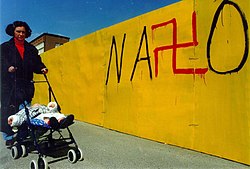

NATO bombing of Yugoslavia

| NATO bombing of Yugoslavia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Kosovo War | |||||||||

The Yugoslav city of Novi Sad on fire in 1999 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

NATO:

| |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

2013 Serbian MOD estimate:

304 soldiers and policemen[24] Material losses: NATO estimate:[25][26]

| |||||||||

| Human Rights Watch estimate: 489–528 civilians killed (60% of whom were in Kosovo)[27] Yugoslav estimate: 1,200–2,000 civilians killed[27] and about 6,000 civilians wounded[28] FHP: | |||||||||

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Personal 40th and 42nd Governor of Arkansas 42nd President of the United States Tenure Appointments Presidential campaigns

| ||

| ||

|---|---|---|

| President of Serbia and Yugoslavia

Elections Family

| ||

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) carried out an aerial bombing campaign against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia during the Kosovo War. The air strikes lasted from 24 March 1999 to 10 June 1999. The bombings continued until an agreement was reached that led to the withdrawal of the Yugoslav Army from Kosovo, and the establishment of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo, a UN peacekeeping mission in Kosovo. The official NATO operation code name was Operation Allied Force (Serbian: Савезничка сила / Saveznička sila) whereas the United States called it Operation Noble Anvil (Serbian: Племенити наковањ / Plemeniti nakovanj);[29] in Yugoslavia, the operation was incorrectly called Merciful Angel (Serbian: Милосрдни анђео / Milosrdni anđeo), possibly as a result of a misunderstanding or mistranslation.[30]

NATO's intervention was prompted by Yugoslavia's bloodshed and ethnic cleansing of Kosovar Albanians, which drove the Albanians into neighbouring countries and had the potential to destabilize the region. Yugoslavia's actions had already provoked condemnation by international organisations and agencies such as the UN, NATO, and various INGOs.[31][32] Yugoslavia's refusal to sign the Rambouillet Accords was initially offered as justification for NATO's use of force.[33] Because Russia and China could use their veto within the Security Council to not authorize an external intervention,[34] NATO launched its campaign without the UN's approval, stating that it was inter alia a humanitarian intervention.[35] The UN Charter prohibits the use of force except in the case of a decision by the Security Council under Article 42, under Article 51 or under Article 53.[36] Three days after the commencement of hostilities, on 26 March 1999, the Security Council rejected the demand of Russia, Belarus and India for the cessation of the use of force against Yugoslavia.[37]

By the end of the war, the Yugoslavs had killed 1,500[38] to 2,131 combatants.[39] 10,317 civilians were killed or missing, with 85% of those being Kosovar Albanian and some 848,000 were expelled from Kosovo.[40] The NATO bombing killed about 1,000 members of the Yugoslav security forces in addition to between 489 and 528 civilians. It destroyed or damaged bridges, industrial plants, hospitals, schools, cultural monuments, and private businesses, as well as barracks and military installations. In total, between 9 and 11 tonnes of depleted uranium was dropped across all of Yugoslavia.[41] In the days after the Yugoslav army withdrew, over 164,000 Serbs and 24,000 Roma left Kosovo. Many of the remaining non-Albanian civilians (as well as Albanians perceived as collaborators) were victims of abuse which included beatings, abductions, and murders.[42][43][44][45][46] After Kosovo and other Yugoslav Wars, Serbia became home to the highest number of refugees and internally displaced persons (including Kosovo Serbs) in Europe.[47][48][49]

The bombing was NATO's second major combat operation, following the 1995 bombing campaign in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was the first time that NATO had used military force without the expressed endorsement of the UN Security Council and thus, international legal approval,[50] which triggered debates over the legitimacy of the intervention.

Background

A NATO-facilitated ceasefire between the KLA and Yugoslav forces was signed on 15 October 1998, but both sides broke it two months later and fighting resumed. UN Security Council resolution 1160, resolution 1199 and resolution 1203 had been disregarded. When the killing of 45 Kosovar Albanians in the Račak massacre was reported in January 1999, NATO decided that the conflict could only be settled by introducing a military peacekeeping force to forcibly restrain the two sides.[51] Yugoslavia refused to sign the Rambouillet Accords, which among other things called for 30,000 NATO peacekeeping troops in Kosovo; an unhindered right of passage for NATO troops on Yugoslav territory; immunity for NATO and its agents to Yugoslav law; and the right to use local roads, ports, railways, and airports without payment and requisition public facilities for its use free of cost.[52][33] NATO then prepared to install the peacekeepers by force, using this refusal to justify the bombings.[citation needed]

In its Statement Issued at the Extraordinary Ministerial Meeting of the North Atlantic Council held at NATO Headquarters, Brussels, on 12th April 1999 three weeks after the start of hostilities on 23 March 1999, the collective said that "The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) has repeatedly violated United Nations Security Council resolutions. The unrestrained assault by Yugoslav military, police and paramilitary forces, under the direction of President Milosevic, on Kosovar civilians has created a massive humanitarian catastrophe which also threatens to destabilise the surrounding region. Hundreds of thousands of people have been expelled ruthlessly from Kosovo by the FRY authorities. We condemn these appalling violations of human rights and the indiscriminate use of force by the Yugoslav government. These extreme and criminally irresponsible policies, which cannot be defended on any grounds, have made necessary and justify the military action by NATO."[35]

Goals

NATO's objectives in the Kosovo conflict were stated at the North Atlantic Council meeting held at NATO headquarters in Brussels on 12 April 1999:[35]

- An end to all military action and the immediate termination of violence and repressive activities by the Milošević government;

- Withdrawal of all military, police and paramilitary forces from Kosovo;

- Stationing of UN peacekeeping presence in Kosovo;

- Unconditional and safe return of all refugees and displaced persons;

- Establishment of a political framework agreement for Kosovo based on Rambouillet Accords, in conformity with international law and the Charter of the United Nations.

Strategy

Operation Allied Force predominantly used a large-scale air campaign to destroy Yugoslav military infrastructure from high altitudes. After the third day of aerial bombing, NATO had destroyed almost all of its strategic military targets in Yugoslavia. Despite this, the Yugoslav army continued to function and to attack Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) insurgents inside Kosovo, mostly in the regions of Northern and Southwest Kosovo. NATO bombed strategic economic and societal targets, such as bridges, military facilities, official government facilities, and factories, using long-range cruise missiles to hit heavily defended targets, such as strategic installations in Belgrade and Pristina. The NATO air forces also targeted infrastructure, such as power plants (using the BLU-114/B "Soft-Bomb"), water-processing plants and the state-owned broadcaster. The Dutch foreign minister Jozias van Aartsen said that the strikes on Yugoslavia should be such as to weaken their military capabilities and prevent further humanitarian atrocities.[53]

Due to restrictive media laws, media in Yugoslavia carried little coverage of what its forces were doing in Kosovo, or of other countries' attitudes to the humanitarian crisis; so, few members of the public expected bombing, instead thinking that a diplomatic deal would be made.[54]

While according to Noel Malcolm: "During the first few days of the air-strike campaign, while NATO confined itself to the use of cruise missiles and high-altitude bombing, the Serbian forces inside Kosovo embarked on a massive campaign of destruction, burning down houses and using tanks and artillery to reduce entire villages to rubble."[55]

Arguments for strategic air power

According to John Keegan, the capitulation of Yugoslavia in the Kosovo War marked a turning point in the history of warfare. It "proved that a war can be won by air power alone". Diplomacy had failed before the war, and the deployment of a large NATO ground force was still weeks away when Slobodan Milošević agreed to a peace deal.[56]

As for why air power should have been capable of acting alone, it has been argued by military analysts that there are several factors required. These normally come together only rarely, but all occurred during the Kosovo War:[57]

- Bombardment needs to be capable of causing destruction while minimising casualties. This causes pressure within the population to end hostilities rather than to prolong them. The exercise of precision air power in the Kosovo War is said by analysts to have provided this.

- The government must be susceptible to pressure from within the population. As was demonstrated by the overthrow of Milošević a year later, the Yugoslav government was only weakly authoritarian and depended upon support from within the country.

- There must be a disparity of military capabilities such that the opponent is unable to inhibit the exercise of air superiority over its territory. Serbia, a relatively small impoverished Balkan state, faced a much more powerful NATO coalition including the United Kingdom and the United States.

- Carl von Clausewitz once called the "essential mass of the enemy" his "centre of gravity". Should the center of gravity be destroyed, a major factor in Yugoslav will to resist would be broken or removed. In Milošević's case, the centre of gravity was his hold on power. He manipulated hyperinflation, sanctions and restrictions in supply and demand to allow powerful business interests within Serbia to profit and they responded by maintaining him in power. The damage to the economy, which squeezed it to a point where there was little profit to be made, threatened to undermine their support for Milošević if the air campaign continued, whilst causing costly infrastructure damage.[58]

Arguments against strategic air power

- Diplomacy:

- According to British Lieutenant-General Mike Jackson, Russia's decision on 3 June 1999 to back the West and to urge Milošević to surrender was the single event that had "the greatest significance in ending the war". The Yugoslav capitulation came the same day.[59] Russia relied on Western economic aid at the time, which made it vulnerable to pressure from NATO to withdraw support for Milošević.[60]

- Milošević's indictment by the UN as a war criminal (on 24 May 1999), even if it did not influence him personally, made the likelihood of Russia resuming diplomatic support less likely.[61]

- The Rambouillet Agreement of 18 March 1999, had Yugoslavia agreed to it, would have given NATO forces the right of transit, bivouac, manoeuvre, billet, and use across Serbia. By the time Milošević capitulated, NATO forces were to have access only to Kosovo proper.[62]

- The international civil presence in the province was to be under UN control which allowed for a Russian veto should Serb interests be threatened.[62]

- Concurrent ground operations – The KLA undertook operations in Kosovo itself and had some successes against Serb forces. The Yugoslav army abandoned a border post opposite Morinë near the Yugoslav army outpost at Košare in the north west of the province. The Yugoslav army outpost at Košare had remained in Yugoslav hands throughout the war: this allowed for a supply line to be set up into the province and the subsequent taking of territory in the Junik area. The KLA also penetrated a few miles into the south-western Mount Paštrik area. But most of the province remained under Serb control.[63]

- Potential ground attack – General Wesley Clark, Supreme Allied Commander Europe, was "convinced" that planning and preparations for ground intervention "in particular, pushed Milošević to concede".[64] The Yugoslav capitulation occurred on the same day that US President Bill Clinton held a widely publicised meeting with his four service chiefs to discuss options for a ground-force deployment in case the air war failed.[65] However, France and Germany vigorously opposed a ground offensive, and had done so for some weeks, since April 1999. French estimates suggested that an invasion would need an army of 500,000 to achieve success. This left NATO, particularly the United States, with a clear view that a land operation had no support. With this in mind, the US reaffirmed its faith in the air campaign.[66] The reluctance of NATO to use ground forces cast serious doubt on the idea that Milošević capitulated out of fear of a land invasion.[67]

Operation

On 20 March 1999, OSCE Kosovo Verification Mission monitors withdrew from Kosovo citing a "steady deterioration in the security situation",[68][69] and on 23 March 1999 Richard Holbrooke returned to Brussels and announced that peace talks had failed.[70] Hours before the announcement, Yugoslavia announced on national television it had declared a state of emergency citing an "imminent threat of war ... against Yugoslavia by Nato" and began a huge mobilisation of troops and resources.[70][71] On 23 March 1999 at 22:17 UTC the Secretary General of NATO, Javier Solana, announced he had directed the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR), General Wesley Clark, to "initiate air operations in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia."[71][72]

NATO operations

The campaign involved 1,000 aircraft operating from air bases in Italy and Germany, and the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt sailing in the Adriatic Sea.[73] During the ten weeks of the conflict, NATO aircraft flew over 38,000 combat missions, with a little over 10,000 of those being airstrike missions.[74]

On 24 March at 19:00 UTC NATO started the bombing campaign against Yugoslavia.[75][76] F/A-18 Hornets of the Spanish Air Force were the first NATO planes to bomb Belgrade and perform SEAD operations.[77] A total of 202 BGM-109 Tomahawk cruise missiles were fired from ships and submarines in the Adriatic,[78] with missiles being launched from the Ticonderoga-class cruiser USS Philippine Sea (CG-58), Arleigh Burke-class destroyer USS Gonzalez DDG-61, Los Angeles-class submarine's USS Albuquerque (SSN-706) & USS Miami (SSN-755) and the Royal Navy Swiftsure-class submarine HMS Splendid (S106).[73]

In addition to fixed-wing air power, one battalion of Apache helicopters from the US Army's 11th Aviation Regiment was deployed to help combat missions.[79] The regiment was augmented by pilots from Fort Bragg's 82nd Airborne Attack Helicopter Battalion.[80] The battalion secured AH-64 Apache attack helicopter refueling sites, and a small team forward deployed to the Albania – Kosovo border to identify targets for NATO air strikes.[81]

The campaign was initially designed to destroy Yugoslav air defences and high-value military targets.[82] NATO military operations increasingly attacked Yugoslav units on the ground, as well as continuing the strategic bombardment. Montenegro was bombed several times, and NATO refused to prop up the precarious position of its anti-Milošević leader, Milo Đukanović. "Dual-use" targets, used by civilians and military, were attacked, including bridges across the Danube, factories, power stations, telecommunications facilities, the headquarters of Yugoslav Leftists, a political party led by Milošević's wife, and the Avala TV Tower. Some protested that these actions were violations of international law and the Geneva Conventions. NATO argued these facilities were potentially useful to the Yugoslav military and thus their bombing was justified.[83]

On 12 April, NATO airstrikes struck a railway bridge in Grdelica, hitting a civilian passenger train and killing twenty people.[84] Showing video footage, General Wesley Clark later apologized and stated that the train had been traveling too fast and the bomb was too close to the target for it to divert in time. The German daily Frankfurter Rundschau reported in January 2000 that the NATO video had been shown at three times its real speed, giving a misleading impression of the train's speed.[85]

On 14 April, NATO planes bombed ethnic Albanians near Koriša who had been used by Yugoslav forces as human shields.[86][87] Yugoslav troops took TV crews to the scene shortly after the bombing.[88] The Yugoslav government insisted that NATO had targeted civilians.[89][90][91]

On 23 April, NATO bombed the Radio Television of Serbia headquarters killing sixteen civilian employees. This was labeled as a war crime by Amnesty International.[92] NATO claimed that the bombing was justified because the station operated as a propaganda tool for the Milošević regime.[83]

On 7 May, the US bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, killing three Chinese journalists and injuring at least 20.[93] The US defence secretary explained the cause of the error as "because the bombing instructions were based on an outdated map", but the Chinese government did not accept this explanation. The Chinese government issued a statement on the day of the bombing, stating that it was a "barbarian act".[94] The target had been selected by the Central Intelligence Agency outside the normal NATO targeting regime. The US president Bill Clinton apologised for the bombing, saying it was an accident.[95][96][97] The US gave China financial compensation.[98][99] The bombing strained relations between the People's Republic of China and NATO, provoking angry demonstrations outside Western embassies in Beijing.[100] The victims were Xu Xinghu, his wife Zhu Ying, and Shao Yunhuan. An October 1999 investigation by The Observer and Politiken argued that the bombing had actually been deliberate as the Embassy was being used to transmit Yugoslav army communications, something that NATO, the UK and the US emphatically denied.[101][102][103] In April 2000, The New York Times published its own investigation, claiming to have found "no evidence that the bombing of the embassy had been a deliberate act."[104]

NATO command organisation

Solana directed Clark to "initiate air operations in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia". Clark then delegated responsibility for the conduct of Operation Allied Force to the Commander-in-Chief of Allied Forces Southern Europe, who in turn delegated control to the Commander of Allied Air Forces Southern Europe, Lieutenant-General Michael C. Short, USAF.[105] Operationally, the day-to-day responsibility for executing missions was delegated to the Commander of the 5th Allied Tactical Air Force.[106]

Yugoslav operations

The Hague Tribunal ruled that over 700,000 Kosovo Albanians were forcibly displaced by Yugoslav forces into neighbouring Albania and Macedonia, with many thousands internally displaced within Kosovo.[107] By April, the United Nations reported 850,000 refugees had left Kosovo.[108] Another 230,000 were listed as internally displaced persons (IDPs): driven from their homes, but still inside Kosovo. German Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer and Defense Minister Rudolf Scharping claimed at the time that the refugee crisis was produced by a coordinated Yugoslav plan of ethnic cleansing codenamed "Operation Horseshoe". The existence and character of such a plan has been called into question.[109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116]

Serbian Television claimed that huge columns of refugees were fleeing Kosovo because of NATO's bombing, not Yugoslav military operations.[117][118] The Yugoslav side and its Western supporters claimed the refugee outflows were caused by a mass panic in the Kosovo Albanian population, and that the exodus was generated principally by fear of NATO bombs.

The United Nations and international human rights organisations were convinced the crisis resulted from a policy of ethnic cleansing. Many accounts from both Serbs and Albanians identified Yugoslav security forces and paramilitaries as the culprits, responsible for systematically emptying towns and villages of their Albanian inhabitants by forcing them to flee.[119][failed verification]

Atrocities against civilians in Kosovo were the basis of United Nations war crimes charges against Milošević and other officials responsible for directing the Kosovo conflict.

On 29 March 1999, to escape possible destruction, Jat Airways evacuated around 30 of its fleet of civilian aircraft from Belgrade to neighbouring countries for safekeeping.[120]

Air combat

An important portion of the war involved combat between the Yugoslav Air Force and the opposing air forces from NATO. United States Air Force F-15s and F-16s flying from Italian airforce bases attacked the defending Yugoslav fighters, mainly MiG-29s, which were severely outmatched by the modern and more advanced F-15 & F-16's due to having obsolete radar systems & missiles, and were in poor condition due to a lack of spare parts and maintenance.[citation needed] Other NATO forces also contributed to the air war.

Air combat incidents:

- During the night of 24/25 March 1999: Yugoslav Air Force scrambled five MiG-29s to counter the initial attacks. Two fighters that took off from Niš Airport were vectored to intercept targets over southern Serbia and Kosovo were dealt with by NATO fighters. The MiG-29 flown by Maj. Dragan Ilić was damaged; he landed with one engine out and the aircraft was later expended as a decoy. The second MiG, flown by Maj. Iljo Arizanov, was shot down by an USAF F-15C piloted by Lt. Col. Cesar Rodriguez. A pair from Batajnica Air Base (Maj. Nebojša Nikolić and Maj. Ljubiša Kulačin) were engaged by USAF Capt. Mike Shower who shot down Nikolić while Kulačin evaded several missiles fired at him, while fighting to bring his malfunctioning systems back to working order. Eventually realising that he could not do anything, and with Batajnica AB under attack, Kulačin diverted to Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport, hiding his aircraft under the tail of a parked airliner.[121] The fifth and last MiG-29 to get airborne that night was flown by Maj. Predrag Milutinović. Immediately after take-off his radar failed and electrical generator malfunctioned. Shortly after, he was warned of being acquired by fire control radar, but he eluded the opponent by several evasive manoeuvres. Attempting to evade further encounters, he approached Niš Airport, intending to land, but he was eventually shot down by a KLU F-16AM flown by Maj. Peter Tankink and forced to eject.[122][123]

- In the morning of 25 March, Maj. Slobodan Tešanović stalled his MiG-29 while landing on Ponikve Airbase after a re-basing flight. He ejected safely.[124][125]

- During the war Yugoslav strike aircraft J-22 Oraos and G-4 Super Galebs performed some 20–30 combat missions against the KLA in Kosovo at treetop level[126] causing some casualties. During one of those missions on 25 March 1999, Lt. Colonel Života Ðurić was killed when his J-22 Orao hit a hill in Kosovo. It was never firmly established whether an aircraft malfunction, pilot error or if enemy action (by KLA) was the cause (NATO never claimed they shot it down).[124]

- In the afternoon of 25 March 1999 two Yugoslav MiG-29s took off from Batajnica to chase a lone NATO aircraft flying in the direction of the Bosnian border. They crossed the border and were engaged by two US F-15s. Both MiGs were shot down by Captain Jeff Hwang.[127] One MiG pilot, Major Slobodan Perić, having evaded at least one missile before being hit ejected, was later smuggled back to Yugoslavia by the Republika Srpska police. The other pilot, Captain Zoran Radosavljević, did not eject and was killed.[128]

- On 27 March 1999, the 3rd Battalion of the 250th Missile Brigade, under the command of Colonel Zoltán Dani, equipped with the Isayev S-125 'Neva-M' (NATO designation SA-3 Goa), downed an American F-117 Nighthawk.[129][130] The pilot ejected and was rescued by search and rescue forces near Belgrade consisting of two Sikorsky MH-53 helicopters and a Sikorsky HH-60 Pave Hawk operated by the Air Force's 20th Special Operations Squadron.[131] This was the first and, as of 2024, the only time a stealth aircraft has been shot down by hostile ground fire in combat; the only other stealth aircraft in operation is the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber, only two of which have been lost, with both incidents being accidents.[132]

- Several times between 5 and 7 April 1999, Yugoslav MiG-29s were scrambled to intercept NATO aircraft, but turned back due to malfunctions.[125]

- On 7 April 1999 four RQ-5A Hunter UAVs were shot down.[133]

- On 30 April, some US sources claim that a second F-117A was damaged by a surface-to-air missile.[134] Although the aircraft returned to base, it supposedly never flew again.[135][136]

- On 2 May, a USAF F-16 was shot down near Šabac by a SA-3, again fired by the 3rd Battalion of the 250th Missile Brigade. The pilot Lt. Colonel David Goldfein, commander of the 555th Fighter Squadron, was rescued.[137] On the same day an A-10 Thunderbolt II was damaged by a Strela 2 shoulder-mounted SAM over Kosovo and had to make an emergency landing at a Skopje airport in Macedonia,[138] and a Marine Corps Harrier crashed while returning to the amphibious assault carrier USS Kearsarge from a training mission. Its pilot was rescued.[139]

- On 4 May, a Yugoslav MiG-29, piloted by Lt. Col. Milenko Pavlović, commander of the 204th Fighter Aviation Wing, was shot down at a low altitude over his hometown Valjevo by two USAF F-16s. Whilst attempting to chase A raid returning after bombing the town. The falling aircraft was possibly hit as well by Strela 2 fired by Yugoslav troops. Pavlović was killed.[128] He was shot down by Michael H. Geczy of the 78th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron.[140][141]

- On 11 May, an A-10 was lightly damaged over Kosovo by 9K35 Strela 10.[138][142]

- During the war NATO lost two AH-64 Apache strike helicopters (one on April 26 and the other on May 4 in Albania)[143] near the border with Yugoslavia, in training accidents resulting in death of two US Army crew members.[18]

- NATO reported that it lost 21 UAVs to technical failures or enemy action during the conflict, including at least seven German UAVs and five French UAVs. While the commander of the Yugoslav Third Army claimed that 21 NATO UAVs had been shot down by Yugoslav forces, another Yugoslav general claimed that Yugoslav air defences and ground forces had shot down 30 UAVs.[144] One of the preferred Yugoslav tactics to destroy hostile UAVs involved the use of transport helicopters in air-to-air combat role. The first IAI RQ-5 Hunter drone lost by the US Army in the campaign was apparently shot down by a Mi-8 helicopter flying alongside, with the door gunner firing a 7.62 mm machine gun. The manoeuvre was repeated several times until Allied air supremacy made this practice too dangerous.[145]

Air defence suppression operations

Suppression of Enemy Air Defences (SEAD) operations for NATO were principally carried out by the US Air Force, with fifty F-16CJ Block 50 Fighting Falcons, and the US Navy and Marines, with 30 EA-6B Prowlers. The F-16CJs carried AGM-88 HARM anti-radiation missiles which would home in on and destroy any active Yugoslav radar systems, while the Prowlers provided radar jamming assistance (though they could carry HARMs as well). Additional support came in the form of Italian and German Tornado ECRs which also carried HARMs.

USAF Compass Call EC-130s were used to intercept and jam Yugoslav communications, while RC-135s conducted bomb damage assessment.

The standard tactic for F-16CJs was for two pairs to come at a suspected air defence site from opposite directions, ensuring total coverage of the target area, and relaying information to incoming strike craft so they could adjust their flight path accordingly.[146]

Where possible, NATO attempted to proactively destroy air defence sites, using F-16CGs and F-15E Strike Eagles carrying conventional munitions including cluster bombs, AGM-130 boosted bombs, and AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon missiles.

Many NATO aircraft made use of new towed decoys designed to lure away any missiles fired at them. Reportedly, NATO also for the first time employed cyberwarfare to target Yugoslav air defence computer systems.[147]

A number of deficiencies in NATO's SEAD operations were revealed during the course of the bombing campaign. The EA-6Bs were noticeably slower than other aircraft, limiting their effectiveness in providing support, and land-based Prowlers flying out of Aviano Air Base were forced to carry extra fuel tanks instead of HARMs due to the distances involved.[146] The F-16CJ Block 50 could not carry the LANTIRN targeting pod, making it unable to conduct precision bombing at night.[148] Moreover, the US Air Force had allowed its electronic warfare branch to atrophy in the years after the Gulf War. Training exercises were fewer and less rigorous than before, while veterans with electronic warfare experience were allowed to retire with no replacement. The results were less than satisfactory: response times to engaging a SAM threat actually increased from the Gulf War, and electronic warfare wings could no longer reprogram their own jamming pods but had to send them elsewhere for the task.[149]

Further difficulties came in the form of airspace restrictions, which forced NATO aircraft into predictable flight paths, and rules of engagement which prevented NATO from targeting certain sites for fear of collateral damage. In particular this applied to early-warning radars located in Montenegro, which remained operational during the campaign and gave Yugoslav forces advanced warning of incoming NATO air raids.[150][146] Kosovo's mountainous terrain also made it difficult for NATO to locate and target Yugoslav air defences, while at the same time the region's poor infrastructure limited where Yugoslav SAM and AAA sites could be placed.[148]

Yugoslav air defences were much fewer than what Iraq had deployed during the Gulf War – an estimated 16 SA-3 and 25 SA-6 surface-to-air missile systems, plus numerous anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) and man-portable air defence systems (MANPADS) – but unlike the Iraqis they took steps to preserve their assets. Prior to the conflict's start Yugoslav SAMs were preemptively dispersed away from their garrisons and practiced emission control to decrease NATO's ability to locate them.[150] The Yugoslav integrated air defence system (IADS) was extensive, including underground command sites and buried landlines, which allowed for information to be shared between systems. Active radar in one area could target NATO aircraft for SAMs and AAA in another area with no active radar, further limiting NATO's ability to target air defence weapons.[151]

During the course of the campaign, NATO and Yugoslav forces engaged in a "cat-and-mouse" game which made suppressing the air defences difficult. Yugoslav SAM operators would turn their radars on for no longer than 20 seconds, allowing little chance for NATO anti-radiation missions to lock on to their emissions.[147] While most Yugoslav SAMs were fired ballistically (with no radar guidance) at NATO aircraft, as many as a third were guided by radar, forcing the targeted aircraft to jettison fuel tanks and take evasive action.[152] In response, over half of NATO's anti-radiation missiles were preemptively fired at suspected air defence sites so that if a radar system did become active the missiles would be able to lock on more quickly.[148]

Where possible, Yugoslav air defences attempted to bring NATO aircraft into range of AAA and MANPADS. A common tactic was to target the last aircraft in a departing formation, on the assumption that it received less protection, was flown by a less-experienced pilot, and/or was low on fuel needed to make evasive manoeuvres.[150] However, because AAA were limited to deploying close to roads for mobility and became bogged down in difficult terrain, NATO pilots learned to avoid these by staying at least five kilometers away from roads, never flying along them and only crossing them at a perpendicular angle, though this made spotting ground traffic more difficult.[148]

By focusing on their operational survival, Yugoslav air defences ceded a certain amount of air superiority to NATO forces. Yet the persistence of their credible SAM threat forced NATO to allocate greater resources to continued SEAD operations rather than conducting other missions, while Yugoslav AAA and MANPADS forced NATO aircraft to fly at 15,000 ft (4,600 m) or higher. NATO reportedly fired 743 HARMs during the course of the 78-day campaign, but could confirm the destruction of only 3 of the original 25 SA-6 batteries. Over 800 SAMs were fired by Yugoslav forces at NATO aircraft, including 477 SA-6s and 124 confirmed MANPADS, for the downing of only two aircraft and several more damaged.[147]

According to a post-conflict US intelligence report, Yugoslav military had a spy in NATO's headquarters in Brussels who in the early part of the conflict leaked flight plans and target details to the Yugoslav military, allowing Yugoslav military assets to move to avoid detection. Once NATO limited the number of people with access to its plans, the effect on "what the Serbs appeared to know" was immediate. The identity and nationality of the suspected "spy" was not stated.[153]

NATO forces

While not directly related to the hostilities, on 12 March 1999 the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland joined NATO by depositing instruments of accession in accordance with Article 10 of the North Atlantic Treaty at a ceremony in Independence, Missouri.[154] These nations did not participate directly in hostilities.

Aviation

During the 78 days of bombing, NATO aviation conducted 26,095 sorties, with an average of 334 flights per day. It is estimated that NATO launched 415,000 projectiles of various types on Yugoslav territory, including 350,000 cluster bombs and between 30,000 and 50,000 rounds of depleted uranium ammunition.[155]

A large element of the operation was the air forces of NATO, relying heavily on the US Air Force and Navy using the F-16, F-15, F-117, F-14, F/A-18, EA-6B, B-52, KC-135, KC-10, AWACS, and JSTARS from bases throughout Europe and from aircraft carriers in the region.

The French Navy and Air Force operated the Super Etendard and the Mirage 2000. The Italian Air Force operated with 34 Tornado, 12 F-104, 12 AMX, 2 B-707, the Italian Navy operated with Harrier II. The UK's Royal Air Force operated the Harrier GR7 and Tornado ground attack jets as well as an array of support aircraft. Belgian, Danish, Dutch, Norwegian, Portuguese and Turkish Air Forces operated F-16s. The Spanish Air Force deployed EF-18s and KC-130s. The Canadian Air Force deployed a total of 18 CF-18s, enabling them to be responsible for 10% of all bombs dropped in the operation.

The fighters were armed with both guided and unguided "dumb" munitions, including the Paveway series of laser-guided bombs.[citation needed] The bombing campaign marked the first time the German Air Force actively attacking targets since World War II.[156]

The US B-2 Spirit stealth bomber saw its first successful combat role in Operation Allied Force, striking from its home base in the contiguous United States.[citation needed]

Even with this air power, noted a RAND Corporation study, "NATO never fully succeeded in neutralising the enemy's radar-guided SAM threat".[157]

Space

Operation Allied Force incorporated the first large-scale use of satellites as a direct method of weapon guidance. The collective bombing was the first combat use of the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) kit, which uses an inertial-guidance and GPS-guided tail fin to increase the accuracy of conventional gravity munitions up to 95%. The JDAM kits were outfitted on the B-2s. The AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW) had been previously used in Operation Southern Watch earlier in 1999.

Naval

NATO naval forces operated in the Adriatic Sea. The Royal Navy sent a substantial task force that included the aircraft carrier HMS Invincible, which operated Sea Harrier FA2 fighter jets. The RN also deployed destroyers and frigates, and the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) provided support vessels, including the aviation training/primary casualty receiving ship RFA Argus. It was the first time the RN used cruise missiles in combat, fired from the nuclear fleet submarine HMS Splendid.

The Italian Navy provided a naval task force that included the aircraft carrier Giuseppe Garibaldi, a frigate (Maestrale) and a submarine (Sauro class).

The United States Navy provided a naval task force that included the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt, USS Vella Gulf, and the amphibious assault ship USS Kearsarge.

The French Navy provided the aircraft carrier Foch and escorts. The German Navy deployed the frigate Rheinland-Pfalz and Oker, an Oste-class fleet service ship, in the naval operations.

The Netherlands sent the submarine HNLMS Dolfijn to uphold trade embargoes off the coast of Yugoslavia.[158]

Army

NATO ground forces included a US battalion from the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division. The unit was deployed in March 1999 to Albania in support of the bombing campaign where the battalion secured the Tirana airfield, Apache helicopter refueling sites, established a forward-operating base to prepare for Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) strikes and offensive ground operations, and deployed a small team with an AN/TPQ-36 Firefinder radar system to the Albania/Kosovo border where it acquired targets for NATO air strikes. Immediately after the bombing campaign, the battalion was refitted back at Tirana airfield and issued orders to move into Kosovo as the initial entry force in support of Operation Joint Guardian. Task Force Hawk was also deployed.

Task Force Hunter, a US surveillance unit based upon the IAI RQ-5 Hunter drone "A" Company from a Forces Command (FORSCOM) Corps Military Intelligence Brigade (MI Bde) was deployed to Camp Able Sentry, Macedonia, in March, to provide real-time intelligence on Yugoslav forces inside Kosovo. They flew a total of 246 sorties,[citation needed] with five drones lost to enemy fire.[159] A German Army drone battery based at Tetovo was tasked with a similar mission. German forces used CL-289 UAVs from December 1998 to July 1999 to fly 237 sorties over Yugoslav positions, with six drones lost to hostile fire.[160][161]

Aftermath

Civilian casualties

Human Rights Watch concluded "that as few as 489 and as many as 528 Yugoslav civilians were killed in the ninety separate incidents in Operation Allied Force". Refugees were among the victims. Between 278 and 317 of the deaths, nearly 60 percent of the total number, were in Kosovo. In Serbia, 201 civilians were killed (five in Vojvodina) and eight died in Montenegro. Almost two-thirds (303 to 352) of the total registered civilian deaths occurred in twelve incidents where ten or more civilian deaths were confirmed.[162]

Military casualties

Military casualties on the NATO side were limited. According to official reports, the alliance suffered no fatalities from combat operations. However, on 5 May, an American AH-64 Apache crashed and exploded during a night-time mission in Albania.[163][164] The Yugoslavs claimed they shot it down, but NATO claimed it crashed due to a technical malfunction. It crashed 40 miles from Tirana,[165] killing the two crewmen, Army Chief Warrant Officers David Gibbs and Kevin Reichert.[166] It was one of two Apache helicopters lost in the war.[167] A further three US soldiers were ambushed and taken as prisoners of war by Yugoslav special forces while riding on a Humvee on a surveillance mission along the Macedonian border with Kosovo.[168] A study of the campaign reports that Yugoslav air defences may have fired up to 700 missiles at NATO aircraft, and that the B-1 bomber crews counted at least 20 surface-to-air missiles fired at them during their first 50 missions.[166] Despite this, only two NATO manned aircraft (one F-16C[169][170][171] and one F-117A Nighthawk)[172][173] were shot down.[174] A further F-117A Nighthawk was damaged by hostile fire[134][135] as were two A-10 Thunderbolt IIs.[175][176] One AV-8B Harrier crashed in the Adriatic Sea due to technical failure.[177] NATO also lost 25 UAVs, either due to enemy action or mechanical failure.[178] Yugoslavia's 3rd Army commander, Lt. Gen. Nebojsa Pavkovic, claimed that Yugoslav forces shot down 51 NATO aircraft, though no other source verified these numbers.[179]

In 2013, Serbia's then-defence minister Aleksandar Vučić announced that the combined Yugoslav military and law enforcement casualties during the air campaign amounted to 956 killed and 52 missing. Vučić stated that 631 soldiers were killed and a further 28 went missing, and that 325 policemen were also among the dead with a further 24 listed as missing.[180][181] The government of Serbia also lists 5,173 combatants as having been wounded.[182][183] In early June 1999, while the bombing was still in progress, NATO officials claimed that 5,000 Yugoslav troops had been killed in the bombing and a further 10,000 wounded.[184][185][186] NATO later revised this estimation to 1,200 soldiers and policemen killed.[187]

Throughout the war; 181 NATO strikes were reported against tanks, 317 against armoured personnel vehicles, 800 against other military vehicles, and 857 against artillery and mortars,[188] after a total of 38,000 sorties, or 200 sorties per day at the beginning of the conflict and over 1,000 at the end of the conflict.[189] When it came to alleged hits, 93 tanks (out of 600),[190] 153 APCs, 339 other vehicles, and 389 artillery systems were believed to have been disabled or destroyed with certainty.[25] The Department of Defence and Joint Chief of Staff had earlier provided a figure of 120 tanks, 220 APCs, and 450 artillery systems, and a Newsweek piece published around a year later stated that only 14 tanks, 12 self-propelled guns, 18 APCs, and 20 artillery systems had actually been obliterated,[25] not that far from the Yugoslavs' own estimates of 13 tanks, 6 APCs, and 6 artillery pieces.[179] However, this reporting was heavily criticised, as it was based on the number of vehicles found during the assessment of the Munitions Effectiveness Assessment Team, which wasn't interested in the effectiveness of anything but the ordnance, and surveyed sites that hadn't been visited in nearly three-months, at a time when the most recent of strikes were four-weeks old.[179] The Yugoslav Air Force also sustained serious damage, with 121 aircraft destroyed (according to NATO).[191]

Operation Allied Force inflicted less damage on the Yugoslav military than originally thought due to the use of camouflage and decoys. "NATO hit a lot of dummy and deception targets. It's an old Soviet ploy. Officials in Europe are very subdued", noted a former senior NATO official in a post-war assessment of the damage.[192] Other misdirection techniques were used to disguise targets including replacing the batteries of fired missiles with mock-ups, as well as burning tires beside major bridges and painting roads in different colors to emit varying degrees of heat, thus guiding NATO missiles away from vital infrastructure.[193] It was only in the later stages of the campaign that strategic targets such as bridges and buildings were attacked in any systematic way, causing significant disruption and economic damage. This stage of the campaign led to controversial incidents, most notably the bombing of the People's Republic of China embassy in Belgrade where three Chinese reporters were killed and twenty injured, which NATO claimed was a mistake.[99]

Relatives of Italian soldiers believe 50 of them have died since the war due to their exposure to depleted uranium weapons.[194] UNEP tests found no evidence of harm by depleted uranium weapons, even among cleanup workers,[195] but those tests and UNEP's report were questioned in an article in Le Monde diplomatique.[196]

Damage and economic loss

In April 1999, during the NATO bombing, officials in Yugoslavia said the damage from the bombing campaign cost around $100 billion up to that time.[197]

In 2000, a year after the bombing ended, Group 17 published a survey dealing with damage and economic restoration. The report concluded that direct damage from the bombing totalled $3.8 billion, not including Kosovo, of which only 5% had been repaired at that time.[198]

In 2006, a group of economists from the G17 Plus party estimated the total economic losses resulting from the bombing were about $29.6 billion.[199] This figure included indirect economic damage, loss of human capital, and loss of GDP.[citation needed]

The bombing caused damage to bridges, roads and railway tracks, as well as to 25,000 homes, 69 schools and 176 cultural monuments.[200] Furthermore, 19 hospitals and 20 health centers were damaged, including the University Hospital Center Dr Dragiša Mišović.[201][202] NATO bombing also resulted in the damaging of medieval monuments, such as Gračanica Monastery, the Patriarchate of Peć and the Visoki Dečani, which are on the UNESCO's World Heritage list today.[203] The Avala Tower, one of the most popular symbols of Belgrade, Serbia's capital, was destroyed during the bombing.[204]

The use of Depleted Uranium ammunition was noted by the UNEP, which cautioned about the risks for future groundwater contamination and recounted the "decontamination measures conducted by Yugoslavian, Serbian and Montenegrin authorities."[205] In total, between 9 and 11 tonnes of depleted uranium munitions were dropped across all of Yugoslavia, with payloads delivered by A-10 Thunderbolts and Tomahawk cruise missiles. In 2001, a study of uranium content across soil samples across Yugoslavia discovered highest concentration at Cape Arza, an area of land at the entrance to the Bay of Kotor.[41] Between 90 and 120 kilograms of depleted uranium was dropped on Cape Arza, despite the location being abandoned since World War One.[206][207]

Damage caused by the bombing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Political outcome

In early June, a Finnish-Russian mediation team headed by Martti Ahtisaari and Viktor Chernomyrdin traveled to Belgrade to meet with Milošević for talks on an agreement that would suspend air strikes.[209] When NATO agreed Kosovo would be politically supervised by the United Nations, and that there would be no independence referendum for three years, the Yugoslav government agreed to withdraw its forces from Kosovo, under strong diplomatic pressure from Russia, and the bombing was suspended on 10 June.[210] The Yugoslav Army and NATO signed the Kumanovo Agreement. Its provisions were considerably less draconian than what was presented at Rambouillet, most notably Appendix B was removed from the agreement.[211] Appendix B called for NATO forces to have free movement and to conduct military operations within the entire territory of Yugoslavia (including Serbia). The Yugoslav government had used it as a primary reason why they had not signed the Rambouillet accords, viewing it as a threat to its sovereignty.[212]

The war ended 11 June, and Russian paratroopers seized Slatina airport to become the first peacekeeping force in the war zone.[213] As British troops were still massed on the Macedonian border, planning to enter Kosovo at 5:00 am, the Serbs were hailing the Russian arrival as proof the war was a UN operation, not a NATO operation.[210] After hostilities ended on 12 June, the US Army's 82nd Airborne, 2–505th Parachute Infantry Regiment entered Kosovo as part of Operation Joint Guardian.[214]

Yugoslav President Milošević survived the conflict, however, he was indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia along with a number of other senior Yugoslav political and military figures.[215] His indictment led to Yugoslavia as a whole being treated as a pariah by much of the international community because Milošević was subject to arrest if he left Yugoslavia.[210] The country's economy was badly affected by the conflict, and in addition to electoral fraud, this was a factor in the overthrow of Milošević.[210][216]

Thousands were killed during the conflict, and hundreds of thousands more fled from the province to other parts of the country and to the surrounding countries.[217] Most of the Albanian refugees returned home within a few weeks or months. However, much of the non-Albanian population again fled to other parts of Serbia or to protected enclaves within Kosovo following the operation.[218][219][220][221][222] Albanian guerrilla activity spread into other parts of Serbia and to the neighbouring Republic of Macedonia, but subsided in 2001.[223] The non-Albanian population has since diminished further following fresh outbreaks of inter-communal conflict and harassment.[224]

In December 2002, Elizabeth II approved the awarding of the Battle Honour "Kosovo" to squadrons of the RAF that participated in the conflict. These were: Nos 1, 7, 8, 9, 14, 23, 31, 51, 101, and 216 squadrons.[225][226] This was also extended to the Canadian squadrons deployed to the operation, 425 and 441.[227]

Ten years after the operation, the Republic of Kosovo declared independence with a new Republic of Kosovo government.[228]

KFOR

On 12 June, KFOR began entering Kosovo. Its mandate among other things was to deter hostilities and establish a secure environment, including public safety and civil order.[229]

KFOR, a NATO force, had been preparing to conduct combat operations, but in the end, its mission was only peacekeeping. It was based upon the Allied Rapid Reaction Corps headquarters commanded by then Lieutenant General Mike Jackson of the British Army. It consisted of British forces (a brigade built from 4th Armoured and 5th Airborne Brigades), a French Army Brigade, a German Army brigade, which entered from the west while all the other forces advanced from the south, and Italian Army and US Army brigades.

The US contribution, known as the Initial Entry Force, was led by the US 1st Armoured Division. Subordinate units included TF 1–35 Armour from Baumholder, Germany, the 2nd Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment from Fort Bragg, North Carolina, the 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit from Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, the 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry Regiment from Schweinfurt, Germany, and Echo Troop, 4th Cavalry Regiment, also from Schweinfurt, Germany. Also attached to the US force was the Greek Army's 501st Mechanised Infantry Battalion. The initial US forces established their area of operation around the towns of Uroševac, the future Camp Bondsteel, and Gnjilane, at Camp Monteith, and spent four months – the start of a stay which continues to date – establishing order in the southeast sector of Kosovo.

The first NATO troops to enter Pristina on 12 June 1999 were Norwegian special forces from the Forsvarets Spesialkommando (FSK) and soldiers from the British Special Air Service 22 S.A.S, although to NATO's diplomatic embarrassment Russian troops arrived first at the airport. The Norwegian soldiers from FSK were the first to come in contact with the Russian troops at the airport. FSK's mission was to level the negotiating field between the belligerent parties, and to fine-tune the detailed, local deals needed to implement the peace deal between the Serbians and the Kosovo Albanians.[230][231][232][233]

During the initial incursion, US soldiers were greeted by Albanians cheering and throwing flowers as US soldiers and KFOR rolled through their villages.[citation needed] Although no resistance was met, three US soldiers from the Initial Entry Force were killed in accidents.[234]

Following the military campaign, the involvement of Russian peacekeepers proved to be tense and challenging to the NATO Kosovo force. The Russians expected to have an independent sector of Kosovo, only to be unhappily surprised with the prospect of operating under NATO command. Without prior communication or coordination with NATO, Russian peacekeeping forces entered Kosovo from Bosnia and seized Pristina International Airport.[citation needed]

In 2010, James Blunt in an interview described how his unit was given the assignment of securing the Pristina in advance of the 30,000-strong peacekeeping force and the Russian army had moved in and taken control of the airport before his unit's arrival. As the first officer on the scene, Blunt shared a part in the difficult task of addressing the potentially violent international incident. His own account tells of how he refused to follow orders from NATO command to attack the Russians.[235]

Outpost Gunner was established on a high point in the Preševo Valley by Echo Battery 1/161 Field Artillery in an attempt to monitor and assist with peacekeeping efforts in the Russian sector. Operating under the support of 2/3 Field Artillery, 1st Armoured Division, the Battery was able to successfully deploy and continuously operate a Firefinder Radar which allowed the NATO forces to keep a closer watch on activities in the sector and the Preševo Valley. Eventually a deal was struck whereby Russian forces operated as a unit of KFOR but not under the NATO command structure.[236]

Attitudes towards the campaign

In favor of the campaign

Those who were involved in the NATO airstrikes have stood by the decision to take such action. US President Bill Clinton's Secretary of Defense, William Cohen, said, "The appalling accounts of mass killing in Kosovo and the pictures of refugees fleeing Serb oppression for their lives makes it clear that this is a fight for justice over genocide."[237] On CBS' Face the Nation Cohen claimed, "We've now seen about 100,000 military-aged men missing. ... They may have been murdered."[238] Clinton, citing the same figure, spoke of "at least 100,000 (Kosovar Albanians) missing".[239] Later, Clinton said about Yugoslav elections, "they're going to have to come to grips with what Mr. Milošević ordered in Kosovo. ... They're going to have to decide whether they support his leadership or not; whether they think it's OK that all those tens of thousands of people were killed. ..."[240] In the same press conference, Clinton also said, "NATO stopped deliberate, systematic efforts at ethnic cleansing and genocide."[240] Clinton compared the events of Kosovo to the Holocaust. CNN reported, "Accusing Serbia of 'ethnic cleansing' in Kosovo similar to the genocide of Jews in World War II, an impassioned Clinton sought Tuesday to rally public support for his decision to send US forces into combat against Yugoslavia, a prospect that seemed increasingly likely with the breakdown of a diplomatic peace effort."[241]

President Clinton's Department of State also claimed Yugoslav troops had committed genocide. The New York Times reported, "the Administration said evidence of 'genocide' by Serbian forces was growing to include 'abhorrent and criminal action' on a vast scale. The language was the State Department's strongest up to that time in denouncing Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević."[242] The Department of State also gave the highest estimate of dead Albanians. In May 1999, Defence Secretary William Cohen suggested that there might be up to 100,000 Albanian fatalities."[243] Post-war examinations revealed these statements and casualty figures to have been exaggerated.[244][245]

Five months after the conclusion of NATO bombing, when around one third of reported gravesites had been visited thus far, 2,108 bodies had been found, with an estimated total of between 5,000 and 12,000 at that time;[246] Yugoslav forces had systematically concealed grave sites and moved bodies.[247][248] Since the war's end, after most of the mass graves had been searched, the body count has remained less than half of the estimated 10,000 plus. It is unclear how many of these were victims of war crimes.[249]

The United States House of Representatives passed a non-binding resolution on 11 March 1999 by a vote of 219–191 conditionally approving of President Clinton's plan to commit 4,000 troops to the NATO peacekeeping mission.[250] In late April, the House Appropriations Committee approved $13 billion in emergency spending to cover the cost of the air war, but a second non-binding resolution approving of the mission failed in the full House by a vote of 213–213.[251] The Senate had passed the second resolution in late March by a vote of 58–41.[252]

Criticism of the campaign

There has also been criticism of the campaign. The Clinton administration and NATO officials were accused of inflating the number of Kosovar Albanians killed by Serbs.[253][254] The media watchdog group Accuracy in Media charged the alliance with distorting the situation in Kosovo and lying about the number of civilian deaths to justify US involvement in the conflict.[255] Other journalists have asserted that NATO's campaign triggered or accelerated the ethnic cleansing in Kosovo, which was the opposite of the alliance's stated aim, as prior to it Yugoslav forces limited their activities.[256][257][258]

In an interview with Radio-Television Serbia journalist Danilo Mandić on 25 April 2006, Noam Chomsky referred to the foreword to John Norris' 2005 book Collision Course: NATO, Russia, and Kosovo, in which Strobe Talbott, the Deputy Secretary of State under President Clinton and the leading US negotiator during the war, had written that "It was Yugoslavia's resistance to the broader trends of political and economic reform – not the plight of Kosovar Albanians – that best explains NATO's war."[259] On 31 May 2006, Brad DeLong rebutted Chomsky and quoted from elsewhere in the passage which Chomsky had cited,[260] "the Kosovo crisis was fueled by frustration with Milošević and the legitimate fear that instability and conflict might spread further in the region" and also that "Only a decade of death, destruction, and Milošević brinkmanship pushed NATO to act when the Rambouillet talks collapsed. Most of the leaders of NATO's major powers were proponents of 'third way' politics and headed socially progressive, economically centrist governments. None of these men were particularly hawkish, and Milošević did not allow them the political breathing room to look past his abuses."[260][261]

The United Nations Charter does not allow military interventions in other sovereign countries with few exceptions which, in general, need to be decided upon by the United Nations Security Council. The issue was brought before the UNSC by Russia, in a draft resolution which, inter-alia, would affirm "that such unilateral use of force constitutes a flagrant violation of the United Nations Charter". China, Namibia and Russia voted for the resolution, the other members against, thus it failed to pass.[262][263][dead link] William Blum wrote that "Nobody has ever suggested that Serbia had attacked or was preparing to attack a member state of NATO, and that is the only event which justifies a reaction under the NATO treaty."[264]

Prime Minister of India Atal Bihari Vajpayee condemned the NATO bombing, and demanded a halt on the airstrikes and for the matter to be taken up by the United Nations. Since Yugoslavia was part of the Non-Aligned Movement, he announced that he would raise the issue at the forum. At a speech in a political rally in May 1999, Vajpayee said that "NATO is blindly bombing Yugoslavia" and "There is a dance of destruction going on there [Yugoslavia]. Thousands of people rendered homeless. And the United Nations is a mute witness to all this. Is NATO's work to prevent war or to fuel one?"[265][266]

Israeli Minister of Foreign Affairs Ariel Sharon criticised the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia as an act of "brutal interventionism" and said Israel was against "aggressive actions" and "hurting innocent people" and hoped "the sides will return to the negotiating table as soon as possible".[267]

On 29 April 1999, Yugoslavia filed a complaint at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at The Hague against ten NATO member countries (Belgium, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Canada, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the United States) and alleged that the military operation had violated Article 9 of the 1948 Genocide Convention and that Yugoslavia had jurisdiction to sue through Article 38, para. 5 of Rules of Court.[268] On 2 June, the ICJ ruled in an 8–4 vote that Yugoslavia had no such jurisdiction.[269] Four of the ten nations (the United States, France, Italy and Germany) had withdrawn entirely from the court's "optional clause." Because Yugoslavia filed its complaint only three days after accepting the terms of the court's optional clause, the ICJ ruled that there was no jurisdiction to sue either Britain or Spain, as the two nations had only agreed to submit to ICJ lawsuits if a suing party had filed their complaint a year or more after accepting the terms of the optional clause.[269] Despite objections that Yugoslavia had legal jurisdiction to sue Belgium, the Netherlands, Canada and Portugal,[269] the ICJ majority vote also determined that the NATO bombing was an instance of "humanitarian intervention" and thus did not violate Article 9 of the Genocide Convention.[269]

Amnesty International released a report which stated that NATO forces had deliberately targeted a civilian object (NATO bombing of the Radio Television of Serbia headquarters), and had bombed targets at which civilians were certain to be killed.[270][271] The report was rejected by NATO as "baseless and ill-founded". A week before the report was released, Carla Del Ponte, the chief prosecutor for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia had told the United Nations Security Council that her investigation into NATO actions found no basis for charging NATO or its leaders with war crimes.[272]

A majority of US House Republicans voted against two resolutions, both of which expressed approval for American involvement in the NATO mission.[273][274]

Moscow criticised the bombing as a breach of international law and a challenge to Russia's status.[275]

Believing that the US bombing of China's embassy in Belgrade was intentional, Chinese leadership worried that China was significantly lacking in leverage against the United States.[276]: 17 To reduce its gap in strategic leverage, China focused on developing "information age" weapons including counterspace capabilities and cyberspace capabilities, and enhanced its efforts to develop precision missiles.[276]: 17 China also began a process of upgrading its integrated air defense system[276]: 127 and accelerated plans to expand its conventional missile forces.[276]: 132 Chinese leadership was also concerned that NATO's rationale behind intervention without UN Security Council approval (supporting what NATO viewed as Kosovo's claim to self-determination) could also be used by the US to intervene in Taiwan or China's sensitive border areas.[276]: 185

About 2,000 Serbian Americans and anti-war activists protested in New York City against NATO airstrikes, while more than 7,000 people protested in Sydney.[277] Substantial protests were held in Greece, and demonstrations were also held in Italian cities, Moscow, London, Toronto, Berlin, Timișoara, Stuttgart, Salzburg and Skopje.[277]

See also

- Legitimacy of NATO bombing of Yugoslavia

- List of NATO bombings

- Operation Deliberate Force

- Operation Horseshoe

- Responsibility to protect

- War crimes in the Kosovo War

- Allied Rapid Reaction Corps

- 1999 NATO bombing of Novi Sad

- Grdelica train bombing

- Incident at Pristina airport

- Prizren Incident (1999)

- Air Force of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro)

- Operation Eagle Eye (Kosovo)

- Bombing of Belgrade in World War II

References

- ^ Reidun J. Samuelsen (26 March 1999). "Norske jagerfly på vingene i går". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ "Turkish Air Force". Hvkk.tsk.tr. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ^ "NATO & Kosovo: Index Page". nato.int. Archived from the original on 12 September 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ "NATO hits Montenegro, says Milosevic faces dissent" Archived 9 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, CNN, 29 April 1999.

- ^ References:

- Stigler, Andrew L. "A clear victory for air power: NATO's empty threat to invade Kosovo." International Security 27.3 (2003): 124–157.

- Biddle, Stephen. "The new way of war? Debating the Kosovo model." (2002): 138–144.

- Dixon, Paul. "Victory by spin? Britain, the US and the propaganda war over Kosovo." Civil Wars 6.4 (2003): 83–106.

- Harvey, Frank P. "Getting NATO's success in Kosovo right: The theory and logic of counter-coercion." Conflict Management and Peace Science 23.2 (2006): pp. 139–158.

- ^ Stigler, Andrew L. "A clear victory for air power: NATO's empty threat to invade Kosovo." International Security 27.3 (2003): pp. 124–157.

- ^ Biddle, Stephen. "The new way of war? Debating the Kosovo model." (2002): 138–144.

- ^ Dixon, Paul. "Victory by spin? Britain, the US and the propaganda war over Kosovo." Civil Wars 6.4 (2003): pp. 83–106.

- ^ Harvey, Frank P. "Getting NATO's success in Kosovo right: The theory and logic of counter-coercion." Conflict Management and Peace Science 23.2 (2006): pp. 139–158.

- ^ Parenti (2000), pp. 198

- ^ "Serbia marks another anniversary of NATO attacks– English– on B92.net". Archived from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ^ Zunes, Stephen (6 July 2009). "The US War on Yugoslavia: Ten Years Later". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Abuses against Serbs and Roma in the new Kosovo". Human Rights Watch. August 1999. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ Hudson, Robert; Bowman, Glenn (2012). After Yugoslavia: Identities and Politics Within the Successor States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 30. ISBN 9780230201316.

- ^ "Kosovo Crisis Update". United Nations High Commission for Refugees. 4 August 1999. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Siobhán Wills (26 February 2009). Protecting Civilians: The Obligations of Peacekeepers. Oxford University Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-19-953387-9. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "Operation Allied Force – Operation Allied Force in Kosovo". Militaryhistory.about.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ a b Lambeth, Benjamin S. "Task Force Hawk". Airforce-magazine.com. Archived from the original on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ "Report to Congress: Kosovo operation allied force after-action report" (PDF). au.af.mil: 31–32. 30 January 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ a b "NATO Operation Allied Force". Defense.gov. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ NATOs AirWar for Kosovo, Benjamin S. Lambert

- ^ "Officially confirmed / documented NATO UAV losses". 8 March 2001. Archived from the original on 8 March 2001.

- ^ "Stradalo 1.008 vojnika i policajaca". RTS. 11 February 2013. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Human losses in NATO bombing (Serbia Kosovo, Montenegro)". FHP. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Lambeth, p. 86

- ^ a b c Grant, Rebecca (1 August 2000). "True Blue: Behind the Kosovo Numbers Game". Air & Space Forces Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 September 2024. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ a b "Civilian Deaths in the NATO Air Campaign – The Crisis in Kosovo". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- ^ „Шеснаеста годишњица НАТО бомбардовања“ Archived 29 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, РТС, 24. март 2015.

- ^ Bonnén, Preben (2003). Towards a common European security and defence policy: the ways and means of making it a reality. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster. p. 188. ISBN 978-3-8258-6711-9.

- ^ RTS: "Порекло имена 'Милосрдни анђео'" ("On the origin of the name 'Merciful Angel'") Archived 2 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 26 March 2009 (in Serbian)

- ^ Jordan, Robert S. (2001). International organizations: A comparative approach to the management of cooperation. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 129. ISBN 9780275965495.

- ^ Yoshihara, Susan Fink (2006). "Kosovo". In Reveron, Derek S.; Murer, Jeffrey Stevenson (eds.). Flashpoints in the War on Terrorism. Routledge. pp. 67–68. ISBN 9781135449315.

- ^ a b Suy, Eric (2000). "NATO's Intervention in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia". Leiden Journal of International Law. 13. Cambridge University Press: 193–205. doi:10.1017/S0922156500000133. S2CID 145232986. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022.

- ^ Bjola, p. 175

- ^ a b c NATO (12 April 1999). "The situation in and around Kosovo". nato.int. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ^ O'Connell, Mary Ellen (2000). "The UN, NATO, and International Law after Kosovo". Human Rights Quarterly. 22 (1): 57–89. doi:10.1353/hrq.2000.0012. ISSN 0275-0392. JSTOR 4489267. S2CID 146137597.

- ^ "Security Council Rejects Demand for Cessation of Use of Force Against Federal Republic of Yugoslavia". SC/6659. United Nations. Security Council. 26 March 1999.

- ^ Daalder, Ivo H.; O'Hanlon, Michel E. (2000). Winning Ugly: NATO's War to Save Kosovo (2004 ed.). Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0815798422. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 2 January 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Kosovo Memory Book Database Presentation and Expert Evaluation" (PDF). Humanitarian Law Center. 4 February 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ Judah, Tim (1997). The Serbs: History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia (2009, 3rd ed.). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-300-15826-7. Retrieved 3 January 2021 – via Google Books.

the Serbian police began clearing ... people [who] were marched down to the station and deported... the UNCHR registered 848,000 people who had either been forcibly expelled or had fled

- ^ a b Miljević, Nada; Marković, Mirjana; Todorović, Dragana; Cvijović, Mirjana; Dušan, Golobočanin; Orlić, Milan; Veselinović, Dragan; Biočanin, Rade (2001). "Uranium content in the soil of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia after NATO intervention" (PDF). Archive of Oncology. 9 (4): 245–249. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Abuses against Serbs and Roma in the new Kosovo". Human Rights Watch. August 1999. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ Hudson, Robert; Bowman, Glenn (2012). After Yugoslavia: Identities and Politics Within the Successor States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 30. ISBN 9780230201316.

- ^ "Kosovo Crisis Update". United Nations High Commission for Refugees. 4 August 1999. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ "Forced Expulsion of Kosovo Roma, Ashkali and Egyptians from OSCE Participated state to Kosovo". OSCE. 6 October 2006. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Siobhán Wills (2009). Protecting Civilians: The Obligations of Peacekeepers. Oxford University Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-19-953387-9. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "Serbia home to highest number of refugees and IDPs in Europe". B92. 20 June 2010. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ "Serbia: Europe's largest proctracted refugee situation". OSCE. 2008. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ S. Cross, S. Kentera, R. Vukadinovic, R. Nation (2013). Shaping South East Europe's Security Community for the Twenty-First Century: Trust, Partnership, Integration. Springer. p. 169. ISBN 9781137010209. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zyla, Benjamin (2020). The End of European Security Institutions?: The EU's Common Foreign and Security Policy and NATO After Brexit. Springer. p. 40. ISBN 9783030421601. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ The Prosecutor vs Milan Milutinović et al. – Judgement, 26 February 2009, p. 416.

- ^ "The Rambouillet text – Appendix B". The Guardian. 28 April 1999. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ "The Last War of the 20th century" (PDF). p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Judah (2009). The Serbs. Yale University Press. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-300-15826-7.

- ^ Kosovo: A Short History p. 39. Chapter: Preface to the second edition

- ^ John Keegan, "Please, Mr Blair, never take such a risk again" Archived 25 November 2004 at the Wayback Machine. Telegraph, London, 6 June 1999.

- ^ K. Webb, 'Strategic Bombardment & Kosovo: Evidence from the Boer War', Defense & Security Analysis, September 2008, Volume 24, Edition 3

- ^ Gray in Cox and Gray 2002, p. 339

- ^ Andrew Gilligan, "Russia, not bombs, brought end to war in Kosovo, says Jackson" Archived 14 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Telegraph, 2 April 1998

- ^ Ritche in Cox and Gray 2002, p. 328.

- ^ Lambeth, 2001, pp. 69–70

- ^ a b Hosmer, 2001, p. 117

- ^ Hosmer, 2001, pp. 88–89

- ^ General Wesley Clark, Waging Modern War, (New York: Public Affairs, 2001), pp. 305, 425

- ^ Lambeth, 2001, p. 74

- ^ Ritchie in Cox and Gray 2002, p. 325

- ^ Ritchie in Cox and Gray 2002, p. 328

- ^ Perlez, Jane (22 March 1999). "Conflict in the Balkans: The Overview; Milosevic to Get One 'Last Chance' to Avoid Bombing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ "Kosovo Verification Mission (Closed)". Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ a b "Nato poised to strike". BBC News. 23 March 1999. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ a b Gellman, Barton (24 March 1999). "NATO Mobilizes for Attack / Yugoslavia declares state of emergency". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Press Statement by Dr. Javier Solana, Secretary General of NATO" (Press release). NATO. 23 March 1999. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "1999 - Operation Allied Force". Air Force Historical Support Division. United States Department of the Air Force. Retrieved 27 March 2025.

- ^ Independent International Commission on Kosovo (2000). The Kosovo Report: Conflict, International Response, Lessons Learned. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-924309-9.

- ^ "Press Statement by Dr. Javier Solana, NATO Secretary General following the Commencement of Air Operations" (Press release). NATO. 24 March 1999. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Spain Signs Deal to Keep Its F/A-18 Hornet Fighter Jets Combat-Ready". Global Defense News. No. Defense News Aerospace 2024. Army Recognition Group. 12 September 2024. Retrieved 27 March 2025.

- ^ Polmar, Norman; Allen, Thomas B. (February 2016). "The TLAM - Naval Weapon of Choice". Naval History. Vol. 30, no. 1. U.S. Naval Institute. Retrieved 27 March 2025.