Miami Hurricanes football

| Miami Hurricanes football | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| |||

| First season | 1926; 99 years ago | ||

| Athletic director | Dan Radakovich | ||

| Head coach | Mario Cristobal 3rd season, 22–16 (.579) | ||

| Stadium | Hard Rock Stadium (capacity: 65,326) | ||

| Year built | 1987 | ||

| Field surface | Grass | ||

| Location | Miami Gardens, Florida, U.S. | ||

| NCAA division | Division I FBS | ||

| Conference | Atlantic Coast Conference | ||

| Division | Coastal | ||

| Past conferences | Big East Conference | ||

| All-time record | 665–388–19 (.629) | ||

| Bowl record | 19–23 (.452) | ||

| Claimed national titles | 5 (1983, 1987, 1989, 1991, 2001) | ||

| Unclaimed national titles | 5 (1986, 1988, 1990, 2000, 2002) | ||

| National finalist | 5 (1986, 1988, 1992, 1994, 2002) | ||

| Rivalries | Florida (rivalry) Florida State (rivalry) Louisville (rivalry) Nebraska (rivalry) Notre Dame (rivalry) Virginia Tech (rivalry) Miami University (rivalry) | ||

| Heisman winners | Vinny Testaverde – 1986 Gino Torretta – 1992 | ||

| Consensus All-Americans | 36 | ||

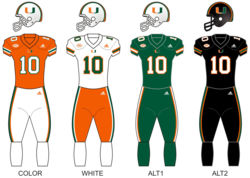

| Current uniform | |||

| |||

| Colors | Orange, green, and white[1] | ||

| Fight song | Miami U How-Dee-Do[2] | ||

| Mascot | Sebastian the Ibis | ||

| Marching band | Band of the Hour | ||

| Outfitter | Adidas | ||

| Website | hurricanesports.com | ||

The Miami Hurricanes football team represents the University of Miami in college football. The Hurricanes compete in the NCAA's Division I Football Bowl Subdivision, the highest level of collegiate football in the nation. The team is a member of the Atlantic Coast Conference, one of the five Power Five conferences in college football. The program began in 1926. Since then, it has since won five AP national championships in 1983, 1987, 1989, 1991, and 2001.[3]

The Miami Hurricanes are among the most storied and decorated football programs in NCAA history. Miami is ranked fourth on the list of all-time Associated Press National Poll Championships, tied with USC and Ohio State and behind Alabama, Notre Dame, and Oklahoma.[4] Two Hurricanes, Vinny Testaverde in 1986 and Gino Toretta in 1992, have won the Heisman Trophy. As of 2023, eight University of Miami players and four coaches have been inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. Among players, Bennie Blades, Don Bosseler, Ted Hendricks, Russell Maryland, Ed Reed, Vinny Testaverde, Gino Torretta, and Arnold Tucker have been inducted. Coaches inducted include Dennis Erickson, Andy Gustafson, Jack Harding, and Jimmy Johnson.[5]

As of the end of the 2023 season, the Miami Hurricanes have a compiled record of 663–388–19 since the program's 1926 founding. In addition to its five national championships, the University of Miami has won nine conference championships and appeared in 42 major bowl games.[6]

The University of Miami also holds a number of NFL draft records, including most first-round selections in a single draft and most consecutive drafts with at least one first-round selection.[7] As of 2024, at least one University of Miami player has been selected in 49 consecutive NFL drafts, dating back to 1975,[8] and 358 Miami Hurricanes have been selected in the NFL Draft overall, the 13th-most among all college football programs.[9]

Among all colleges and universities, as of 2022, the University of Miami holds the all-time record for the most defensive linemen (49) and is tied with USC for the most wide receivers (40) to go on to play in the NFL.[10]

As of 2024, eleven Miami Hurricanes have been inducted into the NFL's Pro Football Hall of Fame: Jim Otto in 1980, Ted Hendricks in 1990, Jim Kelly in 2002, Michael Irvin in 2007, Cortez Kennedy in 2012, Warren Sapp in 2013, Ray Lewis in 2018, Ed Reed in 2019, Edgerrin James in 2020, and Devin Hester and Andre Johnson in 2024.

Since 2008, the University of Miami has played its home games at Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens, roughly 22 miles (35 km) north of the university's primary campus in Coral Gables. Prior to 2008, from 1937 until 2007, Miami played their home games at the Miami Orange Bowl in the Little Havana section of Miami, which was demolished in 2008 after 71 years of use by the NFL's Miami Dolphins, the Hurricanes, and for other athletic and entertainment purposes.

In December 2021, the University of Miami announced the appointment of Mario Cristobal as the team's new coach. Cristobal signed a 10-year, $80 million contract with the Hurricanes.[11]

History

[edit]Early history (1926–1978)

[edit]

1920s

[edit]The University of Miami football program began with a freshman team in 1926.[12] The program's first game was a 7–0 victory over Rollins College on October 23, 1926 before 304 fans.[13] Under the guidance of head coach Howard "Cub" Buck, a former NFL player, the freshman team posted an undefeated 8–0 record in its inaugural season.[14] Two of Miami's wins in 1926 came against the University of Havana,[15] one on Thanksgiving Day in Miami and one in Havana, Cuba, on Christmas Day. The Hurricanes won both games against the University of Havana by an identical shutout score of 23–0. The Hurricanes won their last home game of its inaugural 1926 season against Howard College, now Samford University, 9–7, at the University of Miami's University Stadium. Its win over Howard College was also the first Hurricane football game played on New Year's Day.[16]

The following year, in 1927, the team adopted the "Miami Hurricanes" as the name for its athletic teams. The origins of the name are not exactly clear; some reports suggest the name was a reference to the devastating power of the 1926 hurricane that postponed the program's first game by a month, and others that it was suggested by a player in response to rumors that university officials wanted to name the team after local flora or fauna.[17][18]

Varsity competition began in 1927, with the Hurricanes beating Rollins, 39–3, in its first game and going on to a 3–6–1 record.[19] The team improved to 4–4–1 in 1928,[20] but the program fired Buck, who was replaced prior to the 1929 season with J. Burton Rix, previously head coach at Southern Methodist.[15] Rix's arrival was funded by a group of local businessmen.[21]

1930s

[edit]Rix was replaced the following season, in 1930, by Ernest Brett. The Hurricanes played Temple in its first game outside the South, losing 34–0 in a game played in Atlantic City, New Jersey.[15] On October 31, 1930, the Hurricanes played in one of the nation's first night games, facing Bowden College in Miami.[22]

Brett only lasted one year, and Tom McCann became the program's fourth head coach in 1931.[23] Under McCann, the football program experienced its most successful seasons to that date.

Following a difficult first year, the Hurricanes recorded a winning record in the 1932 season and served as host to the inaugural Palm Festival, later renamed the Orange Bowl, where it defeated Manhattan College 7–0 at Moore Park in Miami.[15] A 5–1–2 campaign and another Palm Festival berth followed in 1933, and in 1934, the program played in its first official bowl game, losing to Bucknell in the first Orange Bowl, 26–0.[15] In 1935, a group of Hurricanes' football supporters sought to hire Red Grange as coach,[24] but the move was vetoed by President Bowman Foster Ashe in part because of what was perceived as the excessive $7,500 salary that Grange sought.[25] Irl Tubbs took over as head coach in 1935. The Hurricanes compiled an 11–5–2 record in his two seasons,[26] but the team failed to reach a bowl game in either year.[27]

After Irl Tubbs resigned following the 1936 season to become head coach at Iowa,[28] Jack Harding was hired to serve as both head football coach and athletic director at the University of Miami.[13] In 1937, the Hurricanes moved into the brand new Burdine Municipal Stadium, renamed the Orange Bowl in 1959, located in Little Havana just west of Downtown Miami.[13] The following year, Miami played archrival Florida for the first time, defeating the Gators 19–7 at Florida Field, and won the program's first Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association title with an 8–2 record.[29]

1940s

[edit]

Harding led the Hurricanes to an eight-win season in 1941 and a seven-win campaign in 1942 prior to being called away for service in World War II.[13] Eddie Dunn, a former star running back for the Hurricanes under Harding, stepped into the void and served as head coach during Harding's two-year absence during World War II.[30] In 1943, the Hurricanes won five games,[31] but they faltered the following year, in 1944, winning just once and losing seven and tying one game.[32]

Harding returned in 1945, and the Hurricanes improved to 9–1–1, and returned to the Orange Bowl for the first time since 1934, where they defeated Holy Cross 13–6.[33]

1950s

[edit]Harding was succeeded by Andy Gustafson, who introduced a "drive series" offense, which featured an option-oriented attack from the Split-T formation that relied on zone blocking and either a fullback fake or carry on every play.[34][35] Under Gustafson, the Hurricanes went 9–1–1 in 1951, including a 35–13 win in its first-ever game against rival Florida State. The same season, the Hurricanes produced their first All-American, Al Carapella, and returned to the Orange Bowl, losing to Clemson 15–14.[13][36] The following season, the Hurricanes won eight games and went to a bowl game in consecutive years for the first time in school history, shutting out Clemson 14–0 in a rematch at the Gator Bowl.

1960s

[edit]In the later years of Gustafson's tenure, two-time All-America quarterback George Mira guided the Hurricanes to berths in the 1961 Liberty Bowl and the 1962 Gotham Bowl, where they lost both games.[37][38]

In 1963, the team struggled to a 3–7 record.[39] Nevertheless, Mira, who set many of the school's passing records during his four years at Miami, appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated and finished fifth in the Heisman Trophy voting as a senior.[13][40][41]

Following the season, Gustafson decided to step down as head coach and Charlie Tate, an assistant at Georgia Tech, was hired to replace him.[42] Gustafson has the Hurricane record for most years as head coach (16) and most wins (93).[43][44][45] Charlie Tate's first seasons at Miami were uneventful, with the team posting a 4–5–1 record in 1964[46] and a reverse 5–4–1 record in 1965.[47] 1966 brought the arrival of defensive end Ted Hendricks, the only three-time All-American in school history,[48] and the Hurricanes won eight games, earning a trip to the Liberty Bowl, where they defeated No. 9 Virginia Tech, 14–7.[13]

In December 1966, the program was integrated when African-American wide receiver Ray Bellamy signed a letter of intent to play football at the university.[49] The Hurricanes returned to bowl play in 1967, appearing in the Bluebonnet Bowl, where they lost to Colorado 31–21.[50] The Hurricanes had a 5–5–0 season in 1968[51] and 4–6–0 in 1969.[52]

1970s

[edit]Tate resigned as head coach two games into the 1970 season, later citing burn out and fatigue from "fighting the money battle and other battles" as the basis for his decision.[53] Walt Kichefski, an assistant on Tate's staff, was elevated to head coach in the wake of Tate's resignation and coached the team to a 3–8 record in 1970.[54] He was not retained the following season.

On December 20, 1970, Fran Curci, a former All-American quarterback for the Hurricanes under Andy Gustafson, was named as the program's new head coach.[55] Curci's 1971 team improved by a game, but rival Florida Gators defeated the Hurricanes in a game that came to be known as "the Gator Flop".[56] The Gators led throughout the game and were up 45–8 when John Reaves threw an interception to the Hurricanes' defense with little time left in the fourth quarter. Reaves needed just 15 more passing yards to break the NCAA record for career passing yards.[57]

Lou Saban, formerly head coach of the NFL's Buffalo Bills, Denver Broncos, and Boston Patriots,[49] was hired on December 27, 1976, as the team's new head coach.[13] The Hurricanes won only three games in 1977, but Saban was able to put together a well-regarded recruiting class that included future Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback Jim Kelly of East Brady, Pennsylvania.[49] Kelly had been recruited by Penn State as a linebacker and agreed to come to Miami after Saban promised him he would play quarterback.[49] Among the other 30 signees in Saban's first recruiting class were 11 future NFL players.[13] The Hurricanes improved by three games in Saban's second season and Ottis Anderson emerged as an NFL talent. Anderson became the first University of Miami running back to rush for 1,000 yards in a season and led the team in rushing for three straight seasons from 1977 through 1979. Anderson set numerous school rushing records and was the Hurricanes' career rushing leader until 2014, when he was overtaken by Duke Johnson.[13] After just two seasons, Saban left after the 1978 season to take the head coaching position at Army.[49][58]

Howard Schnellenberger era (1979–1983)

[edit]

In the wake of Saban's departure, the extensive coaching upheaval the Hurricanes faced in the prior decade, and various fiscal challenges then confronting the university, the university's board of trustees considered holding a vote on whether to reclassify the football program at the Division I-AA level, or even eliminate it altogether.[59] University of Miami executive vice president John Green successfully convinced the board to give Division I-A football another shot. To replace Saban, the Hurricanes hired Howard Schnellenberger, the former head coach of the Baltimore Colts from 1972 to 1974 and the offensive coordinator for the Miami Dolphins under Don Shula. In 1972, Shula and Schnellenberger led the Dolphins to the first and only undefeated, Super Bowl-winning season in NFL history.[60][61][59] In addition to his NFL experience, Schnellenberger had played end at Kentucky from 1952 to 1956 under head coach Bear Bryant and then served as Bryant's offensive coordinator at Alabama from 1961 to 1965, helping the Crimson Tide win three national championships in 1961, 1964, and 1965.[62]

At the outset of his tenure, Howard Schnellenberger announced to his staff and players his intention to win a national championship within five years, a bold claim for a program that was seemingly on its last legs.[63] His five-year plan had two main priorities: installing a pro-style passing offense and upgrading the talent level on the roster through a new recruiting strategy aimed at heavily targeting the best local talent from the city of Miami and the region of South Florida, a strategy that would drastically change national recruiting in the state of Florida in the coming years.[64] On the recruiting front, Schnellenberger spoke of mining the "State of Miami", which entailed fencing off the fertile South Florida recruiting base from other programs and cherry-picking the rest of the nation for a few choice recruits.[65] To help with the new pro-style offense, Schnellenberger hired former Baltimore Colts quarterback Earl Morrall as a volunteer quarterbacks coach.[64] Schnellenberger also sought to exploit the freedom provided by Miami's independent schedule to gain "intersectional exposure" and make the program "national".[64]

On the field, Miami went 5–6 in Schnellenberger's debut season,[66] which was highlighted by a 26–10 upset win at No. 16 Penn State in which redshirt freshman Jim Kelly threw for 280 yards and three touchdowns in his first career start as Miami's quarterback.[67]

Schnellenberger set a bowl berth as the goal of the 1980 campaign and the team made good on its head coach's expectations, winning nine games and earning a trip to the 1981 Peach Bowl, where the Hurricanes defeated Virginia Tech 20–10.[49] The bowl berth was Miami's first since 1967 and the team finished the season ranked 18th in both the AP and Coaches' Polls.

Miami continued to improve in 1981, going 9–2[68] and defeating No. 1 Penn State 17–14 in a late-October game at the Orange Bowl.[69] In the season's final game, the Hurricanes topped rival Notre Dame for the first time since 1960, 37–15, finishing the season eighth in the AP Poll.[70]

The following season, the team finished with four losses following Kelly's shoulder injury.[71] Entering the 1983 season—the fifth of Schnellenberger's tenure—the program had to find a replacement for the recently graduated Kelly. Ultimately, Schnellenberger chose Bernie Kosar as the team's starting quarterback over fellow redshirt freshman Vinny Testaverde.[72]

1983 season and first national championship

[edit]The 1983 Miami Hurricanes started the season unranked and lost 28–3 at Florida in their first game, though Kosar tied George Mira's single-game school record of 25 pass completions.[49] The Hurricanes rallied by winning their next 10 games, including a 20–0 early-season shutout of Notre Dame,[73] and earned a berth to the 1984 Orange Bowl to play the undefeated, top-ranked Nebraska team that had both Mike Rozier and Turner Gill.

The Orange Bowl-berth was Miami's first since 1951, but the program's first national championship remained a long shot, as the Hurricanes entered the game ranked fifth. Miami got much needed help early on New Year's Day when second-ranked Texas, the nation's other undefeated team, lost in the Cotton Bowl Classic and fourth-ranked Illinois lost in the Rose Bowl.[74] Behind Kosar's passing, Miami jumped out to a 17–0 lead, but Nebraska battled back and cut Miami's lead to 31–24 in the fourth quarter.[74] With 48 seconds remaining, Nebraska scored a touchdown to make it 31–30 and, being the number one-ranked team in the nation, needed only to kick the extra point to tie the game and put itself in position to win the national championship. Nebraska head coach Tom Osborne elected to go for the win and attempt a two-point conversion instead.[74] On the ensuing play, Miami safety Kenny Calhoun tipped away Gill's pass to receiver Jeff Smith in the end zone, saving the game and winning Miami the national championship when it leap-frogged No. 3 Auburn to finish first in the final polls.[74] Although Schnellenberger had made good on his five-year plan to win a national championship, he left after the season to accept a head coaching position in the USFL.[75]

Jimmy Johnson era (1984–1988)

[edit]

Two weeks later, athletic director Sam Jankovich hired Oklahoma State head coach Jimmy Johnson to fill the vacancy.[75] One of Jimmy Johnson's immediate priorities upon taking over as Miami head coach was to switch to a 4–3 defense.[76] Johnson wanted to implement the change for his first season, but lacking the time, personnel, and staff, he decided to postpone the switch and kept Schnellenberger's 5–2 defensive package for the 1984 season.[76]

The team struggled to an 8–5 record in Johnson's first season, losing a number of noteworthy games.[77] In the next-to-last game of the regular season, the No. 6 Hurricanes squandered a 31–0 halftime lead against Maryland and lost 42–40 in what was then the biggest comeback in NCAA football history.[78] The following week, Miami lost 47–45 when Boston College's Doug Flutie connected with Gerard Phelan for a 48-yard Hail Mary touchdown on the final play in what has been called the Hail Flutie game.[79] The Hurricanes ended the season on a three-game losing streak by dropping the 1985 Fiesta Bowl to UCLA, 39–37, in a game that featured six lead changes.[80]

During the off-season, Johnson made a number of coaching changes, facilitating the switch to the 4–3 defense, and junior Vinny Testaverde succeeded early-graduate Bernie Kosar at quarterback.[49]

The 1985 team opened the season with a loss at Florida[81] before winning their next four games, including a 38–0 win over Cincinnati that began a then NCAA-record 58 game home winning streak,[82] heading into a matchup at No. 3 Oklahoma. Facing the nation's top-rated defense, Testaverde amassed 270 yards passing and threw touchdowns to Michael Irvin and Brian Blades, while also running for an additional score, in a 27–14 win over the Sooners.[49][83] The Hurricanes ascended to number two in the rankings following a 58–7 victory over Notre Dame in the final game of the regular season,[84] earning a trip to the Sugar Bowl to play the No. 8 Tennessee Volunteers. With No. 1 Penn State losing to Oklahoma in the Orange Bowl, Miami was in position to capture its second national championship, but those hopes were dashed with a lopsided 35–7 loss to Tennessee.[85]

Miami opened its 1986 season as the third-ranked team in the country and climbed to number two after winning its first three games, setting up a No. 1 vs. No. 2 showdown at the Orange Bowl against top-ranked and defending national champion Oklahoma.[49][83] After much pre-game trash-talk between Oklahoma's Brian Bosworth and Miami's Melvin Bratton and Alonzo Highsmith, Testaverde tossed four touchdown passes in a 28–16 win.[49][83] Testaverde's performance led Oklahoma head coach Barry Switzer to remark that he had "never seen a better quarterback" in his 21 years with the Sooners, and at the conclusion of the regular season, Testaverde was awarded the Heisman Trophy with the fifth largest margin of victory in the voting's history.[86]

Having seized the number one ranking with the win over Oklahoma, the Hurricanes finished the regular season at 11–0, outscoring their opponents 420–136, and accepted a bid to the 1987 Fiesta Bowl to play No. 2 Penn State.[87][88] There, the team's "outlaw" image grew when players like Dan Sileo was doing interviews in a Hells Angel jacket, plus arriving in Arizona clad in fatigues and Jerome Brown staged a walkout of a pre-game steak fry attended by both teams.[87] Before an estimated television audience of 70 million people, Penn State upset the heavily favored Hurricanes 14–10 to win the national championship, forcing seven turnovers, including Pete Giftopoulus' game-sealing interception of Testaverde in the end zone in the game's final seconds.[49][87][88][89]

1987 season and second national championship

[edit]Led by Michael Irvin and new quarterback Steve Walsh, the 1987 Miami Hurricanes won the school's second national championship and completed its first undefeated varsity season.[13] The season was highlighted by one of the most memorable games in the history of the Florida State–Miami football rivalry. Trailing No. 4 Florida State 19–3 in the third quarter at Doak Campbell Stadium, the Hurricanes rallied to take a 26–19 lead late in the fourth quarter on a 73-yard touchdown pass from Walsh to Irvin. Florida State responded with a touchdown in the final minute, but Seminoles head coach Bobby Bowden opted to go for two points and the win rather than kick the extra-point for a tie, and Miami's Bubba McDowell broke up the conversion pass in the end zone to preserve the 26–25 victory.[90]

Following the 1987 season, more than 60 players on the combined rosters for the game went on to play in the NFL.[91] The 12–0 campaign was capped by a 20–14 win over the then-No. 1 Oklahoma Sooners in an Orange Bowl billed as "The Game of the Century".[83] The win was Miami's third over Oklahoma in the last three seasons, accounting for Oklahoma's only losses during that time period.[83]

1988 season

[edit]

The Hurricanes had a then-school record 12 players from the 1987 team selected in the following spring's NFL draft,[49] including Irvin and Bennie Blades, but with Walsh returning in 1988, the team gained the number one ranking with a season-opening 31–0 shutout of then-No. 1 Florida State at the Orange Bowl.[13] The following week, Miami scored 17 points in the final 5 minutes and 23 seconds to top No. 4 Michigan 31–30 at Michigan Stadium.[92] Hopes of a repeat national championship were dashed, however, in the so-called Catholics vs. Convicts game, with Miami dropping an emotional 31–30 loss to eventual-national champion Notre Dame on a failed two-point conversion pass in the final minute.[49][93][94]

Johnson left the program in February 1989 to become the head coach of the NFL's Dallas Cowboys,[95] ending his tenure at Miami with a 52–9 overall record and a 44–4 mark over his last four seasons.[96][49]

Dennis Erickson era (1989–1994)

[edit]Despite having the support of students, players, and even the Miami police and fire departments, offensive coordinator Gary Stevens was bypassed for the head coaching job and athletic director Sam Jankovich chose Dennis Erickson of Washington State to succeed Jimmy Johnson instead.[97]

1989 season and third national championship

[edit]In 1989, Erickson became just the second Division I head coach to win a national championship in his first season at a school.[13][98] Erickson's 1989 team, led by Craig Erickson (no relation) at quarterback,[99] rebounded from a 24–10 mid-season loss at Florida State[100] and moved back into the national championship picture with a 27–10 win over then-top-ranked Notre Dame in the final regular-season game.[101] Miami's 33–25 win over No. 7 Alabama in the Sugar Bowl, combined with No. 1 Colorado's loss to Notre Dame in the Orange Bowl, earned the program its third national championship.[98][102]

On October 28, 1989, Miami mascot Sebastian the Ibis was tackled by a group of police officers for attempting to put out Chief Osceola's flaming spear prior to Miami's game against long-standing rival Florida State at Doak Campbell Stadium in Tallahassee. Sebastian was wearing a fireman's helmet and yellow raincoat and holding a fire extinguisher. When a police officer attempted to grab the fire extinguisher, the officer was sprayed in the chest. Sebastian was handcuffed by four officers but ultimately released. Miami quarterback Gino Torretta, who started the game in place of injured Craig Erickson, told ESPN, "Even if we weren't bad boys, it added to the mystique that, 'Man, look, even their mascot's getting arrested.'"[103]

Miami entered the following season as the number one team in the country, but a 28–21 upset loss to Ty Detmer and No. 16 BYU in the opener derailed both the team's national championship chances and Craig Erickson's nascent Heisman campaign.[104] Later in the year, the Hurricanes lost to Notre Dame 29–20 in a game dubbed the "Final Conflict", as Notre Dame had decided to discontinue the 27-game rivalry,[105] feeling the intensity of the series had reached an unhealthy level.[49] Miami ended the season with a 46–3 Cotton Bowl Classic victory over No. 3 Texas in the 1991 Cotton Bowl Classic in which the team was penalized a bowl- and school-record 16 times for 202 yards, including nine unsportsmanlike conduct or personal foul penalties.[106] On one play, Randal Hill scored on a 48-yard touchdown reception and continued to sprint out of the end zone and up the Cotton Bowl tunnel, where he then pretended to shoot at the Longhorns with imaginary pistols.[49] The program was widely criticized for its conduct, with Will McDonough of the Boston Globe likening the Cotton Bowl Classic display to a "wilding" and Bill Walsh calling it "the most disgusting thing [he'd] ever seen in college sports".[49] After the season, the NCAA responded with the so-called "Miami Rule", which made it a 15-yard penalty to engage in excessive celebration or flagrant taunting.[49][107] Also during the off-season, Miami ended its 48-year status as an independent and joined the Big East Conference.[108]

1991 season and fourth national championship

[edit]The 1991 Hurricanes finished 12–0 and captured the program's fourth national championship in nine years behind quarterback Gino Torretta and a linebacking corps that featured Jessie Armstead and Micheal Barrow.[109] Miami's toughest test came in mid-November at then-No. 1 Florida State in the initial Wide Right game; with the No. 2 Hurricanes leading 17–16 in the final minute of the game, Florida State kicker Gerry Thomas' potential game-winning field goal attempt sailed "wide right" of the uprights.[110] Miami completed the second undefeated season in school history with a 22–0 shutout of No. 11 Nebraska in the 1992 Orange Bowl[111] and finished first in the AP Poll, splitting the national championship with Coaches' Poll champ Washington.[13]

1992 through 1994 seasons

[edit]Hurricane Andrew devastated much of South Florida in August 1992,[112] causing the program to relocate its preseason practice sessions north to Dodgertown in Vero Beach.[13] That season, Miami went 11–0 against the second-toughest schedule in the country,[113] topping No. 3 Florida State in Wide Right II and No. 7 Penn State the following week in Beaver Stadium.[13] Meanwhile, Torretta became the second Hurricane to win the Heisman Trophy, throwing for 19 touchdowns and 3,060 yards on the season and setting 11 school passing records during his career.[13][114] Miami earned a trip to the 1993 Sugar Bowl, where the top-ranked and heavily favored Hurricanes were denied a repeat national championship by No. 2 Alabama, 34–13.[115][116] The Sugar Bowl loss ended the program's 29-game winning streak, which dated to 1990.[116] The Hurricanes were frequently thrown off their rhythm by Alabama's 11-man fronts. Torretta threw three interceptions, one fewer than he had all season, in what would be the only loss of his collegiate career.[117] After the 1992 season, defensive coordinator Sonny Lubick left to take the head coaching position at Colorado State.[118]

Although it was not apparent at the time, the Sugar Bowl loss marked the start of a downturn in Miami's fortunes. In 1993, the Hurricanes lost three games in a season for the first time since 1984,[119] failed to win the Big East for the first time since joining in 1991, and was shut out in the Fiesta Bowl by Arizona, still the worst loss Miami has ever suffered in a bowl game.[13] This led observers to wonder whether the Hurricanes were in decline.[49][120]

In 1994, Miami defeated Georgia Southern in the season opener for its 58th consecutive home win, setting an NCAA record.[121] The streak, which began in 1985, was snapped two weeks later when Washington defeated the Hurricanes 38–20 at the Orange Bowl.[122] Led by All-American defensive tackle Warren Sapp[123] and sophomore linebacker Ray Lewis,[124] the team rebounded to earn a berth in the 1995 Orange Bowl, where No. 1 Nebraska outscored Miami 15–0 in the final quarter to win the game, 24–17, and the national championship.[13][125]

With the threat of NCAA sanctions hovering over the program for a variety of infractions, Erickson stepped down after the 1994 season to become head coach of the NFL's Seattle Seahawks.[126][49] Erickson departed Miami with a 63–9 record over six seasons and the highest winning percentage (.875) and most national championships (2) of any coach in school history.[127][125]

Butch Davis era (1995–2000)

[edit]

Following Erickson's departure, Miami initially pursued former University of Miami defensive coordinator and then-Colorado State head coach Sonny Lubick; however, he withdrew from consideration and opted to remain with the Rams.[128] Eventually, Miami settled on another former Hurricanes defensive assistant coach, then-Dallas Cowboys defensive coordinator Butch Davis.[129]

The Hurricanes finished Davis's first season with a record of 8–3.[130] However, on December 20, 1995, the NCAA announced that Miami would be subject to severe sanctions for numerous infractions within the athletic department.[131] The Hurricanes were forced to sit out postseason play for the first time since 1982 and docked 31 scholarships from 1996 to 1998.[131] Miami had actually self-reported the violations in 1991. However, when the Department of Education got word that school officials helped athletes fraudulently obtain Pell Grants, it asked Miami to stop its own investigation while it conducted its own. Ultimately, 60 athletes were implicated, but all of them avoided criminal charges after being sent through a pretrial diversion program.[132]

In 1994, Tony Russell, a former University of Miami academic advisor, pleaded guilty to helping more than 80 student athletes, 57 of whom were football players, falsify Pell Grant applications in exchange for kickbacks from the players themselves. The scandal dated all the way back to 1989 and fraudulently secured more than $220,000 in federal grants. Federal officials later said that Russell had engineered "perhaps the largest centralized fraud ever committed" in the history of the Pell Grant program.[133][134]

In late 1995, the NCAA concluded that, in addition to the fraudulent Pell Grants facilitated by Russell, the university had also provided or allowed over $400,000 worth of other, improper payments to Miami football players. The NCAA also found that the university had failed to wholly implement its drug testing program, and permitted three football student-athletes to compete without being subject to the required disciplinary measures specified in the policy. The NCAA found that this was evidence that school officials didn't have adequate control over the football program.[135] Miami docked itself seven scholarships as part of a self-imposed sanction in 1995, and the NCAA took away another 24 scholarships over the next two years.

As a result of the scandal, Sports Illustrated's Alexander Wolff wrote a famed and controversial cover story, arguing that Miami should at least temporarily shut down its football program.[133]

On June 21, 1996, Miami football players broke into the apartment of the captain of Miami's track team and struck him repeatedly.[136] In response, Davis suspended three key players for the coming 1996 season,[137] in which the Hurricanes finished 9–3.[138] Davis also suspended two other players who were involved in separate violent incidents.[139]

The low point for Miami came in 1997 when they posted a 5–6 record, the first losing season since Howard Schnellenberger's first year in 1979.[140] The 1997 season saw the Hurricanes suffer one of the program's most humiliating losses, a 47–0 beating at the hands of in-state rival Florida State.[141][142]

The Hurricanes began to reassert themselves in 1998, when they finished 9–3.[143] In late September, Miami was forced to postpone their game with UCLA due to Hurricane Georges.[144] The game was rescheduled for December 5 and for the number 2-ranked Bruins, a trip to the national championship game was at stake. The Hurricanes rebounded from a 66–13 "caning" at the hands of Syracuse quarterback Donovan McNabb[145] to put up over 600 yards of total offense against UCLA en route to a stunning 49–45 victory for the Hurricanes.[146]

The following season carried high hopes and expectations for the Hurricanes. They opened the year with a 23–12 win over Ohio State in East Rutherford.[147] Early success, however, was tempered by tough losses to Penn State[148] and Florida State[100] during a three-game losing streak. The Hurricanes rebounded to win their last four games including a 28–13 win over Georgia Tech in the Gator Bowl.[149]

In 2000, Miami was shut out of the BCS National Championship Game. Despite beating Florida State head-to-head[150] and being ranked higher in both human polls, the Seminoles were chosen to challenge the Oklahoma Sooners for the national championship.[151] The Seminoles were also chosen over Washington, who also had one loss and who had handed Miami its only loss early in the season. Washington had been ranked third or fourth in the human polls, behind Miami. The Hurricanes went into the 2001 Nokia Sugar Bowl as the Big East champions and, after much pregame antics including a brawl between members of the two teams on Bourbon Street in New Orleans, Louisiana,[152] defeated Florida 37–20.[153]

On January 29, 2001, Butch Davis left Miami to become head coach of the NFL's Cleveland Browns.[154]

Larry Coker era (2001–2006)

[edit]After being turned down by Wisconsin head coach Barry Alvarez, athletics director Paul Dee promoted offensive coordinator Larry Coker to head coach to replace Butch Davis.[155]

2001 season and fifth national championship

[edit]Angered at being snubbed by the BCS, the Hurricanes stormed through the 2001 season. They opened the season with a 33–7, nationally televised rout over Penn State in Beaver Stadium.[156] Miami followed up the victory with equally decisive Rutgers,[157] Pittsburgh,[158] and Troy.[159] After building up a 4–0 record, the Hurricanes defeated Florida State in Doak Campbell Stadium, 49–27, ending the Seminoles' 54-game home unbeaten streak.[160] The Hurricanes then defeated West Virginia, 45–3,[161] and Temple, 38–0,[162] before heading to Chestnut Hill to take on Boston College. In the final minute of the fourth quarter, with Miami clinging to a 12–7 lead, Boston College quarterback Brian St. Pierre led the Eagles from their own 30-yard line all the way down to the Hurricanes' 9. With BC on the verge of a momentous upset, St. Pierre attempted a pass to receiver Ryan Read at the Miami 2-yard line. However, the ball deflected off the leg of Miami cornerback Mike Rumph, landing in the hands of defensive end Matt Walters. Walters ran ten yards with the ball before teammate Ed Reed grabbed the ball out of his hands at around the Miami 20-yard line and raced the remaining 80-yards for a touchdown, resulting in an 18–7 Miami victory.[163] After surviving this scare, Miami shutout No. 14 Syracuse, 59–0,[164] and defeated No. 12 Washington, 65–7 in the Orange Bowl.[165] The combined 124–7 score set what the Orlando Sentinel described as an NCAA-record for the largest margin of victory over consecutive ranked opponents.[166][167]

The final hurdle to the 2002 Rose Bowl BCS National Championship Game was at Virginia Tech. Miami jumped on Virginia Tech early, leading 20–3 at halftime, and 26–10 in the fourth quarter. But despite being outgained by the Hurricanes by 134 yards and being dominated in time-of-possession, the Hokies never quit. Virginia Tech added a couple of late touchdowns, attempting two-point conversions on each. The first conversion was successful, pulling them to 26–18, but receiver Ernest Wilford dropped a pass from quarterback Grant Noel in the end zone for the second conversion. Still, the resilient Hokies had one more chance to win the game late, taking possession of the ball at midfield and needing only a field goal to take the lead. But a diving, game-saving interception by Ed Reed sealed the Miami victory, 26–24.[168] Defeating Virginia Tech earned the top-ranked Hurricanes an invitation to the 2002 Rose Bowl to take on BCS No. 2 Nebraska for the national championship.

In the Rose Bowl, the Hurricanes took a 34–0 halftime lead and cruised to a 37–14 win over the Huskers to capture their fifth national championship and put the finishing touches on a perfect 12–0 season.[169] The Miami defense shut down Heisman winner Eric Crouch and the vaunted Huskers offense, holding Nebraska 200 yards below its season average. Ken Dorsey and Andre Johnson were named Rose Bowl co-Most Valuable Players.[170]

Six Hurricane players earned 2001 All-American status and six players were finalists for national awards, including Maxwell Award winner, Ken Dorsey,[171] and Outland Trophy winner, Bryant McKinnie.[172] Dorsey was also a Heisman Trophy finalist, finishing third.[171]

The 2001 Miami Hurricanes are considered by some experts and historians as one of the greatest teams in college football history.[173]

2002 through 2006 seasons

[edit]Miami started the 2002 season as the defending national champion and the No. 1 ranked team in the country.[174] Behind a high-powered offense led by senior quarterback Ken Dorsey, new starting running back Willis McGahee,[175] and a stout defense anchored by Jonathan Vilma,[176] the Hurricanes completed their regular season schedule undefeated. The season was highlighted by a 41–16 win over rival Florida at Ben Hill Griffin Stadium, the first regular season meeting between the rivals since 1987.[177]

The Hurricanes' toughest test was an October clash with in-state rival Florida State at the Orange Bowl. Miami overcame a 13-point second half deficit to defeat the Seminoles, 28–27.[178] The game was clinched when Florida State kicker Xavier Beitia missed a 43-yard field goal, wide left, as time expired.[179] Another signature win came four weeks later when Miami dominated the Tennessee Volunteers, 26–3, before a crowd of 107,745 at Neyland Stadium, considered one of the most hostile road venues in college football.[180] Miami would finish 12–0 and clinch a berth in the Fiesta Bowl BCS National Championship Game after a wild 56–45 victory over Virginia Tech in which McGahee rushed for 205 yards and a school-record six touchdowns.[181] Both Dorsey and McGahee were named as finalists for the Heisman Trophy, finishing 4th and 5th, respectively.[182]

In the midst of a 34-game winning streak, Miami was a 13-point favorite going into the Fiesta Bowl match up against No. 2 Ohio State. The Hurricanes took an early 7–0 lead on a 25-yard touchdown pass from Dorsey to Roscoe Parrish, but Ohio State seized control in the second quarter behind an aggressive pass rush, bolstered by constant blitzing, and a stifling rush defense. The Buckeyes held a 14–7 lead at the half, and a field goal by Mike Nugent extended Ohio State's advantage to 17–7 midway through the third quarter. A touchdown run by McGahee brought the Hurricanes within 3 points, but he suffered a knee injury early in the fourth quarter.[183] Miami was able to fight back and force overtime on a 40-yard field goal by Todd Sievers on the final play of the fourth quarter, aided by several questionable calls. Miami scored a touchdown on its first possession in overtime on a 7-yard pass from Dorsey to Kellen Winslow II, and, on Ohio State's ensuing possession, the Hurricanes appeared to have won the game, 24–17, after Buckeyes quarterback Craig Krenzel's fourth-and-3 pass from the Miami 5 fell incomplete in the end zone. Miami players and coaches rushed the field and stadium fireworks were set off to commemorate the program's apparent sixth national championship. The celebration proved premature.[184] At the conclusion of the play, Big 12 official Terry Porter threw a flag and made a controversial pass interference call against Miami cornerback Glenn Sharpe.[184] The penalty took the air out of Miami's sails and gave Ohio State new life, first-and-goal at the 1.[184] The Buckeyes scored a touchdown to tie it at 24–24 at the end of the first overtime, and Maurice Clarett's 5-yard touchdown run in the second overtime gave Ohio State a 31–24 lead.[184] Miami's ensuing possession saw Dorsey briefly knocked out of the game after a hit from linebacker Matt Wilhelm.[184] After backup quarterback Derrick Crudup completed an 8-yard pass on third down, Dorsey re-entered and converted the crucial fourth-and-3 with a 7-yard completion to Winslow.[184] Miami then drove to the Ohio State 2 yard-line, but was held to one yard on its next three plays, giving Ohio State the national championship.[185]

Miami suffered through some offensive struggles in 2003 behind new quarterback Brock Berlin. A blowout loss at Virginia Tech in early November ended Miami's 39-game regular season winning streak[186] and a loss the following week to Tennessee[187] ended Miami's national championship aspirations. The Hurricanes rebounded to win the Big East Conference championship and finish the season 11–2[188] with a 2004 Orange Bowl victory over Florida State.[189]

Miami joined the ACC in 2004.[190] Despite three conference losses, the Hurricanes ended the season with a Peach Bowl victory over rival Florida.[191]

The 2005 season marked the debut of Kyle Wright as Miami's starting quarterback, although the much-ballyhooed Wright would struggle with consistency during the season with much of Miami's success that year fueled by its defense.[192] After a loss to Florida State after placekick holder Brian Monroe bobbled the snap for what would have been a game-tying field goal attempt,[193] Miami would win eight straight games, including a road win over No. 3 Virginia Tech,[194] only to stumble two weeks later against underdog Georgia Tech.[195] Miami's second conference loss of the season cost it a place in the inaugural ACC Championship game and it competed instead in the Peach Bowl, where it lost to LSU, 40–3.[196]

2005 also saw the program embroiled in more controversy when it was reported several Miami football players had recorded a rap song in 2004 that contained lewd sexual references.[197] The song, recorded by an informal group that called itself "7th Floor Crew" and set to the beat of Aaliyah's "If Your Girl Only Knew". Bomani Jones wrote about the incident a couple of years after the recording.[198]

The Hurricanes went 7–6 during a 2006 season[199] that included an on-field brawl against Florida International,[200] the shooting death of Miami defensive tackle Bryan Pata,[201] and a four-game late-season losing streak. Only a Thanksgiving night victory over Boston College, in Miami's last game of the regular season, saved the Hurricanes from a losing regular season record.[202]

The day following the Boston College victory, university president Donna Shalala fired Coker.[203] Coker coached through the postseason, where he won his final game, a 21–20 victory over Nevada on December 31, 2006, in the MPC Computers Bowl.[204]

Randy Shannon era (2007–2010)

[edit]

After a search that lasted two weeks, Miami athletics director Paul Dee named defensive coordinator Randy Shannon, a starting linebacker on the 1987 national champions, as the Hurricanes' 22nd head coach on December 8, 2006.[205] Shannon reportedly agreed to a four-year deal worth over $4 million.[206] His hiring made him the first African American head coach in Miami football history.[207] One of Shannon's first acts as head coach was to impose a strict code of conduct for the team enacted in large part due to the misbehavior, arrests and shenanigans of Miami players during Larry Coker's tenure as head coach.[208]

Shannon's first year as University of Miami's head coach in 2007 was one of the worst in the Hurricanes' modern history, with the team registering a losing 5–7 record.[209] Under Shannon, the team failed to reach a bowl game for the first time in a decade. Notably, it was the first time in 25 years that the Hurricanes had missed a bowl game with a full complement of scholarships.

Media draft experts considered the freshmen on the 2008 team to be one of the top recruiting classes in the nation.[210] The 2008 season resulted in a 7–6 record.[211] The regular season was highlighted by losses to rivals Florida,[212] and Florida State,[213] and an upset victory over Virginia Tech.[214] The 26–3 loss to Florida was Miami's first in that series since 1985, snapping a 6-game winning streak against the Gators. Afterwards, the tension between the two teams was heightened when Shannon accused Florida coach Urban Meyer of trying to run up the score with an unsuccessful deep pass into the end zone in the game's final minute.[215] The visiting Hurricanes were 221⁄2 point underdogs in the nationally televised game but only trailed 9–3 heading into the fourth quarter, leading some to wonder whether Meyer was trying to compensate for his team's unimpressive performance before kicking a field goal with :25 remaining".[216][217][218]

Miami was knocked out of ACC Championship contention with a late-season loss to Georgia Tech in which the Hurricanes surrendered the second-most rushing yards in school history (472).[219] The Hurricanes finished the 2008 season with a 24–17 loss to California in the Emerald Bowl.[220]

After the 2008 season, Shannon fired offensive coordinator Patrick Nix, citing philosophical differences.[221] Also, starting quarterback Robert Marve left the team because he claimed not to be able to play for Coach Shannon.[222] Shannon placed strict restrictions on Marve's potential transfer destinations and received much criticism in the media.[223][224][225] However, the University of Miami claimed in a press release that the restrictions were set because of suspected tampering by Marve's family or others on behalf of the Marve family.[226]

Shannon's staff suffered more upheaval when defensive coordinator Bill Young left to assume the same position at Oklahoma State, his alma mater, in late January 2009. North Carolina assistant John Lovett was hired to replace him.[227] Shannon hired former UMass head coach Mark Whipple as Miami's new offensive coordinator and associate head coach.[228] Several Miami offensive players from the 2008 season returned, including quarterback Jacory Harris, both starting running backs, most of the offensive line and its top six receivers.[229] Shannon has been able to recruit a number of Southern Florida's top high school football players by telling them that they would be able to play immediately. In fact, 21 true freshmen played during the 2008 season opener.[230]

The 2009 season began on a poor note after two back up quarterbacks, Taylor Cook and Cannon Smith, both transferred out during fall practice, leaving the young Hurricane team with only one serviceable backup in true freshman Alonzo Highsmith Jr..[231] Sophomore Jacory Harris directed the newly implemented offense. To make matters worse, starting defensive end Adewale Ojomo suffered a broken jaw in a locker room fight that led to a season-ending injury, causing the already young Hurricane team to go into their season short handed.[232]

Miami faced a difficult schedule to start the 2009 season with visits to No. 18 Florida State, a home game against No. 15 Georgia Tech, a visit to Lane Stadium and the No. 7 Virginia Tech Hokies and a home visit from the defending Big 12 Conference champions and BCS Champion runners-up in No. 3 Oklahoma.[233] Some national media outlets and sites such as ESPN predicted at best a 2–2 record for the Hurricanes with some even predicting an 0–4 start.[234] Miami opened up their 2009 season against Florida State on Labor Day night for a national broadcast for ESPN. Billed as a "Battle of Rebuilding Programs",[235] Quarterback Jacory Harris led a heroic comeback in Tallahassee to beat the then ranked Seminoles 38–34, overcoming a late interception and apparent injury to Harris in the 4th quarter.[236]

The next week, Miami welcomed the triple option offense of the No. 14 Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets in yet another ESPN prime-time game. Georgia Tech came in hot off of a big ACC win against Clemson University the previous week and held a 4–0 record against the Hurricanes in the last four years, including the previous years pounding in Atlanta. The 2009 contest would be a different story all together, as the Hurricanes handily beat the Jackets 33–17 at home and allowed only 95 rushing yards in the process.[237] The next week, with the Hurricanes in the national spotlight for the first time in 5 years, the No. 9 Miami team visited the No. 11 Virginia Tech Hokies. In pouring rain, Tech defeated the Hurricanes by a final score of 31–7.[238] Beat up and embarrassed, Miami then played Oklahoma. Without Heisman Award winner Sam Bradford,[239] Oklahoma took an early 10–0 lead after two early Jacory Harris interceptions. Going into halftime, the Hurricanes trailed the Sooners 10–7 in a highly contested football game. Miami came out for the second with a huge hit on the kick off team by Cory Nelms that forced the Sooners to start inside their own 20. The following play, sophomore corner Brandon Harris hit Oklahoma Quarterback Landry Jones and forced a fumble that eventually led to a Hurricane touchdown. The momentum stayed with the Hurricanes as they rode to a 21–20 win over the No. 8 team in the country.[240] Following the opening four weeks, Miami was 3–1 and was the talk of sports stations nationwide. Following the gauntlet first third of the season, the Hurricanes won against Florida A&M at home[241] and on the road against in-state foe UCF,[242] moving all the way up to No. 10 in the polls. The Canes then had to take on Clemson in Miami in what was a contest of speed and athleticism. Turnovers, missed opportunities and stand-out back C. J. Spiller led the Tigers to a 40–37 overtime win against the Hurricanes, knocking them out of BCS contention and putting the ACC Championship Game in serious jeopardy.[243]

A win against Wake Forest on Halloween kept the Hurricanes in the conference race,[244] which they followed up on with a 52–17 defeat of Virginia in Miami.[245] The following week North Carolina, led by former Miami head coach Butch Davis, topped Miami 33–24 with an unimpressive performance by Jacory Harris and the offense.[246]

Miami finished the 2009 regular season with back-to-back wins over Duke[247] and in-state opponent South Florida.[248] Miami's final record was 9–3, finishing in 3rd place for the ACC Coastal Division behind Georgia Tech and Virginia Tech.[249] The announcement of the 2009 bowl selections stirred some controversy. Instead of choosing the 3rd best team in the ACC (Miami), Gator Bowl officials chose Florida State to represent the ACC against West Virginia instead of the Hurricanes because of the retirement of legendary FSU coach Bobby Bowden, who served as West Virginia's head coach from 1970 to 1975.[250]

The Hurricanes were relegated to the 2009 Champs Sports Bowl in Orlando, Florida, to play against the 9–3 Wisconsin Badgers.[251] Though the Hurricanes were heavy favorites coming into the contest, the Badgers beat up on the Hurricanes consistently throughout the game. The Hurricanes started off fast with a big return to open the game by Sam Shields, but the Canes just could not maintain any offense throughout the game and had no answer for the power offense of Wisconsin. Going into halftime, the Hurricanes trailed 17–7 and Graig Cooper blew out his knee on the poor turf just before halftime on a kick off return.[252] Though Miami scored a late touchdown and recovered the onside kick, they fell to Wisconsin 20–14 and finished the season at 9–4.[253][254]

After the 2009 season, Shannon signed the No. 13 recruiting class in the nation according to ESPN.[255] Shannon addressed many depth issues including offensive line, line backers and running backs, however the media claimed that the staff missed out on several of the more highly touted recruits on signing day, including a couple of "5 star" players.[256] Coaching changes were made before and after signing day, including the departure of defensive line coach/recruiting coordinator Clint Hurtt to the Louisville[257] and the loss of running backs coach Tommie Robinson to the Arizona Cardinals.[258] Shannon replaced them with former Hurricane and Kentucky defensive line coach Rick Petri[259] and running back coach Mike Cassano from Florida International University.[260] Subsequently, Shannon named wide-receiver coach Aubrey Hill as the recruiting coordinator for the program.[261]

In May 2010, the university raised Shannon's pay and extended his contract as head coach through 2014.[262]

The Hurricanes finished the 2010 season with a 7–6 record,[263] which included losses to rivals Florida State[264] and Virginia Tech[265] and their first ever loss to in-state opponent South Florida in the last game of the season.[266]

Shannon was fired by athletics director Kirby Hocutt after the loss to South Florida.[267] Interim head coach Jeff Stoutland, who was offensive line coach under Shannon, led the team into its 2010 Sun Bowl matchup versus Notre Dame; the Hurricanes lost the New Year's Eve game 33–17.[268][269]

Al Golden era (2011–2015)

[edit]

On December 13, 2010, it was announced that athletics director Kirby Hocutt hired Temple head coach Al Golden as the program's 23rd head coach.[270] Golden was regarded as an up-and-coming coach who had turned around an abysmal Temple football program.[271] Shortly after announcing Golden's hiring, Miami signed Golden to a five-year contract.[272]

In 2011, Golden's first season, the Hurricanes posted a 6–6 record.[273] It was only the third time, since 1979, that the program had failed to register a winning record.[274] The Hurricanes kicked off the season with a 32–24 loss to Maryland.[275] After upsetting No. 17 Ohio State,[276] the Hurricanes lost to Kansas State by a margin of 28–24.[277] Golden's team defeated in-state FCS foe Bethune-Cookman on October 1 by a score of 45–14.[278] After a close 38–35 loss to Virginia Tech,[279] Miami defeated North Carolina by a score of 30–24[280] and No. 20 Georgia Tech by a score of 24–7.[281] The Hurricanes alternated between win and loss for the remainder of the season; losing to Virginia 28–21,[282] defeating Duke 49–14,[283] losing to archrival Florida State 23–19[284] beating South Florida in a 6–3 defensive struggle[285] and losing to Boston College by a score of 24–17.[286]

On November 25, 2011, Miami signed Golden to a raise and four-year contract extension through the 2019 season.[287]

In 2012, the Hurricanes finished with a 7–5 mark.[288] They started the season with a 41–32 victory over Boston College on September 1.[289] After a 52–13 blowout loss to Kansas State,[290]

Golden's team won their next three; defeating Bethune-Cookman 38–10,[291] Georgia Tech 42–36[292] and NC State 44–37.[293] Next, however, the Hurricanes lost their next three, dropping a 41–3 blowout to No. 9 Notre Dame,[294] an 18–14 struggle to North Carolina,[295] and a 33–20 loss to No. 12 Florida State.[296] On November 1, Miami defeated Virginia Tech by a score of 30–12.[297] After a heartbreaking 41–40 loss to Virginia,[298] the Hurricanes won their last two; dominating South Florida 40–9[299] and outlasting Duke by a score of 52–45.[300] This resulted in a three-way tie, with North Carolina and Georgia Tech, for the best record in the ACC Coastal Division. North Carolina, which had defeated the Hurricanes earlier in the season, would have been declared the coastal division champion based on the ACC tie breaker formula.[301] However, due to NCAA sanctions, they were ineligible for postseason play.[301]

Miami finished in second place based on the formula. However, due to likely pending NCAA sanctions from the Nevin Shapiro scandal, the university's administration preemptively chose to forego post-season play for the second consecutive year.[301] Had they played, it would have marked their only appearance in the ACC championship game, since joining the conference, in 2004.[301] It would also have set up a rematch with Florida State, who had defeated the Hurricanes earlier in the season.[301]

The Hurricanes compiled a 9–4 record in 2013.[302] Golden's team came storming out of the gate, winning their first seven; a 34–6 win over in-state opponent Florida Atlantic,[303] a 21–16 win over rival Florida,[304] a 77–7 thrashing of FCS opponent Savannah State,[305] a 49–21 victory over South Florida,[306] a 45–30 win over Georgia Tech,[307] a 27–23 close win over North Carolina[308] and a 24–21 nail biter over Wake Forest.[309] The Hurricanes suffered their first loss of the 2013 season on November 2, losing to No. 3 Florida State in a 41–14 thrashing.[310] Miami dropped a second straight game by way of a 42–24 loss to Virginia Tech[311] and a third consecutive loss to Duke in a 48–30 disappointment[312] dropped the Hurricanes from a No. 7 national ranking to unranked in those three weeks. The Hurricanes were able to close out the regular season with two wins, defeating Virginia 45–26[313] and Pittsburgh 41–31.[314] Miami received a berth in the 2013 Russell Athletic Bowl, a game they lost to No. 18 Louisville in a 36–9 blowout.[315] In October 2013, after an investigation spanning two and a half years, the NCAA announced that "the committee acknowledged and accepted the extensive and significant self-imposed penalties by the university".[316] Therefore, no further bowl ban would be enforced.[317] As a result, Miami was eligible to compete in ACC championship and BCS bowls for the 2013–14 season.[317] However, the NCAA stripped Miami of nine scholarships over three years.[317]

The Hurricanes went 6–7 in 2014.[318] Miami kicked off the season with a 31–13 loss to No. 25 Louisville on September 1.[319] Miami defeated Florida A&M 41–7[320] and Arkansas State 41–20[321] over the next two weeks before losing to No. 24 Nebraska by a score of 41–31.[322] On September 27, the Hurricanes defeated Duke by a margin of 22–10.[323] On October 4, Georgia Tech defeated Miami by a score of 28–17.[324]

Miami won their next three, winning 55–34 over Cincinnati,[325] 30–6 over Virginia Tech[326] and 47–20 over North Carolina.[327] Golden's squad struggled to finish the season, losing their last four; a 30–26 letdown to archrival Florida State,[328] a 30–13 disappointment to Virginia,[329] a 35–23 defeat at the hands of Pittsburgh in the regular season finale[330] and a 24–21 close defeat in the 2014 Independence Bowl in Shreveport, Louisiana, to South Carolina.[331]

The Hurricanes finished 8–5 in 2015.[332] By this time, many Miami fans had grown restless and irritated at the team's inconsistencies and began to call for Golden to be fired using different means, including flying airplanes over Hard Rock Stadium with various "Fire Al Golden" banners.[333] The Hurricanes started the season with a 45–0 shutout of Bethune-Cookman on September 5.[334] A 44–20 win over Florida Atlantic[335] and a 36–33 overtime victory over Nebraska[336] followed before the Hurricanes lost 34–23 to Cincinnati[337] and 29–24 to No. 12 Florida State.[338]

Miami defeated Virginia Tech by a score of 30–20 on October 17 in what would be Al Golden's last win as Miami head coach.[339]

On October 25, 2015, the day after a 58–0 home loss to Clemson,[340] the worst defeat in school history,[341] the university's athletic director Blake James announced Golden's firing.[342] Golden was 32–25 in his five seasons at Miami and led the program to bowl games in 2013 and 2014.[343][344] Tight ends coach Larry Scott finished the season as interim head coach.[345]

In Scott's first game as interim head coach, the Hurricanes recorded a controversial win over Duke.[346] The Hurricanes used eight laterals (reminiscent of the 1982 Cal-Stanford ending) on a kickoff return with no time remaining to score the game-winning touchdown and stun the Blue Devils by a score of 30–27.[347] However, video evidence showed the play should have been blown dead and not counted as a touchdown, as Miami players who possessed the ball on that play's knee were shown to be on the ground more than once.[347] Although the outcome of the game couldn't be changed, the Atlantic Coast Conference subsequently suspended the game and replay officials for failing to catch the errors and make the correct call.[348]

On November 7, Miami defeated Virginia by a score of 27–21.[349] The next week, the Hurricanes lost to No. 17 North Carolina by a score of 59–21.[350] Miami then defeated Georgia Tech 38–21[351] and Pittsburgh 29–24.[352] The Hurricanes received a berth in the 2015 Sun Bowl, a game they lost to Washington State by a score of 20–14.[353]

Mark Richt era (2016–2018)

[edit]

On December 4, 2015, former Georgia head coach Mark Richt was named Miami's 24th head football coach.[354] The hiring generated much excitement and was well-received and praised all across the country.[355][356][357] Although he had recently been fired as head coach of the Bulldogs,[358] Richt achieved great successes during his 15 years as Georgia head coach. His teams represented the SEC in three BCS bowl appearances with a record of 2–1, and finished in the top ten of the final AP Poll seven times (2002–2005, 2007, 2012, 2014). His 2008 team also finished in the top ten of the coaches poll. His Georgia teams averaged about nine wins per season, won two Southeastern Conference championship games and reached four more, reached bowl games each of his 15 seasons as head coach and sent many players to National Football League playing careers.[359]

Richt had prior ties to the Miami football program, having played quarterback for the Hurricanes under Lou Saban and Howard Schnellenberger from 1978 to 1982 and, despite being behind the likes of Jim Kelly, Vinny Testaverde and Bernie Kosar on the depth chart, amassed nearly 1,500 passing yards during his college playing career.[360] Richt also served as offensive coordinator at Florida State from 1994 to 2000 under Bobby Bowden, overseeing an offense that was one of the most potent in the country, won two national championships, and produced two Heisman Trophy winners in Charlie Ward[361] and Chris Weinke.[362][359] Miami signed Richt to a five-year contract worth $4.1 million annually.[363]

The Hurricanes improved to 9–4 in 2016.[364] They began the season on September 3 by blowing out in-state FCS opponent Florida A&M 70–3.[365] The next week, the Hurricanes defeated Florida Atlantic by a score of 38–10.[366] After defeating Appalachian State 45–10,[367] Miami defeated Georgia Tech by a score of 35–21 to record their first Atlantic Coast Conference win under Richt.[368] Then, the Hurricanes embarked upon a four-game losing streak, dropping games to No. 23 Florida State by a score of 20–19,[369] North Carolina by a margin of 20–13,[370] Virginia Tech by a count of 37–16[371] and Notre Dame to the tune of 30–27.[372]

The Hurricanes rebounded to win their last five games of the season, a 51–28 trouncing of Pittsburgh,[373] a 34–14 victory over Virginia,[374] a 27–13 win over NC State[375] and a 40–21 win over Duke with quarterback Brad Kaaya becoming Miami's all-time leading passer to close the regular season.[376] On December 28, 2016, Richt led the Hurricanes to their first bowl win in 10 years, when they defeated No. 16 West Virginia in the 2016 Russell Athletic Bowl by a score of 31–14.[377]

Miami finished 10–3 in 2017.[378] The Hurricanes began the season on September 2, defeating in-state FCS opponent Bethune–Cookman by a margin of 41–13.[379] The Hurricanes were supposed to play Arkansas State on September 9, but the game was canceled due to Hurricane Irma battering the state of Florida that weekend.[380] Although the game was to be played in Jonesboro, Arkansas, the University of Miami administration contended that it would be too difficult for the football team to safely travel in and out of Florida due to the intensity of the hurricane.[381] When Miami refused to reschedule the game and pay the $650,000 they agreed to pay the Red Wolves, the Arkansas State University administration filed a lawsuit seeking the payment.[382] As a result of the cancellation, Miami only played 11 regular season games in 2017 as opposed to the usual 12.[383] Miami also rescheduled their game against Florida State from September 16 to October 7 due to the aftermath of the hurricane.[384]

On September 23, Miami played its second game of the season, defeating Toledo by a score of 52–30.[385] After a 31–6 victory over Duke,[386] Richt's team defeated archrival Florida State by a score of 24–20.[387] After a 25–24 nail biting win over Georgia Tech,[388] the Hurricanes defeated Syracuse by a margin of 27–19.[389] On October 28, Miami defeated North Carolina by a score of 24–19.[390] That was followed by a 28–10 victory over No. 13 Virginia Tech.[391] On November 11, Richt's squad obliterated Notre Dame by a score of 41–8.[392] After a 44–28 win over Virginia,[393] Miami suffered its first loss of the season in the regular season finale, falling to Pittsburgh by a margin of 24–14.[394] In the 2017 ACC Championship Game, Miami was obliterated by No. 1 Clemson by a score of 38–3.[395] The Hurricanes accepted a berth in the 2017 Orange Bowl, a game they lost to No. 6 Wisconsin by a score of 34–24.[396]

On May 3, 2018, the University of Miami administration signed Richt to a five-year contract extension.[397] Miami ended 2018 with another loss to Wisconsin, this time in the Pinstripe Bowl 35–3, finishing 7–6. On December 30, 2018, Richt abruptly announced his retirement from coaching.[398]

Manny Diaz era (2019–2021)

[edit]

The University of Miami hired Manny Diaz as their new head coach on December 30, 2018. A Miami native, Diaz had previously been the team's defensive coordinator the previous three seasons.

Diaz had been hired as head coach by Temple 17 days prior to Richt's retirement. On December 30, 2018, however, Diaz withdrew his commitment to Temple to accept the head coach opportunity at Miami.[399]

Diaz compiled a 21–15 record as head coach during the 2019, 2020, and 2021 seasons. On December 6, 2021, Miami fired Diaz.

Mario Cristobal era (2021–present)

[edit]On December 7, 2021, the University of Miami announced the hiring of Mario Cristobal, a former Miami Hurricanes lineman and member of two University of Miami championship teams in 1989 and 1991, and the former head coach of the University of Oregon, as the new head coach.

In his first season, in 2022, Cristobal had a 5–7 record and brought in a much improved recruiting class.[400] In Cristobal's second season as head coach, in 2023, the team registered a 7–6 record and appeared in the 2023 Pinstripe Bowl at Yankee Stadium, where it lost to Rutgers 31–24.

The 2024 team saw significant improvements over recent years and finished with a 10-3 record, but experienced disappointment after missing out on both the ACC Championship Game and losing the 2024 Pop-Tarts Bowl to Iowa State 42-41.

Conference affiliations

[edit]- Independent (1927–1928)

- Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association (1929–1941)

- Independent (1942–1990)

- Big East Conference (1991–2003)

- Atlantic Coast Conference (2004–present)

Championships

[edit]National championships

[edit]Miami has been selected a winner of a national championship nine times from NCAA-designated major selectors, for which the school officially claims five of them.[401][402] Miami has won five national championships (1983, 1987, 1989, 1991, and 2001), which saw them finish number one in the final AP Poll each time.[403]

| Year | Coach | Selector(s) | Record | Bowl | Result | Final AP | Final Coaches |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1983 | Howard Schnellenberger | AP, FWAA, NFF, UPI (Coaches), USA Today/CNN | 11–1 | Orange | W 31–30 | No. 1 | No. 1 |

| 1987 | Jimmy Johnson | AP, FWAA, NFF, UPI (Coaches), USA Today/CNN | 12–0 | Orange | W 20–14 | No. 1 | No. 1 |

| 1989 | Dennis Erickson | AP, FWAA, NFF, UPI (Coaches), USA Today/CNN | 11–1 | Sugar | W 33–25 | No. 1 | No. 1 |

| 1991 | AP | 12–0 | Orange | W 22–0 | No. 1 | No. 2 | |

| 2001 | Larry Coker | AP, BCS, FWAA, NFF, USA Today/ESPN (Coaches), | 12–0 | Rose (BCS National Championship Game) | W 37–14 | No. 1 | No. 1 |

Claimed national championship

Conference championships

[edit]Miami has won nine conference championships, six outright and three shared.

| Year | Conference | Coach | Overall record | Conf. record |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Big East | Dennis Erickson | 12–0 | 2–0 |

| 1992 | 11–1 | 4–0 | ||

| 1994 | 10–2 | 7–0 | ||

| 1995† | Butch Davis | 8–3 | 6–1 | |

| 1996† | 9–3 | 6–1 | ||

| 2000 | 11–1 | 7–0 | ||

| 2001 | Larry Coker | 12–0 | 7–0 | |

| 2002 | 12–1 | 7–0 | ||

| 2003† | 11–2 | 6–1 |

† Co-champions

Division championships

[edit]Miami has one division championship in the ACC Coastal Division.

| Year | Division | Coach | Opponent | CG result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | ACC Coastal | Mark Richt | Clemson | L 3–38 |

Bowl games

[edit]Miami has played in 43 bowl games with a record of 19 wins and 24 losses in these 43 bowl games. Miami's most common bowl destination has been the Orange Bowl, where they have appeared nine times, compiling a 6–3 overall Orange Bowl record. Miami's most common opponent in bowl play has been Nebraska. The schools have met six times in bowl play with the Hurricanes winning four times and losing twice against the Cornhuskers.

- Recent bowl games

| Date | Bowl | Opponent | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 28, 2013 | Russell Athletic Bowl | Louisville | L 9–36 |

| December 27, 2014 | Independence Bowl | South Carolina | L 21–24 |

| December 26, 2015 | Sun Bowl | Washington State | L 14–20 |

| December 28, 2016 | Russell Athletic Bowl | West Virginia | W 31–14 |

| December 30, 2017 | Orange Bowl (NY6) | Wisconsin | L 24–34 |

| December 27, 2018 | Pinstripe Bowl | Wisconsin | L 3–35 |

| December 26, 2019 | Independence Bowl | Louisiana Tech | L 0–14 |

| December 29, 2020 | Cheez-It Bowl | Oklahoma State | L 34–37 |

| December 28, 2023 | Pinstripe Bowl | Rutgers | L 24–31 |

| December 28, 2024 | Pop-Tarts Bowl | Iowa State | L 42-41 |

Head coaches

[edit]Coaching staff[404]

| Name | Title |

|---|---|

| Mario Cristobal | Head coach |

| Shannon Dawson | Offensive coordinator/quarterbacks coach |

| Lance Guidry | Defensive coordinator |

| Alex Mirabal | Assistant head coach/offensive line coach |

| Joe Salave'a | Defensive Line Coach/Associate head coach – defense/defensive run game coordinator |

| Jahmile Addae | Defensive backs coach |

| Kevin Beard | Wide receivers coach |

| Tim Harris Jr. | Running backs coach |

| Derek Nicholson | Linebackers coach |

| Jason Taylor | Defensive line coach |

| Cody Woodiel | Tight ends coach |

| Aaron Feld | Football strength & conditioning coordinator |

| Mike Rumph | Director/player personnel |

| Alonzo Highsmith | General manager of football operations |

Rivalries

[edit]Florida

[edit]Miami's rivalry with Florida dates back to 1938, making it the oldest rivalry among Florida's "Big Three": the University of Miami, the University of Florida, and Florida State.[405] The Hurricanes defeated the Gators, 19–7, in the first meeting between the geographic rivals.[405] The Seminole War Canoe was carved in 1955 out of a cypress struck by lightning and was given to the winner of the annual football game. The canoe is meant to symbolize the fighting spirit of the Seminole people that is often on display during games between the Hurricanes and Gators. The canoe is now on permanent display at the University of Miami Sports Hall of Fame on the Coral Gables campus.

Miami holds the edge in the all-time series with a 29–26 record against Florida. The two schools met every year from 1944 until 1987, but have not played regularly since then. Florida canceled the annual series after the 1987 season,[406][405] when the requirement of the Southeastern Conference for member schools to play eight conference games induced the University of Florida to fill out the non-conference portion of its schedule with teams that do not require a home-and-home arrangement,[405] except for Florida State.

From 1986 to 2003, Miami won all six of the games between the schools, including victories in the 2001 Sugar Bowl and the 2004 Peach Bowl. Florida snapped its 23-year drought against Miami with a 26–3 win over the Hurricanes in 2008. In 2019, the series resumed with Florida winning 24–20 in the Camping World Kickoff in Orlando, Florida.[407]

They most recently met on August 31, 2024, at Ben Hill Griffin Stadium, Florida's home stadium in Gainesville. Miami delivered a convincing 41–17 victory over the Gators.[408]

Florida State

[edit]Miami's traditional rivals are Florida State[141][142] and Florida.[406][405] Since 2002, the Florida Cup has been awarded to the team that finishes with the best head-to-head record in years when Miami and Florida face each other.[409] To date, six Florida Cups have been awarded with Miami winning the first three.

Miami's rivalry with Florida State dates to 1951 when the Hurricanes defeated the Seminoles 35–13 in their inaugural meeting. The schools have played every year since 1966, with Miami holding the all-time advantage, 33–30. Upon the conclusion of their 2003 regular-season schedules, the teams represented their respective conferences in the 2004 FedEx Orange Bowl (Miami being the champions of the Big East, and Florida State being the champions of the ACC). Miami won the bowl game 16–14; it was the only time the schools have met in post-season football play. The 63 meetings between the teams of FSU and Miami eclipsed the rivalry between the Hurricanes and the Gators (from the University of Florida) following their 2010 game; the series of games between the University of Miami and Florida is Miami's second-longest at 55 games.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the series emerged as one of the premier rivalries in college football.[citation needed] Between 1983 and 2002, the Hurricanes and Seminoles combined to win 7 national championships and play in 14 bowl games with a national championship at stake. The 1988 game starred 57 future NFL pros on the combined rosters. Since 2004, the year Miami left the Big East Conference to join the expanded 12-member Atlantic Coast Conference, the universities have been conference foes, though they are placed in separate divisions within the conference. This alignment creates the potential for the two teams to meet for a second time in the ACC Championship Game, should each win their respective divisions in any particular season. Such a rematch has yet to happen after 14 years of ACC Championship Games, as of 2018.

The series has consistently drawn very high television ratings with the 2006 Miami–Florida State game being the most-watched college football game—regular-season or postseason—in ESPN history, and the 2009 and 1994 meetings being the second- and fifth-most watched regular season games, respectively.[410]

The Miami Hurricanes lead the all-time series 35–32 as of 2022. The most recent meeting was in 2022 on November 5, when the Seminoles won 45–3 in Miami, this is the largest margin of victory in the opposing teams stadium in the series history. Their next scheduled game is November 11, 2023.

Louisville