Mount Pindo

| Mount Pindo | |

|---|---|

| Celtic Olympus | |

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 627 m (2,057 ft) |

| Coordinates | 42°53′19″N 09°06′47″W / 42.88861°N 9.11306°W |

| Geography | |

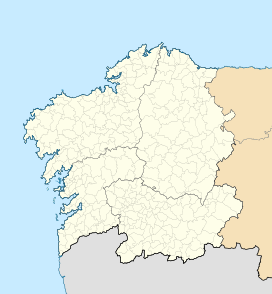

Mount Pindo (Galician: Monte Pindo) is a mountain located in the autonomous community of Galicia, Spain. It is in the municipality of Carnota and province of A Coruna.[1] Composed of granite, it has a height of 627m. It is of local mythological importance.

Geography

[edit]Mountain is located in the Atlantic coast near Carnota. Mountain prevent connections between villages.

Since 2014 it is part of Natura 2000 special area of conservation of Monte Pindo and Carnota. The area covers 4674 hectares. A number or rare animals live in the area, including otter, many bats, black-throated loon and peregrine falcon.[2] Local environmentalists are campaigning to develop the area to full nature park.[3]

In 2013 there was a devastating wildfire at Monte Pindo. It burned more than 1600 hectares of forest.[4]

History

[edit]There is evidence of human presence from 6000 years ago in form of ceramic findings.[3] In 10th century bishop of Iria Flavia ordered a castle to be built on slopes of the mountain to protect the area from attacks from the sea. The castle was occupied by several noble families of Galicia until it was destroyed in the 1467 war. After that treasure hunters have destroyed the remaining walls.[5]

The particular geomorphology of Mount Pindo, full of reliefs in granite bowls, inspired many stories and legends of deities, carvings, or mythical monsters and giants, including some on the river Xallas, because the waterfall Ézaro fall by its waters directly on the salt water of the sea. It found numerous archaeological remains, as petroglyphs helpful bronze and remains of a supposed old hermitage.

In the tenth century Sisnando (bishop of Iria Flavia) ordered the construction of the Castle of St. George on the shores of the mountain as protection against pirate attacks medieval. Several noble families of Galicia inhabited until the castle was destroyed in 1467 in Irmandiñas Revolutions.

In this environment would be other two castles, but one that does not retain material remains determinants or documentation parsable more than a Latin inscription on a stone isolated: Kings, bishops, priests, by all powers received from God, this castle here excomungaron

This inscription refers to excommunication that in 1130 launched the archbishop Gelmírez against Earl Lock, to have prisoner in his castle to the Archdeacon of Castile.

Another fort on the mountain was called Peñafiel: there have also been hermitages, wells and paths. During the Spanish Civil War mountain was used as a refuge to escape from the enemy.[6]

Etymology

[edit]The term Pindo has its origin in the language most likely Celtic: Binn dubh (Mt. dark, dark top).[7] The name Pindo may arise from the dialect of Gaelic Celtic spoken in the area before the Romanization of Gallaecia:[8] Binn (Irish Gaelic) or beinn (Gaelic) (literally tip or apex) and dubh (adjective to describe something dark). Binn Dubh (pindub) amount after Pindo. The Romans gave, however, the name of Celtic Supertamarci (which refers to celtización the area).

The authors also provide several examples of physically similar to the hills of Carnot and called exactly that way in both Ireland (Monte Binn Dubh), as in Scotland (Beinn Dubh Monte).

Mythology

[edit]The mountain is regarded as mythical place. Several legends are related to celts which occupied the area in ancient times. It is said the mountain was their Mount Olympos where they made sacrifices. The lush nature connects the place to fertility, which has encouraged pilgrimage of couples wishing to get more children.[9][10]

Some caves in the area are said to belong to mouros, the supernatural beings living underground.[11]

Queen Lupa is said to be buried at the Castle of Saint George, on Mount Pindo.[12][13]

Name

[edit]There are numerous legends about this mountain, which some romantic Galician historians considered the Celtic Olympus.

Its dark color is one of the main characteristics of Pindo.

Place-names often reflect the topographic features characteristic of a given area, and such descriptive place-names are common in the indigenous languages of the different areas of the world.

Since Galicia has always been considered a land occupied by the ancestors of the local inhabitants over countless generations, without massive immigration of outsiders, a large number of Galician place-names should reflect similar descriptive toponyms.

However, in addition to place-names easily decipherable in the Galician language, we find place-names which allow no easy interpretation. As in other areas of the globe, such unintelligible place-names may reflect languages spoken earlier in the region, but which have later died out, leaving the descriptive place-names unintelligible in the present-day languages of the area.

Since Galicia was clearly a Celtic region at the time of the Roman conquest, let us have a look at the place-name Pindo from the perspective of the Celtic languages – more specifically from the perspective of the Goidelic or Gaelic branch of the Celtic languages.

In Irish Gaelic, binn means “peak”, “mountain top” and, by extension, at times it is used in reference to a mountain. In Scottish Gaelic, beinn also means “peak”, “mountain top” and, by extension, at times it is used in reference to a mountain too.

In Irish Gaelic, however, the sound represented by the letter b retains its voicing. Thus, the sound is quite similar to a Galician b /b/ in word-initial position. This, however, can be deceptive in the written languages, since the Galician b lenites to a soft sound like /v/ in word-medial or word-final position, while the Irish letter b is not lenited in such positions.

In Scottish Gaelic, b is pronounced as the unvoiced, unaspirated consonant /p/, very similar to the Galician consonant p /p/.

In both Gaelic languages, dubh means “dark”. In Northern Irish dialects and in Scottish Gaelic, the final consonant, pronounced like the Spanish consonant b inter-vocalically and represented by the digraph bh, is elided. Therefore, the word dubh is pronounced /du/.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ The share is higher Moa peak (627 meters), 'Great Galician Encyclopedia Silverio Cañada' 'DVD.

- ^ "Carnota - Monte Pindo (ES1110008)". Natura 2000. European Environment Agency.

- ^ a b Monte Pindo, Parque Natural! Adega.

- ^ Monte Pindo wildfire threatens another unique Galicia beauty spot El Pais 2013

- ^ Castelo de San Xurxo Patrimonio Galego

- ^ Assessment and Management of the Geomorphological Heritage of Monte Pindo (NW Spain): A Landscape as a Symbol of Identity | Manuela Costa-Casais, María Isabel Caetano Alves and Ramón Blanco-Chao, Sustainability / MDPI (page 20 / 7068)

- ^ Progael.com "Artigo sobre a etimoloxía do termo Pindo"

- ^ According to the research doctor in linguistics from Stanford University in the US: James J. Duran, Ph. D. (Séamas Direáin O), or licensed in Geography and History from the University of Santiago de Compostela: Alberto Villaverde Lake and more than Henrique Egea Lapina, graduated in Classical Philology at the University of Santiago de Compostela,

- ^ "Mirador Monte Pindo". Turismo de Galicia. 2013.

- ^ NATALIA, KLIMCZAK (2016-02-13), "Monte Pindo: A Legendary Celtic Olympus from Ancient Galicia", Ancient Origins

- ^ "Myths, legends and beliefs on granite caves" (PDF). Cadernos Lab. Xeolóxico de Laxe Coruña. 2008. pp. 19–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-19.

- ^ "Pindo Mountain". visitacostadamorte.com. Retrieved 2023-02-06.

- ^ Stanton, Edward F. (1994). The Road of Stars to Santiago. The University of Kentucky Press. p. 192. ISBN 9780813118710.

- ^ "Micro-Docs". www.progael.com. Archived from the original on 2015-06-13.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch