Mysterioso Pizzicato

Mysterioso Pizzicato, also known as The Villain or The Villain's Theme, is a piece of music whose earliest known publication was in 1914, when it appeared in an early collection of incidental photoplay music aimed at accompanists for silent films. The main motif, with minor variations, has become a well-known and widely used device (or "cliche"),[1] incorporated into various other musical works, and the scores of films, TV programmes and video games, as well as unnotated indications in film scripts.

Both a character theme (the "traditional 'bad-guy' cue"[2]) and situation theme,[3] it is used to herald foreboding or disaster and to represent villainy, sneakiness, or stealth. A version of this theme is contrasted with themes such as the hero's (ⓘ).[4]

Various versions have in common staccato notes, or a note-rest pattern, in imitation of the short sustain of string pizzicato. They share a minor key, considered more sad or ominous. They begin with a staccato ascending arpeggio, reach a tremolo or trill on the minor submediant (♭6), and then descend through faster step-wise melodic motion.

History

[edit]

The tune appeared as no. 89 in The Remick Folio of Moving Picture Music, vol. I, compiled and edited by the Danish-American composer J. Bodewalt Lampe and published on March 24, 1914 by Jerome H. Remick & Co., New York and Detroit.[7][8][9] It is unclear whether Lampe himself was the composer or transcriber of the piece. It also bears a resemblance to part of John Stepan Zamecnik's 1913 composition Mysterious – Burglar Music 1, which appeared in Sam Fox Moving Picture Music volume 1,[10] a widely distributed collection of silent film music. It has been described as reflecting "the tradition of stealthy tremolos that marked the entrance of villains in 19th century stage melodrama".[8] By 1917 the idea of villain's motifs in general, or variants of the specific motif, was established well enough for an author to warn against the "monotonous and wearisome" overuse of the motif "whenever [the villain] is seen".[11] Other motifs used to indicate villainy or danger include the second section of "Hearts and Flowers" (1893).[12] In 1916 a similarly titled song called "Pizzicato Misterioso (For Burglary and Stealth)" by Adolf Minot also composed for film, but bears no resemblance to this song.[13]

Uses

[edit]

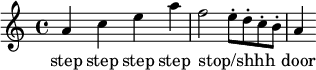

Mysterioso Pizzicato has seen "hundreds of tongue-in-cheek uses" in features and cartoons.[14] The melody appears prominently in the first Disney Silly Symphonies cartoon, The Skeleton Dance (1929) with music composed by Carl Stalling.[15] Irving Berlin used a version of it in his 1921 Music Box Revue show to accompany the entrance of a band of burglars.[5] In the 1931 Van Beuren Studios animated short Making 'Em Move it is first used to produce a 'false sense of foreboding' as a curious visitor enters the animation factory, and then again to accompany the villain in a cartoon-within-a-cartoon, and at both points the animation is Mickey Moused to synchronise the character's movements with the music.[2] The entrance is:

The motif is referenced in a number of Max Steiner's film scores,[14] including The Adventures of Mark Twain (1944) in which it forms part of "the low instrumental buffoonery illustrating an afternoon of frog-catching".[16]

One use in popular music was by Frank Zappa, who incorporated the riff into live performances of his song "Zomby Woof".[1][17] It is also used as an opening riff for Shonen Knife's song "Devil House" on their albums Pretty Little Baka Guy and Let's Knife; Avenged Sevenfold's song "Reminissions" on their album Waking the Fallen, The Sonics' 1965 song "Strychnine"; and on Johnny Sayles' 1965 song "My Love's a Monster". It is also the basis for the instrumental "Scrooge," included in The Ventures' Christmas Album, in an arrangement credited to band members Don Wilson, Bob Bogle, Nokie Edwards, and Mel Taylor. The motif also appears in Supplique pour être enterré à la plage de Sète by Georges Brassens (1966).[citation needed]

In the graphic adventure game King's Quest VI: Heir Today, Gone Tomorrow, the tune is used as the background music for one area of the Isle of Wonder, specifically the tune to the character Bookworm.[18] It is also used as boss encounter music in the Rareware video game Wizards and Warriors.

Anna Russell, in her traversal of Wagner's Ring Cycle, uses the cue to represent the curse placed by Alberich on the magic ring, before realizing her mistake and saying "That's the wrong curse, isn't it."

In the Apple IIGS home computer game, The Three Stooges, the tune is used as I. Fleecum's theme. It plays when he is about to foreclose the orphanage, when the Stooges have selected a visit with I. Fleecum, or when the game ends with less than $5,000 (Ma loses the orphanage). After the song ends, the player would hear I. Fleecum laugh. The tune was also used in the Nintendo Entertainment System port.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Hand, Richard J. (2013) "Zappa and Horror: Screamin' at the monster" in Paul Carr (ed), Frank Zappa and the And, p.25. Farmham, Ashgate. ISBN 9781409473466.

- ^ a b Goldmark, D. (2011). "Sounds Funny/Funny Sounds". In D. Goldmark and C. Keil (eds). Funny Pictures: Animation and comedy in studio-era Hollywood pp 260–261. Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California. ISBN 9780520950122.

- ^ Randall, Charles H. and Bushnel, Joan LeGro (1986). Hisses, Boos & Cheers, Or, A Practical Guide to the Planning, Producing, and Performing of Melodrama, p.61. Dramatic. ISBN 9780871294210.

- ^ Braun, Wilbur (1989). Foiled Again: Two Musical Melodramas, p.4. Samuel French. ISBN 9780573682001.

- ^ a b c Magee, Jeffrey (2012). Irving Berlin's American Musical Theater. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-19539826-7.

- ^ Goldmark, Daniel (2013). Sounds for the Silents: Photoplay Music from the Days of Early Cinema. Courier. p. 38. ISBN 9780486492865.

- ^ Fuld, James J. (2000) The Book of World-Famous Music, 5th ed. Dover Publications. p. 385

- ^ a b Program notes, From Nineteenth-Century Stage Drama to Twenty-First-Century Film Scoring: Musicodramatic Practice and Knowledge Organization (2012). Society for American Music and the California State University, Long Beach, College of the Arts

- ^ Magee (2012), p.321n31.

- ^ Sam Fox Moving Picture Music (Zamecnik, John Stepan): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project, Vol. II, p.16. Accessed September 28, 2015.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Joseph (1918). "Music in Motion Pictures", Pacific Coast Musical Review, Volume 33, No.14, p.11. Alfred Metzger. [ISBN unspecified].

- ^ Holland, Nola Nolen (2013). Music Fundamentals for Dance, p.13. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736096522.

- ^ Berg, S. M. (1916). "Pizzicato Misterioso (For Burglary and Stealth)". Berg's Incidental Series, Number 30: Plate 1243.

- ^ a b Rosar, William H. (Fall 1983). "Music for the Monsters". The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress: 402. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ Bohn, James (2017). Music in Disney's Animated Features: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to The Jungle Book. USA: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781496812155. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Whitaker, Bill. "Max Steiner (1888-1971) The Adventures of Mark Twain Musical Americana to the Max". Naxos. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ 'Zomby Woof', Cheap Thrills on YouTube. About 4:33.

- ^ King's Quest VI OST T15 - The Bookworm on YouTube

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch