Mughal artillery

| Part of a series on |

| Cannons |

|---|

|

Mughal artillery included a variety of cannons, rockets, and mines employed by the Mughal Empire. This gunpowder technology played an important role in the formation and expansion of the empire. In the opening lines of Abul Fazl's famous text Ain-i-Akbari, he claims that "except for the Mediterranean/Ottoman territories (Rumistan), in no other place was gunpowder artillery available in such abundance as in the Mughal Empire."[1] Thereby subtly referring to the superiority of the empire's artillery[2] over the Safavids and Shaibanids. During the reign of the first three Timurid rulers of India—Babur, Humayun, and Akbar—gunpowder artillery had "emerged as an important equipage of war, contributing significantly to the establishment of a highly centralized state structure under Akbar and to the consolidation of Mughal rule in the conquered territories."[1]

Mughal commanders such as Mir Jumla II was noted for their shared traits of Asian lords for their fondness for cannon artilleries, and how he is willing to employ European engineers such as crews of a vessel named Ter Schelling.[3]

History

[edit]

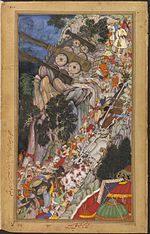

Artillery was not widely employed in Central Asia prior to the 16th century, despite Chinese mortars having been known to the Mongols hundreds of years earlier. Even some use of cannon at Hisar by the Timurid Sultan Husayn Mirza in 1496 did not lead to a substantial military role for artillery in India,[5] nor did the presence of Portuguese ship's cannon at the 1509 Battle of Diu.[6] However, following the decisive Ottoman victory over the Safavid Empire at the 1514 Battle of Chaldiran, Babur incorporated artillery and Ottoman artillery tactics into his military.[5] Although authorities disagree about how many cannons he brought to India,[7] Babur's artillery played a "key role" in the establishment of the Mughal Empire.[8] In 1526, the First Battle of Panipat saw the introduction of massed artillery tactics to Indian warfare.[7] Under the guidance of Ottoman gun master[5] Ustad Ali Quli, Babur deployed cannons behind a screening row of carts. Enemy commander Ibrahim Lodi was provoked into a frontal attack against Babur's position, allowing him to make ideal use of his firepower.[9][10] This tactic also panicked Lodi's elephant cavalry, beginning the end of elephant warfare as a dominant offensive strategy in India.[7] These new weapons and tactics were even more important[9] against the more formidable army faced in the Battle of Khanwa the following year.[7]

Artillery remained an important part of the Mughal military, in both field deployment and incorporation into defensive forts. However, transportation of the extremely heavy guns remained problematic,[9] even as weapon technology improved during the reign of Akbar.[11] In 1582, Fathullah Shirazi, a Persian-Indian Mughal officer, developed a seventeen-barrelled cannon, fired with a matchlock.[12] Shirazi also invented an anti-infantry volley gun with multiple gun barrels similar to a hand cannon.[13]

Later emperors paid less attention to the technical aspects of artillery, allowing the Mughal Empire to gradually fall behind in weapon technology,[14] although the degree to which this decline affected military operations is debated.[11] Under Aurangzeb, the Mughal technology remained superior to that of the breakaway Maratha Empire,[7] but traditional Mughal artillery tactics were difficult to employ against Maratha guerrilla raids.[15] In 1652 and 1653, during the Mughal–Safavid War, prince Dara Shikoh was able to move light artillery through the Bolan Pass to assist in the siege of Qandahar.[11] But problems with the accuracy and reliability of the weapons,[14] as well as the inherent defensive strengths of the fort,[16] failed to produce a victory. By the 18th century, the bronze guns of the declining empire were unable to compete with the standardized production of European cast-iron weapons[11] and performed poorly against colonial forces, such as Jean Law de Lauriston's French troops.[17]

Weaponry

[edit]

archaeological research has recovered guns made of bronze from Kozhikode which dated from 1504 and Diu, India which dated from 1533.[18]

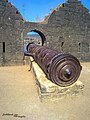

Mughal cannon making skills advanced during the 17th century.[19] One of the most impressive Mughal cannons is known as the Zafarbaksh, which is a very rare composite cannon, that required skills in both wrought-iron forge welding and bronze-casting technologies and the in-depth knowledge of the qualities of both metals.[20] Some devices to support the maintenance also developed, such as and A machine invented by Mughal officer, Fathullah Shirazi, known as "Yarghu" which could clean sixteen gun barrels simultaneously and was operated by a cow.[21] Shirazi also developed an early multi-gun shot. Unlike the polybolos and repeating crossbows which used in ancient Greece and China respectively, Shirazi's rapid-firing hand cannon had multiple gun barrels that fired gunpowder, akin to volley gun.[22]

The Ibrahim Rauza was a famed cannon, which was well known for its multi-barrels.[23] François Bernier, the personal physician to Aurangzeb, observed Mughal gun-carriages each drawn by two horses, an improvement over the bullock-drawn gun-carriages used elsewhere in India.[24]

Despite these innovations, most soldiers used bows and arrows, the quality of sword manufacture was so poor that they preferred to use ones imported from England, and the operation of the cannons was entrusted not to Mughals but to European gunners. Other weapons used during the period included rockets, cauldrons of boiling oil, muskets and manjaniqs (stone-throwing catapults).[25]

- Daulatabad cannon

- Kalak Bangadi cannon.

- One of the Daulatabad cannons

- Kilkila cannon

- Aurangabad cannon

The Mughal military employed a broad array of gunpowder weapons larger than personal firearms, from rockets and mobile guns to an enormous cannon, over 14 ft (4.3 m), once described as the "largest piece of ordnance in the world."[26] This array of weapons was divided into heavy and light artillery.[11][26][1] According to historian Irfan Habib, one cannot "estimate the amount of metal used in the artillery of the Mughal army, or the amount of gunpowder it consumed, but in view of the numbers employed in the artillery (over 40,000 men), it is certain that at any time some tens of thousands of matchlocks (surely not less than 25,000, on these numbers) must have been in use; and we know that excessively heavy cannon were much favored in India."[27]

Heavy artillery

[edit]Extremely heavy artillery was an important part of the Mughal military, especially under its early emperors.

Emperor Babur reportedly deployed guns capable of firing cannonballs weighing between 225 and 315 lb (102 and 143 kg) against a 1527 siege, and had previously employed a cannon capable of firing a 540 lb (240 kg) stone ball. Humayun did not field such massive artillery at the Battle of Kannauj in 1540, but still had heavy cannons, capable of firing 46 pound lead balls at a distance of one farsakh.[29] These large weapons were often given heroic names, such as Tiger Mouth (Sher Dahan), Lord Champion (Ghazi Khan), or Conqueror of the Army (Fath-i-Lashkar),[26][30] and inscriptions, sometimes in verse. They were not only weapons, but "real works of art".[29] Their artistry did not make them easier to move, however. Rugged passes and water crossings were insurmountable barriers,[26] and even when they could be moved, it was a slow process requiring sixteen[29] or twenty oxen for relatively moderate cannons such as Humayun's. Muhammad Azam Shah was forced to abandon his heavy artillery en route to the Battle of Jajau.[26] The largest such weapons, such as Muhammad Shah's "Fort Opener", required a team of "four elephants and thousands of oxen" and only rarely reached their siege targets.[31]

Other heavy artillery used by the Mughals are Wökhul[32] (mortars).[11][26] The largest recorded Mughal mortar was designed by Shirazi, which used during the Siege of Chittorgarh were capable firing a cannonball as heavy as 3,000 lbs.[33] Mines also deployed by sappers against fortress walls.[26] Although these weapons had noticeable successes, such as the victory at the Siege of Chittorgarh in 1567, their preparation and deployment came at the cost of substantial Mughal losses.[29] [34] Another recorded mortar usage also recorded in 1659 during the conflict between Aurangzeb against his brother, Shah Shuja.[35][36]

The Mughals artillery corps employed hand grenades[26] and rocket artillery.[37]: 48 [38]: 133 Under Akbar's reign, Mughal rockets began to use metal casing, which made them more weatherproof and allowed a larger amount of gunpowder, increasing their destructive power.[37]: 48 Mughal ban iron rockets were described by European visitors, including François Bernier who witnessed the 1658 Battle of Samugarh fought between brothers Aurangzeb and Dara Shikoh.[38]: 133 Mughal rockets are considered a predecessor to the Mysorean rockets later employed by Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan in the 18th century.

By the 17th century, Indians were manufacturing a diverse variety of firearms; large guns in particular, became visible in Tanjore, Dacca, Bijapur and Murshidabad.[39]

Light artillery

[edit]

Mughal light artillery, also known as artillery of the stirrup,[11][16] consisted of a variety of smaller weapons. Animal-borne swivel guns saw widespread use in several forms.[14] Elephants carried two pieces of "elephant barrel" (gajnal and hathnal) artillery and two soldiers to fire them. The elephants served only to transport the weapons and their crew, however, they dismounted before firing. "Camel guns" (shutarnal or zamburak) and "swivel guns" on the other hand were carried on camel-back and were fired while mounted.[26] Other light guns were mounted on wheeled carts, pulled by oxen[26] or horses.[6]

The mobile field artillery has been seen as the central military power of the Mughal empire distinguishing the Mughal troops from most of their enemies. A status symbol for the emperor, pieces of artillery would always accompany the Mughal emperor on his journeys through the empire. The Mughal artillery's main use in battle was to counter hostile war elephants which were common in warfare on the Indian subcontinent. But although emperor Akbar personally used to design gun carriages to improve the accuracy of his cannons, the Mughal artillery was most effective by scaring the opponent's elephants off the battlefield. The ensuing chaos in the hostile ranks would enable the Mughal armies to defeat the enemy's troops.[40]

Grenadiers and rocket-bearing soldiers were also considered part of the Mughal light artillery.[26] The Mughals artillery corps employed rockets,[37]: 48 [38]: 133 which are considered as predecessor of Mysorean rockets that employed by Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan[41] Despite it packs considerable punch on the battlefield, the rocket are qute lightweight and easy to transport, as it was recorded that a camel can carry up to 20 Mughal rockets.[37] During Akbar reign, he ordered many rockets as it is recorded that he once ordered 16,000 rockets for a single garrison.[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2009). "Nature of Gunpowder Artillery in India during the Sixteenth Century – a Reappraisal of the Impact of European Gunnery". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 9 (1). Cambridge University Press: 27–34. doi:10.1017/S1356186300015911 – via Cambridge Core.

- ^ Athar Ali, M (1971). "Presidential Address". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 33. Indian History Congress: 175–188. JSTOR 44145330 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Francisco Bethencourt & Cátia A.P. Antunes (2022, p. 116)

- ^ unknown (1590s). "1526, First Battle of Panipat, Ibrahim Lodhi and Babur". Baburnama.

- ^ a b c Adle C, Habib I, Baipakov KM, eds. (2004). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in Contrast : from the Sixteenth to the Mid-Nineteenth Century. United Nations Educational. pp. 474–475. ISBN 978-9231038761.

- ^ a b Grant RG. (2010). Warrior: A Visual History of the Fighting Man. DK ADULT. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-0756665418.

- ^ a b c d e Barua PP. (2005). The State at War in South Asia. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803213449.

- ^ Kinard J. (2007). Artillery: An Illustrated History of Its Impact. ABC-CLIO. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-1851095568.

- ^ a b c Archer CI, Ferris JR, Herwig HH, Travers THE (2002). World History of Warfare. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 182–195. ISBN 978-0803244238.

- ^ Singh H. (2011). Cannons Versus Elephants: The Battles of Panipat. Pentagon Press. ISBN 978-8182745018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gommans JJL. (2002). Mughal Warfare: Indian Frontiers and Highroads to Empire 1500-1700. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415239899.

- ^ Clarence-Smith, William Gervase, Science and technology in early modern Islam, c.1450-c.1850 (PDF), Global economic history network, London School of Economics, p. 7

- ^ Bag, A. K. (2005), Fathullah Shirazi: Cannon, Multi-barrel Gun and Yarghu, Indian Journal of History of Science, pp. 431–436.

- ^ a b c Richard JF. (1996). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 288–289. ISBN 978-0521566032.

- ^ Chaurasia RS. (2011). History of Modern India: 1707 A.D. to 2000 A.D. Atlantic Publishers. p. 7. ISBN 978-8126900855.

- ^ a b Chandra S. (2000). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals, Volume 2 (Revised ed.). Har-Anand. p. 228. ISBN 978-81-241-1066-9.

- ^ Ragani S. (1988) [1st. pub. 1963]. Nizam-British Relations 1724-1857. Concept Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 978-81-7022-195-1.

- ^ Partington, James Riddick (1999) [First published 1960]. A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0.

- ^ Singh, Abhay Kumar (2006). Modern World System and Indian Proto-industrialization: Bengal 1650–1800. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Northern Book Centre. pp. 351–352. ISBN 978-81-7211-201-1. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ Balasubramaniam, R.; Chattopadhyay, Pranab K. (2007). "Zafarbaksh – The Composite Mughal Cannon of Aurangzeb at Fort William in Kolkata" (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. 42. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015.

- ^ Alvi, M.A.; Rahman, Abdur (1968). Fathullah Shirazi: A Sixteenth Century Indian Scientist. New Delhi: National Institute of Sciences of India.

- ^ Bag, A.K. (2005). "Fathullah Shirazi: Cannon, Multi-barrel Gun and Yarghu". Indian Journal of History of Science. 40 (3): 431–436. ISSN 0019-5235.

- ^ Douglas, James (1893). Bombay and western India: a series of stray papers. Vol. 2. Sampson Low, Marston & Company.

- ^ Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2006). "The Indian Response to Firearms, 1300-1750". In Buchanan, Brenda J. (ed.). Gunpowder, Explosives And the State: A Technological History. Ashgate Publishing. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-7546-5259-5.

- ^ Partington, James Riddick (1998) [1960 (Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons)]. A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 221. ISBN 9780801859540.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Irvine W. (1903). The Army Of The Indian Moghuls: Its Organization And Administration. Luzac. pp. 113–159.

- ^ Habib, Irfan (2011). "Potentialities of Capitalistic Development in the Economy of Mughal India". The Journal of Economic History. 29 (1). Cambridge University Press: 32–78. doi:10.1017/S0022050700097825 – via Cambridge Core.

- ^ Unknown (1590–95). "Bullocks dragging siege-guns up hill during Akbar's attack on Ranthambhor Fort". the Akbarnama. Archived from the original on 2014-05-19. Retrieved 2014-05-19.

- ^ a b c d Schimmel A. (2004). The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture. Reaktion Books. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-1861891853.

- ^ Mason P. (1974). A Matter of Honour: An Account of the Indian Army, Its Officers and Men. Jonathan Cape Limited. p. 47. ISBN 978-0224009782.

- ^ Smith BG, Van De Mieroop M, von Glahn R, Lane K (2012). Crossroads and Cultures: A History of the World's Peoples. Bedford/St. Martin's. pp. 627–628. ISBN 978-0312410179.

- ^ James Prinsep (2007, p. 294)

- ^ Eric G. L. Pinzelli (2022). Masters of Warfare Fifty Underrated Military Commanders from Classical Antiquity to the Cold War. Pen & Sword Books. pp. 140–142. ISBN 9781399070157. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ Asiatic Society, Asiatic Society of Bengal (2007). Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Volume 65, Part 1. Kolkata, India: Asiatic Society of Bengal. p. 294. ISBN 978-9693519242. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ James Prinsep (2007). Sarkar, Jadunath (ed.). Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (first published in 1896). Vol. 65 part 1. Kolkata, India: Asiatic Society, Asiatic Society of Bengal. p. 187. ISBN 978-9693519242. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ William Irvine (2007). Sarkar, Jadunath (ed.). Later Mughals. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Kolkata, India: Asiatic Society, Asiatic Society of Bengal. p. 199. ISBN 978-9693519242. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Andrew de la Garza (2016). The Mughal Empire at War Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500-1605. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317245315. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Alfred W. Crosby (April 8, 2002). Throwing Fire Projectile Technology Through History (Hardcover). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521791588. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ Partington, James Riddick (1999) [First published 1960]. A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0.

- ^ Rothermund, Dietmar (2014). "Akbar 'Der Große'" [Akbar 'The Great']. Damals (in German). Vol. 46, no. 1. pp. 24–29.

- ^ "Will Slatyer (February 20, 2015). The Life/Death Rhythms of Capitalist Regimes - Debt Before Dishonour Timetable of World Dominance 1400-2100. Partridge Publishing Singapore. ISBN 9781482829617. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

rockets were upgraded versions of Mughal rockets utilised during the Siege of Jinji by the progeny of the Nawab of Arcot

Further reading

[edit]- Khan, Iqtidar Alam. (1991). "The Nature of Handguns in Mughal India: 16th and 17th Centuries." Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 52, 378–389. JSTOR 44142632

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam. (2004). Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India. Delhi, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195665260

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam. (2005). "Gunpowder and Empire: Indian Case." Social Scientist, 33(3/4), 54–65. JSTOR 3518112

- Nath, Pratyay. (2019). Climate of Conquest: War, Environment, and Empire in Mughal North India. Delhi, Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199495559.001.0001

- Roy, Kaushik. (2012). "Horses, guns and governments: A comparative study of the military transition in the Manchu, Mughal, Ottoman and Safavid empires, circa 1400 to circa 1750." International Area Studies Review, 15(2), 99–121. doi:10.1177/2233865912447087 Accessed here: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2233865912447087?journalCode=iasb

- Francisco Bethencourt; Cátia A.P. Antunes (2022). Merchant Cultures A Global Approach to Spaces, Representations and Worlds of Trade, 1500–1800. Brill. ISBN 9789004506572. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Mughal artillery at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mughal artillery at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch