Mutilated victory

Mutilated victory (Italian: vittoria mutilata) is a term coined by Gabriele D'Annunzio at the end of World War I, used by a part of Italian nationalists to denounce the partial infringement (and request the full application) of the 1915 pact of London concerning territorial rewards in favour of the Kingdom of Italy.

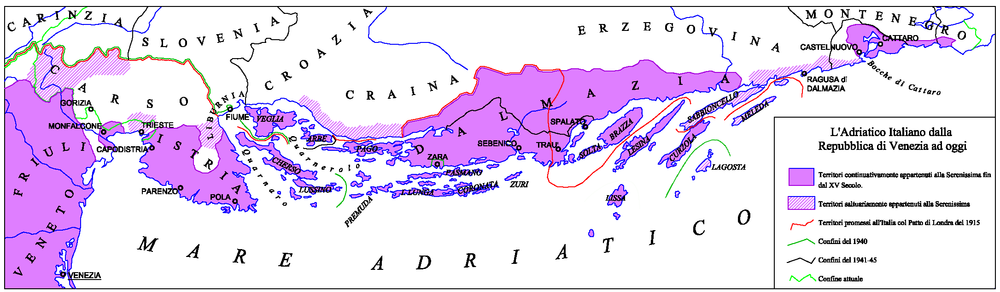

As a condition for entering the war against Austria-Hungary and Germany, Italy was promised, in the treaty of London signed in 1915 with the powers of the Triple Entente, recognition of control over Southern Tyrol, the Austrian Littoral and Dalmatia. These lands were inhabited by Italians which had not become part of the Kingdom upon Italian unification in the late 19th century, Austrian Germans (Tyroleans) and Slavs (Slovenes and Croats). Additionally, Italy was assured ownership of the Dodecanese, possessions in Albania, and a sphere of influence around the Turkish city of Antalya, alongside a possible enlargement of her colonial presence in Africa.

At the end of the war, despite the initial intention of the United Kingdom and France to remain faithful to the pact, objections by the United States, eventually supported by the British and the French, and in particular conflict over the concept of self-determination spelled out by President Wilson in his Fourteen Points, led to the partial disapplication of the agreement and to the retraction of some promises recognized at the onset of the conflict. Italy completed the national unification of the country by annexing the provinces of Trento and Trieste, and also gained South Tyrol, Istria and some colonial compensations, but was not awarded Dalmatia, with the exception of the city of Zara. Fiume, a city with a sizeable Italian population, although not included in the Pact of London, was occupied for a year by volunteers led by D'Annunzio, leading to an international crisis.

Together with the economical cost of mobilization and the social turmoil ensuing from the end of the war, the partial infringement of the treaty is generally believed to have fuelled the consolidation of Italian irredentism and Italian nationalism, and became a focal point in the propaganda, among others, of the National Fascist Party, which sought to expand the borders of the Italian state.

Description

[edit]

Italy joined World War I in 1915 on the side of the Allies, after negotiating the secret Treaty of London with the Triple Entente (Britain, France, and Russia). According to the secret pacts of London, the following territories were promised to Italy in case of victory: Trentino and South Tyrol, the Austrian Littoral (Trieste, Gorizia and Gradisca, and Istria), territories in Dalmatia, possessions in Albania (Vlora and Saseno), and compensations in case of a colonial partition of the Central Powers' empires. The content of the pact of London was made public in 1917 by the Russians, following their withdrawal from the War after the communist revolution, in order to criticize the "old diplomacy" of the capitalist European powers. While France and Britain remained bound by the treaty of London, the US president Woodrow Wilson (who joined the Allies in 1917) opposed it and presented on January 8, 1918 Fourteen Points to redraw the map of Europe on the basis of nationality and ethnicity. During the decisive Italian offensive, the nationalist poet Gabriele D'Annunzio coined the term mutilated victory by publishing an article in the Corriere della Sera dated October 24, 1918 and titled "Our victory will not be mutilated".[1]

Italy's prime minister Vittorio Orlando, one of the Big Four of World War I, and his foreign minister Sidney Sonnino, an Anglican of British origins, arrived at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919 in order to secure most of the London pacts. Considerable results were achieved with the treaties and agreements signed in 1919 and 1920. Most importantly, Trent-South Tyrol and the Austrian Littoral (Trieste, Gorizia and Gradisca, and Istria) became part of the Italian regions of Trentino-Alto Adige and Friuli-Venezia Giulia. The colonial compensations obtained by Italy were: the recognition and enlargement of the Italian Islands of the Aegean; the enlargement of the Italian possessions in Libya and in the Horn of Africa; and the establishment of an Italian sphere of influence over the Ottoman area of Antalya, later abandoned with the independence of Turkey. Italy also received the province of Zadar with some islands in Dalmatia and set up an Italian protectorate over Albania with the occupation of Vlora, which lasted until 1920 when domestic opposition within the Italian Armed Forces and the Vlora war led Italy to voluntarily abandon Albania; with the treaty of Tirana, Italy retained the island of Saseno and recognition of Albania as being within its sphere of influence (which was confirmed by the League of Nations in 1921). Finally, the disintegration of its two main rival powers (Austria-Hungary in Europe and the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean) and the entrance in the League of Nations' security council as a permanent member, cemented Italy's status as a great power.

Therefore, most of the criticism directed against the Allies and the government focused on Dalmatia and the city of Fiume (which was later occupied by a contingent led by Gabriele D'Annunzio). A more substantial transfer of Dalmatian territories to Italy (favoured by Sonnino) was complicated to achieve because of its Slavic population, whereas Fiume was ethnically an Italian city (and as such proposed by Orlando as an alternative), but not included in the Pact of London. Wilson vetoed these proposals on the ground that already many Germanophones and Slavs were to be placed under Italian administration. This led Orlando and Sonnino to temporarily abandon the conference in protest. Orlando had refused to see the outcome of the war as a mutilated victory and once replied to calls for greater expansion that "Italy today is a great state... on par with the great historic and contemporary states. This is, for me, our main and principal expansion." But the disgruntled climate ultimately forced Orlando to resign, and the treaties he had negotiated were signed by his successors Francesco Saverio Nitti and Giovanni Giolitti.[2]

From a contemporary historical point of view, it has sometimes been observed how much of Benito Mussolini's foreign policy was presented as an attempt to amend the injustices lamented as stemming from the mutilated victory: Fiume was taken in 1924, Albania was turned into a client state under Zog I and merged into the Kingdom in 1939, and Dalmatia was annexed during the occupation of Yugoslavia—events that have been sporadically accused of prolonging Italy's participation in World War II. Some historians have at times seen the actions carried by the Fascist government on the subject as part of a larger imperialist project that brought Italy to descend into foreign affairs, by intervening in Spain, conquering Ethiopia, and occupying southern France and Tunisia. For historian Gaetano Salvemini "Fascism originated, grew, triumphed, and ultimately died, on the myth of mutilated victory".[3] Conversely, attempts to include in the Italian nation state the detached lands populated by Italophones have also been lauded and supported, with subjects failing to recognize said urgency being decried by poet Gabriele D’Annunzio as "insane and vile".[4]

Notwithstanding the political characterisations of the Interwar period, the final settlement of peace after the end of World War II, which had deprived Italy of all of the lands to the east of the Adriatic Sea (except for the city of Trieste), proved to be unpopular among the Italian opinion and object of harsh criticism, being described by President Luigi Einaudi as leading to a condition of "painfully mutilated" national unity.[5]

Italy and the Triple Alliance

[edit]Angered by the French seizure of Tunisia, in which Italy had extensive economic interests and had viewed as a possible area for colonial annexation, in 1882, Italy joined the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria as a means of defending against further French aggression and gaining diplomatic backing for coming disputes.[6] The alliance, however, proved troublesome. Italy and Austria-Hungary had been rivals for many years; the latter had, for years, held northeastern Italy, opposed Italian unification, and it still held Trieste and Istria, Zara and the coast of Dalmatia, the primary targets of the Italian irredentist movement.

As such, in the years before 1914, Italy engaged in diplomatic maneuvers to ally itself with the United Kingdom and France. In 1902, Italy concluded a secret treaty with Britain in which Italy abandoned the Triple Alliance, with the stipulation that it be given the territories currently controlled by Austria.

Treaty of London (1915)

[edit]After World War I erupted, the pressure by both sides for Italy to enter the war increased. On April 26, 1915, the Triple Entente and Italy signed a secret agreement, called the Treaty of London, that stipulated the terms of Italy’s participation in World War I against the Germany-Austrian Alliance. If Italy declared war on Germany and the Entente emerged victorious, Italy would be awarded territories of the House of Habsburg in the Southern Alps and in the Balkans, specifically the regions of Trentino and the South Tyrol (up to the northern limit of the Brenner Pass), the Friuli-Julian area, Trieste and the surrounding area, Istria, and the North of the Dalmatian Cost including the city of Šibenik. Other possible territories included in the treaty were the city of Vlorë in Albania, some part on the south Anatolian coast, as well as a share of the German colonial empire.

These demands were outlined by the Italian Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino to secure a strong Italian presence in the Mediterranean. The acquisition of the area surrounding the Adriatic, especially the port city of Trieste, would strengthen Italian naval presence and keep pace with possible postwar territorial gains in the area by the other members of the Entente. The demands for lands carved from the Ottoman Empire and the African colonies were motivated by national ambition.

Sonnino however delayed a declaration of war against Germany although Italy had declared war on Austria-Hungary. By May 1915, the Italian push towards Ljubljana reached a stalemate with Austrian forces in the Alps while Britain, France and Germany were embroiled in a stalemate of their own on the Western Front. The outcome of the war was not yet clear, and Sonnino stood by a position of neutrality with Germany. That would soften as Sonnino realized Italy’s army was in no position to carry out a protracted war, and pressure from within Italy demanded solidarity with the Entente. The Italian government declared war on Germany on 28 August 1916.

Wilson's opposition

[edit]In January 1917, British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour wrote a letter to American President Woodrow Wilson expressing his disapproval of the promise to give Italy the Adriatic territories. In a later trip to the United States in May to speak with American diplomat Edward M. House about the pact, Balfour made it clear that Britain had no particular ill will against Austria-Hungary and that the planned transfer of the Slavic lands to Italy would only create more problems. While American-Italian diplomatic dialogue regarding the claims did not take place prior to the Peace Conference, Wilson’s own stance on the matter was clear in his Fourteen Points, which urged for the Italian border with Austria to be redrawn along "clearly recognizable lines of nationality". His first point urged for no international agreements to be negotiated in secret so he refused to recognise the arrangements made under the pact. Sonnino's plans for securing the Adriatic were ignored, as were the imperial aims of Italy, and concessions were made in the form of postwar American economic aid.[7]

Aftermath

[edit]The cause of mutilated victory was embraced by many Italians, particularly in the irredentist, monarchical, militaristic factions. The poet Gabriele D'Annunzio criticized in print and in speeches the failures of Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando at the proceedings in Versailles, particularly in his attempts to acquire the city of Fiume (Croatian: Rijeka), which, notwithstanding the fact that its inhabitants were more than 90% ethnic Italians, was supposed to be ceded by Austria to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. On September 12, 1919, D’Annunzio took matters into his own hands and led a militia of 2,600 men against a mixed force of Allied soldiers to occupy the city. In Fiume, the victors established the Italian Regency of Carnaro, an unrecognized state based on the Charter of Carnaro.

While the regime would be short-lived, its effect on the people and politics of the Kingdom of Italy would leave their mark on the following decades of Italian history. Benito Mussolini was resolute to endorse the safeguard of national unity during the period of the creation of the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento, the precursor of the National Fascist Party. Mussolini, an interventionist in World War I, attributed Italy’s great price of over 1.2 million casualties and 148 billion lire of expenditure to the weakness of the national government and to the disloyal attitude of the country’s former allies.[8]

See also

[edit]- Italian entry into World War I

- Italian front (World War I)

- Military history of Italy during World War I

- Stab in the back myth

- Pyrrhic victory

References

[edit]- ^ Cfr. Gabriele D'Annunzio, in an editorial in Corriere della Sera, October 24, 1918, Vittoria nostra, non sarai mutilata ('Our victory will not be mutilated')

- ^ Atti Parlamentari, Camera dei Deputati, Discussioni.

- ^ [...] Il movimento fascista sorse, crebbe, trionfò, e alla fine si stroncò, sul mito della "vittoria mutilata" [...], Gaetano Salvemini, Scritti sul Fascismo, vol. 3, Feltrinelli, 1974, p. 417.

- ^ [...] Nel mondo folle e vile, Fiume è oggi il segno della libertà; nel mondo folle e vile vi è una sola verità: e questa è Fiume; vi è un solo amore: e questo è Fiume! [...], Gabriele D’Annunzio. Speech in Fiume, on fiume.vittoriale.it. Published September 12, 1919. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ [...] Dopo aver salvata, pur nelle diversità regionali e locali e pur dolorosamente mutilata, la indistruttibile unità nazionale dalle Alpi alla Sicilia [...], Luigi Einaudi. Presidential inauguration speech, on presidenti.quirinale.it. Published May 12, 1948. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ Lowe, C.J. (2002). Italian Foreign Policy 1870-1940. Routledge.

- ^ Burgwyn, H. James. (1993). The Legend of the Mutilated Victory. Greenwood Press.

- ^ Mack Smith, Denis (1997). Modern Italy. The University of Michigan Press.

Bibliography

[edit]- Burgwyn, H. James. The Legend of the Mutilated Victory (Greenwood Press, 1993).

- Lowe, C.J. Italian Foreign Policy 1870-1940 (2002).

- Mack Smith, Denis. Modern Italy (University of Michigan Press, 1997).

- Wilcox, Vanda. "From heroic defeat to mutilated victory: The myth of Caporetto in Fascist Italy". in Jenny Macleod, ed. Defeat and Memory (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008) pp. 46–61.

External links

[edit]- Vittoria mutilata on Fondazione Feltrinelli, Erica Grossi.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch