Medieval harp

The medieval harp refers to various types of harps played throughout Europe during the Middle Ages. The defining features are a three-sided frame (column, harmonic curve, and soundboard)[1] and strings made of wire or gut. The instrument was most popular in Ireland, Scotland, England, Wales, and Scandinavia.[1] Most information about the medieval harp comes from art and poetry of the era, though some original instruments survive and are available to view in museums. Performers play modern reconstructions of medieval harps today. The instrument is the predecessor to the concert grand pedal harp.

Construction and technique

[edit]

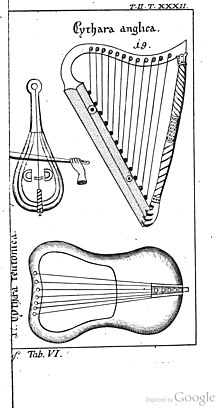

All medieval harps were built with a large vertical box for sound resonance and production.[citation needed] The soundboard was held to the player's body. Strings attached to the soundboard and to tuning pegs within the neck or the harmonic curve of the instrument. The curve became more pronounced in the eleventh century and onwards.[3] The medieval harp usually featured gut strings, though horsehair and silk were used occasionally. In Ireland, the Celtic harp was strung with wire strings.[citation needed] The number of strings varied anywhere from six to thirty. Harps in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries had six to thirteen strings;[4] harps built later in the Middle Ages had more strings. Harps were single strung and tuned diatonically. Octaves most likely contained eight pitches, c, d, e, f, g, a, b, b-flat.[5] A column connected the harmonic curve or neck to the soundboard. Ornate decoration and carving were typical at the joints of these three pieces. Most harps were made from hardwood as opposed to softer spruce as they are today.[citation needed]

Musicians most likely played the instrument with the thumb and second finger, using both hands. Most visual representations depict this technique. And writings confirm that the ring finger was added much later.[citation needed] As with modern day harp technique, the pinky was not used.

History and geography

[edit]- See Origin of the harp in Europe

- See: Rotte for harp lookalike in art

Artistic and literary depictions of the harp are prevalent and "ubiquitous" throughout medieval history.[3] The earliest visual representation of the medieval harp come from Scottish, Pictish, Viking and Norse cultures around the eighth century. These Scandinavian groups may have brought the three-sided harp to the continent of Europe and inspired the development of the medieval harp.[1] Alternatively, the medieval harp may have evolved from the ancient four-sided harp. Artistic representations range from specifically accurate to general approximations which account for the variety in opinions of origin and construction.

The Celtic harp developed into an instrument distinct from other types of medieval harp. For instance, it featured a trapezoid-shaped soundboard, curved column, and wire strings. Irish bards who traveled extensively throughout Europe brought knowledge of this style of instrument to the continent. Dante references this instrument in his writings.[1] In the thirteenth century, he wrote about the construction of Irish harps, noting they were larger than Italian models, and praised the skill of Irish harpers.

Most medieval instruments do not survive today and thus scholars rely on modern reconstructions. A Celtic harp from the fourteenth century is on display at Trinity College in Ireland. An ivory "Romanesque" harp from the fifteenth century survives in the Louvre with twenty-four or twenty-five strings.

Harps in Europe

[edit]According to the New Grove Encyclopedia of Musical Instruments, there are no evidence in images or sculpture to "suggest the existence of harps in western Europe" between the 4th century BCE and the 8th century CE.[6] Ancient examples in "Italo-Greek" vases in the 5th to 4th centuries BCE depict Asian harps.[6] Christian art furnished examples of the existence of the harp in the late 8th to early 10th century CE, in the Dagulf Psalter made in Aachen and the Utrecht Psalter.[6] The Harley Psalter, copied the Utrecht Psalter, but the artist changed the look of the instruments.

- Dagulf Psalter, artwork for cover, late 8th century CE, France.

- Circa 850 A.D., France, Utrecht Psalter. Harp; both hands are visible through the strings.

- Circa 850 A.D., France, Utrecht Psalter.

- Circa 850 A.D., France. Utrecht Psalter. Both lyre and harp visible

- 1000-1050 A.D., England. Harley Psalter, in which the harp is shown with better detail

- Circa 1200 A.D., England. Westminster Psalter. David playing European harp.

Development

[edit]After the medieval harp, the Gothic harp became the popular style of harp in the Renaissance. These harps grew to be larger with more strings. Brays were added for resonance on lower bass strings. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, harp makers in Europe added levers and other mechanisms to increase chromatic capability of the harp. Eventually, in the early nineteenth century Sebastian Erard built the first double action pedal harp, the predecessor to the present day concert grand pedal harp.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Rensch, Roslyn (1950). The Harp. New York: Philosophical Library. p. 18.

- ^ Cook, Ron (2013). The Early Medieval Harp: A Practical Guide. Dlanor Publications. ISBN 978-1-300-83353-6.

- ^ a b Myers, Herbert (2000). Harp. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 330–335. ISBN 0-253-33752-6.

- ^ Cook, Ron (2013). The Early Medieval Harp: A Practical Guide. Dlanor Publications. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-300-83353-6.

- ^ Fulton, Cheryl Anne (2000). Playing the Late Medieval Harp. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 345–354. ISBN 0-253-33752-6.

- ^ a b c Sadie, Stanley, ed. (1984). "Harp: Europe". The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. 2. p. 135.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch