Monongah, West Virginia

Monongah, West Virginia | |

|---|---|

Bridge Street | |

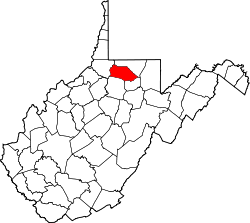

Location of Monongah in Marion County, West Virginia. | |

| Coordinates: 39°27′45″N 80°13′06″W / 39.46250°N 80.21833°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | West Virginia |

| County | Marion |

| Incorporated | 1891 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | John E. Palmer, Jr. |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.53 sq mi (1.38 km2) |

| • Land | 0.49 sq mi (1.26 km2) |

| • Water | 0.04 sq mi (0.12 km2) |

| Elevation | 961 ft (293 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 972 |

• Estimate (2021)[2] | 993 |

| • Density | 2,354.51/sq mi (909.01/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 26554-26555 |

| Area code | 304 |

| FIPS code | 54-55276[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1555149[4] |

| Website | Official Website |

Monongah is a town in Marion County, West Virginia, United States, situated where Booths Creek flows into the West Fork River. The population was 972 at the 2020 census.[2] Monongah was chartered in 1891. Its name is derived from the nearby Monongahela River.[5]

History

[edit]The Adena and Hopewell peoples dwelt in what is now northern West Virginia 1,500–2,000+ years ago. By the time of the early European traders and settlers, the native population is thought to have been nil, decimated by the Beaver Wars.[citation needed]

Monongah was known as Briar Town and was part of the Grant Magisterial District in 1886.[6][7]

It was later known as Camdensburg, named after Johnson N. Camden, United States Senator from West Virginia (1881–1887).[7] The Protestant Episcopal Church at Camdensburg described Camdensburg in 1889 as "a new mining and coking town which promises to be a place of some importance in a few years."[8]

Monongah was chartered in 1891 under Chapter 47 of West Virginia code, Of Cities, Towns, and Villages, Incorporation of Without Special Charter; Amending Charter Where Population Less Than Two Thousand.[9][10]

Monongah mining disaster

[edit]Monongah suffered the loss of all 358 miners underground and an engineer on the surface when Fairmont Coal Company Mines No 6 and No 8 exploded at 10:30 am on December 6, 1907. The dead consisted of 171 Italians, 85 Americans, 52 Hungarians, 31 Russians, 15 Austrians, and 5 Turks. Three more people died in the aftermath, yielding a total of 361 victims. This mining accident left approximately 250 widows and 500 fatherless children.[citation needed]

Mayor W.H. Moore, along with D.F. Morris, William Gaskins, and John Boydoh served on the Monongah Relief Committee, formed soon after to help manage the aid effort. Mayor Moore headed the Monongah Mines Relief Committee after Monongah and Fairmont decided to merge their committees into a joint effort.[11]

Memorials were erected in the center of town to recognize the centennial of the mining disaster on December 7, 2007. One memorial, titled Monongah Heroine, consists of a statue of a mother holding a baby with a young child beside her. It is dedicated to the widows and mothers of the miners who died. The inspiration for the statue is reported to have come from Catarina Davia, a woman widowed by the disaster.[citation needed] Feeling betrayed by the coal company for lack of compensation after her husband's death she vowed to make the 1.3 mile trek from her home to the mine to steal a satchel of coal every day until she died. She didn't only do this once every day but she did it twice. Her house was still standing until an accidental fire burned the house down on September 10, 2010. A second memorial, consisting of an engraved metal bell and plaque, was placed by the Italians to recognize the many victims from Molise in southern Italy.[citation needed]

Father Everett Francis Briggs, a Roman Catholic missionary of the Maryknoll order, oversaw the memorial project and died just a few days after its completion. On February 21, 2002, the West Virginia Legislature (House Concurrent Resolution no. 40) resolved "to name the bridge which traverses the West Fork River in Marion County, located .12 miles west of county route 27/2, the Father Everett Francis Briggs Bridge", in honor of Briggs' dedication to the forgotten victims of the 1907 tragedy and the mine widows.[citation needed]

Geography

[edit]Monongah is located at 39°27′45″N 80°13′06″W / 39.46250°N 80.21833°W (39.4625, −80.2183).[12]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 0.53 sq mi (1.37 km2), of which 0.49 sq mi (1.27 km2) is land and 0.04 sq mi (0.10 km2) is water.[13]

For such a small community, Monongah consists of many villages or named neighborhoods. These include East Monongah, Brookdale, Traction Park, Thoburn, Tower Hill and West Monongah. Prior to being incorporated and named "Monongah," the town was called "Briartown." It is often considered to be the unofficial capital of small coal mining towns.

Not only does the West Fork (of the Monongahela River) run through the middle of Monongah but Booths Creek (named for Continental Army James Booth, who was killed by Native Americans in 1778) joins the West Fork in Monongah.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 1,786 | — | |

| 1910 | 2,084 | 16.7% | |

| 1920 | 2,031 | −2.5% | |

| 1930 | 1,909 | −6.0% | |

| 1940 | 1,790 | −6.2% | |

| 1950 | 1,622 | −9.4% | |

| 1960 | 1,321 | −18.6% | |

| 1970 | 1,194 | −9.6% | |

| 1980 | 1,132 | −5.2% | |

| 1990 | 1,018 | −10.1% | |

| 2000 | 939 | −7.8% | |

| 2010 | 1,044 | 11.2% | |

| 2020 | 972 | −6.9% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 993 | [2] | 2.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[15] of 2010, there were 1,044 people, 457 households, and 301 families living in the town. The population density was 2,130.6/sq mi (822.6/km2). There were 494 housing units at an average density of 1,008.2/sq mi (389.3/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 94.8% White, 3.5% African American, 0.1% Native American, 0.2% Asian, 0.5% from other races, and 0.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.0% of the population.

There were 457 households, of which 26.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.6% were married couples living together, 13.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.9% had a male householder with no wife present, and 34.1% were non-families. 30.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.28 and the average family size was 2.81.

The median age in the town was 42 years. 19.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 7.2% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 27.6% were from 25 to 44; 27.8% were from 45 to 64; and 18.4% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the town was 50.5% male and 49.5% female.

2000 census

[edit]As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 939 people, 406 households, and 263 families living in the town. The population density was 1,977.0 inhabitants per square mile (771.4/km2). There were 443 housing units at an average density of 932.7 per square mile (363.9/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 91.91% White, 5.64% African American, 0.11% Asian, and 2.34% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.32% of the population.

There were 406 households, out of which 24.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.5% were married couples living together, 10.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.0% were non-families. 32.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 17.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.31 and the average family size was 2.92.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 21.0% under the age of 18, 8.8% from 18 to 24, 26.9% from 25 to 44, 25.1% from 45 to 64, and 18.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.7 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $25,750, and the median income for a family was $33,000. Males had a median income of $25,417 versus $19,722 for females. The per capita income for the town was $14,079. About 12.2% of families and 15.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.9% of those under age 18 and 17.0% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

[edit]Fairmont Coal Company, of Fairmont, West Virginia, bought 36 mines in June 1901, including six mines of the Monongah Company.[16]

The town's local cement block factory went out of business in 2002 and was torn down in 2003.[citation needed]

The broadcast tower for the Fairmont AM radio station, WMMN, was constructed in the middle 1930s atop Tower Hill in Monongah.[17]

The town is featured in the post-apocalyptic video game Fallout 76.

Education

[edit]Monongah High School was merged with the public high school populations of Mannington, Barrackville, and Fairview, West Virginia in 1979 to form North Marion High School, located in Farmington, West Virginia. North Marion was constructed to replace Farmington High School, which closed in 1975.

The Saints Peter and Paul School was a K-8 parochial school operated in Monongah by the Sisters Auxiliaries of the Apostolate Society, a Roman Catholic society of apostolic life founded in Wheeling, West Virginia on December 15, 1937, and terminated August 26, 2013.[18] The school and surrounding buildings were demolished in August 2011.[19]

Notable people

[edit]- Ruth Broe, one of the first women to join the United States Marine Corps

- Sam "Toothpick" Jones, Major League Baseball pitcher

- Roman Prezioso, West Virginia state senator

- Nick Saban, sportscaster and former American football coach

References

[edit]- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021". Census.gov. US Census Bureau. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 212.

- ^ Marion and Monongahela Counties, 1886: D J Lake Company Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, historicmapworks.com; accessed June 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Marion County GenWeb Archived December 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, wvgenweb.org; accessed June 18, 2017.

- ^ "Thirteenth Annual Council of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of West Virginia, held in St John's Church, Charleston, June 4, 5, 6 and 7, 1890, Appendix B, pg 104 (628/672)". Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ^ "West Virginia Blue Book". June 19, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hogg's West Virginia Code, Annotated, 1918, books.google.com; accessed June 18, 2017.

- ^ History of the Monongah Mines Relief Fund, pp 9–10, books.google.com; accessed June 18, 2017.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ "Fairmont Coal Company Story". Einhorn Press. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ In 2004, Jack Meredith (1925–2007) recorded his recollections of growing up on Tower Hill, including the story of how he helped dig the ditches that electrically connected the three WMMN broadcast towers. http://don.homelinux.net/~don1/TowerHill/jack_text.html[permanent dead link]

- ^ West Virginia Companies http://www.companies-westvirginia.com/sisters-auxiliaries-of-the-apostolate-society-khd/ Archived August 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Times WV, It's A Sad Day http://www.timeswv.com/local/x890682521/-It-s-a-sad-day Archived December 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch