Merced Manor, San Francisco

Merced Manor | |

|---|---|

| Nickname: The White City | |

| Coordinates: 37°44′N 122°29′W / 37.73°N 122.48°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City-county | |

| Government | |

| • Supervisor | Norman Yee |

| • Assemblymember | Catherine Stefani (D)[1] |

| • State senator | Scott Wiener (D)[1] |

| • U. S. rep. | Barbara Lee (D)[2] |

| Population | |

• Total | 3,676 |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP codes | 94132 |

| Area codes | 415/628 |

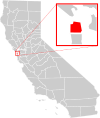

Merced Manor is a neighborhood in southwestern San Francisco, between Stern Grove and Lake Merced. It is bordered by 19th Avenue to the east, Sloat Boulevard to the north, 26th Avenue to the west and Eucalyptus Drive to the south.

Location

[edit]Lowell High School and Lakeshore Alternative Elementary School are located on Eucalyptus Drive, and the Merced Manor reservoir is on Sloat between 22nd and 23rd Avenues. The Stonestown Galleria shopping mall and San Francisco State University are both on 19th Avenue to the south. The Lakeshore Plaza shopping area lies westwards between Everglade Drive and Clearfield Drive.[3] Eastwards down Ocean Avenue are various small stores, including a Walgreens which was once Manor Market.[4] The San Francisco Scottish Rite Masonic Center and West Portal Lutheran Church and School lie diagonal from the northeast corner near the Stern Grove entrance.

History

[edit]Prehistory to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

[edit]Today's San Francisco has been inhabited since about 3000 BC.[5] The area around Merced Manor was once sand dunes (caused by the nearby ocean and wind trajectory) occupied by the Yelamu tribelet of the Ohlone people with a village Ompuromo located just southwest of Lake Merced. An overland Spanish exploration party, led by Don Gaspar de Portolá, arrived on November 2, 1769, the first documented European visit to San Francisco Bay. Seven years later, on March 28, 1776, the Spanish established the Presidio of San Francisco, followed by explorer Juan Bautista de Anza's Mission San Francisco de Asís.[6]

Upon independence from Spain in 1821, the area became part of Mexico's Alta California. Under Mexican rule, the mission system gradually ended, and its lands became privatized. The land of Merced Manor was incorporated into the Rancho Laguna de la Merced, a one-half-square-league territory which, in 1835, was granted to José Antonio Galindo, corporal in El Presidio Real de San Francisco militia in Alta California. Galindo did little to develop the land and sold it in 1837 to Francisco de Haro (1792–1849). Ironically, in 1838, De Haro (as Alcalde) arrested Galindo for the murder of José Doroteo Peralta (1810–1838), son of Pedro Peralta.[7]

With the cession of California to the United States following the Mexican-American War, the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo provided that the land grants would be honored. However, at this time settlers were welcomed and squatted throughout the area. In 1850, the Justice of the Peace for Mission Delores issued a decree allowing certain settlers of San Francisco (generally of the 11th ward south of Lawton Street) to legally parcel the land up among themselves (naming Alfred A Green, E. Goula Buffins, Thomas Green, Alfred Martin, Daniel Green, Robert Green, Charles McGran, Anthony Brown, William Humphreys, Jonah Albert-July, Thomas McCambridge, William Kunez, Clement Humphreys, John H Tillertson, Clement B Ellis, and Joseph Sutter).[8] Contrarily, as required by the Land Act of 1851, a claim for the Rancho by De Haro's family was filed with the Public Land Commission in 1852,[9] though by this time the entirety of today's Merced Manor was primarily owned by the Greene brothers (which led to later legal battles) .

The Greene Family

[edit]Coming from New Brunswick, Canada (sometimes claiming Maine or other states/dates), the Greene family supposedly consisted of 7 brothers. The most prominent early settler was Alfred Augustus Greene (c. 1827–1899), a miner and farmer who's named in the 1850 document (paying $84) and listed as the head of household in the 1852 census.[10] In the census, in addition to his wife and son, two younger brothers are named: Robert Greene and William Henry Greene (c. 1830–1905). An 1863 map of the area by the Pacific Mining Journal[11] illustrates that, at that point, Merced Manor from 24th Avenue westwards was seemingly owned by Alfred (called Rancho Laguna Puerca) and the rest from 24th Avenue eastwards by William. The map also shows scattered properties of brother Daniel L Green and a distant property near the ocean to the west owned by brother George M Green.

According to William's son George, his "father came here in '47, staked off the land, and worked it",[12] converting it from sand dunes into a ranch for potatoes and barley. William's residence in voter registration records is commonly recorded as "Ocean House", flat/apartment #11. Built in 1854 by proprietor Joseph William Leavitt (c.1830-1866),[13] the same year Charles Brown's nearby "Lake House" was leased by P.L. White, the building was a glamorous and notorious housing and vacation destination in the city, attracting different shades of characters. It was located slightly below the border of the two properties on Ocean House Road (today Eucalyptus Drive, split from Ocean Avenue). Burned down in the early 1880s, the site is now occupied by Lowell High School and the Rolph Nicol Jr Playground. In 1859, David C. Broderick and David S. Terry met at the Lake House to choose the location for their famous duel.

In 1856, Alfred was abducted from his bed by the Vigilance Committee after threatening certain wealthy San Franciscans that he could invalidate their land claims with his Delores papers. He was released and found his home ransacked and family traumatized. He left for a short while to Mexico and stayed in Santa Barbara in 1860, switching careers from farming to law, then soon returning to San Francisco. In 1865, he divided the lower half of his ranch to open the Ocean Race Course for horse-racing to complement the success of Ocean House.

In the 1860s, Irish butcher-turned-real-estate-capitalist David Mahoney (c.1820-)[14] bought the Rancho Laguna de La Merced and had another survey made. He sought to extend his property north to more desirable land including that owned by the Greene's. Major litigation followed. There was a conflict at the Ocean House in 1868 which resulted in several arrests.[15] That year, the Spring Valley Water Company bought the water rights for Lake Merced. Mahoney took the Greene's to the US District Court over the land but lost. In 1871, Mahoney appealed to US Supreme Court[16] over the land which ruled in his favor. The family responded by hiring a lawyer. In addition, George (later having a "drooping white mustache") further recounted: "We built a fort, just east of where the Trocadero Inn is now, and we lined it with metal. We stood watch day and night, and Dad hired the best Indian fighter in the West. Then we planted the fence around the land with sticks of dynamite—and let 'em come, we said." When William was away, a Federal Marshall brought 22 men to the property with an order of eviction and his wife Susannah barricaded the house and threatened to pour boiling water on them. The family held in for three months and managed to stay. In 1872, the 1852 claim for Rancho Laguna de la Merced was finally patented to the surviving De Haro children - Josefa de Haro Guerrero Denniston, Rosalia de Haro Andrews Brown, Natividad de Haro Castro Tissot, and Carlotta de Haro Denniston.[17] In 1873,[12] William's oldest son George William Greene (1854–1934) planted exotic Australian eucalyptus around the property which remains today in Stern Grove. The father and son as horticulturalists also wooded the Presidio and Sutro Forest. In 1877, the Spring Valley Water Company started buying the surrounding watershed and at the same time William's wife Susannah M Waterbury died, leaving him with at least 5 children. In 1887, a Special Act of Congress was passed guaranteeing the Greene's their homestead.

In the 1890s, the Spring Valley Water Company began to sell off its landholdings around the lake.[18] In 1892, William brought over a wooden house from Maine or Canada by ship around the horn of South America to the grove which became called the Trocadero Inn, dubbed "the first house built in San Francisco west of Twin Peaks", still standing in Stern Grove as a popular meeting space and wedding area. The first residents at the inn were millionaire lumberman Charles Appleton Hooper, then Adolph Bernard Spreckels (1857–1924), then Hiram Cook who made the place an attractive Sunday breakfast area. George said, “We had a deer park, and a boating pavilion, and a beer garden, and the finest trout farm in California.”[12]

George's siblings eventually left. His father, who made money operating a mine, remarried to a Clara V about 1895 and died sometime before 1910. Meanwhile, the land was seemingly-assumed by the Spring Valley Water Company and the city of San Francisco. Due to the area's low population and distance from downtown, not much is known about damage from the 1906 earthquake other than crack development on the Lake Merced Tunnel arch and the Great Highway.[19] In 1907, politician Abe Ruef (1864–1936) was captured at the Trocadero, hiding there after accusations of corruption. In the 1910s, Sloat Boulevard and 19th Avenue (downwards) were paved with municipal rail lines leading towards St. Francis Circle,[20][21] eventually removed in the 1940s in favor of bus lines. In the 1920s, the area was rented to farmers.[22]

In the 1930s, George vocalized resistance to selling his last parcels of land in fear of urban development and damage to his trees. Around that time, the northwest 19th/Sloat corner lot (now Stern Grove entrance) and southwest 19th/Sloat lot (now annually used to host the Great Pumpkin Patch and Emerald Forest Christmas Trees)[23] were petitioned by the Spring Valley Water Company to be rezoned from residential to commercial as it planned out and sold land to be developed. This was in attempt to construct a gas station which failed to fruition after denial by the city, probably subsequently indefinitely delaying construction on the plot.[24] In 1931, Rosalie Meyer (1869–1956),[25] daughter of Marc Eugene Meyer (1842–1925) and widow of Sigmund Stern (1857–1928), purchased the grove and Trocadero house from George and donated it to the city to become a park, naming it after her late husband. George Greene eventually died in a shack somewhere on the corner (perhaps in the southeast plot) on November 3, 1934[26] as Herzig homes were completed on the east side of 20th Avenue. He was never married. His sister filled out his death information which proves his identity (commonly severely mistaken as the son of William's brother George M Greene who moved to Mexico).[27][28][29][30]

1930s house design and construction

[edit]Development of the neighborhood was marketed as "The White City" due to the color of the houses. Today it consists mostly of two-story residential homes or "manors" constructed from the early 1930s to early 1940s by builders and contractors such as Fernando Nelson (1860–1953),[31][32] George James Elkington (1872–1945),[33] and Arthur Jacob Herzig (1884–1962).[34] Unlike many in the Sunset district, the houses are detached from one another with alleyways in between, making for ease of transportation, deliveries (formerly milkmen), and fire prevention. They also have rear garages accessed from a shared back-road.[35]

Herzig homes were initially constructed on 21st Avenue (around the time he was called to testify as a witness for the trial of Jessie Scott Hughes' murder in 1932).[36] Main entrances tend to be on the second story and the houses were constructed from redwood framing and stucco walls, topped with ceramic shingles and furnished in cooperation with the Hale Brothers and Sterling Furniture Company. Prices started from $6750 (not adjusted for inflation).[37] Later, construction of his houses on 20th Avenue would run off a choice of these designs such as "The Devonshire", Tudor revival with a jutting rectangular bay window, and "The Priscilla", a storybook with an arched inset window and front-door turret.[38] Herzig lived in the large house on the 20th/Sloat corner.[39] Soon after, he constructed another series of houses in Pine Lake Park and then moved to San Mateo following the death of his second wife in 1940.[40][41][42]

Climate

[edit]Temperatures in Merced Manor usually range between 45.7°-85 °F. Precipitation is below average with approximately 22 inches of rain per year though weather can be overcast and humid with nighttime fog. Often September is the hottest month and January is the coldest.[43] The altitude ranges from around 140–240 ft above sea level.[44] The area falls under USDA plant hardiness zone 10b.[45]

Local sites

[edit]Businesses

[edit]- Lakeshore Plaza

- Stonestown Galleria (Built 1952 by the Stoneson Brothers)

- Lakeside businesses on Ocean Avenue[46]

- Great Pumpkin Patch / Emerald Forest Christmas Trees (operating since the late 1990s)

Parks and recreation

[edit]- Lake Merced

- Merced Manor Reservoir (Drinketh Temple built 1912)[47]

- Rolph Nicol Jr. Playground (Named after James Rolph Jr. (1869–1934), 30th Mayor of San Francisco & 27th Governor of California)[48]

- Sigmund Stern Grove (Formerly the Greene family ranch, composed of Australian Eucalyptus, named after philanthropist Sigmund Stern, donated to the city by his wife Rosalie Meyer in 1931, popular festival area)[49][50]

- The Trocadero House (the "first house built in San Francisco west of Twin Peaks")

Schools

[edit]- Lakeshore Alternative Elementary School

- West Portal Lutheran School (Dedicated September 1951)

- Lowell High School (1962 relocation)

- Mercy High School

- San Francisco State University (Campus opened 1953)

Social and religious centers

[edit]- Lakeside Presbyterian Church[51]

- Scottish Rite Masonic Center (Opened 1963)[52]

- St Stephen's Catholic Church (Parish formed August 1950)[53]

- West Portal Lutheran Church (Groundbreaking May 27, 1947)

- Won Buddhism Meditation Temple[54]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ "California's 12th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ "19th Ave Corridor Study" (PDF). 2010-02-12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-11. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- ^ Project, Western Neighborhods. "Manor Market". www.outsidelands.org. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- ^ Stewart, Suzanne B. (November 2003). "Archaeological Research Issues for the Point Reyes National Seashore – Golden Gate National Recreation Area" (PDF). Sonoma State University – Anthropological Studies Center. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ^ Edward F. O'Day (October 1926). "The Founding of San Francisco". San Francisco Water. Spring Valley Water Authority. Archived from the original on July 27, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ Hoover, Mildred B.; Rensch, Hero; Rensch, Ethel; Abeloe, William N. (1966). Historic Spots in California. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4482-9.

- ^ "Mission Book Vol 5". FamilySearch. 1850.

- ^ United States. District Court (California : Northern District) Land Case 380 ND

- ^ Green. "California State Census, 1852". FamilySearch.

- ^ "Harvard Image Delivery Service". iiif.lib.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ a b c "San Francisco History - Trocadero". www.sfgenealogy.org. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ Leavitt. "California, San Francisco Area Funeral Home Records, 1835-1979". FamilySearch.

- ^ Mahoney. "United States Census, 1870". FamilySearch.

- ^ "Land Troubles". San Francisco Chronicle. 1868-09-17. p. 3. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ Mahoney vs Bergin,1871, Reports of cases determined in the Supreme Court of the State of California, Volume 41, pp 423-428, Bancroft-Whitney Company

- ^ Report of the Surveyor General 1844 - 1886 Archived 2013-03-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sara Marcellino; Brandon Jebens (24 May 2001). "The History of Human Use at Lake Merced". San Francisco State University. Archived from the original on 2008-08-29. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ "The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire". content.cdlib.org. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- ^ Project, Western Neighborhods. "19th & Sloat". Outsidelands. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- ^ Project, Western Neighborhods. "Sloat near 19th". Outsidelands. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- ^ Project, Western Neighborhods. "Truck Farm". www.outsidelands.org. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- ^ "Emerald Forest Christmas Trees & Great Pumpkin Patch". Yelp.

- ^ "Attempts to Rezone Sloat Start Clash". The San Francisco Examiner. 13 August 1930.

- ^ Stern. "United States Census, 1920". FamilySearch.

- ^ Greene (1934). "California, San Francisco County Records, 1824-1997". FamilySearch.

- ^ Project, Western Neighborhods. "San Francisco's Lake Merced: Rancho Days". www.outsidelands.org. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ Project, Western Neighborhods. "Ocean Course Racetrack". www.outsidelands.org. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Sigmund Stern Grove: The Jewel of the Sunset | San Francisco History | Guidelines Newsletter". www.sfcityguides.org. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ "Sigmund Stern Grove". www.sfmuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ Nelson. "California Death Index, 1940-1997". FamilySearch.

- ^ Project, Western Neighborhods. "Fernando Nelson". www.outsidelands.org. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- ^ Elkington. "United States Census, 1940". FamilySearch.

- ^ Spring Valley Water Tap Records. San Francisco Public Library.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Interest Centers on New Row". The San Francisco Examiner. 2 February 1935.

- ^ "All Witnesses but One Fail to Help Defense". The San Francisco Examiner. 25 August 1932.

- ^ "Ten High Class Herzig Homes Sold in Month". The San Francisco Examiner. 3 June 1933.

- ^ "Herzig-Sterling Open Early American Home". The San Francisco Examiner. 4 November 1933.

- ^ Herzig, Arthur (April 1940). "United States Census, 1940". FamilySearch.

- ^ "New Frames Rise in Herzig Tract". The San Francisco Examiner. 7 December 1935.

- ^ Herzig, Mary A (19 December 1940). "California Death Index, 1940-1997". FamilySearch.

- ^ "Arthur J. Herzig". The San Francisco Examiner. 6 December 1962.

- ^ "Climate in Zip 94132". BestPlaces.

- ^ "San Francisco". US Topographic Map.

- ^ "San Francisco, California Hardiness Zone Map". PlantMaps.

- ^ Project, Western Neighborhods. "Lakeside District". www.outsidelands.org. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Merced Manor Reservoir: Drinketh Temple, San Francisco, California". RoadsideAmerica.com. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Rolph Nicol Jr Playground". SFRecPark.

- ^ "Stern Grove Festival". www.sterngrove.org. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Sigmund Stern Grove: The Jewel of the Sunset | San Francisco History | Guidelines Newsletter". www.sfcityguides.org. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Lakeside Presbyterian Church". Lakeside Presbyterian Church SF.

- ^ "A Look Inside The San Francisco Scottish Rite Masonic Center". Hoodline. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Our History". www.saintstephensf.org. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "SF Won Buddhist Meditation temple". Yelp.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch