Mark Oliphant

Mark Oliphant | |

|---|---|

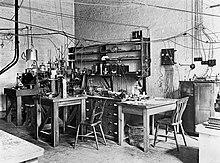

Oliphant in 1939 | |

| Born | Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant 8 October 1901 Adelaide, South Australia, Australia |

| Died | 14 July 2000 (aged 98) Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia |

| Education | |

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | The Neutralization of Positive Ions at Metal Surfaces, and the Emission of Secondary Electrons (1929) |

| Doctoral advisor | Ernest Rutherford |

| Doctoral students | |

| 27th Governor of South Australia | |

| In office 1 December 1971 – 30 November 1976 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Premier | Don Dunstan |

| Lieutenant Governor |

|

| Preceded by | Sir James Harrison |

| Succeeded by | Sir Douglas Nicholls |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Australia Party (until 1977) Australian Democrats (from 1977) |

Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, AC, KBE, FRS, FAA, FTSE (8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian who played an important role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and in the development of nuclear weapons.

Born and raised in Adelaide, South Australia, Oliphant graduated from the University of Adelaide in 1922. He was awarded an 1851 Exhibition Scholarship in 1927 on the strength of the research he had done on mercury, and went to England, where he studied under Sir Ernest Rutherford at the University of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory. There, he used a particle accelerator to fire heavy hydrogen nuclei (deuterons) at various targets. He discovered the respective nuclei of helium-3 (helions) and of tritium (tritons). He also discovered that when they reacted with each other, the particles that were released had far more energy than they started with. Energy had been liberated from inside the nucleus, and he realised that this was a result of nuclear fusion.

Oliphant left the Cavendish Laboratory in 1937 to become the Poynting Professor of Physics at the University of Birmingham. He attempted to build a 60-inch (150 cm) cyclotron at the university, but its completion was postponed by the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe in 1939. He became involved with the development of radar, heading a group at the University of Birmingham that included John Randall and Harry Boot. They created a radical new design, the cavity magnetron, that made microwave radar possible. Oliphant also formed part of the MAUD Committee, which reported in July 1941, that an atomic bomb was not only feasible, but might be produced as early as 1943. Oliphant was instrumental in spreading the word of this finding in the United States, thereby starting what became the Manhattan Project. Later in the war, he worked on it with his friend Ernest Lawrence at the Radiation Laboratory in Berkeley, California, developing electromagnetic isotope separation, which provided the fissile component of the Little Boy atomic bomb used in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in August 1945.

After the war, Oliphant returned to Australia as the first director of the Research School of Physical Sciences and Engineering at the new Australian National University (ANU), where he initiated the design and construction of the world's largest (500 megajoule) homopolar generator. He retired in 1967, but was appointed Governor of South Australia on the advice of Premier Don Dunstan. He became the first South Australian-born governor of South Australia. He assisted in the founding of the Australian Democrats political party, and he was the chairman of the meeting in Melbourne in 1977, at which the party was launched. Late in life he witnessed his wife, Rosa, suffer before her death in 1987, and he became an advocate for voluntary euthanasia. He died in Canberra in 2000.

Early life

[edit]Marcus "Mark" Laurence Elwin Oliphant was born on 8 October 1901 in Kent Town, a suburb of Adelaide. His father was Harold George "Baron" Olifent,[1] a civil servant with the South Australian Engineering and Water Supply Department and part-time lecturer in economics with the Workers' Educational Association.[2][3] His mother was Beatrice Edith Fanny Oliphant, née Tucker, an artist.[4][5] He was named after Marcus Clarke, the Australian author, and Laurence Oliphant, the British traveller and mystic. Most people called him Mark; this became official when he was knighted in 1959.[6]

He had four younger brothers: Roland, Keith, Nigel and Donald; all were registered at birth with the surname Olifent. His grandfather, Harry Smith Olifent (7 November 1848 – 30 January 1916) was a clerk at the Adelaide GPO, and his great-grandfather James Smith Olifent (c. 1818 – 21 January 1890) and his wife Eliza (c. 1821 – 18 October 1881) left their native Kent for South Australia aboard the barque Ruby, arriving in March 1854. He would later be appointed Superintendent of the Adelaide Destitute Asylum, and Eliza Olifent was appointed Matron of the establishment in 1865.[7] Mark's parents were Theosophists, and as such may have refrained from eating meat. Marcus became a lifelong vegetarian while a boy, after witnessing the slaughter of pigs on a farm.[8] He was found to be completely deaf in one ear and he needed glasses for severe astigmatism and short-sightedness.[9]

Oliphant was first educated at primary schools in Goodwood and Mylor, after the family moved there in 1910.[10] He attended Unley High School in Adelaide, and, for his final year in 1918, Adelaide High School.[11] After graduation he failed to obtain a bursary to attend university, so he took a job with S. Schlank & Co., an Adelaide manufacturing jeweller noted for medallions. He then secured a cadetship with the State Library of South Australia, which allowed him to take courses at the University of Adelaide at night.[12]

In 1919, Oliphant began studying at the University of Adelaide. At first he was interested in a career in medicine, but later in the year, Kerr Grant, the physics professor, offered him a cadetship in the Physics Department. It paid 10 shillings a week (equivalent to AUD$89 in 2022), the same amount that Oliphant received for working at the State Library, but it allowed him to take any university course that did not conflict with his work for the department.[13] He received his Bachelor of Science (BSc) degree in 1921 and then did honours in 1922, supervised by Grant.[14] Roy Burdon, who acted as head of the department when Grant went on sabbatical in 1925, worked with Oliphant to produce two papers in 1927 on the properties of mercury, "The Problem of the Surface Tension of Mercury and the Action of Aqueous Solutions on a Mercury Surface"[15] and "Adsorption of Gases on the Surface of Mercury".[16] Oliphant later recalled that Burdon taught him "the extraordinary exhilaration there was in even minor discoveries in the field of physics".[17]

Oliphant married Rosa Louise Wilbraham, who was from Adelaide, on 23 May 1925. The two had known each other since they were teenagers. He made Rosa's wedding ring in the laboratory from a gold nugget from the Coolgardie Goldfields that his father had given him.[18]

Cavendish Laboratory

[edit]In 1925, Oliphant heard a speech given by the New Zealand physicist Sir Ernest Rutherford, and he decided he wanted to work for him – an ambition that he fulfilled by earning a position at the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge in 1927.[18] He applied for an 1851 Exhibition Scholarship on the strength of the research he had done on mercury with Burdon. It came with a living allowance of £250 per annum (equivalent to AUD$45,000 in 2022). When word came through that he had been awarded a fellowship, he wired Rutherford and Trinity College, Cambridge. Both accepted him.[19]

Rutherford's Cavendish Laboratory was carrying out some of the most advanced research into nuclear physics in the world at the time. Oliphant was invited to afternoon tea by Rutherford and Lady Rutherford. He soon met other researchers at the Cavendish Laboratory, including Patrick Blackett, Edward Bullard, James Chadwick, John Cockcroft, Charles Ellis, Peter Kapitza, Egon Bretscher, Philip Moon and Ernest Walton. There were two fellow Australians: Harrie Massey and John Keith Roberts. Oliphant would become especially close friends with Cockcroft. The laboratory had considerable talent but little money to spare, and tended to use a "string and sealing wax" approach to experimental equipment.[21] Oliphant had to buy his own equipment, at one point spending £24 (equivalent to AUD$2,200 in 2022) of his allowance on a vacuum pump.[22]

Oliphant submitted his PhD thesis on The Neutralization of Positive Ions at Metal Surfaces, and the Emission of Secondary Electrons in December 1929.[23] For his viva, he was examined by Rutherford and Ellis. Receiving his degree was the attainment of a major life goal, but it also meant the end of his 1851 Exhibition Scholarship. Oliphant secured an 1851 Senior Studentship, of which there were five awarded each year. It came with a living allowance of £450 per annum (equivalent to A$80,000 in 2022) for two years, with the possibility of a one-year extension in exceptional circumstances, which Oliphant was also awarded.[24]

A son, Geoffrey Bruce Oliphant, was born 6 October 1930,[25] but he died of meningitis on 5 September 1933. He was interred in an unmarked grave in the Ascension Parish Burial Ground in Cambridge, alongside Timothy Cockcroft, the infant son of Sir John and Lady Elizabeth Cockcroft, who had died the year before. Unable to have more children, the Oliphants adopted a four-month-old boy, Michael John, in 1936,[26] and a daughter, Vivian, in 1938.[27]

In 1932 and 1933, the scientists at the Cavendish Laboratory made a series of ground-breaking discoveries. Cockcroft and Walton bombarded lithium with high energy protons and succeeded in transmuting it into energetic nuclei of helium. This was one of the earliest experiments to change the atomic nucleus of one element to another by artificial means. Chadwick then devised an experiment that discovered a new, uncharged particle with roughly the same mass as the proton: the neutron. In 1933, Blackett discovered tracks in his cloud chamber that confirmed the existence of the positron and revealed the opposing spiral traces of positron–electron pair production.[28]

Oliphant followed up the work by constructing a particle accelerator that could fire protons with up to 600,000 electronvolts of energy. He soon confirmed the results of Cockcroft and Walton on the artificial disintegration of the nucleus and positive ions. He produced a series of six papers over the following two years.[29] In 1933, the Cavendish Laboratory received a gift from the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis of a few drops of heavy water. The accelerator was used to fire heavy hydrogen nuclei (deuterons, which Rutherford called diplons) at various targets. Working with Rutherford and others, Oliphant thereby discovered the nuclei of helium-3 (helions) and tritium (tritons).[30][31][32][33]

Oliphant used electromagnetic separation to separate the isotopes of lithium.[34] He was the first to experimentally demonstrate nuclear fusion. He found that when deuterons reacted with nuclei of helium-3, tritium or with other deuterons, the particles that were released had far more energy than they started with. Binding energy had been liberated from inside the nucleus.[35][36] Following Arthur Eddington's 1920 prediction that energy released by fusing small nuclei together could provide the energy source that powers the stars,[37] Oliphant speculated that nuclear fusion reactions might be what powered the sun.[30] With its higher cross section, the deuterium–tritium nuclear fusion reaction became the basis of a hydrogen bomb.[17] Oliphant had not foreseen this development:

... we had no idea whatever that this would one day be applied to make hydrogen bombs. Our curiosity was just curiosity about the structure of the nucleus of the atom, and the discovery of these reactions was purely, as the Americans would put it, coincidental.[17]

In 1934, Cockcroft arranged for Oliphant to become a fellow of St John's College, Cambridge, which paid about £600 a year. When Chadwick left the Cavendish Laboratory for the University of Liverpool in 1935, Oliphant and Ellis both replaced him as Rutherford's assistant director for research. The job came with a salary of £600 (equivalent to AUD$131,000 in 2022).[38] With the money from St John's, this gave him a comfortable income.[23] Oliphant soon fitted out a new accelerator laboratory with a 1.23 MeV generator at a cost of £6,000 (equivalent to AUD$1,310,000 in 2022) while he designed an even larger 2 MeV generator.[39] He was the first to conceive of the proton synchrotron, a new type of cyclic particle accelerator.[40] In 1937, he was elected to the Royal Society. When he died he was its longest-serving fellow.[23]

University of Birmingham

[edit]

Samuel Walter Johnson Smith's imminent mandatory retirement at age 65 prompted a search for a new Poynting Professor of Physics at the University of Birmingham.[41] The university wanted not just a replacement, but a well-known name, and was willing to spend lavishly in order to build up nuclear physics expertise at Birmingham.[42] Neville Moss, its Professor of Mining Engineering and the Dean of its Faculty of Science approached Oliphant, who presented his terms. In addition to his salary of £1,300 (equivalent to AUD$270,000 in 2022), he wanted the university to spend £2,000 (equivalent to A$415,000 in 2022) to upgrade the laboratory, and another £1,000 per annum (equivalent to A$208,000 in 2022) on it. And he did not wish to start until October 1937, to enable him to wrap up his work at the Cavendish Laboratory. Moss agreed to Oliphant's terms.[41]

To obtain funding for the 60-inch (150 cm) cyclotron that he wanted, Oliphant wrote to the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, who was from Birmingham. Chamberlain took up the matter with his friend Lord Nuffield, who provided £60,000 (equivalent to AUD$12,000,000 in 2022) for the project, enough for the cyclotron, a new building to house it, and a trip to Berkeley, California, so Oliphant could confer with Ernest Lawrence, the inventor of the cyclotron. Lawrence supported the project, sending Oliphant the plans of the 60-inch (150 cm) cyclotron that he was constructing at Berkeley, and inviting Oliphant to visit him at the Radiation Laboratory.[43]

Oliphant sailed for New York on 10 December 1938, and met Lawrence in Berkeley. The two men got along very well, dining at Trader Vic's in Oakland. Oliphant was aware of the problems in building cyclotrons encountered by Chadwick at the University of Liverpool and Cockcroft at the Cavendish Laboratory, and intended to avoid these and get his cyclotron built on time and on budget by following Lawrence's specifications as closely as possible. He hoped that it would be running by Christmas 1939, but the outbreak of the Second World War quashed his hopes.[43] The Nuffield Cyclotron would not be completed until after the war.[44]

Radar

[edit]

In 1938, Oliphant became involved with the development of radar, then still a secret. While visiting prototype radar stations, he realised that shorter-wavelength radio waves were needed urgently, especially if there was to be any chance of building a radar set small enough to fit into an aircraft. In August 1939, he took a small group to Ventnor, on the Isle of Wight, to examine the Chain Home system first hand. He obtained a grant from the Admiralty to develop radar systems with wavelengths less than 10 centimetres (4 in); the best available at the time was 150 centimetres (60 in).[45]

Oliphant's group at Birmingham worked on developing two promising devices, the klystron and the magnetron. Working with James Sayers, Oliphant managed to produce an improved version of the klystron capable of generating 400W. Meanwhile, two more members of his Birmingham team, John Randall and Harry Boot, worked on a radical new design, a cavity magnetron. By February 1940, they had an output of 400W with a wavelength of 9.8 centimetres (3.9 in), just the kind of short wavelengths needed for good airborne radars. The magnetron's power was soon increased a hundred-fold, and Birmingham concentrated on magnetron development. The first operational magnetrons were delivered in August 1941. This invention was one of the key scientific breakthroughs during the war and played a major part in defeating the German U-boats, intercepting enemy bombers, and in directing Allied bombers.[46]

In 1940, the Fall of France, and the possibility that Britain might be invaded, prompted Oliphant to send his wife and children to Australia. The Fall of Singapore in February 1942 led him to offer his services to John Madsen, the Professor of Electrical Engineering at the University of Sydney, and the head of the Radiophysics Laboratory at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, which was responsible for developing radar.[46][47] He embarked from Glasgow for Australia on QSMV Dominion Monarch on 20 March. The voyage, part of a 46-ship convoy, was a slow one, with the convoy frequently zigzagging to avoid U-boats, and the ship did not reach Fremantle until 27 May.[48]

The Australians were already preparing to produce radar sets locally. Oliphant persuaded Professor Thomas Laby to release Eric Burhop and Leslie Martin from their work on optical munitions to work on radar, and they succeeded in building a cavity magnetron in their laboratory at the University of Melbourne in May 1942.[49] Oliphant worked with Martin on the process of moving the magnetrons for the laboratory to the production line.[50] Over 2,000 radar sets were produced in Australia during the war.[51]

Manhattan Project

[edit]At the University of Birmingham in March 1940, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls examined the theoretical issues involved in developing, producing and using atomic bombs in a paper that became known as the Frisch–Peierls memorandum. They considered what would happen to a sphere of pure uranium-235, and found that not only could a chain reaction occur, but it might require as little as 1 kilogram (2 lb) of uranium-235 to unleash the energy of hundreds of tons of TNT. The first person they showed their paper to was Oliphant, and he immediately took it to Sir Henry Tizard, the chairman of the Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Warfare (CSSAW).[52] As a result, a special subcommittee of the CSSAW known as the MAUD Committee was created to investigate the matter further. It was chaired by Sir George Thomson, and its original membership included Oliphant, Chadwick, Cockcroft and Moon.[53] In its final report in July 1941, the MAUD Committee concluded that an atomic bomb was not only feasible, but might be produced as early as 1943.[54]

Great Britain was at war and authorities there thought that the development of an atomic bomb was urgent, but there was much less urgency in the United States. Oliphant was one of the people who pushed the American program into motion.[55] On 5 August 1941, Oliphant flew to the United States in a B-24 Liberator bomber, ostensibly to discuss the radar-development program, but was assigned to find out why the United States was ignoring the findings of the MAUD Committee.[56] He later recalled: "the minutes and reports had been sent to Lyman Briggs, who was the Director of the Uranium Committee, and we were puzzled to receive virtually no comment. I called on Briggs in Washington [DC], only to find out that this inarticulate and unimpressive man had put the reports in his safe and had not shown them to members of his committee. I was amazed and distressed."[57]

Oliphant then met with the Uranium Committee at its meeting in New York on 26 August 1941.[56] Samuel K. Allison, a new member of the committee, was an experimental physicist and a protégé of Arthur Compton at the University of Chicago. He recalled that Oliphant "came to a meeting and said 'bomb' in no uncertain terms. He told us we must concentrate every effort on the bomb, and said we had no right to work on power plants or anything but the bomb. The bomb would cost 25 million dollars, he said, and Britain did not have the money or the manpower, so it was up to us." Allison was surprised that Briggs had kept the committee in the dark.[58]

Oliphant then travelled to Berkeley, where he met his friend Lawrence on 23 September, giving him a copy of the Frisch–Peierls memorandum. Lawrence had Robert Oppenheimer check the figures, bringing him into the project for the first time. Oliphant found another ally in Oppenheimer,[56] and he not only managed to convince Lawrence and Oppenheimer that an atomic bomb was feasible, but inspired Lawrence to convert his 37-inch (94 cm) cyclotron into a giant mass spectrometer for electromagnetic isotope separation,[59] a technique Oliphant had pioneered in 1934.[34] Leo Szilard later wrote, "if Congress knew the true history of the atomic energy project, I have no doubt but that it would create a special medal to be given to meddling foreigners for distinguished services, and that Dr Oliphant would be the first to receive one."[55]

On 26 October 1942, Oliphant embarked from Melbourne, taking Rosa and the children back with him. The wartime sea voyage on the French Desirade was again a slow one, and they did not reach Glasgow until 28 February 1943.[60] He had to leave them behind once more in November 1943 after the British Tube Alloys effort was merged with the American Manhattan Project by the Quebec Agreement, and he left for the United States as part of the British Mission. Oliphant was one of the scientists whose services the Americans were most eager to secure. Oppenheimer, who was now the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory attempted to persuade him to join the team there, but Oliphant preferred to head a team assisting his friend Lawrence at the Radiation Laboratory in Berkeley to develop the electromagnetic uranium enrichment—a vital but less overtly military part of the project.[61]

Oliphant secured the services of fellow Australian physicist Harrie Massey, who had been working for the Admiralty on magnetic mines, along with James Stayers and Stanley Duke, who had worked with him on the cavity magnetron. This initial group set out for Berkeley in a B-24 Liberator bomber in November 1943.[62] Oliphant became Lawrence's de facto deputy, and was in charge of the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory when Lawrence was absent.[63] Although based in Berkeley, he often visited Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where the separation plant was, and was an occasional visitor to Los Alamos.[64] He made efforts to involve Australian scientists in the project,[65] and had Sir David Rivett, the head of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, release Eric Burhop to work on the Manhattan Project.[65][66] He briefed Stanley Bruce, the Australian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, on the project, and urged the Australian government to secure Australian uranium deposits.[65][67]

A meeting with Major General Leslie Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project, at Berkeley in September 1944, convinced Oliphant that the Americans intended to monopolise nuclear weapons after the war, restricting British research and production to Canada, and not permitting nuclear weapons technology to be shared with Australia. Characteristically, Oliphant bypassed Chadwick, the head of the British Mission, and sent a report direct to Wallace Akers, the head of the Tube Alloys Directorate in London. Akers summoned Oliphant back to London for consultation. En route, Oliphant met with Chadwick and other members of the British Mission in Washington, where the prospect of resuming an independent British project was discussed. Chadwick was adamant that the cooperation with the Americans should continue, and that Oliphant and his team should remain until the task of building an atomic bomb was finished. Akers sent Chadwick a telegram directing that Oliphant should return to the UK by April 1945.[68]

Oliphant returned to England in March 1945, and resumed his post as a professor of physics at the University of Birmingham. He was on holiday in Wales with his family when he first heard of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[69] He was later to remark that he felt "sort of proud that the bomb had worked, and absolutely appalled at what it had done to human beings". Oliphant became a harsh critic of nuclear weapons and a member of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, saying, "I, right from the beginning, have been terribly worried by the existence of nuclear weapons and very much against their use."[17] His wartime work would have earned him a Medal of Freedom with Gold Palm, but the Australian government vetoed this honour,[23] as government policy at the time was not to confer honours on civilians.[70]

Later years in Australia

[edit]In April 1946, the Prime Minister, Ben Chifley, asked Oliphant if he would be a technical advisor to the Australian delegation to the newly formed United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC), which was debating international control of nuclear weapons. Oliphant agreed, and joined the Minister for External Affairs, H. V. Evatt and the Australian Representative at the United Nations, Paul Hasluck, to hear the Baruch Plan. The attempt at international control was unsuccessful, and no agreement was reached.[71]

Chifley and the Secretary for Post-War Reconstruction, Dr H. C. "Nugget" Coombs, also discussed with Oliphant a plan to create a new research institute that would attract the world's best scholars to Australia and lift the standard of university education nationwide. They hoped to start by attracting three of Australia's most distinguished expatriates: Oliphant, Howard Florey and Keith Hancock.[72] It was academic suicide; Australia was far from the centres where the latest research was being carried out, and communications were much poorer at that time. But Oliphant accepted, and in 1950 returned to Australia as the first Director of the Research School of Physical Sciences and Engineering at the Australian National University.

Within the school he created a Department of Particle Physics, which he headed himself, a Department of Nuclear Physics under Ernest Titterton, a Department of Geophysics under John Jaeger, a Department of Astronomy under Bart Bok, a Department of Theoretical Physics under Kenneth Le Couteur and a Department of Mathematics under Bernhard Neumann.[73]

Oliphant was an advocate of nuclear weapons research. He served on the post-war Technical Committee that advised the British government on nuclear weapons,[74] and publicly declared that Britain needed to develop its own nuclear weapons independent of the United States to "avoid the danger of becoming a lesser power".[75]

The establishment of a world-class nuclear physics research capability in Australia was intimately linked with the government's plans to develop nuclear power and weapons. Locating the new research institute in Canberra would place it close to the Snowy Mountains Scheme, which was planned to be the centrepiece of a new nuclear power industry.[76]

Oliphant hoped that Britain would assist with the Australian program, and the British were interested in cooperation because Australia had uranium ore and weapons testing sites, and there were concerns that Australia was becoming too closely aligned with the United States. Arrangements were made for Australian scientists to be seconded to the British Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell, but the close cooperation he sought was stymied by security concerns arising from Britain's commitments to the United States.[77]

Oliphant envisaged Canberra one day becoming a university town like Oxford or Cambridge.[78] A threat to the future of the university arose in the wake of the 1949 election, when the Liberal Party of Australia led by Robert Menzies won. Many Liberals were opposed to the university, which they saw as an extravagance. Menzies defended it, but in 1954 he announced that it had entered a period of consolidation, with a funding ceiling, ending the possibility of successful competition with universities in Europe and North America. A further blow came in 1959, when the Menzies government amalgamated it with the Canberra University College. Henceforth, it would no longer be a research university, but a regular one, with responsibility for teaching undergraduates. Nonetheless, parts of the university stayed committed to the old mission,[73] and the ANU remained a university where research is central to its activities.[79]

Despite the setbacks, by 2014 the vision of Canberra as a university town would be well on its way to becoming a reality.[80]

In September 1951, Oliphant applied for a visa to travel to the United States for a nuclear physics conference in Chicago. The visa was not refused, nor was Oliphant accused of subversive activities, but neither was it issued. This was the height of the Red Scare. The American McCarran Act restricted travel to the United States, and in Australia the Menzies government was attempting to ban the Communist Party, and was not inclined to support Oliphant against the American government. A subsequent request to travel to Canada via Hawaii in September 1954 was refused by the United States Department of State. Although Oliphant was granted a special waiver that allowed him to transit the US, he preferred to cancel the trip rather than accept this humiliation. The Menzies government subsequently excluded him from participating in or observing the British nuclear tests at Maralinga, nor was he allowed access to classified nuclear information for fear of antagonising the US.[81]

In 1955, Oliphant initiated the design and construction of a 500 megajoule homopolar generator (HPG), the world's largest. This massive machine contained three discs 3.5 metres (11 ft) in diameter and weighing 38 tonnes (37 long tons). He obtained £40,000 (equivalent to A$3,000,000 in 2022) initial funding from the Australian Atomic Energy Commission.[82] Completed in 1963, the HPG was intended to be the power source for a synchrotron, but this was not built.[83] Instead, it was used to power the LT-4 Tokamak and a large-scale railgun that was used as a scientific instrument for experiments with plasma physics. It was decommissioned in 1985.[23]

Oliphant founded the Australian Academy of Science in 1954, teaming up with David Martyn to overcome the obstacles that had frustrated previous attempts. Oliphant was its president until 1956. Deciding that the Academy of Science should have its own special building, Oliphant raised the required money from donations. As chairman of the Building Design Committee, he selected and oversaw the construction of one of Canberra's most striking architectural designs. He also delivered the Academy of Science's 1961 Matthew Flinders Lecture, on the subject of "Faraday in his time and today".[23]

Oliphant retired as Professor of Particle Physics in 1964, and was appointed Professor of Ionised Gases. In this chair he produced his first research papers since the 1930s. He was appointed Professor Emeritus in 1967.[83] He was invited by the premier, Don Dunstan, to become the Governor of South Australia, a position he held from 1971 to 1976. During this period, he caused great concern to Dunstan when he strongly supported the decision of the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, in the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis.[3] He assisted in the founding of the Australian Democrats political party, and he was the chairman of the meeting in Melbourne in 1977 at which the party was launched.[84]

The Age reported in 1981 that "Sir Mark Oliphant warned the Dunstan Government of the 'grave dangers' of appointing an Australian Aborigine, Sir Douglas Nicholls, to succeed him as South Australia's Governor".[85] Oliphant had secretly written, "[t]here is something inherent in the personality of the Aborigine which makes it difficult for him to adapt fully to the ways of the white man." The authors of Oliphant's biography noted that "that was the prevailing attitude of almost the entire white population of Australia until well after World War II".[85]

Oliphant was created a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) in 1959,[86] and was made a Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) in 1977 "for eminent achievement and merit of the highest degree in the field of public service and in service to the crown".[87]

Late in life, Oliphant watched his wife, Rosa, suffer before her death in 1987, and he became an advocate for voluntary euthanasia.[88]

Death

[edit]On 14 July 2000, he died in Canberra, at the age of 98.[89] His body was cremated.[45] His daughter Vivian died from a brain tumour in 2008,[90] after his son Michael died from colon cancer in 1971.[91]

Legacy

[edit]

Places and things named in honour of Oliphant include the Oliphant Building at the Australian National University,[92] the Mark Oliphant Conservation Park,[93] a South Australian high schools science competition,[94] the Oliphant Wing of the Physics Building at the University of Adelaide,[95] a school in the Adelaide suburb of Munno Para West,[96] and a bridge on Parkes Way in Canberra near his old laboratory at the ANU.[97]

His papers are in the Adolph Basser Library at the Australian Academy of Science, and the Barr Smith Library at the University of Adelaide.[98] Oliphant's nephew, Pat Oliphant, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist.[5] His daughter-in-law, Monica Oliphant, is a distinguished Australian physicist specialising in the field of renewable energy, for which she was made an Officer of the Order of Australia in 2015.[99]

Honours and awards

[edit]- 1937 Elected Fellow of the Royal Society[23]

- 1943 Awarded Hughes Medal by the Royal Society[23]

- 1946 Awarded Silvanius Thomson Medal, Institute of Radiology[23]

- 1948 Awarded Faraday Medal by the Institution of Engineers[23]

- 1954 Elected (Foundation) Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science[23]

- 1954 Elected (Foundation) President of the Australian Academy of Science[23]

- 1955 Invited to deliver the Bakerian Lecture by the Royal Society[23]

- 1955 Invited to deliver the Rutherford Memorial Lecture by the Royal Society[23]

- 1956 Awarded Galathea Medal by King Frederik IX of Denmark[23]

- 1959 Created Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire[86]

- 1961 Awarded Matthew Flinders Medal and Lecture[100]

- 1976 Inducted as first Honorary Fellow and a Foundation Fellow of the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering[101]

- 1977 Appointed Companion of the Order of Australia[87]

- Memorials to Mark Oliphant

- Statue on North Terrace, Adelaide

- Text on the statue

- Plaque on the Jubilee 150 Walkway

Bibliography

[edit]- Oliphant, Mark (1949). The Atomic age. London: G. Allen and Unwin. OCLC 880015.

- — (1970). Science and the Future. Bedford Park, South Australia: Flinders University Science Association. OCLC 37096592.

- — (1972). Rutherford: Recollections of the Cambridge Days. Amsterdam: Elsevier Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0-444-40968-3. OCLC 379045.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Family Notices". The Express and Telegraph. South Australia. 2 November 1901. p. 4. Retrieved 5 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "Workers' Educational Association". The Register. 9 October 1928. p. 3. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ a b Bleaney, B. (2001). "Sir Mark (Marcus Laurence Elwin) Oliphant, A.C., K.B.E. 8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000: Elected F.R.S. 1937". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 47: 383–393. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2001.0022.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 3.

- ^ a b "Mick Joffe, interview with Sir Mark Oliphant". Mick Joffe. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 6.

- ^ "Topics of the Day". The South Australian Advertiser. South Australia. 14 April 1865. p. 2. Retrieved 5 April 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 8.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 16.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 19.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 28.

- ^ Burdon, R. S.; Oliphant, M. L. (1927). "The Problem of the Surface Tension of Mercury and the Action of Aqueous Solutions on a Mercury Surface". Transactions of the Faraday Society. 23: 205–213. doi:10.1039/TF9272300205.

- ^ Oliphant, M. L.; Burdon, R. S. (22 October 1927). "Adsorption of Gases on the Surface of Mercury". Nature. 120 (3025): 584–585. Bibcode:1927Natur.120..584O. doi:10.1038/120584b0. S2CID 4069073.

- ^ a b c d Sutherland, Denise (1997). ""Just Curiosity...", Sir Mark Oliphant". University of Melbourne. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ^ a b Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 29.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 30.

- ^ "The History of the Cavendish". University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 37.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Australian Academy of Science – Biographical Memoirs – Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant". Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 43.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 59.

- ^ a b Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 71.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 48–50.

- ^ a b Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 52–55.

- ^ Oliphant, M. L. E.; Rutherford, Lord (3 July 1933). "Experiments on the Transmutation of Elements by Protons". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 141 (843): 259–281. Bibcode:1933RSPSA.141..259O. doi:10.1098/rspa.1933.0117.

- ^ Oliphant, M. L. E.; Kinsey, B. B.; Rutherford, Lord (1 September 1933). "The Transmutation of Lithium by Protons and by Ions of the Heavy Isotope of Hydrogen". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 141 (845): 722–733. Bibcode:1933RSPSA.141..722O. doi:10.1098/rspa.1933.0150.

- ^ Oliphant, M. L. E.; Harteck, P.; Rutherford, Lord (1 May 1934). "Transmutation Effects Observed with Heavy Hydrogen". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 144 (853): 692–703. Bibcode:1934RSPSA.144..692O. doi:10.1098/rspa.1934.0077.

- ^ a b Oliphant, M. L. E.; Shire, E. S.; Crowther, B. M. (15 October 1934). "Separation of the Isotopes of Lithium and Some Nuclear Transformations Observed with them". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 146 (859): 922–929. Bibcode:1934RSPSA.146..922O. doi:10.1098/rspa.1934.0197.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Oliphant, M. L. E.; Kempton, A. R.; Rutherford, Lord (1 April 1935). "The Accurate Determination of the Energy Released in Certain Nuclear Transformations". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 149 (867): 406–416. Bibcode:1935RSPSA.149..406O. doi:10.1098/rspa.1935.0071.

- ^ Eddington, Arthur S. (1920). "The internal constitution of the stars". The Observatory. 43 (1341): 341–358. Bibcode:1920Obs....43..341E. doi:10.1126/science.52.1341.233. PMID 17747682.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 58.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 53.

- ^ Rotblat, Józef (2000). "Mark Oliphant (1901–2000)". Nature. 407 (6803): 468. doi:10.1038/35035202. PMID 11028988. S2CID 36978443.

- ^ a b Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 66–69.

- ^ "A Century of Expertise". University of Birmingham. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014.

- ^ a b Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 74–78.

- ^ Clarke, Dr N. M. "The Nuffield Cyclotron at Birmingham". University of Birmingham. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ a b Bleaney, Brebis. "Oliphant, Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin (1901–2000)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/74397. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 83–90.

- ^ Mellor 1958, pp. 427–428.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Mellor 1958, p. 446.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Mellor 1958, p. 450.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 39–41, 407.

- ^ Gowing 1964, p. 45.

- ^ Gowing 1964, p. 78.

- ^ a b Rhodes 1986, p. 372.

- ^ a b c Holden, Darren (17 January 2018). "The Indiscretion of Mark Oliphant: How an Australian Kick-started the American Atomic Bomb Project". Historical Records of Australian Science. 29: 28–35. doi:10.1071/HR17023.

- ^ Oliphant, Mark (December 1982). "The Beginning: Chadwick and the Neutron". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 38 (10): 14–18. Bibcode:1982BuAtS..38j..14O. doi:10.1080/00963402.1982.11455816. ISSN 0096-3402. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, p. 373.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 44.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Gowing 1964, pp. 256–260.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 183.

- ^ a b c Binnie, Anna (2006). "Oliphant, the Father of Atomic Energy" (PDF). Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales. 139 (419–420): 11–22. doi:10.5962/p.361572. ISSN 0035-9173. S2CID 259734791. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ "Rivett to White". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 5 January 1944. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ "Bruce to Curtin". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 16 August 1943. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ Holden, Darren (15 May 2018). "'On the Oliphant Deign, Now to Sound the Blast': How Mark Oliphant Secretly Warned of America's Post-war Intentions of an Atomic Monopoly". Historical Records of Australian Science. 29 (2): 130. doi:10.1071/HR18008.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 122–124.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 198.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 171–179.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974, p. 45.

- ^ Reynolds 2000, p. 53.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974, p. 147.

- ^ Gowing & Arnold 1974, pp. 336–337.

- ^ Reynolds 2000, pp. 52–53.

- ^ "ANU by 2020" (PDF). Australian National University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ Macdonald, Emma (1 December 2014). "Canberra the most 'university town' in the country, say UC and ANU". Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 188–193.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 229–231.

- ^ a b Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, pp. 247–249.

- ^ "Don's Party Ready to Go". Papua New Guinea Post-courier. 10 May 1977. p. 9. Retrieved 9 May 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "Oliphant did not want Black". The Age. 20 August 1981. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ a b "No. 41590". The London Gazette (1st supplement). 30 December 1958. p. 38.

- ^ a b "Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) entry for Mark Oliphant". Australian Honours Database. Canberra, Australia: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 26 January 1977. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

For eminent achievement and merit of the highest degree in the field of public service and in service to the crown.

- ^ "Handbook of the South Australian Voluntary Euthanasia Society". South Australian Voluntary Euthanasia Society. Archived from the original on 3 May 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ "Sir Mark Oliphant dies". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 18 July 2000. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ "Ms Vivian Wilson". Parliament of Australia. 7 October 2017.

- ^ Cockburn & Ellyard 1981, p. 267.

- ^ "Oliphant Building". Australian National University. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ "Mark Oliphant Conservation Park". Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ "Oliphant Science Awards". South Australian Science Teachers Association. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ "Sir Mark Oliphant (1901–2000)" (PDF). University of Adelaide. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ "Mark Oliphant College B-12". Mark Oliphant College. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Katy Gallagher | Chief Minister, Australian Capital Territory | Parkes Way bridge to honour ANU pioneer" (Press release). ACT Government. 16 June 2010. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Oliphant, Marcus Laurence Elwin". Encyclopaedia of Australian Science. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Edwards, Verity (8 June 2015). "Monica Oliphant: 'tree-hugging' physicist turned to renewables". The Australian. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ "Matthew Flinders Medal and Lecture". science.org.au. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "History". Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

References

[edit]- Cockburn, Stewart; Ellyard, David (1981). Oliphant, the Life and Times of Sir Mark Oliphant. Adelaide: Axiom Books. ISBN 978-0-9594164-0-4.

- Gowing, Margaret (1964). Britain and Atomic Energy, 1939–1945. London: MacMillan. OCLC 670156897.

- Gowing, Margaret; Arnold, Lorna (1974). Independence and Deterrence: Britain and Atomic Energy, 1945–1952, Volume 1, Policy Making. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-15781-7. OCLC 611555258.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946 (PDF). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07186-5. OCLC 637004643. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Mellor, D. P. (1958). The Role of Science and Industry. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 4092792. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- Reynolds, Wayne (2000). Australia's Bid for the Atomic Bomb. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-84914-1. OCLC 46880369.

- Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-44133-3. OCLC 13793436.

Further reading

[edit]- Ramsey, Andrew (2019). The Basis of Everything. Sydney: HarperCollinsPublishers Australia. ISBN 978-1-4607-5523-5. OCLC 1104182720.

- Mason, Brett (2022). Wizards of Oz : how Oliphant and Florey helped win the war and shape the modern world. Sydney, NSW. ISBN 978-1-74223-854-8. OCLC 1345458814.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

[edit]- "Larson Collection interview with Mark Oliphant". IEEE. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2014. Video interview.

- "Oral History Transcript – Sir Mark Oliphant". American Institute of Physics. 3 November 1971. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- "Group photograph of British Mission at Berkeley, 1944". Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch