Naxos (Sicily)

Νάξος | |

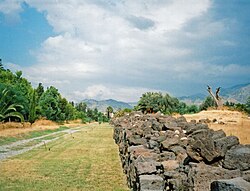

Walls of Naxos | |

| Location | Giardini Naxos, Province of Messina, Sicily, Italy |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°49′23″N 15°16′24″E / 37.82306°N 15.27333°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Chalcidean colonists |

| Founded | 734 BC |

| Periods | Archaic Greece to Classical Greece |

Naxos or Naxus (Ancient Greek: Νάξος) was an ancient Greek city of Magna Graecia, presently situated in modern Giardini Naxos near Taormina on the east coast of Sicily.

Much of the site has never been built on and parts have been excavated in recent years.

Its remains are open to the public and an on-site museum contains many finds.

Location

[edit]The city occupied a low rocky headland, now called Cape Schisò, formed by an ancient lava flow, immediately to the north of the Acesines (modern Alcantara) stream.

Name

[edit]

There can be little doubt that the name was derived[1] from the origin of the first colonists from Naxos in Greece.[2] This has become even more definite since 1977 when the marble cippus (or sacred stone) inscribed with a dedication to the goddess Enyo was found in the large sanctuary west of the Santa Venera river. The characters are written in the unique 7th c. BC script of Greek Naxos.[3]

History

[edit]Foundation

[edit]Ancient writers agree that Naxos was the most ancient of all the Greek colonies in Sicily;[4][5] it was founded in 734/5 BC, a year before Syracusae, by colonists from Naxos[1] in Greece and Chalcis in Euboea, with whom were mingled, according to Ephorus, a number of Ionians. He also named Theocles, or Thucles as leader of the colony and founder of the city and as an Athenian by birth; but Thucydides takes no notice of this, and describes the city as a purely Chalcidic colony; and it seems certain that in later times it was generally so regarded.[6] The memory of Naxos as the earliest of all the Greek settlements in Sicily was preserved by the dedication of an altar outside the town to Apollo Archegetes, the divine patron under whose authority the colony had sailed; and it was a custom (still retained long after the destruction of Naxos itself) that all Theori or envoys proceeding on sacred missions to Greece, or returning from thence to Sicily, should offer sacrifice on this altar.[7]

The new colony must have been speedily joined by fresh settlers from Greece, as within six years after its first establishment the Chalcidians at Naxos were able to send out a fresh colony, which founded the city of Leontini (modern Lentini) in 730 BC; and this was speedily followed by that of Catana. Theocles himself became the Oekist, or recognised founder, of the former and Euarchus, probably a Chalcidic citizen, of the latter.[8] Strabo and Scymnus Chius both represent Zancle (modern Messina) also as a colony from Naxos, but no allusion to this is found in Thucydides. But, as it was certainly a Chalcidic colony, it is probable that some settlers from Naxos joined those from the parent country.[9] Callipolis was a colony of Naxos and also ceased to exist at an early period.[10] Notwithstanding this evidence of its early prosperity, there is very little information as to the early history of Naxos.[11] Archaeology shows that the city walls were built in the mid 6th c. BC.

5th century BC

[edit]The 5th century BC was very turbulent for the city as confirmed by the archaeological record. It was one of the cities besieged and taken by Hippocrates, despot of Gela, in 492/1 BC.[12] It passed under the authority of Gelon of Syracuse then his brother Hieron in 476 BC.[citation needed] Hieron, with a view to strengthen his own power, removed the inhabitants of Naxos at the same time with those of Catana, and settled them together at Leontini, while he repeopled the two cities with fresh colonists from other quarters.[13] The city was completely rebuilt in about 470 BC probably by Hieron. The new classical town grid was preceded by a systematic levelling of the archaic buildings: excavations have found two superimposed urban layouts.[14]

The name of Naxos is not specifically mentioned during the revolutions that ensued in Sicily after the death of Hieron; but there seems no doubt that the city was restored to the old Chalcidic citizens at the same time as these were reinstated at Catana, 461 BC;[15] and hence we find, during the ensuing period, the three Chalcidic cities, Naxos, Leontini, and Catana, generally united by the bonds of amity, and maintaining a close alliance, as opposed to Syracuse and the other Doric cities of Sicily[16] Thus, in 427 BC, when the Leontini were hard pressed by their neighbours of Syracuse, their Chalcidic brethren afforded them all the assistance in their power;[17] and when the first Athenian expedition arrived in Sicily under Laches and Charoeades, the Naxians immediately joined their alliance. With them, as well as with the Rhegians on the opposite side of the straits, it is probable that enmity to their neighbours at Messana was a strong motive in inducing them to join the Athenians; during the hostilities that ensued, the Messanians having on one occasion, in 425 BC, made a sudden attack upon Naxos both by land and sea, the Naxians vigorously repulsed them, and in their turn inflicted heavy loss on the assailants.[18] Naxos never recovered from this blow.

For the great Athenian expedition to Sicily (415 BC), the Naxians immediately announced their alliance, even though their related cities of Rhegium (modern Reggio di Calabria) and Catana held aloof; they not only furnished the Athenians with supplies, but received them freely into their city.[19] Hence it was at Naxos that the Athenian fleet first touched after crossing the straits; and at a later period the Naxians and Catanaeans are enumerated by Thucydides as the only Greek cities in Sicily which sided with the Athenians.[20] After the failure of this expedition the Chalcidic cities were naturally involved for a time in hostilities with Syracuse; but these were suspended in 409 BC, by the danger which seemed to threaten all the Greek cities alike from the Carthaginians.[21] Their position on this occasion preserved the Naxians from the fate which befell Agrigentum (modern Agrigento), Gela, and Camarina; but they did not long enjoy this immunity. In 403 BC, Dionysius of Syracuse, deeming himself secure from the power of Carthage as well as from domestic sedition, determined to turn his arms against the Chalcidic cities of Sicily; and having made himself master of Naxos by the treachery of their general Procles, he sold all the inhabitants as slaves and destroyed both the walls and buildings of the city, while he bestowed its territory upon the neighbouring Siculi.[22]

Tauromenium

[edit]The Siculi soon formed a new settlement on the nearby Mount Taurus and this gradually grew up into the city of Tauromenium, (modern Taormina).[23] This took place about 396 BC and the Siculi were still in possession of this stronghold some years later.[24] Meanwhile, the exiled inhabitants of Naxos and Catana formed a considerable body that kept together. An attempt was made in 394 BC by the Rhegians to settle them again at Mylae (modern Milazzo), but without success for they were expelled by the Messanians and from this time appear to have been dispersed in various parts of Sicily.[25] In 358 BC Andromachus, the father of the historian Timaeus, collected the Naxian exiles together again from all parts of the island and established them at Tauromenium which became the successor of the ancient Naxos.[26] Hence Pliny the Elder speaks of Tauromenium as having been formerly called Naxos which is not strictly correct.[27] The new city quickly rose in importance. The site of Naxos itself seems to have been never again inhabited in antiquity; but the altar and shrine of Apollo Archegetes continued to mark the spot where it had stood, and are mentioned in the war between Octavian and Sextus Pompey in Sicily, 36 BC.[28]

Roman

[edit]Some late Roman construction over the Greek ruins includes a mansio and streets found on the bedrock continuing the general line of the ancient stenopos.[29]

The site

[edit]

The city walls are visible on the south of the site and were built in the mid 6th c. BC using the Cyclopean polygonal technique. They were up to 8 m high with the first 2 m of stone and the higher layer of mud bricks.

The city was completely rebuilt in about 470 BC probably by Hieron I of Syracuse with a new Hippodamian orthogonal street plan on a different orientation from the first city.[30] The original city was razed and lies below the later one. Only the sacred precincts, some temples and the shipyard were left intact on a different orientation. The city plan represents one of the best preserved western examples of its type. Square bases, perhaps altars, mark each crossroads on its south east corner.

The seafront façade of the shipyard complex indicates that the present sandy beachfront is circa 180–190 m further out from the 5th century BC the coastline and that the sea level was about 2 m higher than at present.

Coinage

[edit]The coins of Naxos, which are of fine workmanship, may almost all be referred to the period from 460 BC to 403 BC, which was probably the most flourishing in the history of the city.

- Tetradrachm minted in Naxos from the 5th century BC.[31]

- Greek Silver Tetradrachm of Naxos (Sicily)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Hellanicus FGrH 4 F82

- ^ Apud Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Χαλκίς

- ^ Panhellenes at Methone: Jenny Strauss Clay, Irad Malkin, Yannis Z. Tzifopoulos, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co, p 168

- ^ Hellanicus FGrH4 F82

- ^ Thucydides VI.3.1.

- ^ Thucydides vi.3; Ephor. apud Strabo vi. p. 267; Scymn. Ch. 270-77; Diodorus Siculus xiv.88. Concerning the date of its foundation see Clinton, F. H. vol. i. p. 164; Eusebius Chron. ad 01. 11. 1.

- ^ Thucydides vi.3; Appian, B.C. v. 109.

- ^ Thucydides vi.3; Scymn. Ch. 283-86; Strabo vi. p. 268.

- ^ Strabo vi. p. 268; Scymn. Ch. 286; Thucydides vi. 4.

- ^ Strabo vi. p. 272; Scymn. Ch. 286

- ^ Lentini, M. C., & Whitbread, I. K. (2012). RECENT INVESTIGATION OF THE EARLY SETTLEMENT LEVELS AT SICILIAN NAXOS. Mediterranean Archaeology, 25, 309–315. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24653576

- ^ Herodotus vii.154

- ^ Diodorus xi.49

- ^ M. Lentini, Naxos of Sicily in the 5th century BC: New Research, GREEK COLONISATION New Data, Current Approaches, Proceedings of the Scientific Meeting held in Thessaloniki (6 February 2015)

- ^ Diodorus xi.76

- ^ Diodorus xiii.56, xiv.14; Thucydides iii.86, iv.25

- ^ Thucydides iii.86

- ^ Thucydides iv.25

- ^ Diodorus xiii.4; Thucydides vi. 50

- ^ Thucydides vii. 57

- ^ Diodorus xiii.56

- ^ Diodorus xiv.14, 15, 66, 68

- ^ Diodoros xiv.58, 59

- ^ Diodorus xiv.88

- ^ Diodoros xiv. 87

- ^ Diodorus xvi.7

- ^ Pliny, N.H. iii. 8. s. 14

- ^ Appian, B.C. v. 109

- ^ Pelagatti P., ‘Nasso: storia della ricerca archeologica’, Bibliografia Topografica della Colonizzazione, Greca in Italia, xii (Pisa and Rome),1993, 268–312

- ^ Pelagatti 1976-1977: P. Pelagatti, “L’attività del- la Soprintendenza alle Antichità della Sicilia Orientale”, Kokalos 22-23, 519-550.

- ^ a b Sear, David R. (1978). Greek Coins and Their Values . Volume I: Europe (pp. 76 coin #727 and pp. 91, coin # 872). Seaby Ltd., London. ISBN 0 900652 46 2

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Naxos". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Naxos". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch

![Tetradrachm minted in Naxos from the 5th century BC.[31]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/Dionysos_tetradrachm_Naxos.JPG/960px-Dionysos_tetradrachm_Naxos.JPG)

![Drachm minted in Naxos from the 6th century BC.[31]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8a/Naxos-02.jpg/619px-Naxos-02.jpg)