Ludendorff Bridge

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2016) |

Ludendorff Bridge Ludendorff-Brücke | |

|---|---|

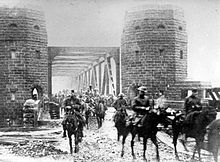

The bridge seen from the bank of the Rhine before its March 1945 collapse | |

| Coordinates | 50°34′45″N 7°14′39″E / 50.5792°N 7.2442°E |

| Carried | Railway |

| Crossed | Rhine |

| Locale | Rhineland-Palatinate |

| Official name | Ludendorff Bridge |

| Other name(s) | Bridge at Remagen |

| Named for | Erich Ludendorff |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Through arch bridge |

| Material | Iron |

| Total length | 325 m (1,066 ft) |

| Piers in water | Two |

| History | |

| Designer | Karl Wiener |

| Constructed by | Grün & Bilfinger |

| Construction start | 1916 |

| Construction end | 1919 |

| Construction cost | 2.1 million marks |

| Collapsed | 17 March 1945 |

| Location | |

| |

The Ludendorff Bridge (sometimes referred to as the Bridge at Remagen) was a bridge across the river Rhine in Germany which was captured by United States Army forces in early March 1945 during the Battle of Remagen, in the closing weeks of World War II, when it was one of the few remaining bridges in the region and therefore a critical strategic point. Built during World War I to help deliver reinforcements and supplies to German troops on the Western Front, it connected Remagen on the west bank and the village of Erpel on the east bank between two hills flanking the river.

Midway through Operation Lumberjack, on 7 March 1945, the troops of the 1st U.S. Army approached Remagen and were surprised to find that the bridge was still standing.[1] Its capture, two weeks before Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery's planned Operation Plunder, enabled the U.S. Army to establish a bridgehead on the eastern side of the Rhine. After the U.S. forces captured the bridge, German forces tried to destroy it many times.

It finally collapsed on 17 March 1945, 10 days after it was captured; 28 Army engineers were killed in the collapse while a further 63 were injured. Of those who died, 18 were actually missing, but presumably had drowned in the swift current of the Rhine.[2] The bridge, while it stood, and newly established pontoon bridges, enabled the U.S. Army to secure a bridgehead of six divisions, about 125,000 troops, with accompanying tanks, artillery pieces, and trucks, across the Rhine. Capturing the bridge hastened the war's conclusion,[3] and V-E Day came on May 8. After the war, the bridge was not rebuilt; the towers on the west bank were converted into a museum and the towers on the east bank are now a performing-arts space.

A 2020 poll of local people found that 91% favoured rebuilding the bridge; without it there is no river crossing for 44 km (27 mi), and few ferries. In 2022 plans were initiated to build a suspension bridge for pedestrians and cyclists. Local communities indicated an interest to help fund the project and an engineer was commissioned to draw up plans.[4]

History

[edit]Construction

[edit]

Remagen is located close to and south of the city of Bonn. The town of Remagen was founded by the Romans about 2,000 years earlier. It had been destroyed multiple times and rebuilt each time. Under the Schlieffen Plan, a bridge was planned to be built there in 1912, as well as bridges in Engers and Rüdesheim am Rhein.

German General Erich Ludendorff was a key advocate for building this bridge during World War I, and it was named after him.[5] It was designed by Karl Wiener to connect the Right Rhine Railway, the Left Rhine Railway and the Ahr Valley Railway (Ahrtalbahn)[6] and carry troops and supplies to the Western Front. Constructed between 1916 and 1919, using Russian prisoners of war as labour, it carried two railway lines and a pedestrian catwalk on either side.[5] Work on the bridge pillars and arches was done by leading construction companies Grün & Bilfinger[7][8] with the steel bridge built by MAN-Werk Gustavsburg.[9]

It was one of three bridges built to improve railroad traffic between Germany and France during World War I; the others were the Hindenburg Bridge at Bingen am Rhein and the Urmitz Bridge on the Neuwied–Koblenz railway near Koblenz.

Design

[edit]The railway bridge had three spans, two on either side 85 metres (279 ft) long and a central arch span of 156 metres (512 ft). It had dual tracks that could be covered with planks to allow vehicular traffic. The steel section was 325 metres (1,066 ft) long, and it had an overall length of 398 metres (1,306 ft). On the eastern bank the railway passed through Erpeler Ley, a steeply rising hill over 150 metres (490 ft) high. The tunnel was 383 metres (1,257 ft) long.[6][7] The arch at its highest measured 28.5 metres (94 ft) above the water. Its main surface was normally about 15 metres (48 ft) above the Rhine.[7]

The 4,640-tonne (5,110-short-ton) structure cost about 2.1 million marks when it was built during World War I. Since the bridge was a major military construction project, both abutments of the bridge were flanked by stone towers with fortified foundations that could shelter up to a full battalion of men.[6] The towers were designed with fighting loopholes for troops.[5] From the flat roof of the towers troops had a good view of the valley.[7] To protect the bridge, both an engineering unit and a military police unit were assigned to the site.

Protection

[edit]The designers built cavities into the concrete piers where demolition charges could be placed.[5] During the Occupation of the Rhineland after World War I, the French filled these cavities with concrete. It was one of the four bridges that were guarded by Americans during the occupation.

In 1938, after the Germans reacquired the Rhineland and control of the bridge, they attached 60 zinc-lined boxes at key structural points to the bridge girders, each capable of containing 3.66 kg (8.1 lb) of explosives. The system was designed to detonate all 60 charges at once. The engineers connected the charges in the piers and the zinc boxes by electrical cable protected by steel pipe to a control panel inside the rail tunnel under Erpeler Ley, where engineers could safely detonate the charges.[5] As a backup, engineers laid primer cord that could be manually ignited. They believed they could destroy the bridge when necessary with minimal preparation.[5]

On 14–15 October 1944, an American bomb had struck a chamber containing the demolition charges of the Mulheim Bridge in Cologne, destroying the bridge. German leader Adolf Hitler reacted by demanding that demolition charges on bridges could only be set when the enemy was within a specific distance, and only exploded by written order. He ordered those "responsible" for the destruction of the Mulheim Bridge court-martialed. This left officers responsible for destroying bridges, in the event that the enemy approached, nervous about both blowing it too soon and the consequences if they failed.[6] In keeping with Hitler's orders, by 7 March 1945, the charges on the Ludendorff Bridge had been removed and were stored nearby.[10]

Capture during World War II

[edit]In March 1945, about 5,100 people lived in Remagen. On the western shore, the Allied bombing campaign had destroyed more than half of Erpel's buildings, including all the buildings between Erpel's marketplace and the bridge, which had been built during the 17th and 18th centuries.[7]

The Rhine near Remagen is about 300 m (980 ft) wide.[5] During Operation Lumberjack, on 7 March 1945, troops of the U.S. Army's 9th Armored Division reached the bridge during the closing weeks of World War II and were surprised to see that the railroad bridge was still standing.[1] It was one of very few bridges remaining across the Rhine, because the Germans had systematically destroyed all of the others in advance of the Allies' attack. Although the bridge was wired with demolition charges, the weak civilian-grade "Donarite" explosives damaged the bridge but failed to bring it down, and Allied engineers risked their lives manually removing the remaining charges before the bridge was captured.[1]

The ability to quickly establish a bridgehead on the eastern side of the Rhine and to get forces into Germany allowed the U.S. forces to envelop the German industrial area of the Ruhr.[1]: 1430–1 Six Allied divisions crossed the damaged bridge, then it was closed for repairs, and a pontoon bridge that had been built across the river was used. The Germans sent several bombing missions to destroy the Remagen bridge; it collapsed due to cumulative damage from the unsuccessful detonation and the bombs on 17 March 1945, 10 days after it was captured.[8] The collapse killed 28 and injured 93[11] U.S. Army Engineers.

The unexpected availability of the first major crossing of the Rhine, Germany's last major natural barrier and line of defence, caused Allied high commander Dwight D. Eisenhower to alter his plans to end the war. Hitler's Nero Decree of 19 March ordered the destruction of any infrastructure that could aid the Allied advance, but the order was not carried out due to opposition from German generals and the rapid Allied advance.[1]: 1432–4 Instead, U.S. forces advanced rapidly through Germany, and by 12 April the Ninth United States Army had crossed the Elbe.[1]: 1434

Post World War II history

[edit]

After the war, the railway crossing was not deemed important enough to justify rebuilding the bridge. Parts of the land used for the approaching railway lines are now used as an industrial estate on the western bank and a park on the eastern bank.

Since 1980, the surviving towers on the western bank of the Rhine have housed a museum called "Peace Museum Bridge at Remagen" containing the bridge's history and 'themes of war and peace'.[12] This museum was partly funded by selling rock from the two piers as paperweights, the two piers having been removed from the river in the summer of 1976 as they were an obstacle to navigation.

In the middle of 2018, the two eastern towers of the bridge were announced to be for sale. Three bids were submitted, but due to the poor condition of the building and expected costs of approximately €1.4 million for its restoration, the sale was expected to be difficult.[13]

Plans were announced to rebuild a pedestrian and cycle bridge on the site of the original railway bridge in 2022.[4]

Gallery

[edit]- The Ludendorff Bridge between 8 and 11 March 1945

- The Ludendorff Bridge on 11 March 1945

- The Ludendorff Bridge in March 1945, showing structural damage

- The Ludendorff Bridge on 17 March 1945 four hours before its collapse

- The Ludendorff Bridge on 17 March 1945 after its collapse

- Collapsed Ludendorff Bridge with sign posted by the US Army: "CROSS THE RHINE WITH DRY FEET COURTESY OF 9TH ARM'D DIV"

- The remains of the Ludendorff Bridge in 1950

- The remains of the Ludendorff Bridge in 2006

- The site of the Ludendorff Bridge, viewed from northwest

In popular culture

[edit]In the film It's a Wonderful Life, during the World War II montage, the narrator, Joseph, says of the character Marty Hatch, "Marty helped capture the Remagen Bridge."[14]

The bridge is featured in the 1996 DOS WWII strategy game Offensive. In the Allied campaign, it needs to be captured intact; in the Axis campaign, it needs to be destroyed to slow the Allied advance.

The final three missions in the 2004 PS2 game Call of Duty: Finest Hour ("Road to Remagen", "Last Bridge Standing" and "Into the Heartland") are based around the battle of Remagen, the second-to-last mission specifically based around the bridge.

The final mission in the 2017 video game Call of Duty: WWII involves the player in helping take the bridge.

The Bridge at Remagen is a 1969 DeLuxe Color war film in Panavision starring George Segal, Ben Gazzara and Robert Vaughn. The film is a highly fictionalized version of actual events during the last months of World War II when the 9th Armored Division approached Remagen and captured the intact Ludendorff Bridge.

The World War II game Hell Let Loose features Ludendorff Bridge in the "Remagen" map where players fight for control of the bridge.[15]

References and notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Shirer, William L. (1950–1983). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. U.S.: Ballatine. p. 1429. ISBN 0449219771.

- ^ "Battle of the Remagen Bridgehead". www.usace.army.mil. March 2020.

- ^ The Bridge. Beyreuth, Germany: 9th Armored Infantry Division.

- ^ a b Connolly, Kate (19 September 2022). "Germany to rebuild bridge over Rhine that collapsed during WW2". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dungan, Tracy. "V-2s on Remagen; Attacks On The Ludendorff Bridge". V2Rocket.com. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d McMullen, Emerson Thomas; Rogers, George (2000). "George Rogers and the Bridge at Remagen". Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "The Ludendorff Bridge Erpel-Remagen". Herrlichkeit Erpel. Archived from the original on 1 June 2004.

- ^ a b "Ludendorff Bridge (Remagen, 1918)". Structurae. n.d. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ MAN Maschinenfabrik Augsburg Nürnberg Bridges Historical advertisement, p. 7

- ^ "De Brug Bij Remagen" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ MacDonald, Charles B., "Chapter XI A Rhine Bridge at Remagen", The Last Offensive, US Army in World War II: European Theater of Operations, p. 230

- ^ "The Bridge at Remagen museum". Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2006.

- ^ Stark, Florian (14 July 2018). "Brücke von Remagen: Wer kauft die Türme der berühmtesten Brücke des Zweiten Weltkriegs?". Die Welt.

- ^ Goodrich, Frances; Hackett, Albert; Capra, Frank; Swerling, Jo. "It's a Wonderful Life (script)". Daily Script. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "Remagen". 24 May 2005.

Further reading

[edit]- "US 9th Engineer Battalion". Archived from the original on 7 May 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2005.

- "The 9th: The Story of the 9th Armored Division". Retrieved 3 June 2006.

- Ludendorff Bridge at Structurae

- "The Ludendorff Bridge". Battlefields Europe. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016.

- "US 8th Air Force ETO Ace Shot Down over Remagen by Allied Gunners". VFW Magazine.

- Hechler Ken (1998). The Bridge at Remagen: The Amazing Story of March 7, 1945, the Day the Rhine River Was Crossed (3rd ed.). Novato, California: Presidio. ISBN 978-0-89141-860-3.

- "The Bridge at Remagen" Archived 10 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Barber Neil

- Lewis Betty (14 July 2001). "Interview with Ken Hechler, WWII Historian author of 'The Bridge at Remagen'". Archived from the original on 11 June 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- "The 9th: The Story of the 9th Armored Division (Originally from Stars and Stripes)". Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- "The Remagen Bridgehead, a US Army Armor School Study 7–17 March 1945 (scanned copy)". Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- Palm Rolf (1985). Die Brücke von Remagen: der Kampf um den letzten Rheinübergang: ein dramatisches Stück deutscher Zeitgeschichte (in German). Scherz. ISBN 978-3-502-16552-1.

- Dittmer, Luther A. (1995). Die Ludendorff Brücke zu Remagen am 7. März 1945: im Lichte bekannter und neuerer Quellen (in German). Institut für Mittelalterliche Musikforschung. ISBN 978-0-931902-35-2.

- https://www.stripes.com/news/what-finished-the-bridge-at-remagen-1.18143

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch