Margaret Arundell

Margaret Arundell (died 1522) was a wealthy Englishwoman. She is noted for her 1516 will, which details aspects of elite religious practice and also mentions a chain that had belonged to Edward V, one of the Princes in the Tower.[1]

Family and marriage

[edit]

Margaret Arundell was a daughter of John Arundell of Lanherne and his wife Katherine Chideocke or Chiddiock (d. 1479), the widow of William Stafford. The family was Lancastrian in its alliances during the Wars of the Roses, with the exception of her brother Thomas's marriage to an heiress of the Dinham family. Thomas Arundel took part in Buckingham's rebellion against Richard III.[2][3]

Margaret Arundell married Sir William Capel (c.1446-1515), a wealthy draper who was twice Lord Mayor of London.[4] They lived in London and at Rayne, Essex.[5][6] The site of their London house in Bartholomew Lane was known as Capel's Court, and later as Black Swan Yard.[7] Their children included:

- Elizabeth Capell (died 1558), who married William Paulet, 1st Marquess of Winchester.

- Giles Capel (died 1556),[8] who married (1) Isobel Newton, daughter of John Newton and Elizabeth St John, and (2) Mary Roos Denys, widow of the groom of the stool Hugh Denys.[9][10][11]

- Dorothy Capel, who married John Zouche of Harringworth, son of Baron Zouche.[12] He fought for Richard III at Bosworth.[13]

The Capels were able to get their son Giles a place at the court of Henry VII, though their financial activities in the city brought some difficulties.[14] They employed a mason John Wade to build a chantry chapel and tomb for them at St Bartholomew-the-Little.[15] They donated property and lands to the Draper's Company to establish a charity after their deaths. The almsmen beneficiaries would receive two loads of coal yearly.[16] Dame Margaret is known to have made loans, both to family members, and to others, making formal bonds and obligations.[17]

Margaret's own inscribed Latin Bible survives in the Bodleian Library, which she gave to Roger Philpot of Winchester College.[18][19]

The will and historians

[edit]

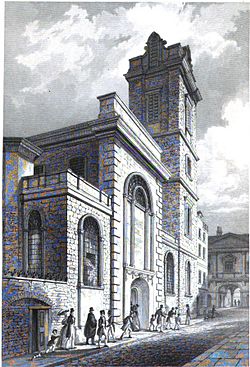

Margaret made her will in 1516. She made a bequest of vestments to the church of St Mawgan at Lanherne in Cornwall where she had been baptised.[20] She was concerned to furnish the Capel family chantry at St Bartholomew-the-Little in London (St Bartholomew-by-the-Exchange, demolished 1840), and had personally embroidered some fabrics, and made crowns (an emblem of the Draper's company) for an altar cloth.[21] She gave a manuscript prayer book and a printed missal for the altar of the chantry, "a great mass book of parchment and written with text hand, it to be amended and corrected, and another mass book printed which they daily now say mass upon". The gifts are comparable with those made by noble women.[22]

The will also mentions domestic furnishings including a bed with valences of crimson satin embroidered with the Capel and Arundell arms, anchor badge, and motto, and red sarcenet silk curtains. The Capel anchor badge was carved in the doorways at Rayne.[23][24] Elizabeth Paulet would receive a book of hours, "a large primer of parchment limned with images and covered with tawny velvet and green damask with three great clasps of silver and gilt",[25] and from her mother's collection of jewellery, "a pomander of gold graven and enamelled with red and white" and a collar of gold of white gilliflowers and red entredeux, and other pieces.[26][27] Dame Margaret left a long gold chain to William Paulet,[28] and six gold chains to her son Giles, noting that she had bought one chain with "long links" from Ridley, a servant of "my Lord of Kent", perhaps George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent or Richard Grey, 3rd Earl of Kent. The Capels acquired land from the Earls of Kent.[29]

Elizabeth Paulet would receive £20 to have in her name and pleasure, and "not her husband to have any account of it".[30] Dame Margaret made special provisions in her lifetime for her two grandchildren by her son Giles Capel, Henry and Edward, by buying land from Giles to secure an income for their benefit, in part to meet a legacy made to them by William Capel. Instead of following the detail of her husband's will, or claiming a third of his goods (known as a dower or terce) she had taken a half of his goods.[31]

Included in the 1516 will, Margaret bequeathed her son Giles Capel a gold chain of her late husband's, which had belonged to Edward V, one of the Princes in the Tower.[32][33] The bequest was intended to entail the chain, the Capel bed with anchor badges, and other items to her grandchildren and the Capel family:

"his faders cheyne which was younge kyng Edwarde the Vth's. To have the forsaid stuffe and cheyne during his life with reasonable werying upon that condicion that after his decease I will that yt remain and be kept by myn executors to the use of Henry Capell and Edward Capell from one to another, And for default of these two children, I will that my daughter Elizabeth Paulet shal'have the forsaid goodes".[34]

This is one of few references to the personal possession of the Princes in Tower after their deaths.[35] Margaret Capel's older half-sister Anne was the wife of James Tyrrell, who is thought to have been involved in the deaths of the Princes in the Tower.[36]

Margaret died in 1522 and was buried at St Bartholomew-the-less. In her will, she had provided for the women to watch over her: "all suche women as shall watche me and be about me at my departing I will they shall be well rewarded after the discrecion of myn executors to pray for my soule".[37]

References

[edit]- ^ Diana Scarisbrick, Jewellery in Britain, 1066-1837: A documentary, social, literary and artistic survey (Norwich: Michael Russell, 1994), p. 28.

- ^ Christine Carpenter, Kingsford's Stonor Letters and Papers 1290–1483 (Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 128.

- ^ H. Fox and O. J. Padel, The Cornish lands of the Arundells of Lanherne (Exeter: Devon and Cornwall Record Society, 2000), pp. ix, xxv, xxix–xxx.

- ^ William Minet, "Capells at Rayne", Transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society, 9:4 (Colchester, 1904), p. 246–247.

- ^ "Noble families. temp. Henry VII", Collectanea Topographica et Genealogica, 1 (London, 1834), p. 306.

- ^ J. G. White, History of the ward of Walbrook in the city of London (London, 1904), pp. 180–184

- ^ Capel's House: Map of Early Modern London

- ^ Calendar Patent Rolls, Henry VII, 2 (London, 1914), p. 414.

- ^ William Minet, "Capells at Rayne", Transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society, 9:4 (Colchester, 1904), p. 246–247.

- ^ Barbara J. Harris, English Aristocratic Women, 1450–1550: Marriage and Family, Property and Careers (Oxford, 2002), p. 216.

- ^ Ethel Dean, Sir Richard Roos: Lancastrian Poet (London, 1961), p. 42 & Appendix B.

- ^ Walter C. Metcalfe, Visitation of Wiltshire (London, 1897), 1565, p. 43

- ^ John Collinson, The History and Antiquities of the County of Somerset, 2 (Bath, 1791), p. 55.

- ^ S. J. Gunn, The Courtiers of Henry VII, The English Historical Review, 108:426 (January 1993), pp. 24, 29–30: Calendar Patent Rolls, Henry VII, 2 (London, 1914), p. 414.

- ^ William Minet, "Capells at Rayne", Transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society, 9:4 (Colchester, 1904), p. 244

- ^ Herbert William, The history of the twelve great livery companies of London (London, 1837), pp. 408–410

- ^ Susan E. James, Women's Voices in Tudor Wills, 1485–1603: Authority, Influence and Material (Ashgate, 2015), p. 219.

- ^ Julia Boffey, "Reading in London in 1501", Mary C. Flannery & Carrie Griffin, Spaces for Reading in Later Medieval England (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), p. 58.

- ^ Suzanne Reynolds, "Songes of the Frere and the Nunne': An unrecorded amorous carol in a Cambridge incunable", Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 16:2 (2017), p. 301.

- ^ Nicholas Orme, Cornish Wills, 1342–1540 (Devon and Cornwall Record Society, 2007), pp. 67, 212: Charles Henderson, The Ecclesiastical History of Western Cornwall, 2 (Truro, 1962), p. 388.

- ^ Barbara J. Harris, English Aristocratic Women and the Fabric of Piety (Amsterdam University Press, 2018), pp. 60, 67, 99

- ^ Barbara J. Harris, English Aristocratic Women and the Fabric of Piety (Amsterdam University Press, 2018), p. 99: Susan E. James, Women's Voices in Tudor Wills (Ashgate, 2015), p. 73, (modernised quotation here).

- ^ Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Essex (London: HMSO, 1916), p. 219

- ^ William Minet, "Capells at Rayne", Transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society, 9:4 (Colchester, 1904), pp. 243, 246: TNA PROB 11/19/456 pp. 10–11.

- ^ Susan E. James, Women's Voices in Tudor Wills (Ashgate, 2015), p. 85, (modernised quotation here).

- ^ Barbara J. Harris, English Aristocratic Women and the Fabric of Piety, 1450–1550 (Amsterdam University Press, 2018), pp. 98–99

- ^ Barbara J. Harris, English Aristocratic Women, 1450–1550: Marriage and Family, Property and Careers (Oxford, 2002), pp. 185–186.

- ^ Barbara J. Harris, English Aristocratic Women, 1450–1550: Marriage and Family, Property and Careers (Oxford, 2002), p. 194.

- ^ Diana Scarisbrick, Jewellery in Britain, 1066-1837: A documentary, social, literary and artistic survey (Michael Russell, 1994), pp. 28, 47, 57: George W. Bernard, "The Fortunes of the Greys, Earls of Kent, in the Early Sixteenth Century", The Historical Journal, 25:3 (September 1982), p. 683.

- ^ Susan E. James, Women's Voices in Tudor Wills, 1485–1603: Authority, Influence and Material (Ashgate, 2015), p. 184.

- ^ Susan E. James, Women's Voices in Tudor Wills, 1485–1603: Authority, Influence and Material (Ashgate, 2015), pp. 156, 204, 214.

- ^ William Minet, "Capells at Rayne", Transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society, 9:4 (Colchester, 1904), p. 243

- ^ Susan E. James, Women's Voices in Tudor Wills, 1485–1603: Authority, Influence and Material (Ashgate, 2015), p. 88: Nicholas Harris Nicolas, Vestusta Testamenta, 2 (London, 1826), p. 595.

- ^ Susan E. James, Women's Voices in Tudor Wills, 1485–1603: Authority, Influence and Material (Ashgate, 2015), p. 88: TNA PROB 11/19/456 p. 10.

- ^ Tim Thornton, "Sir William Capell and A Royal Chain: The Afterlives (and Death) of King Edward V", History: The Journal of the Historical Association, 109:308 (2024), pp. 445–480. doi:10.1111/1468-229X.13430

- ^ Extraordinary new clue about the Princes in the Tower found at The National Archives, The National Archives, 2024, accessed 2 December 2024

- ^ Susan E. James, Women's Voices in Tudor Wills, 1485–1603: Authority, Influence and Material (Ashgate, 2015), p. 19, TNA PROB 11/19, (Margaret Capell).

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch