Hongwu Emperor

| Hongwu Emperor 洪武帝 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

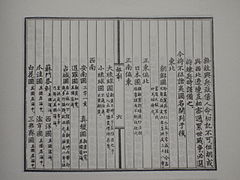

A Seated Portrait of Ming Emperor Taizu, c. 1377[1] by an unknown artist from the Ming dynasty. Now located in the National Palace Museum, Taipei | |||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Ming dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 23 January 1368[a] – 24 June 1398 | ||||||||||||||||

| Enthronement | 23 January 1368 | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Jianwen Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of China | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1368–1398 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Toghon Temür (Yuan dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Jianwen Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Born | Zhu Chongba (朱重八) 21 October 1328[b] Hao Prefecture, Henan Jiangbei (present-day Fengyang County, Anhui)[2][3][4] | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | 24 June 1398 (aged 69) Ming Palace, Zhili (present-day Nanjing) | ||||||||||||||||

| Burial | 30 June 1398 Ming Xiaoling, Nanjing | ||||||||||||||||

| Consort | |||||||||||||||||

| Issue |

| ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| House | Zhu | ||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Ming | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Zhu Shizhen | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Chun | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||||||

| Hongwu Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 洪武帝 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Vastly Martial Emperor | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The Hongwu Emperor (21 October 1328 – 24 June 1398),[b] also known by his temple name as the Emperor Taizu of Ming (明太祖), personal name Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋; Chu Yüan-chang), courtesy name Guorui (國瑞; 国瑞), was the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1368 to 1398.[8]

Zhu Yuanzhang was born in 1328 to a family of impoverished peasants. As famine, plague, and peasant revolt surged across China proper during the 14th century,[9] Zhu rose to command the Red Turban Rebellion that conquered China proper, ending the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty and forcing the remnant Yuan court (known as Northern Yuan in historiography) to retreat to the Mongolian Plateau. He claimed the Mandate of Heaven and established the Ming dynasty at the beginning of 1368[10] and occupied the Yuan capital of Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing), with his army that same year. Trusting only his family, he made his many sons feudal princes along the northern marches and the Yangtze valley.[11] Having outlived his eldest son Zhu Biao, the Hongwu Emperor enthroned his grandson as the Jianwen Emperor via a series of instructions. This ended in failure when the Jianwen Emperor's attempts to unseat his uncles led to the Jingnan Rebellion.[12]

The era of Hongwu was noted for its tolerance of minorities and religions; the Chinese historian Ma Zhou indicates that the Hongwu Emperor ordered the renovation and construction of many mosques in Xi’an and Nanjing.[13] Wang Daiyu also recorded that the emperor wrote the Hundred-word Eulogy praising Islam.[13]

The reign of the Hongwu Emperor is notable for his unprecedented political reforms. The emperor abolished the position of chancellor,[14] drastically reduced the role of court eunuchs, and adopted draconian measures to address corruption.[15] He also established the Embroidered Uniform Guard, one of the best known secret police organizations in imperial China. In the 1380s and 1390s, a series of purges were launched to eliminate his high-ranked officials and generals; tens of thousands were executed.[16] The reign of Hongwu also witnessed much cruelty. Various cruel methods of execution were introduced for punishable crimes and for those who directly criticized the emperor, and massacres were also carried out against everyone who resisted his rule.[17][18][19][20][21][excessive citations]

The emperor encouraged agriculture, reduced taxes, incentivized the cultivation of new land, and established laws protecting peasants' property. He also confiscated land held by large estates and forbade private slavery. At the same time, he banned free movement in the empire and assigned hereditary occupational categories to households.[22] Through these measures, the Hongwu Emperor attempted to rebuild a country that had been ravaged by war, limit and control its social groups, and instill orthodox values in his subjects,[23] eventually creating a strictly regimented society of self-sufficient farming communities.[24]

Early life

[edit]Zhu was born to a family of impoverished tenant farmers in Zhongli County in present-day Fengyang, Anhui.[25][26] His father's name was Zhu Shizhen (朱世珍, original name Zhu Wusi 朱五四) and his mother was Chen Erniang. He had seven older siblings, several of whom were "given away" by his parents, as they did not always have enough food to support the family.[27] When he was 16, severe drought ruined the harvest where his family lived, and famine subsequently killed everyone in his family except for him and one of his brothers. He then buried them by wrapping their bodies in white cloth.[28]

Zhu's grandfather, who lived to be 99 years old, had served in the Southern Song army and navy, which had fought against the Mongol invasion, and told his grandson tales of it.[29]

Destitute after his family's death, Zhu accepted a suggestion to take up a pledge made by his brother and became a novice monk at the Huangjue Temple,[30] a local Buddhist monastery. However, he was forced to leave the monastery after it ran short of funds.

For the next few years, Zhu led the life of a wandering beggar and personally experienced the hardships of the common people during the late years of the Yuan dynasty.[31] After about three years, he returned to the monastery and stayed there until he was around 24 years old. He learned to read and write during the time that he spent with the Buddhist monks.[32]

Rise to power

[edit]

The monastery where Zhu lived was eventually looted and destroyed by an army whose task was supposedly to suppress a local rebellion.[33] In 1352, Zhu joined one of the many insurgent forces that had risen in rebellion against the Yuan.[34] He rose rapidly through the ranks and became a commander. His forces later joined the Red Turbans, a millenarian sect related to the White Lotus Society, then led by Han Shantong. The Red Turbans followed cultural and religious traditions of Buddhism, Manichaeism and other religions. Widely seen as a defender of Confucianism and neo-Confucianism among the predominant Han population in China proper, Zhu emerged as a leader of the rebels that were struggling to overthrow the Yuan dynasty.

In 1356, Zhu and his army conquered Nanjing,[35] which became his base of operations and later the capital of the Ming dynasty during his reign. Zhu's government in Nanjing became famous for good governance, and the city attracted vast numbers of people fleeing from other more lawless regions. It is estimated that Nanjing's population increased tenfold over the next 10 years.[36] In the meantime, the Yuan government had been weakened by internal factions fighting for control, and it made little effort to retake the Yangtze River valley. By 1358, central and Southern China had fallen into the hands of different rebel groups. During that time the Red Turbans also split up. Zhu became the leader of a smaller faction (called "Wu" around 1360), while the larger faction, under Chen Youliang, controlled the center of the Yangtze River valley.[37]

Zhu Yuanzhang was the Duke of Wu, which was nominally under the control of Han Shantong's son Han Lin'er (韓林兒), who was enthroned as the Longfeng Emperor of the Song dynasty.[38]

Zhu was able to attract many talents into his service. One of them was Zhu Sheng (朱升), who advised him to "build high walls, stock up rations, and delay claiming kingship" (Chinese: 高築牆、廣積糧、緩稱王).[39] Another, Jiao Yu, was an artillery officer, who later compiled a military treatise outlining the various types of gunpowder weapons.[40] Another one, Liu Bowen, became one of Zhu's key advisors, and edited the military-technology treatise titled Huolongjing in later years.

Beginning in 1360, Zhu and Chen Youliang fought a protracted war for supremacy over the former territories controlled by the Red Turbans. The pivotal moment in the war was the Battle of Lake Poyang in 1363. The battle lasted three days and ended with the defeat and retreat of Chen's larger navy.[41] Chen died a month later in battle. Zhu did not participate personally in any battles after that and remained in Nanjing, where he directed his generals to go on campaigns.

In 1367, Zhu's forces defeated Zhang Shicheng's Wu regime, which was centered in Suzhou and had previously included most of the Yangtze delta, and Hangzhou, which was formerly the capital of the Song dynasty.[42][43] This victory granted Zhu's government authority over the lands north and south of the Yangtze River. The other major warlords surrendered to Zhu and on 23 January 1368, Zhu proclaimed himself emperor of the Ming dynasty in Nanjing and adopted "Hongwu" (lit. "vastly martial") as his era name.[44]

In 1368, Ming armies headed north to attack territories that were still under Yuan rule. Toghon Temür (Emperor Shun of Yuan) gave up the capital Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing), and the rest of northern China in September 1368 and retreated to the Mongolian Plateau. On 15 October 1371, one of Hongwu's sons, Zhu Shuang, was married to the sister of Köke Temür, a Bayad general of the Yuan dynasty.[45][46][47]

In 1371, the Ming dynasty defeated the Ming Xia founded by Ming Yuzhen, which ruled Sichuan.[48]

The Ming army captured the last Yuan-controlled province of Yunnan in 1381, and China proper was unified under Ming rule.[49]

Reign

[edit]

Under Hongwu's rule, Mongol and other foreign bureaucrats who had dominated the government during the Yuan along with Northern Chinese officials were replaced by Han officials. The emperor re-instituted, then abolished, then restored, the Confucian civil service imperial examination system, from which most state officials were selected based on their knowledge of literature and philosophy. The Ming examination curriculum followed that set by the Yuan in 1313: a focus on the Four Books over the Five Classics and the commentaries of Zhu Xi.[50] The Confucian scholar-bureaucrats who had been previously marginalized during the Yuan dynasty were reinstated to their predominant roles in the government.

"Barbarian" (i.e. Mongol-related) elements, including garments and names, were made illegal. There was no clear definition on what was "barbarian", and individual clothing styles and names were banned at the emperor's will.[51] There were also attacks on palaces and administrative buildings previously used by the rulers of the Yuan dynasty.[52] But many of Taizu's government institutions were actually modeled on those of the Yuan dynasty: community schools required for primary education in every village.[53]

Ming's legal system established by Hongwu contains various methods of execution including flaying, and slow slicing.[17][18][19] One of his generals, Chang Yuchun, carried out massacres in Shandong and Hunan to take revenge against people who resisted his army.[20] Over time, Hongwu became increasingly fearful of rebellions and coups, and also ordered the execution of those of his advisors who criticized him.[21] Manicheanism and the White Lotus Sect, which played significant roles during the revolts against the Yuan, were outlawed.[54] He was also said to have ordered the massacre of several thousand people living in Nanjing after having heard one talked about him without respect.[55][56][57] In the Hu Weiyong case alone, tens of thousands of officials and their families were executed over sedition, treason, corruption and other charges.[58][59][60] According to an anecdote noted by Ming dynasty writers, in 1380, after much killing, a lightning bolt struck his palace and he stopped the massacres for some time, as he was afraid divine forces would punish him.[61] In the 1390s, however, tens of thousands more people were executed due to their association with an alleged plot of rebellion by general Lan Yu.[62]

After the Ming were established, Hongwu's military officers were given noble titles. These privileged the holder with a stipend, but in all other aspects was merely symbolic.[63] Mu Ying's family was among them.[64][65][66][67][68] Special rules against abuse of power were implemented on the nobles.[69]

Land reforms

[edit]As Hongwu came from a peasant family, he was aware of how peasants used to suffer under the oppression of the scholar-bureaucrats, and the wealthy. Many of the latter, relying on their connections with government officials, encroached unscrupulously on peasants' lands and bribed the officials to transfer the burden of taxation to the poor. To prevent such abuse, he instituted two systems: Yellow Records and Fish Scale Records. They served both to secure the government's income from land taxes and to affirm that peasants would not lose their lands.

However, the reforms did not eliminate the threat of the bureaucrats to peasants. Instead, the expansion of the bureaucrats and their growing prestige translated into more wealth, and tax exemption for those in the government service. The bureaucrats gained new privileges, and some became illegal money-lenders and managers of gambling rings. Using their power, the bureaucrats expanded their estates at the expense of peasants' lands through outright purchase of those lands, and foreclosure on their mortgages whenever they wanted the lands. The peasants often became either tenants, or workers, or sought employment elsewhere.[70]

Since the beginning of the Ming dynasty in 1357, great care was taken by Hongwu to distribute land to peasants. One way was by forced migration to less-dense areas.[71] Hongtong County, for example, was the source of many of those migrants due to its particularly dense population. The migrants were gathered under a pagoda tree (洪洞大槐樹) and escorted to neighboring provinces. "The great pagoda tree in Hongtong, Shanxi" became a common idiom when referring to one's ancestral home in certain areas of Henan and Hebei.[72] Public works projects, such as the construction of irrigation systems, and dikes, were undertaken in an attempt to help farmers. In addition, Hongwu also reduced the demands for corvée labor on the peasantry.

In 1370, Hongwu ordered that some lands in Hunan and Anhui should be given to young farmers who had reached adulthood. The order was intended to prevent landlords from seizing the land, as it also decreed that the titles to the lands were not transferable. During the middle part of his reign, he passed an edict, stating that those who brought fallow land under cultivation could keep it as their property without being taxed. The policy was well received by the people and in 1393, cultivated land rose to 8,804,623 qing and 68 mu, something not achieved during any other Chinese dynasty.[citation needed] Hongwu also instigated the planting of 50 million trees in the vicinity of Nanjing, reconstructing canals, irrigation, and repopulation of the North.[73]

Social policy

[edit]Under the Hongwu reign, rural China was reorganized into li (里), communities of 110 households. The position of community chief rotates among the ten most populous households, while the rest were further divided into tithings. Together, the system was known as lijia. The communities were responsible for collecting tax and drafting labor for the local government. Village elders were also obliged to keep surveillance on the community, report criminal activities, and ensure that the residents are fully committed to agricultural work.[74][75]

The Yuan dynasty Zhuse Huji (諸色戶計) system was continued and the households were categorized into different types. The most basic types, namely civilian households (民戶), military households (軍戶), craftsmen households (匠戶) and salt worker households (鹽灶戶), defined the family's form of corvée labor. Military households, for example, accounted for around one-sixth of the total population at the beginning of the Yongle era, and each was required to provide an adult man as soldier, and at least one more person to work in support roles in the military. The military, craftsmen and salt worker households were hereditary, and converting into civilian households was impossible except in a few very rare situations.[76][77] A family may simultaneously belong in one of the minor categories, e.g. physician households and scholar households, according to their occupation. In addition to the aforementioned "good" households, discriminatory types also existed, such as entertainer households (樂戶).[78]

Travelers were required to carry a luyin (路引), a permit issued by the local government, and their neighbors were required to have knowledge of their itinerary. Unauthorized domestic migration was banned, and offenders were exiled. The policy was strictly enforced during the Hongwu era.[79]

Zhu Yuanzhang passed a law on mandatory hairstyle on 24 September 1392, mandating that all males grow their hair long and making it illegal for them to shave part of their foreheads while leaving strands of hair which was the Mongol hairstyle. The penalty for both the barber and the person who was shaved and his sons was castration if they cut their hair and their families were to be sent to the borders for exile. This helped eradicated partially shaved Mongol hairstyles and enforced long Han hairstyle.[80]

Military

[edit]

The Hongwu Emperor realized that the Northern Yuan still posed a threat to the Ming, even though they had been driven away after the collapse of the Yuan. He decided to reassess the orthodox Confucian view that the military class was inferior to that of the scholar bureaucracy. He kept a powerful army, which in 1384 he reorganized using a model known as the weisuo system (simplified Chinese: 卫所制; traditional Chinese: 衞所制; lit. 'guard battalion'). Each military unit consisted of 5,600 men divided into five battalions and ten companies.[81] By 1393 the total number of weisuo troops had reached 1,200,000. Soldiers were also assigned land on which to grow crops whilst their positions were made hereditary. This type of system can be traced back to the fubing system (Chinese: 府兵制) of the Sui and Tang dynasties.

Training was conducted within local military districts. In times of war, troops were mobilized from all over the empire on the orders of the Ministry of War, and commanders were appointed to lead them to battle. After the war, the army was disbanded into smaller groups and sent back to their respective districts, while the commanders had to return their authority to the state. This system helped to prevent military leaders from having too much power. The military was under the control of a civilian official for large campaigns, instead of a military general.[citation needed]

Bureaucratic reforms and consolidation of power

[edit]Hongwu attempted, and largely succeeded in, the consolidation of control over all aspects of government, so that no other group could gain enough power to overthrow him. He also buttressed the country's defense against the Mongols. He increasingly concentrated power in his own hands. He abolished the chancellor's post, which had been head of the main central administrative body under past dynasties, by suppressing a plot for which he had blamed his chancellor Hu Weiyong. Many argue that Hongwu, because of his wish to concentrate absolute authority in his own hands, removed the only insurance against incompetent emperors.[citation needed]

However, Hongwu could not govern the sprawling Ming Empire all by himself and had to create the new institution of the "Grand Secretary". This cabinet-like organisation progressively took on the powers of the abolished prime minister, becoming just as powerful in time. Ray Huang argued that Grand-Secretaries, outwardly powerless, could exercise considerable positive influence from behind the throne.[citation needed] Because of their prestige and the public trust which they enjoyed, they could act as intermediaries between the emperor and the ministerial officials, and thus provide a stabilising force in the court.

In Hongwu's elimination of the traditional offices of grand councilor, the primary impetus was Hu Weiyong's alleged attempt to usurp the throne. Hu was the Senior Grand Councilor and a capable administrator; however over the years, the magnitude of his powers, as well as involvement in several political scandals eroded the paranoid emperor's trust in him. Finally, in 1380, Hongwu had Hu and his entire family arrested and executed on charges of treason. Using this as an opportunity to purge his government, the emperor also ordered the execution of countless other officials, as well as their families, for associating with Hu. The purge lasted over a decade and resulted in more than 30,000 executions. In 1390, even Li Shanchang, one of the closest old friends of the emperor, who was rewarded as the biggest contributor to the founding of the Ming Empire, was executed along with over 70 members of his extended family. A year after his death, a deputy in the Board of Works made a submission to the emperor appealing Li's innocence, arguing that since Li was already at the apex of honour, wealth and power, the accusation that he wanted to help someone else usurp the throne was clearly ridiculous. Hongwu was unable to refute the accusations and finally ended the purge shortly afterwards.

Hongwu also noted the destructive role of court eunuchs under the previous dynasties. He drastically reduced their numbers, forbidding them to handle documents, insisting that they remain illiterate, and executing those who commented on state affairs. The emperor had a strong aversion to the eunuchs, epitomized by a tablet in his palace stipulating: "Eunuchs must have nothing to do with the administration". This aversion to eunuchs did not long continue among his successors, as the Hongwu and Jianwen emperors' harsh treatment of eunuchs allowed the Yongle Emperor to employ them as a power base during his coup.[11] In addition to Hongwu's aversion to eunuchs, he never consented to any of his consort kin becoming court officials. This policy was fairly well-maintained by later emperors, and no serious trouble was caused by the empresses or their families.

The Embroidered Uniform Guard was transformed into a secret police organization during the Hongwu era. It was given the authority to overrule judicial proceedings in prosecutions with full autonomy in arresting, interrogating and punishing anyone, including nobles and the emperor's relatives. In 1393, Jiang Huan (蔣瓛), the chief of the Guard, accused general Lan Yu of plotting rebellion. 15,000 people were executed in familial extermination during the subsequent purges, according to Hongwu.[82]

Through the repeated purges and the elimination of the historical posts, Hongwu fundamentally altered the centuries-old government structure of China, greatly increasing the emperor's absolutism.

Legal reforms

[edit]

The legal code drawn up in the time of Hongwu was considered one of the great achievements of the era. The History of Ming mentioned that as early as 1364, the monarchy had started to draft a code of laws. This code was known as Da Ming Lü (大明律, "Code of the Great Ming"). The emperor devoted much time to the project and instructed his ministers that the code should be comprehensive and intelligible, so as not to allow any official to exploit loopholes in the code by deliberately misinterpreting it. The Ming code laid much emphasis on family relations. The code was a great improvement on the code of the Tang dynasty in regards to the treatment of slaves. Under the Tang code, slaves were treated as a species of domestic animal; if they were killed by a free citizen, the law imposed no sanction on the killer. Under the Ming dynasty, the law protected both slaves and free citizens.[citation needed]

Later during his reign, however, the Code of the Great Ming was set aside in favor of the far harsher legal system documented in Da Gao (大誥, "Great Announcements"). Compared to the Da Ming Lü, the penalties for almost all crimes were drastically increased, with more than 1,000 crimes eligible for capital punishment.[83][84] Much of the Da Gao was dedicated to the government and officials, particularly for anti-corruption. Officials who embezzled more than the equivalent of 60 liang of silver (one liang was around 30 grams) were to be beheaded and then flayed, the skin publicly exhibited. Zhu Yuanzhang granted all people the right to capture officials suspected of crimes and directly send them to the capital, a first in Chinese history.[83] Apart from regulating the government, Da Gao aimed to set limits to various social groups. For example, "idle men" who did not change their lifestyles after the new law came into effect would be executed and their neighbors exiled. Da Gao also included extensive sumptuary laws, down to details such as banning ornaments in heating rooms in the houses of commoners.[84]

Economic policy

[edit]Supported by the scholar-bureaucrats, he accepted the Confucian viewpoint that merchants were solely parasitic. He felt that agriculture should be the country's source of wealth and that trade was ignoble. As a result, the Ming economic system emphasized agriculture, unlike the economic system of the Song dynasty which had preceded the Yuan, and relied on traders and merchants for revenues. Hongwu also supported the creation of self-supporting agricultural communities.

However, his prejudice against merchants did not diminish the numbers of traders. On the contrary, commerce increased significantly during the Hongwu era because of the growth of industry throughout the empire. This growth in trade was due in part to poor soil conditions and the overpopulation of certain areas, which forced many people to leave their homes and seek their fortunes in trade. A book titled Tu Pien Hsin Shu,[citation needed] written during the Ming gave a detailed description of the activities of merchants at that time.

Although the Hongwu era saw the reintroduction of paper currency, its development was stifled from the beginning. Not understanding inflation, Hongwu gave out so much paper money as rewards that by 1425, the state was forced to restore copper coins because the paper currency had sunk to only 1/70 of its original value.

Education policy

[edit]Hongwu tried to remove Mencius from the Temple of Confucius as certain parts of his work were deemed harmful. These include "the people are the most important element in a nation; the spirits of the land and grain are the next; the sovereign is the lightest" (Mengzi, Jin Xin II), as well as, "when the prince regards the ministers as the ground or as grass, they regard him as a robber and an enemy" (Mengzi, Li Lou II). The effort failed due to the objection from important officials, particularly Qian Tang (錢唐), Minister of Justice.[85] Eventually, the emperor organized the compilation of the Mencius Abridged (孟子節文) in which 85 lines were deleted. Apart from those mentioned above, the omitted sentences also included those describing rules of governance, promoting benevolence, and those critical of King Zhou of Shang.[86]

At the Guozijian, law, math, calligraphy, equestrianism, and archery were emphasized by Hongwu in addition to Confucian classics and also required in the imperial examinations.[87][88][89][90][91] Archery and equestrianism were added to the exam by Hongwu in 1370, similarly to how archery and equestrianism were required for non-military officials at the College of War (武舉) in 1162 by Emperor Xiaozong of Song.[92] The area around the Meridian Gate of Nanjing was used for archery by guards and generals under Hongwu.[93] A cavalry based army modeled on the Yuan military was implemented by the Hongwu and Yongle Emperors.[94] Hongwu's army and officialdom incorporated Mongols.[95]

Equestrianism and archery were favorite pastimes of He Suonan who served in the Yuan and Ming militaries under Hongwu.[96] Archery towers were built by Zhengtong Emperor at the Forbidden City and archery towers were built on the city walls of Xi'an which had been erected by Hongwu.[97][98]

Hongwu wrote essays which were posted in every village throughout China warning the people to behave or else face horrifying consequences.[73] The 1380s writings of Hongwu includes the "Great warnings" or "Grand Pronouncements",[99] and the "Ancestral Injunctions".[100][101] He wrote the Six Maxims (六諭,[102] 聖諭六言[103][104][105][106][107]) which inspired the Sacred Edict of the Kangxi Emperor.[108][109][110]

Around 1384, Hongwu ordered the Chinese translation and compilation of Islamic astronomical tables, a task that was carried out by the scholars Mashayihei, a Muslim astronomer, and Wu Bozong, a Chinese scholar-official. These tables came to be known as the Huihui Lifa, which was published in China a number of times until the early 18th century,[111]

Religious and ethnic policies

[edit]

Mongol and Central Asian Semu women and men (with the explicit exclusion of all Hui Hui people and Kipchaks due to their different racial features) were required by the Code of the Great Ming to marry Han Chinese, with the voluntary consent of both spouses and families after the first Ming emperor Hongwu passed the law in Article 122, with the Mongols and Semu forbidden from marrying their own kind.[112][113][114]

The Hongwu Emperor married off his own son Zhu Shuang to the Mongol consort Minlie of the Wang clan (愍烈妃 王氏; d. 1395), the primary consort, younger sister of Köke Temür. David M. Robinson indicated it is unknown whether the Ming marriage laws were actually enforced. At the same time, the Hongwu Emperor also wanted to segregate barbarians like the Mongol and Semu and force them not to use Han names so they could maintain their distinctiveness and not assimilate or get mistaken for Han.[115][116][117][118]

Ming Chinese officials above all regarded Mongols under their rule as a separate ethnicity registered in official hereditary Mongol households, regardless of their lifestyle, dress or language, making it irrelevant whether their culture survived, the Ming viewed everyone who was registered in an official Mongol household (most of which were classified as part of Ming military households) as a Mongol legally.[119]

Hongwu ordered the construction of several mosques in Nanjing, Yunnan, Guangdong and Fujian,[120][13] and had inscriptions praising Muhammad placed in them. He rebuilt the Jinjue Mosque in Nanjing and large numbers of Hui people moved to the city during his rule.[121]

Foreign policy

[edit]

Hongwu designated the "country without conquest" (不征之国). He listed 15 countries that Ming would not attempt to conquest, such as Japan, Srivijaya, Thailand, Liuqiu and the Vietnamese Trần dynasty.[122]

Vietnam

[edit]Hongwu was a non-interventionist, refusing to intervene in a Vietnamese invasion of Champa to help the Chams, only rebuking the Vietnamese for their invasion, being opposed to military action abroad.[123] He specifically warned future emperors only to defend against foreign barbarians, and not engage in expansionist military campaigns for glory and conquest.[124] In his 1395 ancestral injunctions, the emperor specifically wrote that China should not attack Champa, Cambodia or Annam (Vietnam).[125][126] With the exception of his turn against aggressive expansion, much of Hongwu's foreign policy and his diplomatic institutions were based on Yuan practice.[127]

Japanese pirates

[edit]Hongwu sent a message to the Ashikaga shogunate that his army would "capture and exterminate your bandits, head straight for your country, and put your king in bonds".[128] In fact, many of the "dwarf pirates" and "eastern barbarians" raiding his coasts were Chinese,[129][130] and Hongwu's response was almost entirely passive. The shogun replied "Your great empire may be able to invade Japan, but our small state is not short of a strategy to defend ourselves."[131] The necessity of protecting his state against the Northern Yuan remnants[132] meant that the most Hongwu was able to accomplish against Japan was a series of "sea ban" measures. Private foreign trade was made punishable by death, with the trader's family and neighbors exiled;[133] ships, docks, and shipyards were destroyed, and ports were sabotaged.[134][131] The plan was at odds with Chinese tradition and was counterproductive as it tied up resources. 74 coastal garrisons had to be established from Guangzhou to Shandong, though they were often manned by local gangs.[134] Hongwu's measures limited tax receipts, impoverished and provoked both coastal Chinese and Japanese against the Hongwu regime,[131] and actually resulted in an increase in piracy,[130] offering too little as a reward for good behavior and enticement for Japanese authorities to root out their own smugglers and pirates.[131] Regardless of the policy, piracy had dropped to negligible levels by the time of its abolition in 1568.[130]

Nonetheless, the sea ban was added by Hongwu to his Ancestral Injunctions[134] and so continued to be broadly enforced through most of the rest of his dynasty: for the next two centuries, the rich farmland of the south and the military theaters of the north were linked only by the Jinghang Canal.[135]

Despite the deep distrust, in Hongwu's Ancestral Injunctions, he listed Japan along with 14 other countries as "countries against which campaigns shall not be launched", and advised his descendants to maintain peace with them. This policy was violated by his son, the Yongle Emperor, who ordered multiple interventions in northern Vietnam, but remained influential for several centuries afterwards.[136]

Byzantine Empire

[edit]The History of Ming compiled during the early Qing dynasty describes how Hongwu met with an alleged merchant of the Byzantine Empire named "Nieh-ku-lun" (捏古倫). In September 1371, he had the man sent back to his native country with a letter announcing the founding of the Ming dynasty to John V Palaiologos.[137][138][139] It is speculated that the merchant was actually a former bishop of Beijing called Nicolaus de Bentra, sent by Pope John XXII to replace Archbishop John of Montecorvino in 1333.[137][140] The History of Ming goes on to explain that contacts between China and Fu lin ceased after this point, and diplomats of the great western sea (the Mediterranean Sea) did not appear in China again until the 16th century, with the Italian Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci.[137]

Death

[edit]

After a 30-year reign, Hongwu died on 24 June 1398, at the age of 69. After his death, his physicians were penalized. He was buried at Xiaoling Mausoleum on the Purple Mountain, in the east of Nanjing. The mass sacrifice of concubines after the emperor's death, a practice long disappeared among Chinese dynasties, was revived by Zhu Yuanzhang, probably to clear potential obstacles to the reign of his chosen successor. At least 38 concubines were killed as part of Hongwu's funeral human sacrifice.[141][142]

Assessment

[edit]Historians consider Hongwu as one of the most significant emperors of China. As Patricia Buckley Ebrey puts it, "Seldom has the course of Chinese history been influenced by a single personality as much as it was by the founder of the Ming dynasty, Zhu Yuanzhang."[143] His rise to power was fast despite his having a poor and humble origin. In 11 years, he went from being a penniless monk to the most powerful warlord in China. Five years later, he became emperor of China. Simon Leys described him this way:

'an adventurer from peasant stock, poorly educated, a man of action, a bold and shrewd tactician, a visionary mind, in many respects a creative genius; naturally coarse, cynical, and ruthless, he eventually showed symptoms of paranoia, bordering on psychopathy.'[144]

Family

[edit]Zhu Yuanzhang had many Korean and Mongolian women among his concubines along with his Empress Ma and had 16 daughters and 26 sons with all of them.[145]

Consorts and issue

[edit]The History of Ming lists the consorts and issue of the Hongwu Emperor in its princes' and princesses' biographies.

- Empress Xiaocigao, of the Ma clan

- Zhu Biao, Crown Prince Yiwen (10 October 1355 – 17 May 1392), first son

- Zhu Shuang, Prince Min of Qin (3 December 1356 – 9 April 1395), second son

- Zhu Gang, Prince Gong of Jin (18 December 1358 – 30 March 1398), third son

- Zhu Di, Prince of Yan, later the Yongle Emperor (2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424), fourth son

- Zhu Su, Prince Ding of Zhou (8 October 1361 – 2 September 1425), fifth son

- Princess Ningguo (寧國公主; 1364 – 7 September 1434), second daughter

- Married Mei Yin, Duke Rong (梅殷; d. 1405) in 1378, and had issue (two sons)

- Princess Anqing (安慶公主), fourth daughter

- Married Ouyang Lun (歐陽倫; d. 23 July 1397) on 23 December 1381

- Noble Consort Chengmu, of the Sun clan (1343–1374)

- Princess Lin'an (臨安公主; 1360 – 17 August 1421), personal name Yufeng (玉鳳), first daughter

- Married Li Qi (李祺; d. 1402), a son of Li Shanchang, in 1376, and had issue (two sons)

- Princess Huaiqing (懷慶公主; 1366 – 15 July 1425), sixth daughter

- Married Wang Ning, Marquis Yongchun (王寧) on 11 September 1382, and had issue (two sons)

- Tenth daughter

- Thirteenth daughter

- Princess Lin'an (臨安公主; 1360 – 17 August 1421), personal name Yufeng (玉鳳), first daughter

- Noble Consort, of the Jiang clan (貴妃 江氏)

- Noble Consort, of the Zhao clan (貴妃 趙氏)

- Zhu Mo, Prince Jian of Shen (1 September 1380 – 11 June 1431), 21st son

- Consort Ning, of the Guo clan

- Princess Runing (汝寧公主), fifth daughter

- Married Lu Xian (陸賢) on 11 June 1382

- Princess Daming (大名公主; 1368 – 30 March 1426), seventh daughter

- Married Li Jian (李堅; d. 1401) on 2 September 1382, and had issue (one son)

- Zhu Tan, Prince Huang of Lu (15 March 1370 – 2 January 1390), tenth son

- Princess Runing (汝寧公主), fifth daughter

- Consort Zhaojingchong, of the Hu clan (昭敬充妃 胡氏)

- Zhu Zhen, Prince Zhao of Chu (5 April 1364 – 22 March 1424), sixth son

- Consort Ding, of the Da clan (定妃 達氏; d. 1390)

- Zhu Fu, Prince Gong of Qi (23 December 1364 – 1428), seventh son

- Zhu Zi, Prince of Tan (潭王 朱梓; 6 October 1369 – 18 April 1390), eighth son

- Consort An, of the Zheng clan (安妃 鄭氏)

- Princess Fuqing (福清公主; 1370 – 28 February 1417), eighth daughter

- Married Zhang Lin (張麟) on 26 April 1385, and had issue (one son)

- Princess Fuqing (福清公主; 1370 – 28 February 1417), eighth daughter

- Consort Hui, of the Guo clan

- Zhu Chun, Prince Xian of Shu (蜀獻王 朱椿; 4 April 1371 – 22 March 1423), 11th son

- Zhu Gui, Prince Jian of Dai (25 August 1374 – 29 December 1446), 13th son

- Princess Zhenyi of Yongjia (永嘉貞懿公主; 1376 – 12 October 1455), 12th daughter

- Married Guo Zhen (郭鎮; 1372–1399) on 23 November 1389, and had issue (one son)

- Zhu Hui, Prince of Gu (谷王 朱橞; 30 April 1379 – 1428), 19th son

- Princess Ruyang (汝陽公主), 15th daughter

- Married Xie Da (謝達; d. 1404) on 23 August 1394

- Consort Shun, of the Hu clan (順妃 胡氏)

- Zhu Bai, Prince Xian of Xiang (湘獻王 朱柏; 12 September 1371 – 18 May 1399), 12th son

- Consort Xian, of the Li clan (賢妃 李氏)

- Zhu Jing, Prince Ding of Tang (唐定王 朱桱; 11 October 1386 – 8 September 1415), 23rd son

- Consort Hui, of the Liu clan (惠妃 劉氏)

- Zhu Dong, Prince Jing of Ying (郢靖王 朱棟; 21 June 1388 – 14 November 1414), 24th son

- Consort Li, of the Ge clan (麗妃 葛氏)

- Zhu Yi, Prince Li of Yi (伊厲王 朱㰘; 9 July 1388 – 8 October 1414), 25th son

- Prince Zhu Nan (朱楠; 4 January 1394 – February 1394), 26th son

- Consort Zhuangjinganronghui, of the Cui clan (莊靖安榮惠妃 崔氏)

- Consort, of the Han clan (妃 韓氏)

- Zhu Zhi, Prince Jian of Liao (24 March 1377 – 4 June 1424), 15th son

- Princess Hanshan (含山公主; 1381 – 18 October 1462), 14th daughter

- Married Yin Qing (尹清) on 11 September 1394, and had issue (two sons)

- Consort, of the Yu clan (妃 余氏)

- Zhu Zhan, Prince Jing of Qing (慶靖王 朱㮵; 6 February 1378 – 23 August 1438), 16th son

- Consort, of the Yang clan (妃 楊氏)

- Zhu Quan, Prince Xian of Ning (27 May 1378 – 12 October 1448), 17th son

- Consort, of the Zhou clan (妃 周氏)

- Zhu Pian, Prince Zhuang of Min (岷莊王 朱楩; 9 April 1379 – 10 May 1450), 18th son

- Zhu Song, Prince Xian of Han (韓憲王 朱松; 20 June 1380 – 19 November 1407), 20th son

- Beauty, of the Zhang clan (美人 張氏), personal name Xuanmiao (玄妙)

- Princess Baoqing (寶慶公主; 1394–1433), 16th daughter

- Married Zhao Hui (趙輝; 1387–1476) in 1413

- Princess Baoqing (寶慶公主; 1394–1433), 16th daughter

- Lady, of the Lin clan (林氏)

- Princess Nankang (南康公主; 1373 – 15 November 1438), personal name Yuhua (玉華), 11th daughter

- Married Hu Guan (胡觀; d. 1403) in 1387, and had issue (one son)

- Princess Nankang (南康公主; 1373 – 15 November 1438), personal name Yuhua (玉華), 11th daughter

- Lady, of the Gao clan (郜氏)

- Zhu Ying, Prince Zhuang of Su (肅莊王 朱楧; 10 October 1376 – 5 January 1420), 14th son

- Unknown

- Princess Chongning (崇寧公主), third daughter

- Married Niu Cheng (牛城) on 21 December 1384

- Zhu Qi, Prince of Zhao (趙王 朱杞; October 1369 – 16 January 1371), ninth son

- Princess Shouchun (壽春公主; 1370 – 1 August 1388), ninth daughter

- Married Fu Zhong (傅忠; d. 20 December 1394), the first son of Fu Youde, on 9 April 1386, and had issue (one son)

- Zhu Ying, Prince Hui of An (安惠王 朱楹; 18 October 1383 – 9 October 1417), 22nd son

- Princess Chongning (崇寧公主), third daughter

Ancestry

[edit]| Zhu Sijiu | |||||||||||||||

| Zhu Chuyi | |||||||||||||||

| Empress Heng | |||||||||||||||

| Zhu Shizhen (1281–1344) | |||||||||||||||

| Empress Yu | |||||||||||||||

| Hongwu Emperor (1328–1398) | |||||||||||||||

| Lord Chen (1235–1334) | |||||||||||||||

| Empress Chun (1286–1344) | |||||||||||||||

In popular culture

[edit]Novels

[edit]- The Heaven Sword and Dragon Saber (倚天屠龍記), a 1961–63 wuxia novel by Louis Cha. Zhu Yuanzhang appears as a minor character in the novel. Zhu Yuanzhang has been portrayed by various actors in the films and television series adapted from this novel.

- She Who Became the Sun, a 2021 novel by Shelley Parker-Chan. Zhu Yuanzhang and his rise to power is the historical basis of the main character Zhu Chongba.

- He Who Drowned the World, the 2023 sequel by Shelley Parker-Chan. Zhu Yuanzhang declares himself emperor and forms the Ming dynasty at the end of the novel.

- Iron Widow, a 2021 novel by Xiran Jay Zhao. Along with Ma Xiuying, Zhu Yuanzhang appears as a minor character in the novel.

Television

[edit]- Born to be a King (大明群英), a 1987 Hong Kong television series produced by TVB and starring Simon Yam as Zhu Yuanzhang.

- Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋), a 1993 Chinese television series produced by Beijing TV and starring Lü Qi as Zhu Yuanzhang.

- Empress Ma With Great Feet (大腳馬皇后), a 2002 Chinese television series about Zhu Yuanzhang's wife, Empress Ma. Tang Guoqiang starred as Zhu Yuanzhang.

- Chuanqi Huangdi Zhu Yuanzhang (傳奇皇帝朱元璋), a 2006 Chinese television series starring Chen Baoguo as Zhu Yuanzhang.

- Founding Emperor of Ming Dynasty (朱元璋), a 2006 Chinese television series directed by Feng Xiaoning and starring Hu Jun as Zhu Yuanzhang.

- The Legendary Liu Bowen (神機妙算劉伯溫), a 2006–2008 Taiwanese television series about Zhu Yuanzhang's adviser, Liu Bowen. It was produced by TTV and starred Huo Zhengqi as Zhu Yuanzhang.

- Zhenming Tianzi (真命天子), a 2015 Chinese television series produced by Jian Yuanxin and starring Zhang Zhuowen as Zhu Yuanzhang.

- Love Through Different Times (穿越时空的爱恋), a 2002 Chinese television comedy-drama that is considered the first time-travel television series produced in mainland China.

See also

[edit]- Chinese emperors family tree (late)

- Huang Ming Zu Xun, the "Ancestral Instructions" written by Hongwu to guide his descendants

- Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum

- Ming–Tibet relations

- Ming dynasty in Inner Asia

- Hongwu Tongbao

Notes

[edit]- ^ Zhu Yuanzhang had already been in control of Nanjing since 1356, and was conferred the title of "Duke of Wu" (吳國公) by the rebel leader Han Lin'er (韓林兒) in 1361. He started autonomous rule as the self-proclaimed "Prince of Wu" on 4 February 1364. He was proclaimed emperor on 23 January 1368 and established the Ming dynasty on that same day.

- ^ a b 21 October 1328 is the Julian calendar equivalent of the 18th day of the 9th month of the Tianli (天曆) regnal period of the Yuan dynasty. When calculated using the Proleptic Gregorian calendar, the date is 29 October.[5][6]: 11 [7]

- ^ Upon his successful usurpation in 1402, the Yongle Emperor voided the era of the Jianwen Emperor and continued the Hongwu era until the beginning of Chinese New Year in 1403, when the new Yongle era came into effect. This dating continued for a few of his successors until the Jianwen era was reestablished in the late 16th century.

- ^ Conferred by the Jianwen Emperor

- ^ Conferred by the Yongle Emperor

- ^ Changed by the Jiajing Emperor

References

[edit]- ^ a b Goodrich, Luther Carrington; Fang Chaoying, eds. (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368–1644. Vol. 1. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 258–259. ISBN 978-0-231-03801-0.

- ^ Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (2001). Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle (illustrated ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 28. ISBN 0295981091.

- ^ Becker, Jasper (1998). Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine (illustrated, reprint ed.). Macmillan. p. 131. ISBN 0805056688.

- ^ Becker, Jasper (2007). Dragon Rising: An Inside Look at China Today. National Geographic Books. p. 167. ISBN 978-1426202100.

- ^ Teng Ssu-yü (1976). "Chu Yüan-chang". In Goodrich, Luther Carrington; Fang Chaoying (eds.). Dictionary of Ming biography, 1368–1644. Vol. I: A–L. Association for Asian Studies and Columbia University Press. pp. 381–392. ISBN 0231038011. OL 10195404M.

- ^ Mote, Frederick W. (1988). "The Rise of the Ming Dynasty, 1330–1367". In Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–57. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521243322.003. ISBN 978-1-139-05475-1.

- ^ "Hung-wu | emperor of Ming dynasty". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Zhu Yuanzhang – Founder Emperor of Ming Dynasty | ChinaFetching". Chinese Culture. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Dardess, John W. (1972). Parsons, James Bunyan; Simonovskaia, Larisa Vasil'evna; Wen-Chih, Li (eds.). "The Late Ming Rebellions: Peasants and Problems of Interpretation". The Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 3 (1): 103–117. doi:10.2307/202464. hdl:1808/13251. ISSN 0022-1953. JSTOR 202464.

- ^ "An introduction to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) (article)". Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ a b Chan Hok-lam. "Legitimating Usurpation: Historical Revisions under the Ming Yongle Emperor (r. 1402–1424) Archived 15 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine". The Legitimation of New Orders: Case Studies in World History. Chinese University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-9629962395. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ The Legitimation of New Orders: Case Studies in World History. Chinese University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-9629962395. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ a b c Hagras, Hamada (2019). "The Ming Court as Patron of the Chinese Islamic Architecture: The Case Study of the Daxuexi Mosque in Xi'an" (PDF). Shedet. 6 (6): 134–158. doi:10.36816/SHEDET.006.08.

- ^ Pines, Yuri; Shelach, Gideon; Falkenhausen, Lothar von; Yates, Robin D. S. (2013). Birth of an Empire. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-28974-1.

- ^ Fang, Qiang; Oklahoma, Xiaobing Li, University of Central (2018). Corruption and Anticorruption in Modern China. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4985-7432-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis, eds. (1988). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-1139054751.

- ^ a b 劉辰. 國初事迹

- ^ a b 李默. 孤樹裒談

- ^ a b 楊一凡(1988). 明大誥研究. Jiangsu Renmin Press.

- ^ a b 鞍山老人万里寻祖20年探出"小云南". News.eastday.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ a b 元末明初的士人活動 – 歷史學科中心. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ Farmer, Edward L. (1995). Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation. Brill. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-90-04-10391-7.

- ^ Farmer (1995), p. 36

- ^ Zhang Wenxian. "The Yellow Register Archives of Imperial Ming China Archived 26 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine". Libraries & the Cultural Record, Vol. 43, No. 2 (2008), pp. 148–175. Univ. of Texas Press. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ Mote, Frederick W. (1988). The Cambridge History of China Volume 7 The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 11.

- ^ Dreyer, 22–23.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 1

- ^ Lu, Hanchao (2005). Street Criers: A Cultural History of Chinese Beggars. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5148-3.

- ^ Mote, Frederick W. (2003). Imperial China 900–1800 (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 544. ISBN 0674012127.

- ^ Mote, J.F. Imperial China 900–1800 Harvard University Press (5 December 2003) ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7 pp.543–545 Google Books Search

- ^ {Yonglin, Jiang (tr). The Great Ming Code: Da Ming lü. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2005, pp xxxiv}

- ^ {Mote, Frederick W. and Twitchett, Denis (ed), The Cambridge History of China, Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: The Cambridge University Press, 1988, pp 45.}

- ^ "Emperor Hongwu Biography". World History. 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ Bowman, John Stewart, ed. (2000). Columbia chronologies of Asian history and culture. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 39. ISBN 978-0231500043. OCLC 51542679.

- ^ Hannah, Ian C. (1900). A brief history of Eastern Asia. TF Unwin. p. 83. ISBN 9781236379818.

- ^ Ebrey, "Cambridge Illustrated History of China", pg. 191

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2014). 500 great military leaders. Tucker, Spencer, 1937–. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 852. ISBN 9781598847581. OCLC 964677310.

- ^ Farmer, Edward L., ed. (1995). Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. BRILL. pp. 21, 23. ISBN 9004103910. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Ming Hung, Hing (2016). From the Mongols to the Ming Dynasty : How a Begging Monk Became Emperor of China, Zhu Yuan Zhang. New York: Algora Publishing. pp. 60–61. ISBN 9781628941524. OCLC 952155600.

- ^ Lindesay, William (2015). The Great Wall in 50 Objects. Penguin Books China. ISBN 9780734310484.

- ^ Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, pp. 59–63, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- ^ Edward L. Farmer, Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. BRILL, 1995. ISBN 90-04-10391-0, ISBN 978-90-04-10391-7. On Google Books. P 23.

- ^ Linda Cooke Johnson, Cities of Jiangnan in Late Imperial China. SUNY Press, 1993. ISBN 0-7914-1423-X, 9780791414231 On Google Books Archived 8 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis; Fairbank, John K., eds. (1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Contributors Denis Twitchett, John K. Fairbank (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 108–111. ISBN 978-0521243322. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis; Fairbank, John K., eds. (1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Contributors Denis Twitchett, John K. Fairbank (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0521243322. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ Contributor Australian National University. Dept. of Far Eastern History (1988). Papers on Far Eastern History, Volumes 37–38. Department of Far Eastern History, Australian National University. p. 17. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (2001). Perpetual happiness: the Ming emperor Yongle. University of Washington Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0295800226. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 125–127. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 144–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- ^ Thomas H.C. Lee, Education in Traditional China: A History. Leiden: Brill, 2000,156.

- ^ "Taizu shilu, vol. 30". Ming Shilu.

不得服两截胡衣,其辫发锥髻。胡服胡语胡姓一切禁止。斟酌损益,皆断自圣心。

- ^ Stearns, Peter N., et al. World Civilizations: The Global Experience. AP Edition DBQ Update. New York: Pearson Education, Inc., 2006. 508.

- ^ Schneewind, Sarah, Community Schools and the State in Ming China. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006, 12–3.

- ^ Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 122–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- ^ 有趣的南京地名. People's Daily. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ 长乐街:秦淮影照古廊房. longhoo.net. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ 馬生龍. 鳳凰台紀事

- ^ History of Ming, vol.139

- ^ Wu Han, 胡惟庸黨案考

- ^ Qian Qianyi, 初學集, vol.104

- ^ Xu Zhenqing (徐禎卿). 剪勝野聞

- ^ Confessions of the Lan Yu clique (藍玉黨供狀)

- ^ FREDERIC WAKEMAN JR. (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 343–344. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- ^ "Between Winds and Clouds: Chapter 3". gutenberg-e.org. Archived from the original on 17 February 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ "Between Winds and Clouds: Chapter 4". gutenberg-e.org. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ "Between Winds and Clouds: Chapter 5". gutenberg-e.org. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ "Gold Treasures Discovered in Ming Dynasty Tomb (Photos)". Live Science. 13 May 2015. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ "Ming Dynasty Tomb Tells A Remarkable Life's Story". 14 May 2015. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 133–134. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ Stearns, Peter N., et al. World Civilizations: The Global Experience. AP Edition DBQ Update. New York: Pearson Education, Inc., 2006. 511.

- ^ ȼ䡢Ⱥʷ. literature.org.cn. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016.

- ^ 山西社科网. sxskw.org.cn. 19 February 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ a b Marshall Cavendish Corporation; Steven Maddocks; Dale Anderson; Jane Bingham; Peter Chrisp; Christopher Gavett (2006). Exploring the Middle Ages. Marshall Cavendish. p. 519. ISBN 978-0-7614-7613-9. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Farmer, Edward L. (1995). "Appendix. The placard of people's instructions" (PDF). Zhu Yuanzhang and early Ming legislation. Brill. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ 衔微 (1963). "明代的里甲制度". 历史教学 (4). Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ 吴钩 (2013). "戶口册上的中国". 国家人文历史 (3). Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ 王毓铨 (1959). "明代的军户". 历史研究 (8). Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ 高寿仙 (2013). "关于明朝的籍贯与户籍问题". 北京联合大学学报 (1). Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ 陈宝良 (2014). "明代户籍是如何管控的". 人民论坛 (17). Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ CHAN, HOK-LAM (2009). "Ming Taizu's 'Placards' on Harsh Regulations and Punishments Revealed in Gu Qiyuan's 'Kezuo Zhuiyu.'". Asia Major. 22 (1): 28. JSTOR 41649963. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ (In Chinese) She Yiyuan (佘一元), Shanhaiguan Chronicle (山海关志)

- ^ History of Ming, vol.132.

- ^ a b 杨一凡 (1981). "明《大浩》初探". 《北京政法学院学报》 (1). Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ a b Diao, Shenghu; Zou, Mengyuan (2018). "Heavy punishment for crimes in Zhu Yuanzhang period reflected in Da Gao". Journal of Guangzhou University (Social Science Edition). 17 (3): 13–17.

- ^ Monumenta Serica. H. Vetch. 2007. p. 167.

- ^ Zhang, Hongjie. "朱元璋为什么要删《孟子》?". People's Daily Online. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 122–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- ^ Stephen Selby (1 January 2000). Chinese Archery. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 267–. ISBN 978-962-209-501-4.

- ^ Edward L. Farmer (1995). Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. BRILL. pp. 59–. ISBN 978-90-04-10391-7.

- ^ Sarah Schneewind (2006). Community Schools and the State in Ming China. Stanford University Press. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-0-8047-5174-2.

- ^ "Ming Empire 1368-1644 by Sanderson Beck". san.beck.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ Lo Jung-pang (1 January 2012). China as a Sea Power, 1127–1368: A Preliminary Survey of the Maritime Expansion and Naval Exploits of the Chinese People During the Southern Song and Yuan Periods. NUS Press. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-9971-69-505-7. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ "Hongwu Reign-The Palace Museum". en.dpm.org.cn. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ Michael E. Haskew; Christer Joregensen (9 December 2008). Fighting Techniques of the Oriental World: Equipment, Combat Skills, and Tactics. St. Martin's Press. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-0-312-38696-2.

- ^ Dorothy Perkins (19 November 2013). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Routledge. pp. 216–. ISBN 978-1-135-93562-7.

- ^ Gray Tuttle; Kurtis R. Schaeffer (12 March 2013). The Tibetan History Reader. Columbia University Press. pp. 303–. ISBN 978-0-231-51354-8.

- ^ "Xi'an City Wall 西安城墙". hua.umf.maine.edu. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Forbidden City Palace Museum 故宫博物院 Beijing". hua.umf.maine.edu. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ John Makeham (2008). China: The World's Oldest Living Civilization Revealed. Thames & Hudson. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-500-25142-3.

- ^ Frederick W. Mote; Denis Twitchett (26 February 1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644. Cambridge University Press. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- ^ "pp. 45, 47, 51" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Elisabeth Kaske (2008). The Politics of Language in Chinese Education: 1895 – 1919. BRILL. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-90-04-16367-6.

- ^ Benjamin A. Elman (1 November 2013). Civil Examinations and Meritocracy in Late Imperial China. Harvard University Press. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-0-674-72604-8. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Kerry J. Kennedy; Gregory Fairbrother; Zhenzhou Zhao (15 October 2013). Citizenship Education in China: Preparing Citizens for the "Chinese Century". Routledge. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-1-136-02208-1. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Michael Lackner, Ph.D.; Natascha Vittinghoff (January 2004). Mapping Meanings: The Field of New Learning in Late Qing China; [International Conference "Translating Western Knowledge Into Late Imperial China", 1999, Göttingen University]. BRILL. pp. 269–. ISBN 978-90-04-13919-0.

- ^ Zhengyuan Fu (1996). China's Legalists: The Earliest Totalitarians and Their Art of Ruling. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-1-56324-779-8.

- ^ Benjamin A. Elman; John B. Duncan; Herman Ooms (2002). Rethinking confucianism: past and present in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. University of California Los Angeles. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-883191-07-8.

- ^ William Theodore De Bary (1998). Asian Values and Human Rights: A Confucian Communitarian Perspective. Harvard University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-674-04955-0.

- ^ William Theodore De Bary; Wing-tsit Chan (1999). Sources of Chinese Tradition. Columbia University Press. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-231-11270-3.

- ^ Wm. Theodore de Bary; Richard Lufrano (1 June 2010). Sources of Chinese Tradition: Volume 2: From 1600 Through the Twentieth Century. Columbia University Press. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-231-51799-7. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Yunli Shi (January 2003), "The Korean Adaptation of the Chinese-Islamic Astronomical Tables", Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 57 (1), Springer: 25–60 [26], doi:10.1007/s00407-002-0060-z, ISSN 1432-0657, S2CID 120199426

- ^ Farmer, Edward L., ed. (1995). Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. BRILL. p. 82. ISBN 9004103910. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ Jiang, Yonglin (2011). The Mandate of Heaven and The Great Ming Code. University of Washington Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0295801667. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ The Great Ming Code / Da Ming lu. University of Washington Press. 2012. p. 88. ISBN 978-0295804002. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Ebrey Buckley, P., Women and the Family in Chinese History (London: Routledge, 2003) 1134442920 p.170.

- ^ Patricia Ebrey, " Surnames and Han Chinese Identity, " in Melissa J. Brown, ed., Negotiating Ethnicities in China and Taiwan Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California. p. 25.

- ^ Guida, Donatella (2018). "Aliens and Emperors: Faithful Mongolian Officials in the Ming History" (PDF). Ming Qing Yanjiu. 22 (2): 125. doi:10.1163/24684791-12340025. hdl:11574/183660. S2CID 186876742.

- ^ Guida, Donatella (December 2016). "Dalu Yuquan E Gli Altri : Funzionari Mongoli aLLa Corte dei Ming" (PDF). Sulla Via del Catai. IX (14): 97. doi:10.1163/24684791-12340025. hdl:11574/183660. S2CID 186876742.

- ^ Robinson, David M. (June 2004). "Images of Subject Mongols Under the Ming Dynasty". Late Imperial China. 25 (1). the Society for Qing Studies and The Johns Hopkins University Press: 75–6. doi:10.1353/late.2004.0010. S2CID 144527758.

- ^ Tan Ta Sen; Dasheng Chen (2000). Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 170. ISBN 978-981-230-837-5. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Shoujiang Mi; Jia You (2004). Islam in China. China Intercontinental Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-7-5085-0533-6. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Zhu, Yuanzhang. "皇明祖訓 - 维基文库,自由的图书馆". zh.wikisource.org (in Chinese). Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Edward L. Dreyer (1982). Early Ming China: a political history, 1355–1435. Stanford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-8047-1105-0. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Kenneth Warren Chase (2003). Firearms: a global history to 1700. Cambridge University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis; Fairbank, John K., eds. (1988). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644. Contributors Denis Twitchett, John K. Fairbank (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0521243322. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ Wang, Yuan-kang (19 March 2012). "Managing Regional Hegemony in Historical Asia: The Case of Early Ming China". The Chinese Journal of International Politics. 5 (2): 136. doi:10.1093/cjip/pos006.

- ^ Wang Gungwu, "Ming Foreign Relations: Southeast Asia," in Cambridge History of China, volume 8, pp, 301, 306, 311.

- ^ David Chan-oong Kang (2007). China Rising: Peace, Power, and Order in East Asia. Columbia University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-231-14188-8. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Li Kangying (2010), The Ming Maritime Trade Policy in Transition, 1368 to 1567, Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, p. 11, ISBN 9783447061728.

- ^ a b c Li (2010), p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Li (2010), p. 13.

- ^ Li (2010), p. 12.

- ^ Li (2010), p. 3.

- ^ a b c Li (2010), p. 4.

- ^ Li (2010), p. 168.

- ^ Farmer, Edward L. (1995). Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society. BRILL. p. 120. ISBN 978-9004103917. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Paul Halsall (2000) [1998]. Jerome S. Arkenberg (ed.). "East Asian History Sourcebook: Chinese Accounts of Rome, Byzantium and the Middle East, c. 91 B.C.E. – 1643 C.E." Fordham.edu. Fordham University. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ R. G. Grant (2005). Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat. DK Pub. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-0-7566-1360-0.

- ^ Friedrich Hirth (1885). China and the Roman Orient: Researches into Their Ancient and Mediaeval Relations as Represented in Old Chinese Records. G. Hirth. p. 66. ISBN 9780524033050.

- ^ Edward Luttwak (1 November 2009). The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire. Harvard University Press. pp. 170–. ISBN 978-0-674-03519-5.

- ^ 孙冰 (2010). "明代宫妃殉葬制度与明朝"祖制"". 《华中师范大学研究生学报》 (4). Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

按太祖孝陵。凡妃殡四十人。俱身殉从葬。仅二人葬陵之东西。盖洪武中先殁者。

- ^ 李晗 (2014). "明清宫人殉葬制度研究". 《山东师范大学》. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Ebrey, "Cambridge Illustrated History of China", pg. 190

- ^ Simon Leys, 'Ravished by Oranges' in New York Review of Books 20 December 2007 p.8

- ^ CHAN, HOK-LAM (2007). "Ming Taizu's Problem with His Sons: Prince Qin's Criminality and Early-Ming Politics" (PDF). Asia Major. 20 (1): 45–103.

This article incorporates text from China and the Roman Orient: researches into their ancient and mediæval relations as represented in old Chinese records, by Friedrich Hirth, a publication from 1885, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from China and the Roman Orient: researches into their ancient and mediæval relations as represented in old Chinese records, by Friedrich Hirth, a publication from 1885, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Cathay and the way thither: being a collection of medieval notices of China, by COLONEL SIR HENRY YULE, a publication from 1913, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Cathay and the way thither: being a collection of medieval notices of China, by COLONEL SIR HENRY YULE, a publication from 1913, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Institutes of ecclesiastical history: ancient and modern ..., by Johann Lorenz Mosheim, James Murdock, a publication from 1832, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Institutes of ecclesiastical history: ancient and modern ..., by Johann Lorenz Mosheim, James Murdock, a publication from 1832, now in the public domain in the United States.

Further reading

[edit]- Anita M. Andrew; John A. Rapp (1 January 2000). Autocracy and China's Rebel Founding Emperors: Comparing Chairman Mao and Ming Taizu. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 110–. ISBN 978-0-8476-9580-5. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Brook, Timothy. (1998). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22154-0 (Paperback).

- John W. Dardess (1983). Confucianism and Autocracy: Professional Elites in the Founding of the Ming Dynasty. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04733-4.

- John W. Dardess (1968). Background Factors in the Rise of the Ming Dynasty. Columbia University.

- Dreyer, Edward. (1982). Early Ming China: A Political History. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1105-4.

- Stearns, Peter N.; et al. (2006). World Civilizations: The Global Experience. AP Edition DBQ Update. New York: Pearson Education, Inc.

- "Chapter. 1–3". History of Ming.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Hongwu Emperor at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hongwu Emperor at Wikimedia Commons

![]() Quotations related to Hongwu Emperor at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Hongwu Emperor at Wikiquote

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch