Museo de América

Façade of the museum | |

| |

| Established | 1941 |

|---|---|

| Location | Madrid, Spain |

| Type | Art, archaeological, and ethnographic |

| Owner | General State Administration |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Museo de América |

| Type | Non-movable |

| Criteria | Monument |

| Designated | 1962 |

| Reference no. | RI-51-0001378 |

The Museo de América is an art, archaeology, and ethnography museum in Madrid, Spain, devoted to the whole of the Americas from the Paleolithic period to the present day. It is one of the National Museums of Spain and it is attached to the Ministry of Culture.

The museum was established by the Spanish State and its initial pieces came from the former collection of American archaeological and ethnographic artifacts from the National Archaeological Museum, Madrid and the Prado Museum, as well as exhibiting a number of unrelated donations, deposits and purchases.[1] It has a major collection of 18th c. casta paintings, one by Miguel Cabrera, who created a set of 16 large format casta paintings. The museum's most famous painting is by Mexican artist, Luis de Mena, of the Virgin of Guadalupe and castas on a single canvas.[2]

History

[edit]The Museo de América was founded in 1941, bringing together works that were in other repositories. Unfortunately, a fire at the Alcázar of Madrid in 1734 destroyed the American collections that the kings of Spain had been building, which included the pieces offered to the Crown by the conquistadors. There is evidence that only a small number of items were saved because they were found elsewhere, such as the codices and feather miters that are preserved in the Monastery of El Escorial and some Mexican codices that were in the Royal Library, now the National Library of Spain. Because of the fire and only scattered items from the early colonial era, the oldest collections in the Museum are those from the Royal Cabinet of Natural History, established by Charles III in 1771. These came largely from the donation of the collection that Pedro Franco Dávila had assembled during his stay of more than fourteen years in Paris. In order to increase the collection, this institution issued instructions to the territories of Spanish America for the collection and submission of representative works. These included items from the first archaeological excavations carried out in Spanish America. Ethnographic materials obtained in scientific and discovery expeditions were also incorporated into the Royal Cabinet.

In 1868 the collections of antiquities, art and ethnography of the Royal Cabinet (which in 1815 had been dissolved and integrated, along with other institutions, into the new Royal Museum of Natural Sciences of Madrid, a direct predecessor of the current National Museum of Natural Sciences) were transferred to the National Archaeological Museum, created the previous year, to which were added those of the Museum of Medals and Antiquities of the National Library, which had some American items, those of the Escuela Superior Diplomática and those of the Royal Academy of History. From the Archaeological Museum, in turn, those of American origin (until then in Section IV or Ethnography) would be separated by the Decree of creation of the Museum of America, of April 19, 1941. The decree stated that "The initial collection will consist of the collections of American Ethnography and Archaeology existing in the National Archaeological Museum, with their books, display cases and furniture". Although the founding decree did not mention them, the collections of the Philippines and Oceania were also incorporated in the new museum, as well as a small African collection and about a hundred Sámi objects that had been donated to the MAN in 1896 by the Swedish engineer Åke Sjögren.

Once the new museum was created, the collection was provisionally installed in a wing of the main floor of the National Archeological Museum, and was inaugurated on July 13, 1944.[3] There were only eleven rooms, seven dedicated to pre-Columbian collections and the other four to colonial-era collections. In 1962 the move to its final location began, in the Ciudad Universitaria. It was officially inaugurated three years later in 1965. The initial holdings were later moved to a newly built premises and the building was inaugurated on 12 October 1965.[4] After a series of renovations of the building, which was previously shared with a number of unrelated institutions, The Museum was closed between 1981 and 1994 due to renovation work. the museum was reopened on 12 October 1994, this time exclusively occupying the entire building.[5] As part of preparation for the re-opening, a collecting program was established, with artifacts from Spain's first Caribbean settlement on Hispaniola (modern Haiti and the Dominican Republic) found by anthropologist Soraya Aracena.[6] It is classified as an Asset of Cultural Interest with the category of monument by virtue of Decree 474/1962, of 1 March (Boletín Oficial del Estado of 9 March), by which certain museums were declared historic-artistic monuments.

Collection

[edit]The permanent exhibit is divided into five major thematic areas:

- An awareness of the Americas

- The reality of the Americas

- Society

- Religion

- Communication

- Ceramic vessel representing a crustacean. Moche culture artwork from Peru.

- Bronze helmet of a 16th-century Spanish soldier.

- Chimú vessel showing a sexual act between men.

- Helmet and collar made by the Tlingit people (late 18th century).[8]

- Statuette of a Quimbaya cacique (200–1000 AD)[9]

- Maya Stele of Madrid (600–900 AD)[11]

- Aztec Codex Tudela

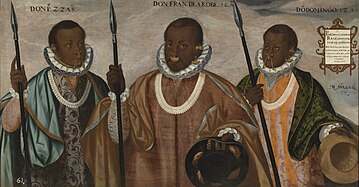

- The Mulattos of Esmeraldas, by Andrés Sánchez Gallque (Quito School), 1599 (depósito del Museo del Prado).

- Conquest of Mexico. Reception of Moctezuma by Mexicans in canoes, enconchado painting Juan y Miguel González, Mexican School, 1698 (depósito del Prado).

- Escena de mestizaje (Casta painting): De chino cambujo e india, loba. Miguel Cabrera, Mexican School, 1763.

- Yapanga of Quito with the dress that this class of women wore to please. Lienzo de Vicente Albán de 1783, Quito School.

See also

[edit]- Museo Nacional de Antropología (Madrid), also featuring American pieces

References

[edit]- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 84.

- ^ Sarah Cline, “Guadalupe and the Castas: The Power of a Singular Colonial Mexican Painting.” Mexican Studies/Esudios Mexicanos Vol. 31, Issue 2, Summer 2015, pages 218-46.;Bailey, Gauvin Alexander (2005). Colonial Art in Latin America. New York: PhaidonPress. pp. 66–68.;Bleichmar, Daniela (2012), Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 173;Deans-Smith, Susan (Winter 2005). "Creating the Colonial Subject: Casta Paintings, Collectors, and Critics in Eighteenth-Century Mexico and Spain". Colonial Latin American Review: 169–204.; Elena Isabel Estrada de Gerlero,"The Representation of ‘Heathen Indians’ in Mexican Casta Painting." In New World Orders, edited by Ilona Katzew. NY: Americas Society, 1996, 50.; María Concepción García Sáiz. Las castas mexicanas: un género pictórico americano. Milan: Olivetti, 1989, set III; 66–67; Ilona Katzew, Casta Paintings: Images of Race in Eighteenth-CenturyMexico. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004, 194–195; María Elena Martínez, Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008, dust cover; 257; Cruz Martínez de la Torre and María Paz Cabello Caro. Museo de América, exhibition catalogue. Madrid: IberCaja/Marot, 1997, 130; Jeanette Favrot Peterson, Visualizing Guadalupe: From Black Madonna to Queen of the Americas. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014, 256–257; Nina M. Scott, "Measuring Ingredients: Food and Domesticity in Mexican Casta Paintings." Gastronomica 5, no. 11 (2005): 70–79.

- ^ Krizmanics 2018, p. 40.

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 89.

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 90.

- ^ "Calendario-Conversatorio-RD – Jornada Centenaria Ricardo E. Alegría Gallardo". centenarioricardoalegria.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2022. Retrieved 2022-11-05.

- ^ Sarah Cline, “Guadalupe and the Castas: The Power of a Singular Colonial Mexican Painting.” Mexican Studies/Esudios Mexicanos Vol. 31, Issue 2, Summer 2015, pages 218-46.

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 99.

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 95.

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 112.

- ^ García Sáiz & Jiménez Villalba 2009, p. 91.

- ^ "Vasija Nazca". Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte.

- García Sáiz, Mª Concepción; Jiménez Villalba, Félix (2009). "Museo de América, mucho más que un museo" (PDF). Artigrama. 24 (24). Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza: 83–118. doi:10.26754/ojs_artigrama/artigrama.2009247698. ISSN 0213-1498. S2CID 257308144.

- Krizmanics, Georg T. A. (2018). "El Museo de América de Madrid: ¿un instrumento para la política exterior española?". A Contracorriente. 15 (2): 39–61.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch![Luis de Mena, Casta painting with the Virgin of Guadalupe, 1750[7]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/29/Casta_Painting_by_Luis_de_Mena.jpg/250px-Casta_Painting_by_Luis_de_Mena.jpg)

![Helmet and collar made by the Tlingit people (late 18th century).[8]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ab/Casco_y_collera_de_lobo_tlingit_%28M._Am%C3%A9rica%2C_Madrid%29_02.jpg/250px-Casco_y_collera_de_lobo_tlingit_%28M._Am%C3%A9rica%2C_Madrid%29_02.jpg)

![Statuette of a Quimbaya cacique [es] (200–1000 AD)[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a6/Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica_Quimbaya_treasure_02.jpg/250px-Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica_Quimbaya_treasure_02.jpg)

![View of Seville, attributed to Alonso Sánchez Coello (late 16th century)[10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f6/La_sevilla_del_sigloXVI.jpg/500px-La_sevilla_del_sigloXVI.jpg)

![Maya Stele of Madrid [es] (600–900 AD)[11]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b9/Estela_%2847702715951%29.jpg/250px-Estela_%2847702715951%29.jpg)

![Nazca pot (1–600 AD)[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/Vasija_que_representa_a_un_pescador_tocando_la_flauta._Cultura_Nazca_%28100_a._C.-700_d._C.%29._Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica.jpg/250px-Vasija_que_representa_a_un_pescador_tocando_la_flauta._Cultura_Nazca_%28100_a._C.-700_d._C.%29._Museo_de_Am%C3%A9rica.jpg)