Mike McCready

Mike McCready | |

|---|---|

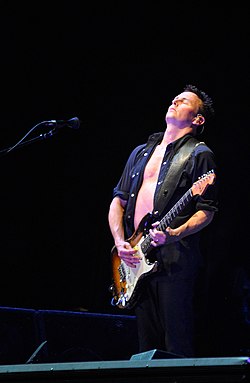

McCready performing with Pearl Jam in 2009 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Michael David McCready |

| Also known as | Petster, McMelty |

| Born | April 5, 1966 Pensacola, Florida, U.S. |

| Origin | Seattle, Washington, U.S. |

| Genres | Alternative rock, grunge, blues rock, hard rock |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter |

| Instrument | Guitar |

| Years active | 1979–present |

| Labels | Monkeywrench, A&M, Epic, Columbia, J |

| Member of | Pearl Jam |

| Formerly of | Temple of the Dog, Mad Season, The Rockfords, Flight to Mars |

| Signature | |

| |

Michael David McCready (born April 5, 1966) is an American musician known for being a founding member and lead guitarist of Pearl Jam. McCready was also a member of the side project bands Flight to Mars, Temple of the Dog, Mad Season, and The Rockfords. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a part of Pearl Jam in 2017 alongside the three other founding members (Jeff Ament, Stone Gossard and Eddie Vedder), and former member Dave Krusen.[1]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Mike McCready was born in Pensacola, Florida, but his family moved to Seattle shortly after his birth.[2] When he was a child, his parents played Jimi Hendrix and Santana; while his friends listened to Kiss and Aerosmith, McCready would frequently play bongo drums.[3] At the age of eleven, McCready purchased his first guitar and began taking lessons.

In eighth grade, McCready formed his first band, Warrior, whose name soon changed to Shadow. Originally a cover band playing during free periods at Roosevelt High School, the band eventually began writing original material and recording demo tapes.[4] After high school, McCready worked at a pizza restaurant where he befriended musician Pete Droge.[5] In 1986, Shadow relocated to Los Angeles and attempted to cut a record deal.[4] However, according to McCready:

We played to a couple bartenders down there, but even though it was a bad scene, it was a good experience. Basically, we weren't that good of a band, and we didn't realize it until we got down there. I guess we lost our focus, got really bummed out and came back to Seattle.[3]

In 1988, Shadow returned to Seattle and split up soon afterwards.[4] McCready lost interest in playing guitar for some time, stating that he was "so depressed about life".[6] He cut his hair, enrolled in a local community college, and spent his nights working at a video store.[3] He credits a friend named Russ Riedner for getting him "out of my college mode and back into playing guitar".[3] McCready was inspired to pick up his guitar again after attending a Stevie Ray Vaughan concert at The Gorge Amphitheatre in George, Washington. McCready said:

As soon as he started "Couldn't Stand the Weather", these huge clouds rolled in overhead, and rain began pouring down. When the song ended, the rain stopped! It was like a religious experience, and it changed me. It lifted me out of the negative mindset I was in, and it got me playing again. I thank him forever for that.[6]

McCready gradually went back to playing guitar and finally joined another band called Love Chile.[3] A childhood friend, Stone Gossard, went to one of the band's shows and appreciated McCready's work after hearing him perform Stevie Ray Vaughan's "Couldn't Stand the Weather".[7] Gossard had known McCready before high school when the two would trade rock band pictures with each other.[3] After the demise of Gossard's band Mother Love Bone, he asked McCready if he wanted to play music together with him.[4] After practicing with Gossard for a few months, McCready encouraged Gossard to reconnect with his fellow Mother Love Bone alum, Jeff Ament.[7]

Temple of the Dog

[edit]The trio were attempting to form their own band when they were invited to be part of the Temple of the Dog project founded by Soundgarden's Chris Cornell as a musical tribute to Mother Love Bone's frontman Andrew Wood, who died of a heroin overdose at age 24. Cornell had been Wood's roommate. The band's line-up was completed by the addition of Soundgarden drummer Matt Cameron.[citation needed]

The band started rehearsing songs that Cornell had written on tour prior to Wood's death, as well as re-working some existing material from demos written by Gossard and Ament.[8] This was McCready's first recording studio experience, and he took a central role in the project. McCready performed an epic four-minute-plus solo for "Reach Down". According to Cornell, McCready's headphone monitors flew off halfway through the recording of the solo, and he played the rest of the solo without being able to hear the backing track.[9] McCready considers this track to be one of his proudest moments.[10] The Temple of the Dog project eventually featured vocalist Eddie Vedder. (Vedder had come to Seattle to audition to be the singer for Ament and Gossard's next band, which later became Pearl Jam.) Vedder sang a duet with Cornell on the song "Hunger Strike" and provided background vocals on several other songs. The band decided that it had enough material for an entire album, and in April 1991 Temple of the Dog was released through A&M Records.[citation needed]

Pearl Jam

[edit]

Pearl Jam was formed in 1990 by Ament, Gossard, and McCready,[11] who then recruited Vedder and drummer Dave Krusen. The band originally took the name Mookie Blaylock, but was forced to change it when the band signed to Epic Records in 1991. After the recording sessions for Ten were completed, Krusen left Pearl Jam in May 1991.[4] Krusen was replaced by Matt Chamberlain, who had previously played with Edie Brickell & New Bohemians. After playing only a handful of shows, one of which was filmed for the "Alive" video, Chamberlain left to join the Saturday Night Live band.[12] As his replacement, Chamberlain suggested Dave Abbruzzese, who joined the group and played the rest of Pearl Jam's live shows supporting the Ten album.

Ten broke the band into the mainstream, and became one of the best-selling alternative albums of the 1990s. The band found itself amidst the sudden popularity and attention given to the Seattle music scene and the genre known as grunge. McCready frequently soloed, and added a blues touch to the music (influenced by Stevie Ray Vaughan). The single "Jeremy" received Grammy Award nominations for Best Rock Song and Best Hard Rock Performance in 1993.[13] Pearl Jam received four awards at the 1993 MTV Video Music Awards for its music video for "Jeremy", including Video of the Year and Best Group Video.[14] Ten was ranked number 207 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time,[15] and "Jeremy" was ranked number 11 on VH1's list of the 100 greatest songs of the '90s.[16]

Following an intense touring schedule, the band went into the studio to record what would become its second studio album, Vs., released in 1993. Upon its release, Vs. set at the time the record for most copies of an album sold in a week,[17] and spent five weeks at number one on the Billboard 200. Vs. was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Rock Album in 1995.[18] From Vs., the song "Daughter" received a Grammy nomination for Best Rock Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal and the song "Go" received a Grammy nomination for Best Hard Rock Performance.[19]

Feeling the pressures of success, the band decided to decrease the level of promotion for its albums, including refusing to release music videos.[20] In 1994, the band began a much-publicized boycott of Ticketmaster, which lasted for three years and limited the band's ability to tour in the United States.[21] Later that same year the band released its third studio album, Vitalogy, which became the band's third straight album to reach multi-platinum status. The album received Grammy nominations for Album of the Year and Best Rock Album in 1996.[22] Vitalogy was ranked number 492 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[15] The lead single "Spin the Black Circle" won a Grammy Award in 1996 for Best Hard Rock Performance.[18] Although Abbruzzese performed on the album Vitalogy, he was fired in August 1994, four months before the album was released.[9] The band cited political differences between Abbruzzese and the other members; for example, he disagreed with the Ticketmaster boycott.[9] He was replaced by Jack Irons, a close friend of Vedder and the former and original drummer of the Red Hot Chili Peppers.[4]

The band subsequently released No Code in 1996 and Yield in 1998. In 1998, prior to Pearl Jam's U.S. Yield Tour, Irons left the band due to dissatisfaction with touring.[23] Pearl Jam enlisted former Soundgarden drummer Matt Cameron as Irons' replacement, initially on a temporary basis,[23] but he soon became a permanent replacement. "Do the Evolution" (from Yield) received a Grammy nomination for Best Hard Rock Performance.[24] In 1998, Pearl Jam recorded "Last Kiss", a cover of a 1960s ballad made famous by J. Frank Wilson and the Cavaliers. It was released on the band's 1998 fan club Christmas single; however, by popular demand, the cover was released to the public as a single in 1999. "Last Kiss" peaked at number two on the Billboard charts and became the band's highest-charting single.

In 2000, the band released its sixth studio album, Binaural, and initiated a successful and ongoing series of official bootlegs. The band released seventy-two such live albums in 2000 and 2001, and set a record for most albums to debut in the Billboard 200 at the same time.[25] "Grievance" (from Binaural) received a Grammy nomination for Best Hard Rock Performance.[26] The band released its seventh studio album, Riot Act, in 2002. Pearl Jam's contribution to the 2003 film, Big Fish, "Man of the Hour", was nominated for a Golden Globe Award in 2004.[27] The band's eighth studio album, the eponymous Pearl Jam, was released in 2006. The band followed it with Backspacer (2009), Lightning Bolt (2013), and Gigaton (2020).

Other musical projects

[edit]Mad Season

[edit]During the production of Vitalogy, McCready went into rehabilitation in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where he met bassist John Baker Saunders of The Lamont Cranston Band.[28] In 1994, when the two returned to Seattle, they formed a side band, The Gacy Bunch, with vocalist Layne Staley of Alice in Chains and drummer Barrett Martin of Screaming Trees. After several live shows, they changed their name to Mad Season. The band released the album Above through Columbia Records in 1995, and are best known for the single "River of Deceit". The band broke up following Saunders' death in 1999 due to a heroin overdose. Staley would pass away three years later in 2002, of an apparent overdose of heroin and cocaine.

On February 28, 2010, McCready performed at the "Hootenanny For Haiti" at the Showbox at the Market in Seattle along with the likes of Velvet Revolver, Jane's Addiction and former Guns N' Roses bassist Duff McKagan, Fastbacks bassist Kim Warnick, Loaded and former Alien Crime Syndicate, Sirens Sister and Vendetta Red bassist Jeff Rouse as well as Truly and former Screaming Trees drummer Mark Pickerel among others.[29][30][31][32]

A number of songs were covered during the show, including Belinda Carlisle's "Heaven Is a Place on Earth",[33] Hank Williams' "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry",[33] The Rolling Stones' "Dead Flowers" among others[33] however one of the more notable covers came when McCready performed a cover of "River of Deceit" for the first time since the breakup of Mad Season[33] with Jeff Rouse performing vocal duties on the song.[33]

Above was re-released in a 3-disc deluxe edition in 2013, and also in vinyl format featuring three new songs with Mark Lanegan on vocals.

In 2015, Live at the Moore 1995 was released on 12" vinyl to coincide with the 20th anniversary of the band's final show. Earlier in 2015, the surviving members, McCready and Martin, joined with the Seattle Symphony in a concert at Benaroya Hall entitled Sonic Evolution featuring special guests and friends. The show was later released on CD/12" vinyl.

Mirror Ball

[edit]McCready performed with other members of Pearl Jam on Neil Young's 1995 album, Mirror Ball, and subsequently took part in an eleven-date tour in Europe as part of Young's backing band. This tour proved very successful with Young's manager Elliot Roberts calling it "One of the greatest tours we ever had in our whole lives".[34]

The Rockfords

[edit]McCready played with another side band called The Rockfords, named after one of McCready's favorite TV shows The Rockford Files. The band features McCready's former high school friends from Shadow, plus vocalist Carrie Akre of Goodness. The band's self-titled debut was released on Epic Records in 2000. In 2021 the band secured the rights to their debut album, and released it on digital platforms in 2022.[35]

Solo album

[edit]In a 2009 interview with San Diego radio station KBZT, McCready revealed that he was working on a solo album.[36]

Walking Papers

[edit]McCready played guitar in the band Walking Papers, which included then-former Guns N' Roses bassist Duff McKagan, Screaming Trees/Mad Season drummer Barrett Martin, and singer Jeff Angell. The band released an album in August 2013.[37][38]

Levee Walkers

[edit]In 2016 a new McCready project involving Duff McKagan, Barrett Martin and Jaz Coleman called The Levee Walkers released two songs on McCready's label HockeyTalkter Records.[39] In 2017 the group released the song "All Things Fade Away" featuring singer Ayron Jones.[40]

Musical style and influences

[edit]

McCready prefers to play "by ear" rather than from a technical standpoint. He stated, "I'm so ignorant of this technical stuff." When asked to explain the intricacies of Pearl Jam's hit-making writing process, McCready says that "I've always done it by ear. Honestly, I'd rather do regular interviews. It's more interesting to talk about whatever… anything other than guitars. I'm not into being a tech-head."[41] McCready's guitar style is usually of an aggressive bluesy nature, and was described by Greg Prato of Allmusic as "feel-oriented" and "rootsy".[42] McCready has cited Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan, David Gilmour, Keith Richards, Pete Townshend and Eddie Van Halen as his biggest musical influences.[43][44][45][46] McCready is also a die-hard Rolling Stones fan, and has described the band as his favorite of all time.[47][48] Additionally, he cites Heart as an influence.[49]

McCready is known to use a Fender Stratocaster, a Gibson Les Paul, and a Gibson Les Paul Junior. When the band started, Gossard and McCready were clearly designated as rhythm and lead guitarists, respectively. The dynamic began to change when Vedder started to play more rhythm guitar during the Vitalogy era. McCready said in 2006, "Even though there are three guitars, I think there's maybe more room now. Stone will pull back and play a two-note line and Ed will do a power chord thing, and I fit into all that."[50] Of his live performances, McCready has said, "I can kind of get into a meditative state when I'm playing, something I don't get any other way ... You might see me staring up in the sky with my eyes closed. I'm not faking it. That just kind of happens."[51]

As time has gone on McCready has contributed more to Pearl Jam's songwriting process. McCready's first writing contribution for Pearl Jam was co-writing the music for the B-side "Yellow Ledbetter" (from the "Jeremy" single), which has since become a regular set closing song during Pearl Jam's live concerts. After co-writing material for Vs. and writing the music for the song "Present Tense" from the album No Code, he wrote the music for three of the tracks on the band's 1998 album, Yield, including one of the band's biggest hits, "Given to Fly". All but one ("Force of Nature", from Backspacer) of McCready's sole compositions for Pearl Jam use alternate tunings, such as open G on "Faithfull" (from Yield), a variation of open D on "Given to Fly", and a variation of open G on "Marker in the Sand" (from Pearl Jam). McCready made his first lyrical contribution for the band with the track "Inside Job", which closes the band's 2006 self-titled album.

Equipment

[edit]McCready is known to use a variety of different guitars, but during Pearl Jam's early years he used mainly Fender Stratocasters. His arsenal now includes Gibson Les Pauls and Gibson Les Paul Juniors, among others.

A Fender Stratocaster has been used constantly and most often throughout his career. McCready has used many types of Stratocasters, vintage and modern, even including left-handed Stratocasters with reversed strings, so that the slanted bridge pickup would have more treble on the lower strings, as opposed to the intended higher strings.[52] This was a common practice of Jimi Hendrix, who played right-handed guitars even though he was left-handed. His most prized model is a slab rosewood fretboard 1960 Stratocaster, the first in a series of 1959 modeled vintage guitars, inspired by Stevie Ray Vaughan's "Number One" guitar.[53] In 2021, Fender Custom Shop master builder Vincent Van Trigt discovered that McCready's valuable 1959 Stratocaster turned out to be a 1960 model. That same year, Fender produced a Custom Shop limited edition of the Mike McCready 1960 Stratocaster which is an accurate replica of McCready's original sunburst.[54][55] In 2023, Fender also produced a Made in Mexico, more affordable signature model of McCready's prized 1960 Stratocaster.[56][57]

McCready's second most used guitar is a Gibson Les Paul. He now uses it for live performances of "Alive", "Brain of J." (from Yield), and "Given to Fly", among others. Among his collection, his most frequently used is his 1959 Standard, formerly owned by Jim Armstrong, guitarist for Van Morrison's band, Them. He has only recently started to use the single pickup Gibson Les Paul Junior, which is a TV yellow 1959 model. He also has Gibson Les Paul Specials. He plays Fender Telecasters on live performances of "Corduroy" (from Vitalogy), "World Wide Suicide" (from Pearl Jam), and "Marker in the Sand", among others.[58] Gibson produced a signature, limited edition version of McCready's 1959 original Les Paul Standard with true historic specifications.[59]

- Amplification [60]

- 65Amps Empire 22-watt head (through a 65Amps 2x12 open-back speaker cab with Celestion G12H30 & Alnico Blue speakers)

- Satellite Atom 36-watt head through a Marshall 260-watt closed-back 4x12 with Celestion Vintage 30s

- 1963 blonde Fender Bassman AB165 through a Savage Audio open-back 2x12 cab

- MXR Custom Audio Electronics MC-404 CAE Wah

- Electro Harmonix Stereo Electric Mistress Flanger

- Xotic EP Boost

- Ibanez TS-9 Tube Screamer Overdrive

- Diamond Compressor

- Line 6 DL-4 Delay

- MXR Uni-Vibe

- Earthquaker Devices Afterneath V2 Reverb

- MXR Carbon Copy Analog Delay

- Electro Harmonix POG2 Polyphonic Octave Generator

- MXR Phase 90 Phaser

- Radial Engineering JX44 Air Control

- MXR/CAE MC-403 Power Distributor

Recognition

[edit]"What's surprising, looking back, is that it was basically jam rock, and Mike McCready's wah-heavy lead guitar was carrying Pearl Jam's mammoth energy, as it still does....If McCready was in a jamband, or not overshadowed by a polarizing, sometimes too-outgoing frontman, he'd probably be carved into the Mt. Rushmore of guitar gods."

In a review of Pearl Jam's 2006 eponymous album, Rolling Stone editor David Fricke admitted that he "screwed up" in excluding both McCready and Pearl Jam rhythm guitarist Stone Gossard from the publication's 2003 feature "The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time".[63] In 2007, McCready's guitar solos from "Alive" and "Yellow Ledbetter" were featured on Guitar World's "100 Greatest Guitar Solos" list.[64] In February 2007, McCready and Gossard were included together by Rolling Stone in its list of "The Top 20 New Guitar Gods" under the title of "four-armed monster"."[65] He was placed at #6 on a list of "The Twenty-Five Most Underrated Guitarists" by Rolling Stone.[66] Adding to that, he was ranked on #1 in Ultimate Guitar's list of the most underrated guitarist of all time.[67] He was also named the highest-paid guitarist in the world, earning a net of more than $82 million in 2021 (though predominantly through avenues other than music).[citation needed] In 2023, McCready and Gossard were both included in Rolling Stone 's "The 250 Greatest Guitarists of All Time" list at #124.[68]

On May 10, 2018, McCready was honored with the Stevie Ray Vaughan Award from MusiCares, for his dedication to and support of MusiCares and his commitment to helping others in the addiction recovery process.[69]

Personal life

[edit]McCready and his wife Ashley O'Connor[70] are the parents of three children. The couple lived in Seattle, Washington as of 2005.[71]

McCready suffers from Crohn's disease, which he was diagnosed with at the age of 21,[72] and has worked to bring awareness of the disease. He endorsed President Barack Obama specifically for his health care program, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act which mandated health insurance be available to those with pre-existing conditions.[73] In 2012, McCready made "Life is a Pre-existing Condition," a video about the importance of nationalized healthcare. McCready performs an annual concert to benefit the Northwest chapter of the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America, and has played at the event in a UFO tribute band called Flight to Mars as well as a reunited Shadow line-up.[51]

McCready's favorite literary author is John Steinbeck and his favorite book of all time is The Grapes of Wrath.[74]

McCready is also an avid sports fan and a lifelong supporter of Seattle Seahawks, Seattle Mariners and Seattle Sounders FC.[75][76][77][78]

Substance abuse

[edit]Like many others from the Seattle grunge scene, McCready has had two different bouts with substance abuse. The first came during the production of Pearl Jam's 1994 album Vitalogy, when McCready was fighting drug and alcohol addiction:[28]

We had a lot of meetings where they would say, 'Hey Mike, you're getting way too fucked up.' But we're all really good friends and we love each other and I think they actually thought I was going to die, but they never took steps to kick me out of the band, which I can't believe because I fucked up so many times. I was drunk and making an ass out of myself and they were concerned about it. ... I'd clean up for a little while then I'd fall off the wagon, like addicts do. ... When everything blew up, everybody kind of lost their minds. ... I was clean for about a month ... well, semi-clean; I can't bullshit about that ... but I fell off the wagon after the Kurt Cobain thing. That fucked with everybody really hard. I mean, how do you get to that point of depression where suicide's the only way out?[28]

McCready's second bout came during the sessions for Pearl Jam's 2000 album Binaural:

I was going through some personal problems. It was my own stuff I was dealing with. That was a tough time. I was out of it. That was due, at the time, I was taking prescription drugs. I got caught up in it, because of my pain.[9]

Charity contributions

[edit]McCready was a part of the effort to raise money for Roger Federer's charity, Roger Federer Foundation as a part of Match for Africa – a non competitive tennis event held to a packed Key Arena in Seattle on April 29, 2017. In this event, McCready teamed with John Isner, and competed against Roger Federer and philanthropist Bill Gates. Federer and Gates won the game 6–4.[79] McCready also donates to the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation regularly, participating in their flag football tournaments.

Photography

[edit]In 2017, McCready published a book of Polaroids he shot during his time in Pearl Jam, dating back to the early 1990s. Titled Of Potato Heads and Polaroids: My Life Inside and Out of Pearl Jam, and published by powerHouse books, McCready described the book as "an emotional ride".[80] The photos in it document the band on tour, fellow musicians including Neil Young, Dave Grohl, Joey Ramone, and Jimmy Page, and McCready's personal life.[81]

Discography

[edit]- Temple of the Dog discography

| Year | Title | Label |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Temple of the Dog | A&M |

- Pearl Jam discography

- Mad Season discography

| Year | Title | Label | Track(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | Above | Columbia | All |

| Working Class Hero: A Tribute to John Lennon | Hollywood | "I Don't Wanna Be a Soldier" | |

| 1996 | Bite Back: Live at Crocodile Cafe | PopLlama | "River of Deceit" (live) |

| 2013 | Above (Deluxe Edition) | Columbia/Legacy | |

| 2015 | Live at the Moore 1995 | Columbia/Legacy | |

| 2015 | Seattle Symphony- Sonic Evolution (Live at Benaroya Hall) | Monkeywrench Records |

- The Rockfords discography

| Year | Title | Label | Track(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Down to You: Music from the Miramax Motion Picture | Epic | "Silver Lining" |

| The Rockfords | Epic | All | |

| 2003 | Live Seattle, WA 12/13/03 | Kufala | All |

| 2004 | Waiting... | Ten Club | All |

- Contributions and collaborations

| Year | Artist(s) | Title | Label | Track(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | Lazy Susan | Twang | Silver Eye | "Bored" |

| 1993 | Eddie Vedder and Mike McCready with G. E. Smith | The 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration | Sony | "Masters of War" (live) |

| M.A.C.C. (Mike McCready, Jeff Ament, Matt Cameron, and Chris Cornell) | Stone Free: A Tribute to Jimi Hendrix | Reprise/WEA | "Hey Baby (Land of the New Rising Sun)" | |

| 1995 | Neil Young | Mirror Ball | Reprise | All |

| 1996 | Goodness with Mike McCready (as Petster) | Schoolhouse Rock! Rocks | Rhino/WEA | "Electricity, Electricity" |

| $10,000 Gold Chain (MariAnn Braeden of Green Apple Quick Step with Mike McCready) | The Cable Guy: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | Sony | "Oh! Sweet Nuthin'" | |

| Screaming Trees | Dust | Epic | "Dying Days" | |

| 1997 | Tuatara | Breaking the Ethers | Epic | "The Getaway" |

| Mark Eitzel | West | Warner Bros. | "Fresh Screwdriver" | |

| The Minus 5 | The Lonesome Death of Buck McCoy | Hollywood | Some | |

| Brad | Interiors | Sony | "The Day Brings" | |

| Eddie Vedder and Mike McCready | Tibetan Freedom Concert | Capitol | "Yellow Ledbetter" (live) | |

| 1999 | Goodness | These Days | Good-Ink | "Catching Fireflies" |

| 2000 | Stillwater | Almost Famous: Music from the Motion Picture | DreamWorks | "Fever Dog" |

| 2001 | Eddie Vedder and Mike McCready with Neil Young | America: A Tribute to Heroes | Interscope | "Long Road" (live) |

| 2002 | The Wallflowers | Red Letter Days | Interscope | "When You're on Top", "Everybody Out of the Water", "Too Late to Quit", "See You When I Get There", and "Everything I Need" |

| 2003 | Mike McCready, Stone Gossard, Cole Peterson, and Chris Friel | Live from Nowhere Near You | Funkhead Music | "Powerless" |

| 2004 | Heart | Jupiters Darling | Sovereign | "I'm Fine" |

| 2005 | Screaming Trees | Ocean of Confusion: Songs of Screaming Trees 1989–1996 | Epic | "Dying Days" |

| 2006 | Peter Frampton | Fingerprints | A&M | "Black Hole Sun" and "Blowin' Smoke" |

| 2008 | Kristen Ward | Drive Away | Mutt Moan Music | "With You Again" |

| 2009 | Dierks Bentley | Feel That Fire | Capitol Nashville | "Life on the Run" |

| The Wallflowers | Collected: 1996–2005 | Interscope | "When You're on Top" | |

| 2010 | Mike McCready | Fringe | — | "Northwest Passage" |

| 2011 | Tres Mts. | Three Mountains | Monkeywrench | various |

| 2012 | Soundgarden | King Animal | Universal Republic | "Eyelid's Mouth" |

| 2016 | Nando Reis | Jardim-Pomar | Relicário | "Pra onde foi" |

| 2022 | Ozzy Osbourne | Patient Number 9 | Epic | "Immortal" |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Inductees: Pearl Jam". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ The Rock FM. Mike McCready interview on The Rock radio station The Rock. November 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Rotondi, James. "Blood On the Tracks". Guitar Player. January 1994.

- ^ a b c d e f Greene, Jo-Ann. "Intrigue and Incest: Pearl Jam and the Secret History of Seattle" (Part 2). Goldmine. August 20, 1993.

- ^ Alvarez, Tina. "Pete Droge". EMOL Music. 1996.

- ^ a b Aledort, Andy. "Aural Exam" Archived February 10, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Guitar World. July 2000.

- ^ a b Hiatt, Brian (June 16, 2006). "The Second Coming of Pearl Jam". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ^ Alden, Grant. "Requiem for a Heavyweight." Guitar World. July 1997

- ^ a b c d Weisbard, Eric, et al. "Ten Past Ten" Spin. August 2001.

- ^ Gilbert, Jeff. "Prime Cuts: Mike McCready – The Best of Pearl Jam!". Guitar School. May 1995.

- ^ Crowe, Cameron (October 28, 1993). "Five Against the World". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 19, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ^ Peiken, Matt (December 1993). "Dave Abbruzzese of Pearl Jam". Modern Drummer. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ^ "Clapton Tops List of Grammy Nominations". The Seattle Times. January 7, 1993. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ "1993 Video Music Awards". MTV.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ a b "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 14, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- ^ "VH1: 100 Greatest Songs of the '90s". VH1. Archived from the original on December 16, 2007. Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ^ Hajari, Nisid (November 19, 1993). "Pearl's Jam". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2007.

- ^ a b "Awards Database". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (February 26, 1995). "POP VIEW; Playing Grammy Roulette". The New York Times. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ Ashare, Matt. "The Sweet Smell of (Moderate) Success". CMJ. July 2000.

- ^ DeRogatis, Jim. Milk It!: Collected Musings on the Alternative Music Explosion of the 90's. Cambridge: Da Capo, 2003. ISBN 0-306-81271-1, pg. 58

- ^ Strauss, Neil (January 5, 1996). "New Faces in Grammy Nominations". The New York Times. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ a b Fischer, Blair R (April 17, 1998). "Off He Goes". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 2, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- ^ "41st annual Grammy nominees and winners". CNN.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2008. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ Davis, Darren (March 7, 2001). "Pearl Jam Breaks Its Own Chart Record". Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on September 12, 2006. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- ^ Moss, Corey. "Pearl Jam DVD Compiles Tour Footage". MTV.com. Archived from the original on February 23, 2001. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ "Golden Globes Nominations & Winners". goldenglobes.org. Archived from the original on February 1, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2008.

- ^ a b c Gilbert, Jeff. "Alive-Pearl Jam's Mike McCready Says Goodbye to Drugs and Alcohol and is a Better Man For it". Guitar World. April 1995.

- ^ "DUFF MCKAGAN, MIKE MCCREADY Perform At 'A Hootenanny For Haiti'; Video, Photos Available". Blabbermouth.net. March 3, 2010. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012.

- ^ "Mike McCready Plays "A Hootenany for Haiti" February 28th at Seattle's Showbox at the Market". PearlJam.com. January 27, 2010. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ "A Hootenanny For Haiti > Showbox at the Market". Seattle Theatre Group. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ "Showbox at the Market". Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Hay, Travis (March 1, 2010). "A three-hour jam session with some of Seattle's finest musicians". Crosscut.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ McDonough, Jimmy. "Shakey: Neil Young's Biography", Anchor, 2003. ISBN 0-679-75096-7 [1]

- ^ Uitti, Jacob (January 12, 2021). "22-Year-Old Side Project from Pearl Jam's Mike McCready Gets New Digital Release". American Songwriter.

- ^ "Listen to Mike McCready Interview Where He Talks About Possible Pearl Jam EP". grungereport.net. July 20, 2009. Archived from the original on July 26, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ Steven Hyden (August 3, 2012). "Seattle Supergroup Walking Papers: Duff N' McCready N' Screaming Trees Jam". grandland.com. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ "Debut Album Available Now". Walking Papers. Archived from the original on October 2, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Giles, Jeff (April 25, 2016). "Hear a Pair of Songs From Duff McKagan and Mike McCready's Levee Walkers Project".

- ^ Ryan Reed (November 2, 2017). "Guns N' Roses, Pearl Jam Supergroup the Levee Walkers: Hear Cathartic New Song". Rolling Stone.

- ^ "Mike McCready breaks down the gear and inspiration behind 15 landmark Pearl Jam tracks". October 28, 2022.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "Mike McCready > Biography". Allmusic. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ "Limited Edition Mike McCready 1960 Stratocaster® | Limited Edition Series | Fender® Custom Shop". Fendercustomshop.com. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "Mike McCready on the Influence of Jimi Hendrix | MoPOP | Museum of Pop Culture". April 5, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Mike McCready Limited Edition 1960 Stratocaster | Fender Custom Shop | Fender". April 8, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ ""I loved Hendrix – he was my first guitar hero... But seeing Stevie Ray Vaughan was transcendent. He made me understand Hendrix better": Mike McCready says SRV helped him make sense of this Hendrix technique". December 8, 2023.

- ^ "Sad to hear of Charlie Watts passing. The Rolling Stones have always been my favorite band, and Charlie was the engine of subltle and heavy grooves. I'll put on "Sway" which is my favorite song of all time. Any of us in a rock band wouldn't be here if it hadn't been for Charlie". Twitter.com. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "Mike McCready | Vintage Guitar® magazine". June 13, 2022.

- ^ Edgers, Geoff (May 16, 2024). "How do you mend a broken Heart? Ann and Nancy Wilson know". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Cross, Charles R. "Better Man". Guitar World Presents: Guitar Legends: Pearl Jam. July 2006.

- ^ a b Brownlee, Clint. "McCready On Another Flight to Mars" Archived June 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. seattlesoundmag.com. May 1, 2008.

- ^ "Influences" Archived June 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. giventowail.com.

- ^ "Mike McCready's 1959 Guitars". Youtube.com. November 14, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ "Limited Edition Mike McCready 1960 Stratocaster® | Limited Edition Series | Fender® Custom Shop". Fendercustomshop.com. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ April 2021, Matt Owen 08 (April 8, 2021). "Fender launches limited-edition Mike McCready 1960 Stratocaster". Guitarworld.com. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mike McCready Stratocaster®".

- ^ ""I'm honored to deliver a more approachable guitar to the next generation of players": Fender makes Mike McCready's iconic 1960 Stratocaster accessible to the masses with new signature model". September 12, 2023.

- ^ "Corduroy - Let's Play Two - Pearl Jam - YouTube". Youtube.com. September 26, 2017. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ "Mike McCready 1959 Les Paul Standard". Legacy.gibson.com. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ a b "Interview: Mike McCready on Mad Season Reissue and New Pearl Jam". Premier Guitar. March 6, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "Pearl Jam's Mike McCready Teaches You How to Play "Alive!" Solo | Shred with Shifty". YouTube. November 9, 2023.

- ^ Adam Perry (November 14, 2014). "The 10 Most Underrated Guitarists in the History of Rock". City Pages. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Fricke, David. "Pearl Jam: Review". Rolling Stone. April 21, 2006.

- ^ "100 Greatest Guitar Solos" Archived March 5, 2016, at archive.today. Guitar World. 2007.

- ^ Fricke, David. "The Top 20 New Guitar Gods". Rolling Stone. February 22, 2007.

- ^ "The Twenty-Five Most Underrated Guitarists". Rolling Stone. October 1, 2007.

- ^ "Top 20 Most Underrated Guitarists". Ultimate-guitar.com. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "The 250 Greatest Guitarists of All Time". Rolling Stone. October 13, 2023.

- ^ "Pearl Jam's Mike McCready To Be Honored At 2018 MusiCares Concert For Recovery". Grammy.com. March 8, 2018. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ "Media Advisory: Pearl Jam's Mike McCready to Testify in Support of Restroom Access Bill". housedemocrats.wa.gov. January 28, 2009. Archived from the original on July 19, 2009. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ^ Brodeur, Nicole (April 5, 2005). "Pearl Jam's McCready Speaks from the Gut". The Seattle Times. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ^ Chang, Young. "Pearl Jam Guitarist to Tell of Life With Crohn's". The Seattle Times. May 13, 2003.

- ^ "A Conversation with Pearl Jam Guitarist Mike McCready". healthtalk.com. June 25, 2004.

- ^ "Pearl Jam pick their favourite books of all time". Faroutmagazine.com. July 13, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "2019 Week 7: 12 Flag Raiser - Guitarist Mike McCready Interview".

- ^ "Mike McCready's National Anthem | 09/08/2017". MLB.com.

- ^ "Mike McCready performs the Star Spangled Banner". YouTube. November 12, 2014.

- ^ "Pearl Jam's Mike McCready Plays National Anthem at Mariners vs. Tigers Baseball Game". Loudwire. October 5, 2022.

- ^ Bean, Sy (April 29, 2017). "Photos: Roger Federer & Bill Gates play doubles charity match at Key Arena". Seattle Refined. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Pearl Jam's Mike McCready Talks About His New Book 'Of Potato Heads and Polaroids'". Format.com. May 10, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "Of Potato Heads and Polaroids: My Life Inside and Out of Pearl Jam | powerHouse Books". Powerhousebooks.com. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch