National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa | |

|---|---|

| (Formerly the Fagatele Bay National Marine Sanctuary)[1] | |

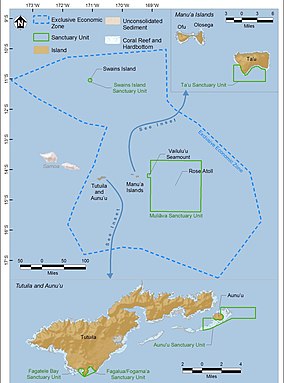

Map of the National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa | |

| |

| Location | American Samoa:

|

| Coordinates | 14°21′54″S 170°45′54″W / 14.365°S 170.765°W[a] |

| Area | 13,581 sq mi (35,170 km2) |

| Established |

|

| Governing body | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| americansamoa | |

The National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa (formerly the Fagatele Bay National Marine Sanctuary[1]) is a federally-designated underwater area protected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. This sanctuary is the largest and most remote in the National Marine Sanctuary system.[2] Spanning 13,581 sq mi,[2][3] it is thought to be home to the greatest biodiversity of aquatic species of all the marine sanctuaries.[2][4][5] Among them are expansive coral reefs, including some of the oldest Porites coral heads on earth, deep-water reefs, hydrothermal vent communities, and rare archeological resources.[1] It was established as Fagatele Bay National Marine Sanctuary on April 29, 1986,[6] it is thought to be home to the greatest biodiversity of aquatic species of all the marine sanctuaries.[2][4] and then expanded and renamed in 2012.

The American Samoa archipelago is located in the mid-south Pacific Ocean, halfway between Hawaii and New Zealand.[7] It is the only American Territory south of the equator.[7] The Park has one visitor center in Tutuila, known as Tauese P.F. Sunia Ocean Center.[8][9] There are exhibits for all ages, and it is open year-round.[9]

Description

[edit]The National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa comprises six protected areas: Fagatele Bay and Fagalua/Fogama`a (the bay east of Fagatele) on the island of Tutuila, areas at Aunuʻu, Taʻū, Swains Island, and Rose Atoll, after major additions in protected areas during 2012.[10] It is the only true tropical reef within the National Marine Sanctuary program, and is also the most remote.[11][5]

The Fagatele Bay portion of the sanctuary is completely contained in the 0.25 square miles (0.65 km2) of the bay formed by an eroded volcanic crater . The land surrounding the bay resides in the hands of the families who have lived near the bay's slopes for thousands of years. Fortunately, there is little development in the watershed and the one reliable stream that empties near the beach runs clear and clean.

The fringing coral reef ecosystem nestled within Fagatele Bay is a vibrant tropical marine ecosystem, filled with all sorts of brightly colored tropical fish, including parrot fish, damselfish and butterfly fish, as well as other sea creatures like lobster, crabs, sharks and octopus. From June to September, southern humpback whales migrate north from Antarctica to calve and court in Samoan waters. Visitors can hear courting males sing whale songs, which the whales may be using to attract mates. Several species of dolphin and threatened and endangered species of sea turtles, such as the hawksbill and green sea turtle, are frequently seen swimming in the bay. Recreational activities such as diving, snorkeling, and fishing can be enjoyed at the sanctuary.[4]

Fagatele Bay as a Marine Sanctuary

[edit]

Fagatele Bay National Marine Sanctuary was designated in 1986[12] in response to a proposal from the American Samoa Government to the National Marine Sanctuary Program. The National Marine Sanctuary Program supports research in all of its 14 sites. Research plays a role in management by supplying information needed to make resource protection decisions based on hard scientific data. Fagatele Bay's most important research project spans over a decade. In the late 1970s, millions of Acanthaster planci or crown-of-thorns starfish (alamea), a coral-eating animal, ate their way through Tutuila's reefs. More than 90 percent of all the living corals were destroyed.[11] At the time, Fagatele Bay was not a National Marine Sanctuary, but this disaster propelled the decision for the site's designation.

The National Marine Sanctuary Program protects and preserves nature and local culture. The program is found in areas of special significance such as the oceans and Great Lakes of the United States. There are 14 sanctuaries in the program ranging from Stellwagen Bank off Cape Cod to the Channel Islands in southern California. All manage their precious resources through a combination of education, research, long-term monitoring, regulation and enforcement.

Many different types of fish call this reef home, and many biologists and marine researchers attempt to cooperate with the local government in an effort to find new species within the local waters. Many new species have been found, but as it is a marine sanctuary, fish or other marine animals cannot be removed from the ecosystem. Scientists, headed up by Dr. Charles Birkenland, used the starfish's destruction as a focus of their long-term research: to follow the recovery of a coral reef. Because corals grow slowly, the research team chose a multi-year cycle of data collection. Beginning in 1985, and again in 1988, 1995, 1998, 2001 and 2004, the team amassed information on coral, fishes, invertebrates and marine plants. This database is unique for Samoa and the study is one of the few long-running surveys of its type in the world

Climate Change

[edit]An increase in greenhouse gas emissions have caused a rise in global temperatures. This phenomenon, known as global warming or climate change, is beginning to impact Earth's most treasured natural spaces, and the Samoan Islands are among the most vulnerable regions.[13] This rise in CO2 and temperature causes an imbalance in the Samoan reef ecosystem in a myriad of ways, which will be described below.

Ocean Acidification

[edit]Since 1750, the acidity of the ocean has increased by 30%.[14] An increase in ocean acidification destabilizes Samoan reefs by impacting crustose corraline algae,[14] a calcareous species that consolidates and cements reefs together.[15] A reduction in coral calcification impairs coral growth and density, increasing vulnerability to erosion and damage.[16] The increase in acidification also makes it difficult for clams in all stages of life to grow their shells, and for the larvae of corral reef fish to grow, survive, and make it back to the reef.[14] It is projected that by 2060, the aragonite (CaCO3) saturation state that is crucial to coral growth will fall below the optimal threshold of 4.0 to 3.5, and continue deteriorating in the future.[13][14]

Rising Water Temperatures

[edit]The oceans absorb much of the heat caused due to increase in global temperature.[14] Waters in American Samoa have risen 1.8F in the past 30 years, and are projected to increase 4.7F by 2090.[13][14]

Extreme temperature events, also known as heatwaves, have also increased in frequency.[14] Coupled with the rise in ocean temperature, these heatwaves cause coral bleaching events, wherein symbiotic algae are expelled from the coral, causing the corals to appear white.[14] These algae provide food and process waste from the corals, hence are extremely essential to their survival.[14] Six mass bleaching events have occurred from 1994 to 2020, with the 2015 event causing the most damage.[17][14] These events are projected to become more frequent and intense in the future.[14] It is estimated that the reefs of the American Samoa could experience yearly bleaching by the year 2040.[14][16]

By the year 2115, under extreme warming, it is projected that water temperatures in this region may be too high for species currently living in the reefs.[14] Due to the isolation of the Samoan reefs, species may not be able to find another suitable habitat.[14] Warming temperatures may also worsen coral diseases and favor invasive species, such as the outbreaks of the crown-of-thorns sea star, a predator of the coral.[14] Algal blooms will also become more expansive and longer-lasting.[13][14] Some of these blooms may also be Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) and become toxic to life around it.[13][14]

Changing Weather Patterns and Storms

[edit]In the American Samoa, climate change is estimated to increase rainfall by about 10% by 2100,[14] while extreme precipitation events are also projected to increase in frequency.[14] These extreme events cause large amounts of sediment runoff, which bury corals, suffocating and killing them.[14][16] This sediment also clouds up the water, making photosynthesis challenging.[14] Nitrogen from fertilizers increase coral disease and contribute to coral bleaching.[13][16][14]

Tropical cyclones drive harsh winds and towering waves that cause damage to coral systems, sometimes causing persistent decrease in coral cover.[14] These storms are expected to increase in intensity, but decrease in frequency over the next 70 years.[13][14]

Actions Being Taken

[edit]The NOAA Ocean Acidification Program placed a very scientifically powerful buoy in Fagatele Bay in May 2019.[14] This buoy records real-time values of water temperature, acidity, and other relevant parameters, that can then be used to assess trends.[14] NOAA also tackles non-climate stressors that can make the reefs more resilient as a whole.[14] The population of crown-of-thorns sea star, a natural predator of corals, is closely monitored and controlled to prevent outbreaks.[14] The sea stars are injected with ox bile that painlessly kills them and does not harm the rest of the ecosystem.[14] A coral nursery project was also piloted in 2020.[14] In the future, corals from the nursery could be used to restore reefs after devastation due to weather or other events.[14]

Education

[edit]The sanctuary sponsors education programs, such as the EnviroDiscoveries Camp, which is an outdoor activity and learning camp for 8- to 12-year-olds. Scientific programs include a continuing resource assessment survey, begun in 1985, and coral reef monitoring. Sanctuary regulations prohibit taking invertebrates and sea turtles, as well as historical artifacts. Only traditional fishing methods are permitted in the inner bay.

The sanctuary makes a special effort to work with the American Samoan community with outreach programs for all ages. The sanctuary co-sponsors a summer environmental education program for 8- to 12-year-old children. These programs explore the marine life in the bay, including ancient reef-dwellers and solar-powered clams, teaching ways to protect the resources there. Samoan cultural events and general community outreach/education programs are also run year-round.[18]

The sanctuary also provides guided tours of the area, and allows any student to come on field-trips, for which they provide educational guides. They also emphasize the cultural aspects of the reefs and the wildlife, so as to combine traditional culture with the scientific knowledge students learn in school. The sanctuary also aids local education by organizing projects for the High Schoolers on the island, to further reinforce the necessity of the National Marine Sanctuary.

Big Momma

[edit]

Also known as Big Mama and Fale Bommie,[19] Big Momma is the biggest known coral on Earth.[20] It is located in the Valley of Giants in the National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa.[21] It is 21-foot (6.4 m) tall, and its circumference is 134 feet (41 m). It is over 500 years old. Its scientific name is Porites lobata.[21]

Animals

[edit]- Grouper: Cephalopholis or Epinephelus

- Parrot fish: Bolbometopon muricatum, Leptoscarus viagiensis, Sparisoma viride, Scarus iseri and Sparisoma cretense

- Damselfish: Chromis chromis

- Butterfly fish: Chaetodon lineolatus, Chaetodon lunula

- Southern humpback whales: Megaptera

- Dolphin: Delphinus capensis, Tursiops truncatus, Stenella longirostris, Lagenorhynchus obliquidens,

- Hawksbill sea turtle: Eretmochelys imbricata

- Green sea turtle: Chelonia mydas

- Starfish: Acanthaster planci, Linckia laevigata

Staff

[edit]Americorps volunteers assist the outreach program. Staff members are American Samoa Government employees based in Pago Pago, American Samoa and operate through a cooperative agreement between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and American Samoa's Economic and Development Planning Office, as well as the National Marine Sanctuary Association (NMSA). The volunteers typically work for 3 months and then take the rest of the time off, but a volunteer can work enough to become a paid worker for the NMSA or even take a Manager position at another Marine Sanctuary.[citation needed]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c http://americansamoa.noaa.gov National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa. NOAA.gov. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d "NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY OF AMERICAN SAMOA ABOUT THE SANCTUARY".

- ^ "National Marine Sanctuary". Visit American Samoa. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ a b c "National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa". Recreation.gov. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ a b "Fagatele Bay | Ocean Futures Society". www.oceanfutures.org. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ "Sanctuary Designations & Expansions". NOAA. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "Location & maps | Office of National Marine Sanctuaries". americansamoa.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ "Tauese PF Sunia Ocean Center | American Samoa Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ a b "Visit | National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa". americansamoa.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ https://americansamoa.noaa.gov/about/ National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa. NOAA.gov. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ a b Fenner, Douglas. "The Reefs of American Samoa: A Story of Hope | Smithsonian Ocean". ocean.si.edu. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ "American Samoa". National Marine Sanctuary Foundation. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Rapid Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Strategies for the National Marine Sanctuary and Territory of American Samoa" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae "Climate Change Impacts National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa" (PDF).

- ^ "Crustose coralline algae and sedimentation | eAtlas". eatlas.org.au. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- ^ a b c d "American Samoa Coral Reefs: Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment Summary" (PDF).

- ^ "2007-2020 NMSAS Condition Report | Office of National Marine Sanctuaries". sanctuaries.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ "National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa" (PDF).

- ^ "Diving National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa's Big Momma • Scuba Diver Life". 7 March 2018.

- ^ "Big Momma | Office of National Marine Sanctuaries".

- ^ a b "Big Momma coral head at Fagatele Bay".

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch