New York Savings Bank Building

New York Savings Bank | |

New York City Landmark No. 1634, 1635 | |

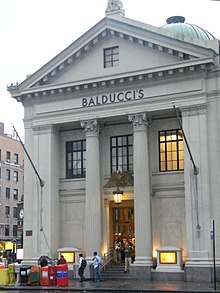

New York Savings Bank in 2019 | |

| |

| Location | 81 Eighth Avenue, New York, New York |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°44′24″N 74°00′09.4″W / 40.74000°N 74.002611°W |

| Built | 1896 |

| Architect | R. H. Robertson; George H. Provot |

| Architectural style | Classical Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 99001657[1] |

| NYCL No. | 1634, 1635 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | January 7, 2000 |

| Designated NYCL | June 8, 1988 |

The New York Savings Bank Building is a former bank building in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. Constructed for the defunct New York Savings Bank from 1896 to 1898, it occupies an L-shaped site on 81 Eighth Avenue, at the northwestern corner with 14th Street. The New York Savings Bank Building was designed by Robert Henderson Robertson, with later additions by George H. Provot and Halsey, McCormack & Helmer. The building's facade and interior are New York City designated landmarks, and the building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The building's basement contains a granite water table, while the rest of the facade is clad with Vermont marble. The main entrance is through a portico on Eighth Avenue with Corinthian columns and a triangular pediment. The 14th Street facade is wider than the Eighth Avenue facade and is divided asymmetrically into three sections; the center section is topped by a pediment. Most of the building is topped by a gable roof with copper cladding, although the building also contains a dome with clerestory windows. The main feature of the interior is a triple-height banking room with a vaulted, coffered ceiling; the dome is recessed within the center of the ceiling.

The New York Savings Bank was founded in 1854 and relocated to Eighth Avenue and 14th Street in 1857. The current building was constructed in two stages, allowing the bank to continue doing business without interruption; the building was finished by 1898. As the New York Savings Bank continued to expand, Provot redesigned the main facade on Eighth Avenue in 1930. Halsey, McCormack & Helmer designed a northward annex that opened in 1942 and was demolished in 1972. Following mergers in the late 20th century, the building became a branch of the New York Bank for Savings, then the Buffalo Savings Bank, which moved out of the building in 1987. After standing vacant for several years, the building reopened in 1994 as a branch of Central Carpet. The building was a Balducci's food market from 2005 to 2009 and had become a CVS Pharmacy by the 2010s.

Site

[edit]The New York Savings Bank Building is located at 81 Eighth Avenue, at the northwest corner with 14th Street, in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City.[2] The land lot covers 8,556 square feet (794.9 m2) and is L-shaped; its western section extends further into the city block than the eastern section.[2] The building has frontage of 45.25 ft (13.79 m) on Eighth Avenue and 125 ft (38 m) on 14th Street,[2] and it measures 146 ft (45 m) long along its southern lot line. The New York Savings Bank Building is near the New York County National Bank Building to the south and 111 Eighth Avenue to the north;[2] in addition, an entrance to the New York City Subway's 14th Street/Eighth Avenue station is directly outside the building.[3] The New York Savings Bank Building is one of several bank buildings that had been erected around 14th Street by the early 20th century.[4][5]

Architecture

[edit]The New York Savings Bank Building, completed in 1897, was originally designed in the neoclassical style by Robert Henderson Robertson.[6][7] The exterior of the building features porticos and a dome inspired by those of ancient Roman temples, while the interior has an expansive vaulted ceiling that was intended to attract depositors.[8] George H. Provot modified the main entrance in 1930, while the firm of Halsey, McCormack & Helmer designed a now-demolished annex to the north in 1940.[8][9]

Facade

[edit]The New York Savings Bank Building retains much of its original design.[10] The 14th Street and Eighth Avenue elevations of the facade are largely clad with Vermont marble and ashlar, although the water table at the base is clad with of polished granite.[10][11] The marble ashlar cladding is about 4 inches (100 mm) thick, behind which are exterior brick walls laid in cement-and-lime mortar. The walls are freestanding, rather than party walls, and contain bluestone coping. The building's foundation extends 15 ft (4.6 m) beneath the curb.[12] An entablature wraps around both elevations, and a dome is placed asymmetrically above the roof.[10]

Eighth Avenue

[edit]

The building's main entrance is along its narrower frontage on Eighth Avenue, where there is a triple-height portico in the Corinthian order. The portico is divided vertically into three bays, with two fluted columns on the inside and a pair of paneled pilasters with antae on the outside. These support an entablature and a triangular pediment.[10][11] The columns have Corinthian capitals, while the antae are topped by egg-and-dart moldings and anthemia.[10] On the entablature above the columns and pilasters, the name "The New York Savings Bank" was originally spelled in bronze letters. There is a small window inside the pediment, as well as a recessed limestone acroterion on the parapet atop the pediment.[13]

The facade on Eighth Avenue is recessed behind the columns In the center bay, between the fluted columns, is a stoop that ascends to the building's main entrance. The entrance doorway is flanked by Doric pilasters, which support a cornice that stretches horizontally above the first floor.[10][11] Initially, there were four doors on Eighth Avenue—depositors entered through the two inner doors and exited through the two outer doors—but these were removed in 1930.[14] A bronze eagle is placed on the cornice above the doorway, and an eight-sided lantern is suspended from the eagle's mouth.[10] The two outer bays of the first story, situated on either side of the entrance, feature blind panels instead of windows.[10][11] In front of these blind panels are stone pedestals with vitrines; these pedestals originally contained bronze lanterns.[10] On the second story are three rectangular windows, one in each bay. A belt course with anthemia runs above the second-story windows.[10][11]

14th Street

[edit]Because of its internal layout, the 14th Street elevation is asymmetrical and divided vertically into three sections. The western and middle sections each have three double-height rectangular window openings, while the eastern section is windowless.[11][13] A pediment and the building's dome rise above the center of the middle section.[11][13][15] The presence of the pediment and dome were intended as an allusion to the large banking room inside.[15] Above all three sections is a entablature, as well as a copper cresting stretching across much of the facade.[16]

The middle section is arranged similarly to the portico on Eighth Avenue. It is divided into three bays, each of which has a rectangular window opening framed by rosettes. Each bay contains a horizontal transom bar, with Greek-key patterns and lions' heads, which separates a smaller pane on the second floor and a larger pane on the first floor. Beneath each window sill are guttae, while above each window is an ornate architrave with molded water leaf motifs and raised circles. The bays are flanked by four pilasters, which support a pediment at the third story. The tops of the pilasters are decorated with egg-and-dart moldings and anthemia, and the outermost two pilasters contain paneling. Above the pilasters is an entablature, which originally had the bank's name in bronze letters. The entablature is capped by a pediment, which contains an opening with a bronze grille.[13]

The eastern section is a plain marble-and-ashlar wall without window openings. A sign with a clock is attached to the facade near the corner of 14th Street and Eighth Avenue. This sign is triangular with a pair of clock faces.[11][13] Each clock face is flanked by twisting colonnettes that support a horizontal molding, and a vitrine is placed below each clock face. Atop the sign is a carved beehive, the symbol of the New York Savings Bank.[13] Within the western section are three double-height rectangular window openings, each of which has a transom bar and an ornate architrave, similar to those in the middle section.[11][13] The windows in the western section are slightly narrower than those in the middle section, and there are subtle differences in the Greek-key motifs on each transom bar and the rosettes surrounding each window. Each window has a jamb with a repeating pattern, composed of two palmettes flanking a rosette.[13] Beneath the western section's westernmost window, a flight of six steps leads to a rear doorway, topped by a lintel with acroteria.[17]

Roof

[edit]The building's banking room along 14th Street has a gabled roof, which is made of terracotta brick above steel rafters and is covered with copper sheeting.[16] The gabled roof is made of 12-inch-thick (30 cm) steel, cast in pieces weighing 40 lb (18 kg).[12]

Above the gabled roof is a copper domed roof.[7][11][16] The domed roof is divided horizontally into three sections. The lowest section is the parapet, which consists of a pair of crescents (one each to the north and south), formed by the intersection of the sloping gables below and the clerestory above. The parapet is clad with copper sheeting with multiple seams.[16] The second section is the clerestory, which contains 20 rectangular windows made of stained glass. Each window is separated by pilasters, which contain a rosette flanked by anthemia. Above the clerestory is an entablature with a frieze containing embossed disks, lions' heads, a bead molding on its lower border, and an egg-and-dart molding on its upper border.[16] The highest section is the dome itself, which is clad with copper and is plain in design except for vertical battens. A flat circular finial with anthemia and lions' heads rises above the dome. There are catwalks surrounding the dome anda set of stepladders leading to the catwalk.[16]

Interior

[edit]Although the roof is three stories high, the interior is split into varying levels, ranging from one to three stories, with several areas incorporating triple-height spaces.[10] Siena marble was used extensively inside the building.[7][18] Robertson placed public rooms along the southern and eastern ends of the L-shaped site, facing Eighth Avenue, while the northern end contained offices for bank officials such as tellers, officers, and clerks. The main feature of the interior was the banking room accessed from Eighth Avenue.[19]

Banking room

[edit]

The former banking room is a rectangular space with a high ceiling. The walls are wainscoted in Siena marble and contain engaged Corinthian columns, pilasters, and plinths of the same material.[11][20][21] The capitals of the columns, the entablatures atop the walls, and the vaulted ceiling are made of plaster. Most of the wall surfaces above the marble wainscoting were covered with travertine in a 1930 renovation.[11][20] The banking room has a rose-gray marble floor.[20][21] An L-shaped beige-marble tellers' counter was placed about 15 ft (4.6 m) away from the west and south walls.[20] This counter had been removed by the 1990s.[22] The banking room's ceiling is coffered and contains a transverse rib, which is supported by an engaged column on the north and south walls.[23][24] This creates a proscenium-like arch that divides the room into western and eastern sections, indicating how the public areas were originally separated from the staff areas.[23] The center of the ceiling contains a small dome.[24]

The south wall is clad with travertine above a marble wainscoting and is divided asymmetrically by an engaged column. The eastern (left) section of the south wall contains three rectangular windows with bronze frames, flanked by four marble pilasters atop marble plinths. The western (right) section is similar in design but is narrower.[24] The west wall is also clad with travertine above marble and is decorated only with a circular bronze clock face, inset within a square. The spandrels at each corner of the square contain anthemia, and the clock hands and Roman numerals are attached to the travertine wall.[25] The northwestern corner of the building contains some of the original wainscoting.[26] The north wall is divided asymmetrically by an engaged column, but some of the pilasters and wainscoting were removed during successive renovations.[25] The east wall originally contained four doorways, which were consolidated into one doorway in 1930 and redesigned in a Moderne style in 1952. Above the doorway are four windows, marble pilasters, architraves, sills, and an entablature, dating from the original design.[24]

Each of the ceiling's coffers features an embossed rosette at its center, surrounded by an inner egg-and-dart molding and an outer waterleaf molding.[25] The coffers have been repainted several times over the years.[22] Above the center of the room's western half is a dome, which rests on a tholobate. The bottom of the tholobate contains a Greek key pattern with lions' heads and an egg-and-dart molding above.[25] The surface of the tholobate contains 20 short fluted pilasters, with a square stained glass window between each set of pilasters. Beneath each stained-glass window are four square classical-style cast iron grilles, above which is an anthemion.[25][26] An entablature with egg-and-dart molding runs above the tholobate's pilasters.[25] The dome itself is divided into coffers with rosettes, similar to the main ceiling, and is topped by a large central rosette.[26][27][a] A bronze chandelier, with etched glass panels and eagle-shaped finials, hangs from the central rosette. Two similar chandeliers hang from the main ceiling.[26]

History

[edit]Use as bank

[edit]The current building was constructed for the New York Savings Bank,[28][29] which was chartered on April 17, 1854, as the Rose Hill Savings Bank.[30][31] The bank's original headquarters was at the intersection of Third Avenue and 21st Street on the East Side of Manhattan.[28][29] In 1857, the Rose Hill Savings Bank moved to the northwest corner of Eighth Avenue and 14th Street, occupying the basement of a four-story structure built for the New York County Bank.[29] The Rose Hill Savings Bank became the New York Savings Bank in 1862.[32] Development began to spread northward from Lower Manhattan to 14th Street after the American Civil War, and the New York Savings Bank correspondingly saw a large increase in business. The bank eventually purchased its building outright and moved to the first floor.[29]

Development and early years

[edit]By June 1896, the New York Savings Bank had hired R. H. Robertson to design a replacement for the bank's existing building.[33][34] The bank received a construction permit that month; records show that Otto M. Eidlitz was the mason and that S. W. McGuire was the carpenter.[34] Although one source characterized the structure as being a four-story brick structure,[35] it was ultimately made of marble.[10][11] The edifice was planned to cost $220,000.[35] The new building was erected in two phases, allowing the bank to continue operating; the administrative offices to the west were finished first, while the public rooms to the east were completed afterward.[14] In March 1897, the bank applied to the New York City Department of Buildings (DOB) for a permit to construct a temporary entrance to the western section of the new building.[34] The bank requested the city government's permission to add temporary flooring that April.[22]

After the western section was completed in May 1897, depositors used a staircase to access a temporary entrance to the western section.[14] That October, the bank filed another revised plan, this time proposing an I-beam under the banking room's floor.[22] The banking room and the entrance from Eighth Avenue was completed by 1898.[14][18] The new building was to advertise the bank's presence to customers in Chelsea and Greenwich Village, as well as those working in the nearby Meatpacking District and on the Hudson River shoreline.[28] The bank's original tellers' counter was U-shaped and was placed in the center of the room. Because of the counter's layout, customers had to enter the building through the two center doorways on Eighth Avenue and exited via the two outer doorways.[14] By 1900, the New York Savings Bank had nearly $18 million in deposits (equal to about $659 million in 2023);[36] this amount had grown to $47 million by 1920 (equal to about $715 million in 2023).[37]

1910s to 1940s additions

[edit]

When the adjacent segment of 14th Street was widened in 1913, architect Alexander McMillan Welch submitted plans to the DOB for a modification of the coal bunker under the sidewalk of 14th Street.[38][34] The work cost an estimated $3,000.[38] The bank added a sign with a clock on 14th Street in 1926.[34] The neighborhood was growing by the 1920s, with the development of many structures and the Independent Subway System's Eighth Avenue Line on the adjacent stretch of Eighth Avenue.[39]

The Eighth Avenue facade was significantly modified in 1930, when the original stairs, which projected onto the sidewalk, were replaced with a narrower, recessed flight of stairs. In conjunction with the staircase replacement, the four original doorways were replaced with a single door.[8][34] Also on Eighth Avenue, the bank installed a new facade in front of the original, deeply recessed facade.[34] This allowed the bank to install a new entrance vestibule clad in marble, as well as customer restrooms, between the old and new facades.[40] These modifications were designed by George Provot, a onetime partner of Alexander McMillan Welch.[8][41] Later in 1930, the bank submitted plans to the DOB for a recessed entrance to the basement on 14th Street.[34] The New York Savings Bank added a deposit box for nighttime deposits in 1931; at the time, it was New York City's only "night depository".[42]

The New York state government authorized the New York Savings Bank to sell life insurance policies starting in January 1939.[43][44] To accommodate its expanded operations, the New York Savings Bank hired Adolf L. Muller[b] of Halsey, McCormack & Helmer in 1940 to design a limestone-faced annex[21] north of the building.[8][45] Muller submitted plans for the annex to the DOB in November 1940, and workers began razing a pair of four-story buildings at 85 and 87 Eighth Avenue the next month.[45] The project involved cutting a hole into the northern wall of the banking room; removing the officers' counter at the western end of that room; and replacing the original U-shaped tellers' counter with an L-shaped counter.[40] Construction was delayed by more than eight months due to labor and material shortages during World War II.[46] The annex opened on April 17, 1942, the 88th anniversary of the bank's founding.[46][47] When the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation began insuring the New York Savings Bank's depositors the same year,[48][49] the bank had $83.976 million in deposits (equal to about $1,566 million in 2023).[50] The facade was washed in 1945, and a canopy above the adjacent subway entrance was approved at the same time.[51]

Mid- and late 20th century

[edit]

The bank acquired a lot at 89 Eighth Avenue next to the bank building's annex in November 1952.[52] The same month, Muller filed plans to remove the restrooms, replace the entrance vestibule, and reconfigure the northern portion of the banking room. The renovations included space for a paying and receiving unit and check-writing desks on the first floor; space for real estate department on the second floor; and new travertine pilasters, tellers' screens, and bronze rails.[40] The New York Savings Bank installed a closed-circuit system in 1953 to verify customers' accounts and signatures on checks.[53][54] The system was expected to halve withdrawal times;[54] The New York Times described it as "the nation's first regular use of television in the banking field".[53] The bank opened its first branch at Rockefeller Center later the same year, retaining the Eighth Avenue building as its main office;[55] a second branch opened in 1959.[56]

The New York Savings Bank was absorbed by the larger Bank for Savings in August 1963, becoming the New York Bank for Savings.[57][58] The merger allowed the combined bank to open more branches,[c] and the Eighth Avenue building became one of the New York Bank for Savings' eight branches.[58][60] The bank filed plans in 1964 for the replacement of the sign on the 14th Street facade, and these plans were approved shortly afterward. The New York Bank for Savings also filed plans in 1971 to replace the bank building's annex and several adjoining lots with single-family houses, but this was never carried out.[51] Instead, the bank filed plans for a six-story apartment building at 85 Eighth Avenue[18] on the site of the annex.[8][51] The annex was demolished in 1972, and the openings on the north wall of the banking room were covered with travertine.[8][61] The bank also filed plans for an illuminated sign on the bank building's facade.[51]

By 1981, the New York Bank for Savings was struggling financially.[62] The New York Bank for Savings merged with the Buffalo Savings Bank the next year, and the building became a branch of the Buffalo Savings Bank.[63] A company named Landmark Realty acquired the building in 1982 but continued to lease space to the bank.[18] During the 1980s, the bank was colloquially known as the Goldome;[18] this nickname was derived from the gold dome of the Buffalo Savings Bank's own headquarters in Buffalo, New York.[12] The Buffalo Savings Bank moved out of the building in July 1987,[64] and the structure remained vacant for several years.[65][66]

Post-bank use

[edit]After the Buffalo Savings Bank relocated, Landmark Realty initially said it had no plans for the building.[18] However, documents filed in May 1987 indicated that a 32-story residential tower could be erected on the bank's site using air rights from the building at 85 Eighth Avenue.[64] By mid-1987, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) considered designating the building's facade and its interior as city landmarks. The LPC notified Landmark Realty of an upcoming landmark hearing on July 14, 1987. Three days later, Landmark Realty removed some of the stained-glass windows and bronze decorations,[18] prompting a member of a local preservation group to say that the building "has been vandalized by the owner".[64] A hole in the roof prompted concerns that the interior could also be damaged.[64] The facade and interior of the building were protected as city landmarks in June 1988.[67]

Use as Central Carpet store

[edit]The Wiener family, who owned the building in the early 1990s, was looking to rent out the property, having canceled their plans to demolish or sell it.[66] Carpet store Central Carpet bought the building in 1992, with plans to renovate it into the company's second store.[68] The firm had acquired the New York Savings Bank Building because of the site's proximity to other carpet stores.[65][69] Central Carpet's owner Ike Timianko had been searching for store locations for seven years before seeing the former bank building while driving through the neighborhood. Timianko encountered difficulties in obtaining financing for the renovation because his longtime bank was pessimistic about the neighborhood.[65] The company renovated the building and added a mezzanine above the banking hall; the renovation was designed by Scarano, Englert & Norton. Because workers had to follow preservation regulations, the cost of the renovation ultimately increased to $8 million.[65] The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) had proposed erecting a subway entrance outside the New York Savings Bank Building's main entrance. After Central Carpet indicated that it might not move into the building, the MTA clarified that the subway entrance would not block the building's entrance.[3]

The Central Carpet store opened in October 1994.[65][68] At the time of its opening, the store was advertised as "The Grand Palais of Rugs" and exhibited over 15,000 rugs.[65][70] The president of the Preservation League of New York State said the bank building's conversion into a carpet store was "better than being demolished".[71] The adjoining stretch of Eighth Avenue had been rundown when Central Carpet opened its store at 81 Eighth Avenue, but upscale stores had begun relocating to the neighborhood by the late 1990s, spurred by the carpet store's opening. The success of the Central Carpet store in the former bank building prompted Timianko to close his original location on the Upper West Side.[72] The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 7, 2000.[1]

Later use

[edit]

Businessman Mark Ordan announced in 2004 that he would open a Balducci's gourmet market on two floors of 81 Eighth Avenue, which was still occupied by Central Carpet at the time. In addition, Ordan would convert 8,000 sq ft (740 m2) into kitchens, offices, and storage space.[73] The store at Eighth Avenue, dubbed the "Temple of Food",[74] would have been the flagship of a chain of Balducci's stores.[75] Balducci's proposed removing an interior partition dating from 1952, as well as rebuilding a set of entrances on Eighth Avenue that had been destroyed in 1930; the latter modification would make the building accessible to disabled customers. The LPC approved these changes in February 2005.[76] The Balducci's market at 81 Eighth Avenue opened in December 2005[77] and closed suddenly in April 2009 following a company-wide "restructuring".[78][79] Since the 2010s, the bank building has been used as a CVS Pharmacy location.[80]

Impact

[edit]When the bank building was constructed, the New-York Tribune wrote: "The building stands out with especial prominence in its neighborhood, which is not remarkable for beauty of architecture."[18] By contrast, Montgomery Schuyler wrote for the Architectural Record in 1896 that he believed the building's design was unbalanced.[18][81] Schuyler wrote: "The portico, taken by itself, is an 'example', but the longer side lacks not only formal symmetry, but artistic balance, and the skylighted dome does not so dominate the building as to account for and justify the transeptual arrangement. It is pretty evidently either too important or not important enough."[81][d]

In 2000, a writer for The New York Times called the New York Savings Bank Building a "far more ornate edition of the genre" of neighborhood savings banks, "with its domed copper roof and pillared hall".[82] After the Balducci's market opened, a writer for New York magazine described it as "stately and grand, as only an 1897 New York Savings Bank building turned 21st-century food hall can be."[83] Architectural writer Andrew Dolkart and the LPC described the building in 2009 as "an early example of Classical Revival bank design".[7] The historian Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel wrote in 2011 that the building was "a fine example of the classical style popularized by the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago".[67]

See also

[edit]- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The lowest tier of coffers is surrounded by egg-and-dart and waterleaf moldings, while the other tiers are surrounded only by egg-and-dart moldings.[27]

- ^ Sometimes spelled Miller[8]

- ^ Savings banks in New York are typically limited to five branches, but savings banks created from the merger of multiple banks can have as many branches as their predecessors did. The New York Bank for Savings was allowed to have 10 branches, and the bank's tenth branch opened in 1966.[59]

- ^ Schuyler's review (Schuyler 1896, p. 208) incorrectly characterizes the building as being on Ninth Avenue. A drawing of the building (Schuyler 1896, p. 211) explicitly describes it as the New York Savings Bank on Eighth Avenue and 14th Street.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places 2000 Weekly Lists" (PDF). National Park Service. 2000. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "81 8 Avenue, 10011". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Howe, Marvine (July 10, 1994). "Neighborhood Report: the Villages; Would 15th Street Be Lost for Lack of a Subway Entrance?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Jacobson, Aileen (November 20, 2019). "14th Street, Manhattan: A Congested Thoroughfare Transformed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ "Fourteenth St. Is Becoming Bank Center: Residential and Business Activity Are Attracting Financial Institutions". New York Herald Tribune. November 24, 1929. p. E1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1111986647.

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c d New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h National Park Service 2000, p. 8.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m National Park Service 2000, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 4.

- ^ a b Diamonstein-Spielvogel 2011, pp. 365–366.

- ^ a b c d e f Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 7.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gray, Christopher (September 13, 1987). "Streetscapes: The New York Savings Bank; Landmark Hearing for 14th St. Building". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1988, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1988, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Diamonstein-Spielvogel 2011, p. 366.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1988, p. 25.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2000, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1988, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1988, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service 2000, p. 4.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1988, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2000, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 1.

- ^ Paine, W.S. (1889). The Laws of the State of New York Relating to Banks, Banking and Trust Companies, and Companies Receiving Money on Deposit: Also the National Bank Act and Cognate United States Statutes, with Annotations. Banks & Bros. p. 551. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Stevens, Frederic Bliss (1915). History of the Savings Banks Association of the State of New York, 1894-1914. N.Y., Doubleday, Page. p. 574. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Valentine, David Thomas (1862). A Compilation of the Laws of the State of New York, Relating Particularly to the City of New York ... Common Council. p. 190. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Building News". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 57, no. 1474. June 13, 1896. p. 1017. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 11.

- ^ a b "Possible Contracts". Electrical Age. Vol. 18, no. 4. July 25, 1896. p. 419. ProQuest 753956477.

- ^ "State Savings Banks; Condition of Savings Institutions in New York and Vicinity on Jan. 1, 1900". The New York Times. January 31, 1900. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 5, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ "New York Savings Bank Deposits Increase: Twenty-eight New York City Institutions Show $1,184,424,384 Deposits, an Increase of $95,275,052 in Year". The Wall Street Journal. August 25, 1920. p. 8. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 129844708.

- ^ a b "Plans Filed—Alterations—Manhattan". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 92, no. 2366. July 19, 1913. p. 154. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Eighth Av. Section Builds for Future: Substantial Character of New Construction Will Have Lasting Effect on District". The New York Times. January 1, 1928. p. RE1. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 104707027.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1988, p. 26.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 3.

- ^ "New York Savings Bank Installs Night Depository". Bankers' Magazine. Vol. 123, no. 2. August 1931. p. 180. ProQuest 124373718.

- ^ "New York Savings Bank Speeds Insurance Sales". New York Herald Tribune. January 7, 1939. p. 22. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1322400426.

- ^ "Bank Has $5,000,000 in Life Policies Out; New York Savings Reports 6,400 Persons Are Insured". The New York Times. June 14, 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b "Bank Opens New Wing; New York Savings Also Marks Founding Anniversary". The New York Times. April 17, 1942. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ "Banks and Bankers: On the State Association Front". The Wall Street Journal. April 15, 1942. p. 13. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 131386820.

- ^ "N. Y. Banks Join F. D. I. C.: Dollar Savings and New York Savings U. S. Agency Members". New York Herald Tribune. June 23, 1942. p. 27. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1263648251.

- ^ "Bank Deposits Insured; Dollar and New York Savings Get Federal Coverage". The New York Times. June 23, 1942. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ Iyon, W. A. (June 10, 1942). "F.D.I.C. Seen Accepting N.Y. Savings Bank: Other Similar Banks Also Are Believed Ready to Join Federal Agency". New York Herald Tribune. p. 29. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1264507657.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 12.

- ^ "New York Savings Bank Adds to 8th Av. Holding". New York Herald Tribune. November 19, 1952. p. 33. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1320026053.

- ^ a b "Bank Adopting TV in Speed-up Move; New York Savings to Put Plan in Operation at 8th Ave. and 14th St. Office Monday". The New York Times. March 27, 1953. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ a b "Your Account Stars On Television at New York Savings Bank: New System Cuts Withdrawal Time in Half; Use of Electronics Speeds Computation". The Wall Street Journal. March 27, 1953. p. 2. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 132063098.

- ^ "Television Bank' Will Open Today; Closed Circuit to Link Branch to New York Savings' Main Office -- Economies Seen". The New York Times. November 5, 1953. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 12, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ "Bank Moves Toward Automation". The New York Times. March 24, 1959. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ "2 Savings Banks Ready to Merge; F.D.I.C. Approves Plans of the Bank for Savings and New York Savings Question Noted Tabled on Wednesday". The New York Times. August 9, 1963. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ a b "New York Savings Bank And Bank for Savings Plan to Merge Aug. 19: FDIC Approves Creation of Fourth Largest Savings Bank Despite Justice Unit Hostility". The Wall Street Journal. August 12, 1963. p. 8. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 132818867.

- ^ "Bank for Savings Opens Its Tenth Office in City". The New York Times. January 9, 1966. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ Cowen, Edward (December 29, 1963). "How Three Financial Institutions Changed Command; How 3 Financial Institutions Filled Vacuums in Leadership". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1988, p. 27.

- ^ Bennett, Robert A. (November 2, 1981). "The Savings Banks Cushion". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ Gianotti, Peter M. (March 27, 1982). "Business: New York Bank for Savings Merged Into Buffalo Bank". Newsday. p. 12. ISSN 2574-5298. ProQuest 993279415.

- ^ a b c d Neuffer, Elizabeth (July 22, 1987). "New York Halts Removal Work At Former Bank". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 1, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Kamen, Robin (March 20, 1995). "Dealer trying to pull rug out from big foes". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 11, no. 12. p. 3. ProQuest 219170389.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (December 22, 1991). "Commercial Property: Unusual Spaces; An Oak Board Room, Anyone?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 4, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Diamonstein-Spielvogel 2011, p. 365.

- ^ a b "New Yorkers & Co". The New York Times. October 23, 1994. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ "Carpet Store to Open On the Chelsea Fringes". The New York Times. March 20, 1994. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 5, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Slesin, Suzanne (March 30, 1995). "Currents; Wall-to-Wall, If Home Is a Yurt". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Ravo, Nick (August 6, 1995). "Recycling Banks: Some Debits, Some Dividends". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Weintraub, Arlene (April 20, 1998). "No-man's-land no longer". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 14, no. 16. p. 46. ProQuest 219143123.

- ^ Fabricant, Florence (May 23, 2004). "A New Balducci's Is Coming to Manhattan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Rozhon, Tracie (December 1, 2004). "A Big Crowd in the Specialty Niche". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Croghan, Lore (March 25, 2005). "Village Rebirth for Balducci's". New York Daily News. p. 32. ISSN 2692-1251. ProQuest 305949992.

- ^ "Balducci's to return to Greenwich Village". CityLand. March 15, 2005. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Fabricant, Florence (December 14, 2005). "Food Stuff; A New Balducci's, Back Downtown". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Buckley, Cara (April 27, 2009). "Balducci's Makes a Quiet Exit From Manhattan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 11, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Chung, Jen (April 4, 2009). "Bye-Bye, Balducci's: Store Will Close Manhattan Locations". Gothamist. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Chen, Stefanos (April 19, 2019). "Historic Bank Buildings Get a Second Act". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 28, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Schuyler, Montgomery (October–December 1896). "Works of R.H. Robertson" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 6. p. 208. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 13, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Iovine, Julie V. (July 6, 2000). "A House Held Up by a Bank; Renovation yields condos and an aerie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Raisfeld, Robin; Patronite, Robert (March 27, 2006). "Eats Street". New York. Vol. 39, no. 10. pp. 60–61. ProQuest 205146308.

Sources

[edit]- Diamonstein-Spielvogel, Barbaralee (2011). The Landmarks of New York (5th ed.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. pp. 365–366. ISBN 978-1-4384-3769-9.

- Former New York Bank for Savings (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 8, 1988.

- Former New York Bank for Savings Interior (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 21, 1988.

- New York Savings Bank (PDF) (Report). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. January 7, 2000.

External links

[edit] Media related to New York Savings Bank Building at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to New York Savings Bank Building at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch