owner of the land.[30] He then raised the $23,000 necessary to purchase the land,[31] equivalent to $460,000 in 2024.[32] Construction on the cathedral began in 1806.[33]

Work with Elizabeth Ann Seton

[edit]In 1806,[4] DuBourg was in New York City to sell lottery tickets as a fundraiser for St. Mary's University, where he met the future saint Elizabeth Ann Seton, who he urged to travel to Baltimore to establish a school for girls.[34] Seton opened her school in June 1808, where women from around the country joined her. DuBourg was influential in the founding of her religious community.[35] He contributed $8,000 to establish her religious community,[36] and proposed that she adopt the rule of the French Sisters of Charity. Heeding this proposal, she established a community of the Sisters of Charity on 31 July 1809, in Emmitsburg, Maryland.[35] While Seton was the head of the organization, DuBourg functioned as their ecclesiastical superior.[37]

Before long, tensions arose between Seton and DuBourg, who forbade her from communicating with her mentor, a Sulpician priest, Pierre Babade. Seton appealed DuBourg's instruction to John Carroll,[37] who referred the matter to Nagot, the Suplician superior in the United States. In response to the dispute, DuBourg resigned as superior of Seton's religious community. Despite Seton's desire that DuBourg would remain as superior, he declined and Nagot refused to order him to return.[38]

Louisiana and the Two Floridas

[edit]| Styles of Louis William Valentine DuBourg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | The Most Reverend |

| Spoken style | Your Excellency |

| Religious style | Archbishop |

Apostolic administrator

[edit]With the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, a vast new territory became part of the United States.[5] The first bishop overseeing this territory, which spanned from the Gulf of Mexico to the Illinois Territory, was transferred to another diocese in 1801, leaving the bishopric vacant. The second bishop appointed, Francisco Porró y Reinado, never took possession of the diocese and either died or was appointed to another diocese.[39] Moreover, the vicar general died in 1804, leaving no one to oversee the diocese.[40] While Carroll and the Holy See corresponded to select a new bishop,[41] Carroll named DuBourg the apostolic administrator of the Diocese of Louisiana and the Two Floridas on 18 August 1812.[5][3]

Upon becoming administrator, DuBourg found an expansive diocese with few priests, hardly any churches, and no Catholic schools or charitable institutions.[41] Upon arriving in New Orleans, he found the local Catholic population aligned with their pastor, a Capuchin priest, Antonio de Sedella.[42] Sedella rejected the jurisdiction of Carroll, an American bishop, to appoint DuBourg as administrator over the French clergy in Louisiana.[43] Due to hostility from the locals, DuBourg was forced to reside outside of the city.[3] Meanwhile, while the Holy See eventually settled on DuBourg as the next bishop, he could not be immediately appointed.[41] Pope Pius VII had been taken prisoner by Napoleon in 1809, and then forcibly brought to France in 1812.[44] In protest of his captivity, Pope Pius refused to issue any papal bulls, including those appointing bishops.[41]

The diocese became embroiled in the War of 1812. During the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, DuBourg called on Catholics to support the Americans over the British. Following the American victory, on 23 January 1815, Major General Andrew Jackson entered the city and was escorted by DuBourg into the St. Louis Cathedral, where he was greeted with a Te Deum hymn.[5]

In order to alleviate the shortage of priests and lack of institutions, DuBourg sailed to Europe in 1815 to recruit priests and fundraise.[45] While in Rome, he was officially appointed by Pius VII as the Bishop of Louisiana and the Two Floridas.[5] He was consecrated by Cardinal Giuseppe Doria Pamphili on 24 September in the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi.[46] He would continue his recruiting in Europe for two years,[5] and while in Lyon, France, he met a widow and expressed his desire to create an organization to raise funds for the church in the vast Louisiana diocese. This eventually became the Society for the Propagation of the Faith several years later.[47]

He eventually sailed to the United States from France on 1 July 1817. He returned with five priests—including several Lazarists from Rome, among whom were Felix de Andreis and Joseph Rosati—and 26 other men from Italy and France—including Antoine Blanc—who intended to become priests or brothers.[48] DuBourg also invited the Ursuline nuns to establish a ministry in the diocese, and nine postulants accepted.[49] He arrived in Annapolis, Maryland on 4 September.[48]

Bishop of Louisiana

[edit]Upon returning to his diocese, DuBourg decided that it was not safe for him in New Orleans, and he took up residence in St. Louis, Missouri. As such, he became the first bishop to use the city of St. Louis as his episcopal see.[50] The overland journey from Maryland to St. Louis was perilous and took several weeks. He started out in a stagecoach,[51] which at one point overturned on the rough terrain, causing him to nearly fracture his skull.[42] Unable to continue by stagecoach, he finished the last five days of his journey to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on foot. From there, he traveled by boat to Louisville and Bardstown, Kentucky.[51] DuBourg finally arrived in St. Louis in January 1818, and would remain there for five years.[42]

Establishing the church in St. Louis

[edit]Unlike in New Orleans, DuBourg was warmly received by the Catholics of St. Louis.[42] Shortly after arriving, he began building up the part of the diocese in the Missouri Territory. He soon raised funds to construct churches throughout the region and staff them with priests. Among these was a grand church for St. Louis that would eventually become the cathedral of the Archdiocese of St. Louis and the first cathedral west of the Mississippi River.[42][52] DuBourg also sought to promote education in the diocese. In order to be able to train priests at home, rather than rely on a European missionaries, he established St. Mary's of the Barrens Seminary in Perryville in 1818,[42] placing it under the charge of the Lazarist fathers.[53] In August of that year, he also recruited the future saint Rose Philippine Duchesne and her religious order from France, the Society of the Sacred Heart, to open schools for girls on the frontier.[8][42] They founded the Academy of the Sacred Heart in St. Charles as the first free school west of the Mississippi River.[5] They opened another soon thereafter in Florissant.[3] DuBourg also invited the Sisters of Loretto to establish a school for girls.[49]

In 1818, at DuBourg's instruction, the Saint Louis Academy was founded. Operating out of several rented rooms, its purpose was to educate local laymen.[54] Several years later, he requested that the Maryland Jesuits send several of their members to Missouri to staff the diocese's missions to the American Indians. The Jesuits sent several Belgian members,[53] who arrived in 1823,[42] and established a house in Florissant and began ministering to the Indians. DuBourg visited Washington, D.C. in 1823,[53] where he met the U.S. Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, who encouraged the Jesuit missions and obtained federal funding for the establishment of Indian schools.[5] On 7 January 1824, DuBourg offered the Jesuits to assume control of the academy,[55] which became known as Saint Louis College in 1820. The Jesuits accepted this offer in 1827,[56] and Peter Verhaegen became the first Jesuit president of the college, which was chartered as Saint Louis University several years later. The school's first Jesuit treasurer was Pierre-Jean De Smet, who became a famous missionary to the Indians.[5] The lower division of the academy became St. Louis University High School.[57]

In 1822, DuBourg purchased an enslaved couple and their children. He soon thereafter gifted one of the slave children to Rose Philippine Duchesne and transferred ownership of the other slaves to his successor bishop, Joseph Rosati.[58][59]

In 1823, DuBourg's time in St. Louis came to an end.[60] While he had visited New Orleans every year while his seat was in St. Louis,[3] he decided it proper to return the diocesan seat to New Orleans and requested the appointment of Rosati as his coadjutor bishop. He consecrated Rosati on 25 March 1824, and left him to oversee the church in St. Louis.[60]

DuBourg remained in New Orleans for three years, and once again met local opposition.[52] On 28 August 1825, he became the Vicar Apostolic of Mississippi, in addition to his episcopal duties.[46] He found a shortage of priests in Louisiana but faced resistance when trying to establish a seminary in New Orleans or transfer priests from other parts of the diocese. By this time, he was also weary of traveling throughout the expansive diocese.[52] Therefore, DuBourg sailed to Rome,[61] and on 26 June 1826, he resigned the bishopric. Later that year, the large diocese was split into the Diocese of New Orleans and the new Diocese of St. Louis.[5] By the end of his episcopacy, 40 new churches had been built, in addition to many schools.[8] This significant development, however, left the diocese with considerable debt.[42]

Return to France

[edit]Bishop of Montauban

[edit]Believing that he would enter retirement,[42] DuBourg returned to France on 3 July 1826.[5] However, soon thereafter, he was named to replace Jean-Louis Lefebvre de Cheverus, the first Bishop of Boston, as the Bishop of Montauban on 2 October of that year. This was possible because with the end of the French Revolution, DuBourg's clerical rights and noble rank were restored. In his writings, he wrote of his dislike for Napoleonic titles of nobility, which carried no social responsibilities, and instead supported a noblesse oblige.[5] Pursuant to the Concordat of 1801,[62] he swore an oath of allegiance to the French government before King Charles X on 13 November 1826.[5]

DuBourg found his episcopacy in France much less taxing than that on the American frontier.[43] At the time he was installed a bishop, the Diocese of Montauban had 242,000 Catholics, 353 priests, grand churches, seminaries and lay schools, and numerous religious orders operating.[63] During his seven years in Montauban, DuBourg improved education in the diocese and increased the number of scholarships for students.[5] He also dissuaded the French authorities from persecuting Catholics in the diocese during the July Revolution of 1830.[64]

Archbishop of Besançon

[edit]In February 1833, DuBourg was appointed to succeed Cardinal Louis-François de Rohan-Chabot as the Archbishop of Besançon. By this time, however, his health had deteriorated, and he visited the thermal baths of Luxeuil-les-Bains for relief. He was formally installed as bishop of the archdiocese on 10 October 1833,[64] and he received the pallium on 1 November. Though confined to his deathbed, DuBourg organized two retreats for the 900 priests of his archdiocese.[65] Two months after his installation, he died in Bensançon on 12 December 1833.[5] He was interred in the Cathédrale Saint-Jean in Besançon.[46]

Legacy

[edit]Several institutions bear the name of DuBourg. DuBourg Hall at Saint Louis University was dedicated on 10 January 1898.[55] Bishop DuBourg High School in St. Louis, Missouri, opened in 1950.[66]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Some sources identify his date of birth as 14 February or 16 February.[2][3]

- ^ The Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen was created in 1792 in response to the suppression of the Society of Jesus. Its purpose was to preserve the property of the former Jesuits with the hope that the Society would be one day restored and the property returned under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of a Jesuit superior in America.[20]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Duchesne 2001, p. 13

- ^ Clarke 1872, p. 205

- ^ a b c d e f Chambon 1909

- ^ a b c d Rice 1999, p. 258

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Burch 1999

- ^ a b c d e Curran 1993, p. 48

- ^ Clarke 1872, p. 205

- ^ a b c d Bowden 1993, p. 153

- ^ a b c Clarke 1872, p. 206

- ^ Barthel 2014, p. 117

- ^ "Bishop Louis William Valentine DuBourg" (PDF). Duchesne High School. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Clarke 1872, pp. 206–207

- ^ Curran 1993, p. 47

- ^ a b c Curran 1993, p. 49

- ^ Curran 1993, p. 38

- ^ Curran 1993, p. 54

- ^ Curran 1993, p. 39

- ^ a b Curran 1993, p. 50

- ^ Naughten 1943, pp. 66–67

- ^ Curran 2012, pp. 14–16

- ^ Curran 1993, pp. 50–51

- ^ Curran 1993, p. 51

- ^ Curran 1993, p. 52

- ^ a b c Clarke 1872, p. 207

- ^ Curran 1993, pp. 54–55

- ^ a b c d Curran 1993, p. 55

- ^ a b c d Clarke 1872, p. 208

- ^ a b c Curran 1993, p. 56

- ^ Clarke 1872, p. 210

- ^ Clarke 1872, p. 211

- ^ Clarke 1872, pp. 211–212

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Basilica History". The Baltimore Basilica. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Barthel 2014, p. 116

- ^ a b Prietto 2010, p. 31

- ^ Murray 1882, p. 358

- ^ a b Barthel 2014, p. 139

- ^ Barthel 2014, p. 140

- ^ Points 1911

- ^ Clarke 1872, p. 216

- ^ a b c d Clarke 1872, p. 217

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rice 1999, p. 259

- ^ a b Bowden 1993, p. 154

- ^ Sheehan, Edward (13 December 1981). "When Napoleon Captured the Pope". The New York Times. p. 4. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Clarke 1872, p. 220

- ^ a b c "Bishop William DuBourg Papers, 1808–1839". Archdiocese of St. Louis. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Clarke 1872, p. 228

- ^ a b Clarke 1872, p. 221

- ^ a b Clarke 1872, p. 231

- ^ "History Of The Archdiocese Of St. Louis". Archdiocese of St. Louis. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ a b Clarke 1872, p. 222

- ^ a b c "Bishop Louis DuBourg". Bishop DuBourg High School. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ a b c Clarke 1872, p. 230

- ^ "Saint Louis University History". Saint Louis University. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ a b "On this Day in SLU History". Saint Louis University. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Blakely 1912

- ^ "History". St. Louis University High School. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Lewis-Thompson, Marissanne (27 July 2021). "Two St. Louis Catholic High Schools Grapple With Namesakes' Ties To Slavery". St. Louis Public Radio. Archived from the original on 11 August 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2025.

- ^ Chicoine, Maureen; Osiek, Lyn. "Eliza Nesbit". Society of the Sacred Heart: United States and Canada. Archived from the original on 10 September 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2025.

- ^ a b Clarke 1872, p. 233

- ^ Clarke 1872, p. 234

- ^ Barbara 1926, p. 252

- ^ Clarke 1872, p. 235

- ^ a b Clarke 1872, p. 236

- ^ Clarke 1872, p. 237

- ^ "The History of Bishop DuBourg High School". Bishop DuBourg High School. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Barbara, Sr. M. (July 1926). "Napoleon Bonaparte and the Restoration of Catholicism in France". The Catholic Historical Review. 12 (2): 241–257. JSTOR 25012302.

- Barthel, Joan (2014). American Saint: The Life of Elizabeth Seton. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-57162-7. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2021 – via Google Books.

- Blakely, Paul Lendrum (1912). "University of St. Louis". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Bowden, Henry Warner (1993). Dictionary of American Religious Biography (2nd ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-27825-3. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020 – via Google Books.

- Burch, Francis F. (1999). "DuBourg, Louis William Valentine". American National Biography (online ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0800407. (subscription required)

- Chambon, Célestin M. (1909). "Louis-Guillaume-Valentin Dubourg". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company. OCLC 1017058.

- Clarke, Richard H. (1872). "Most Rev. William Louis Dubourg, D.D.". Lives of the Deceased Bishops of the Catholic Church in the United States. Vol. 1. New York: P. O'Shea. pp. 205–238. OCLC 809578529. Retrieved 18 October 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Curran, Robert Emmett (1993). The Bicentennial History of Georgetown University: From Academy to University, 1789–1889. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-0-87840-485-8. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020 – via Google Books.

- Curran, Robert Emmett (2012). "Ambrose Maréchal, the Jesuits, and the Demise of Ecclesial Republicanism in Maryland, 1818–1838". Shaping American Catholicism: Maryland and New York, 1805–1915. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. pp. 13–158. ISBN 978-0813219677. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- Duchesne, Philippine (2001). Paisant, Chantal (ed.). Les années pionnières, 1818–1823 [The Pioneer Years, 1818–1823] (in French). Paris: Éditions du Cerf. ISBN 2-204-06747-4.

- Murray, John O'Kane (1882). The Catholic Pioneers of America (New, rev. ed.). Philadelphia: H. L. Kilner & Co. OCLC 4812614. Retrieved 23 December 2020 – via HathiTrust.

- Naughten, Gabriel J. (March 1943). "The Poor Clares in Georgetown: Second Convent of Women in the United States". Franciscan Studies. New series. 3 (1): 63–72. JSTOR 23801697.

- Points, Marie Louise (1911). "Archdiocese of New Orleans". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Prietto, Carole (Spring–Summer 2010). "The Journey of the Sisters of Charity to St. Louis, 1828" (PDF). The Confluence. 2 (1): 28–41. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Rice, C. David (1999). "DuBourg, Louis William (1766–1833)". In Christensen, Lawrence O.; Foley, William E.; Kremer, Gary R.; Winn, Kenneth H. (eds.). Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. pp. 258–259. ISBN 0-8262-1222-0. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020 – via Google Books.

Further reading

[edit]- "Archbishop Louis-Guillaume-Valentin Dubourg, P.S.S." Catholic-Hierarchy.org. David M. Cheney.

- Archdiocese of St. Louis: Three Centuries of Catholicism, 1700–2000. Strasbourg: Éditions du Signe. 2001. ISBN 9782746803534. Archived from the original on 5 April 2005.

- Carmel, Mary (Winter 1963). "Problems of William Louis DuBourg, Bishop of Louisiana, 1815–1826". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 4 (1): 55–72. JSTOR 4230699.

- DeStefano, Michael T. (2016). "DuBourg's Defense of St. Mary's College: Apologetics and the Creation of a Catholic Identity in the Early American Republic". Church History. 85 (1): 65–96. doi:10.1017/S0009640715001353. S2CID 163958183.

- Melville, Annabelle M. (1986). Louis William DuBourg: Bishop of Louisiana and the Floridas, Bishop of Montauban, and Archbishop of Besançon, 1766–1833. Chicago: Loyola University Press. OCLC 571304480.

- Who Was Who in America: Historical Volume 1607–1896 (Rev. ed.). Chicago: Marquis. 1967. OCLC 5357538.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch