Nikolaj Velimirović

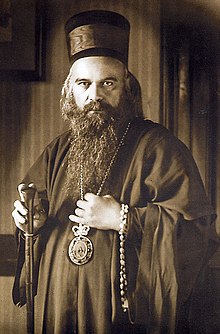

Nikolaj Velimirović Nikolaj of Ohrid and Žiča | |

|---|---|

| |

| Venerable Bishop of Ohrid and Žiča the new Chrysostom | |

| Born | Nikola Velimirović 4 January 1881 Lelić, Serbia |

| Died | 18 March 1956 (aged 75) South Canaan, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Canonized | 24 May 2003 by Holy Synod of the Serbian Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Lelić monastery, Serbia |

| Feast | 3 May (O.S. 20 May)[1][2] |

| Attributes | Episcopal vestments |

Nikolaj Velimirović (Serbian Cyrillic: Николај Велимировић; 4 January 1881 [O.S. 23 December 1880] – 18 March [O.S. 5 March] 1956) was bishop of the eparchies of Ohrid and Žiča (1920–1956) in the Serbian Orthodox Church. An influential theological writer and a highly gifted orator, he was often referred to as the new John Chrysostom[3] and historian Slobodan G. Markovich calls him "one of the most influential bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the twentieth century".[4]

As a young man, he came close to dying of dysentery and decided that he would dedicate his life to God if he survived. He lived and was tonsured as a monk under the name Nikolaj in 1909. He was ordained into the clergy, and quickly became an important leader and spokesman for the Serbian Orthodox Church, especially in its relations with the West. When Nazi Germany occupied Yugoslavia in World War II, Velimirović was imprisoned and eventually taken to Dachau concentration camp. After being released by Germans in December 1944, Velimirović spent time in Slovenia, where he blessed anti-communist volunteers such as Dimitrije Ljotić and other Nazi collaborators. After the war, he moved to the United States in 1946, where he remained until his death in 1956. He strongly supported the unity of all Eastern Orthodox churches and established particularly good relationships with the Anglican and Episcopal Churches.[5]

Nikolaj is held in high regard in the Serbian Orthodox Church and among Serbian right-wing political elite. On 24 May 2003, he was glorified as a saint by the Holy Synod of the Serbian Orthodox Church as Saint Nikolaj of Ohrid and Žiča (Serbian: Свети Николај Охридски и Жички, romanized: Sveti Nikolaj Ohridski i Žički). Many of his views and writings remain controversial. Nikolaj's critics point out to instances of antisemitism in his work, to his admiration of Adolf Hitler and to his links with Ljotić.

Biography

[edit]Childhood

[edit]He was born as Nikola Velimirović in the small village of Lelić, Valjevo in the Principality of Serbia,[6] on the day of the feast of Saint Naum of Ohrid, whose monastery would later be his episcopal see. He was the first of nine children born to Dragomir and Katarina Velimirović (née Filipović), pious farmers. Being very weak, he was baptised soon after his birth in the Ćelije monastery. He was given the name Nikola because Saint Nicholas was the family's patron saint. The first lessons about God, Jesus Christ, the lives of the saints and the holy days of the Church year were provided to him by his mother, who also regularly took him to the Ćelije monastery for prayer and Holy Communion.[7]

Education

[edit]

His formal education also began in the Ćelije monastery and continued in Valjevo. He applied for admission into the Military Academy, but was refused because he didn't pass the physical exam. He was admitted to the Seminary of Saint Sava in Belgrade, where, apart from the standard subjects, he explored a significant number of writings of both Eastern and Western authors, such as Shakespeare, Voltaire, Nietzsche, Marx, Pushkin, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and others.[8] He graduated in 1905.[7]

Nikola had been chosen to become a professor in the Seminary of Saint Sava, but it was decided that he needed to pursue further Eastern Orthodox studies before becoming a teacher. As an outstanding student, he was chosen to continue his studies in Russia and Western Europe. He had a gift for languages and soon possessed a good knowledge of Russian, French and German. He attended the Theological Academy in St. Petersburg and then he went to Switzerland and obtained his doctorate of divinity from the Old Catholic Theological Faculty at the University of Berne with magna cum laude.[7][4]

He received his doctorate in theology in 1908, with the dissertation entitled Faith in the Resurrection of Christ as the Foundation of the Dogmas of the Apostolic Church. This original work was written in German and published in Switzerland in 1910, and later translated into Serbian. The dissertation for his doctor's degree in philosophy was prepared at Oxford and defended in Geneva, in French. The title was Berkeley's Philosophy.

His stay in Britain left an impact on his views and education, which is seen from the fact that he quotes or mentions Charles Dickens, Lord Byron, John Milton, Charles Darwin, Thomas Carlyle, Shakespeare and George Berkeley.[4]

Monastic life

[edit]In the autumn of 1909, Nikola returned home and became seriously ill with dysentery. He decided that if he recovered he would become a monk and devote his life to God. At the end of 1909 his health got better and he was tonsured a monk, receiving the name Nikolaj.[9] He was soon ordained a hieromonk and then elevated to the rank of Archimandrite. In 1910 he was entrusted with a mission to Great Britain in order to gain the co-operation of the Church of England in educating the young students who had been evacuated when the Austrian, German and Bulgarian forces threatened to overwhelm the country.

Missions during World War I

[edit]Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, he was appointed by the Serbian government to a mission in the United States. In 1915, as an unknown Serbian monk, he toured most of the major U.S. cities, where he held numerous lectures, fighting for the union of the Serbs and South Slavic peoples.[citation needed] During Velimirović's US-campaign occurred the great retreat of the Serbian Army through the mountains of Albania. He embarked home in 1916; as his country was now in enemy hands, he went to Britain instead. Not only did he fulfill his mission, but he was also awarded a Doctorate of Divinity honoris causa from the University of Cambridge.[10]

He gave a series of notable lectures at St. Margaret's, Westminster, and preached in St. Paul's Cathedral, making him the first Eastern Orthodox Christian to preach at St Paul's.[11] Professor at the Faculty of Orthodox Theology Bogdan Lubardić has identified three phases in the development of Velimirovich's ideas: the pre-Ohrid phase (1902–1919), the Ohrid phase (1920–1936), and the post-Ohrid phase (1936–1956).[4]

Bishop

[edit]

In 1919, Archimandrite Nikolaj was consecrated Bishop of Žiča[10] but did not remain long in that diocese, being asked to take over the office of Bishop in the Eparchy of Ohrid (1920–1931) and Eparchy of Ohrid and Bitola (1931–1936) in southern parts of Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In 1920, for the third time, he journeyed again to the United States, this time on a mission to organize the Serbian Orthodox Diocese of North America.[12] He made another trip to the United States in 1927.[13]

German Chancellor Adolf Hitler awarded him with a civil medal in 1935 for his contribution in 1926 in renovation of the German military cemetery in Bitola.[14] In 1936, he finally resumed his original office of Bishop in the Eparchy of Žiča, returning to the Monastery of Žiča not far distant from Valjevo and Lelić, where he was born.

Detention and imprisonment in World War II

[edit]During World War II, in 1941, as soon as the German forces occupied Yugoslavia, Bishop Nikolaj was arrested by the Nazis in the Monastery of Žiča after the suspicion of contributing to the resistance. After which he was confined in the Monastery of Ljubostinja. Later he was transferred to the Monastery of Vojlovica (near Pančevo) in which he was confined together with the Serbian Patriarch Gavrilo V. On 15 September 1944, both Patriarch Gavrilo V (Dožić) and Bishop Nikolaj were sent to Dachau concentration camp, which was at that time the main concentration camp for clerics arrested by the Nazis. Both Velimirović and Dožić were held as special prisoners (Ehrenhäftlinge) imprisoned in the so-called Ehrenbunker (or Prominentenbunker) separated from the work camp area, together with high-ranking Nazi enemy officers and other prominent prisoners whose arrests had been dictated by Hitler directly.[15]

In August 1943 German general Hermann Neubacher became special emissary of the German Foreign Office for Southeastern Europe. From 11 September 1943, he was also made responsible for Albania. In December 1944 as part of a settlement of Neubacher with Milan Nedić and Dimitrije Ljotić Germans were release Velimirović and Dožić who were transferred from Dachau to Slovenia, as the Nazis attempted to make use of Patriarch Gavrilo's and Nikolaj's authority among the Serbs in order to gain allies in the anti-Communist movements.[16] Contrary to claims of torture and abuse at the camp, Patriarch Dožić testified himself that both he and Velimirović were treated normally.[17] During his stay in Slovenia, Velimirović blessed volunteers of Dimitrije Ljotić and other collaborators and war criminals such as Dobroslav Jevđević and Momčilo Đujić.[18] In the final years of World War II in the book "Reči srpskom narodu kroz tamnički prozor" he says they the Jews condemned and killed Christ "suffocated by the stinking spirit of Satan", and further he writes that "Jews proved to be worse opponents of God than the pagan Pilate", "Devil teaches them so, their father", "the Devil taught them how to rebel against the Son of God, Jesus Christ."[19] Later, Velimirović and Patriarch Gavrilo (Dožić) were moved to Austria, and were finally liberated by the US 36th Infantry Division in Tyrol in 1945.[7]

Immigration and Last Years

[edit]

After the war he never returned to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, but after spending some time in Europe, he finally immigrated as a refugee to the United States in 1946. There, in spite of his health problems, he continued his missionary work, for which he is considered An Apostle and Missionary of the New Continent (quote by Fr. Alexander Schmemann), and has also been enlisted as an American Saint[citation needed] and included on the icons and frescoes All American Saints.[20][21]

His books were banned by the Yugoslav communist government in 1947.[22]

He taught at several Eastern Orthodox seminaries such as St. Sava's Seminary (Libertyville, Illinois), Saint Tikhon's Orthodox Theological Seminary and Monastery (South Canaan, Pennsylvania), and St. Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary (now in Crestwood, New York).[citation needed]

Velimirović died on 18 March 1956, while in prayer at the foot of his bed before the Liturgy, at St Tikhon's Orthodox Theological Seminary in South Canaan Township, Wayne County, Pennsylvania, where a shrine is established in his room. He was buried near the tomb of poet Jovan Dučić at the Monastery of St. Sava at Libertyville, Illinois. After the fall of communism, his remains were ultimately re-buried in his home town of Lelić on 12 May 1991, next to his parents and his nephew, Bishop Jovan Velimirović. On 19 May 2003, the Holy Assembly of Bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church recognized Bishop Nikolaj (Velimirović) of Ohrid and Žiča as a saint and decided to include him into the calendar of saints of Holy Orthodox Church (5 and 18 March).[1][2][9]

Literary criticism

[edit]Amfilohije Radović points out that part of his success lies in his high education and ability to write well and his understanding of European culture.[23]

Literary critic Milan Bogdanović claims that everything Velimirović wrote after his Ohrid years did nothing more than paraphrase Eastern Orthodox canon and dogma. Bogdanović views him as a conservative who glorified the Church and its ceremonies as an institution.[24] Others say he brought little novelty into Eastern Orthodox thought.[25] This, however, is explained by true Orthodox thought, because, as Saint John of Damascus writes, "It is for that reason that I say (teach) nothing of what is mine. I briefly express the thoughts and words passed down by Godly and wise men."[26]

Views

[edit]Nationalism of Saint Sava

[edit]In 1935, Nikolaj held a speech on the "nationalism of Saint Sava", in which he analyzed the writings of Saint Sava. Saint-savian nationalism represents a way of life created by Saint Sava that combines Serbian nationalism and Orthodox Theodulia.[28][29][30] According to Velimirović, it includes the national church, where the base of the nationalism lies, national dynasty, national state, national education, national culture and national defense.[31]

In his speech, Velimirović theorized that the nationalism of Saint Sava was against racism and hatred, saying that:

"Those of you who fought in the First World War, you can give personal testimony of a rare sight, how our soldiers behaved towards soldiers from Africa and Asia, towards people of black and yellow race, whom the Europeans brought to the battlefield from their colonies. While the Europeans themselves were estranged from their subjects, blacks and yellow-skinned people, not wanting to eat or drink with them or stay under the same tents, until then our soldiers made friends with them, ate and drank, visited them when they were sick, helped them when they were in trouble, at their celebrations congratulated and feasted, talking to them with fingers and hands. Serbs looked at blacks as people and treated them as people. Therefore, there can be no justified objection to Saint-savian nationalism, that it is narrow and exclusive."[31]

He also stated that the three greatest values of the Serbian people are: God, King and Home.[32]

Nikolaj constructs the nationalism of Saint Sava as an evangelical platform that should serve as a model for the establishment of the national church. This nationalism, unlike nationalism that originates from the Enlightenment and secular tradition, is based on faith as a basic principle. According to Nikolaj, the nationalism of Saint Sava is firstly, evangelical, because it protects the integrity of the human person and helps its perfection, and secondly, organic, because it protects the individuality of the peoples themselves, preventing them from falling into imperialism and disintegrating into internationalism. By being established on holiness as the highest personal and ecclesiastical ideal, such evangelical nationalism, according to Nikolaj, becomes a barrier to chauvinism and exclusivity toward other nations. According to this Saint-Savian nationalism promoted by Nikolaj, all peoples on earth, regardless of blood, language and religion, are the people of God and brothers among themselves.[33] (page 230)

In his writings from the mid-1930s, Nikolaj pointed to the political deviations of good nationalism. In his article “Between Left and Right” from 1935, Nikolaj criticizes internationalism and fascism, the two most powerful movements and political orders in Europe at that time. Internationalism for Nikolaj was the negation of nation and national determination, while fascism was idolatry of one's own nation.[33] (page 229)

Views on Mihailović's Chetniks

[edit]Saint Nikolaj Velimirović and Saint Justin Popović both supported the Chetniks of Mihailović. Velimirović wrote a book called "The land of the dead" in which he expressed support for the Chetnik fight against National Socialist Germany. He held a speech on 18 July 1954 about Draža and his "Saint-savian fight".[34][clarification needed]

Allegations of antisemitism

[edit]

Several of Nikolaj Velimirović's writings and public speeches have been identified by historians as containing antisemitic rhetoric and/or hate speech directed at Jews.[35][36][37] Notably, the first written record of Velimirović's antisemitic beliefs comes over a decade before the start of World War II. In fact, the first chronicled case of Velimirović expressing antisemitic beliefs dates back to a 1927 sermon delivered in the United States.[38] From the 1927 sermon titled "A Story about the Wolf and the Lamb," Velimirović's proclamations are summarized by social psychologist Jovan Byford:

In his take on the well known Christian parable about the wolf and the lamb, Velimirović referred to "Jewish leaders in Jerusalem" at the time of the crucifixion as "wolves," whose thirst for blood of the Lamb of God was motivated by their "God-hating nationalism."[38]

Byford's summary of Velimirović's "A Story about the Wolf and the Lamb" is significant for it serves as evidence that Velimirović may have utilized biblical undertones and Christian parable as a means of 'validating' his antisemitic statements to his followers. An interview that Jovan Byford conducted with Mladen Obradović (leader of Serbian far-right political organization Obraz) may suggest that this explanation still persists among some members of Serbian Orthodox society. A contemporary defender of Velimirović's reputation and saint status, Obradović defends the antisemitic writings of Velimimirović by stating that Velimirović's words only echo what had been written in early Christian texts:[39]

You have the very words of the Lord Jesus Christ when he says to the Pharisees that they are a "brood of vipers" or that their father is the Devil; Bishop Nikolaj merely quotes the Gospels.[39]

In a speech delivered in 1936 at the Žica Monastery, Velimirović spoke out against what he perceived to be a Jewish threat to Christianity in front of a distinguished audience that included Yugoslavian Prime Minister Milan Stojadinović. Velimirović used specific lines of this speech to accuse Jews of leading a secretive, coordinated effort against Christianity and "faith in real God".[40]

Velimirović's writing in Words to the Serbian People Through the Prison Window is generally seen as the strongest evidence of the Bishop holding antisemitic beliefs. Notably, many proponents of Velimirović's ideology suggest that the work is not definitive evidence of the Bishop's true ideology and beliefs about Jews and Judaism because they claim that it was written under duress during his time at Dachau.[41] The excerpts from Velimirović's Words to the Serbian People Through the Prison Window that attract the most attention from scholars studying antisemitism are quoted in Byford as follows:

The Devil teaches them [Jews]; the Devil taught them how to stand against the son of God, Jesus Christ. The Devil taught them through the centuries how to fight against the sons of Christ, against the children of light, against the followers of the Gospel and eternal life [Christians]. [...][40] Europe knows nothing other than what Jews serve up as knowledge. It believes nothing other than what Jews order it to believe. It knows the value of nothing until Jews impose their own measure of values […] all modern ideas including democracy, and strikes, and socialism, and atheism, and religious tolerance, and pacifism, and global revolution, and capitalism, and communism are the inventions of Jews, or rather their father, the Devil.[42]

Additionally, Byford identifies the antisemitic ideology of Velimirović in the work, Indian Letters in which the figure of a Jewish woman portrays Satan.[42] Notably, this example of Velimirović's antisemitic portrayal is again linked to conspiracy as Velimirović describes the woman as standing for, "all destructive and secret associations plotting against Christianity, religion, and the state."[42]

Despite accusations of antisemitism, it is recorded that Velimirović protected a Jewish family by facilitating their escape from Nazi-occupied Serbia. Ela Trifunović (Ela Nayhaus), wrote to the Serbian Orthodox Church in 2001, claiming that she had spent 18 months hiding in the Ljubostinja monastery to which she was smuggled by Velimirović, guarded and later helped move on with false papers.[43] Historians inclined to side with the view that Velimirović's writings prove that he held antisemitic beliefs note that this one incidence of the Bishop saving a Jewish family is commonly exaggerated by pro-Velimirović groups as evidence of his universal kindness and selflessness against the several confirmed antisemitic writings tied to Velimirović.[44]

Views on Germans and Hitler

[edit]Adolf Hitler decorated Nikolaj Velimirović in 1935 for his contributions to the restoration of a German military cemetery in Bitola in 1926.[45] Some claim that the order was returned in protest at German aggression in 1941.[46] In a treatise on St. Sava's day in 1935, he supported Hitler's treatment of the German national church.[47] St Nikolaj later explained himself in a letter to the American-Canadian bishop Dionysius[48], where he stated:

"I gave a lecture at Kolarch University on the nationalism of St. Sava, in the year of Saint Sava, which was 1935, and anyone who doesn't know that would think that I mentioned the leader of the [German] people during the war. In this last case, why would the Germans arrest me from the first days - until the last? I glorified St. Sava, not Hitler. I said that St. Sava, as a saint, genius and hero of the Serbian people, created the Serbian national church 700 years ago, and united all the Serbian people in that church. A work that has not been repeated anywhere in the West. Pascal tried in the 16th century to create a national Gallican church for the French, but failed.

St. Nikolaj criticized the secularization of Germany, called the ideology of fascism the “European evil,” and referred to Hitler as the “Viennese painter” and “Satanic evil.”[49]

In spite of accusations of collaboration leveled during Communist times, some of Velimirović's actions and writings were directed against the Germans who got suspicious of him when he supported the coup in April 1941.[50] They suspected him of collaborating with the Chetniks and formally arrested him and kept him first in Ljubostinja Monastery in 1941 and then in 1944 in Dachau concentration camp. In Dachau, he was imprisoned in Ehrenbunker, together with other clergy and high-ranking Nazi enemy officers, and was allowed to wear his own religious clothes, having access to the officer's canteen. It is claimed that he was never tortured and had access to officers' medical services. Contrary to the reports that Velimirović was liberated when the Americans' 36th Division reached Dachau, both he and Patriarch Dožić were actually released in November 1944, having spent three months in the camp. They travelled to Slovenia, from where Velimirovic continued first to Austria then to United States.[51]

Views on Ljotić

[edit]Velimirović had a high opinion of Dimitrije Ljotić, a Serbian fascist politician and German collaborationist.[52] However, he never supported him politically.[53] There were many examples in Velimirović's letters written during the 1950s, in which he wanted to distance himself from the actions of the Ljotić's pro-fascist movement Zbor in the emigration, which he labelled as “national godlessness” in order to differentiate it from the communist godlessness. Velimirović's sympathies for religiosity of Dimitrije Ljotić, the leader of Zbor movement, encouraged Ljotić's adherents to interpret Velimirović's words as the support for Zbor's political goals, not only after World War One, but also in the interwar period. On several occasions, Velimirović himself tried to prevent Ljotić's political adherents to usurp and exploit the publishing house “Svečanik” in Munich founded by Velimirović for their political goals. Therefore, it would not be difficult to imagine that some of them forged Velimirović's writings by interpolating the political agenda of the Zbor movement.[53]

Legacy

[edit]

A monastery is named after him in China, Michigan.[citation needed]

Porfirije, Serbian Patriarch stated that he is one of the three most notable Serb theologians to be recognized internationally.[54] Velimirović is included in the book The 100 most prominent Serbs.[55] In 2023 in Belgrade, on Ascension Day, the city's patronal feast, his relics were carried in front of a procession attended by more than 100,000 people, making it the largest procession in the history of Belgrade.[56]

Selected works

[edit]- Моје успомене из Боке (1904) (My memories from Boka)

- Französisch-slavische Kämpfe in der Bocca di Cattaro (1910)

- Beyond Sin and Death (1914)

- Christianity and War: Letters of a Serbian to His English Friend (New York, 1915)

- The New Ideal in Education (1916)

- The Religious Spirit of the Slavs (1916)

- The Spiritual Rebirth of Europe (1917)

- Orations on the Universal Man (1920)

- Молитве на језеру (1922)

- Thoughts on Good and Evil (1923)

- Homilias, volumes I and II (1925)

- Читанка о Светоме краљу Јовану Владимиру ()

- The Prologue from Ohrid Archived 19 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine (1926)

- The Faith of Educated People (1928)

- The War and the Bible (1931)

- The Symbols and Signs (1932)

- The Chinese Martyrs by Saint Nikolai Velimirovich (Little Missionary, 1934 — 1938)

- Emmanuel (1937)

- Теодул (1942)

- The Faith of the Saints (1949) (an Eastern Orthodox Catechism in English)

- The Life of Saint Sava (Zivot Sv. Save, 1951 original Serbian language version)

- Cassiana - the Science on Love (1952)

- The Only Love of Mankind (1958) (posthumously)

- The First Gods Law and the Pyramid of Paradise (1959) (posthumously)

- The Religion of Njegos (?)

- Speeches under the Mount (?)

- Vera svetih (?) (Faith of the holy)

- Indijska pisma (?) (Letters from India)

- Iznad istoka i zapada (?) (Above east and west)

- izabrana dela svetog Nikolaja Velimirovića (?) (Selected works of saint Nikolaj Velimirović)

References

[edit]- ^ a b The Autonomous Orthodox Metropolia of Western Europe and the Americas (ROCOR). St. Hilarion Calendar of Saints for the year of our Lord 2004. St. Hilarion Press (Austin, TX). p.22.

- ^ a b "03 May 2017". Eternal Orthodox Church Calendar. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ "Life of St. Nikolai Velimirovich". Orthodoxinfo.com. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d Markovich, Slobodan G. (2017). "Activities of Father Nikolai Velimirovich in Great Britain during the Great War". Balcanica (48): 143–190. doi:10.2298/BALC1748143M. hdl:21.15107/rcub_dais_5544.

- ^ The Living Church. Morehouse-Gorham Company. 1946.

- ^ Milorad Tomanić, Srpska crkva u ratu i ratovi u njoj, p44

- ^ a b c d "Saint Nikolaj (Velimirovic) - Canadian Orthodox History Project". orthodoxcanada.ca. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ Milorad Tomanić, Srpska crkva u ratu i ratovi u njoj, p45

- ^ a b Repose of St Nicholas of Zhicha. OCA - Lives of the Saints.

- ^ a b Bank, Jan and Gevers, Lieve. Churches and Religion in the Second World War, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016, ISBN 9781472504807, p. 267

- ^ Markovich, Slobodan G. (2017). "Activities of Father Nikolai Velimirovich in Great Britain during the Great War". Balcanica (XLVIII): 143–190. doi:10.2298/BALC1748143M. hdl:21.15107/rcub_dais_5544.

- ^ The Outlook Magazine carried a story about Bishop Nikolaj after visiting the United States in their 23 February 1921 issue (pp. 285–86)

- ^ Living Age, Vol. 335-36, 1928-29

- ^ Byford 2005, p. 32.

- ^ Leisner, Karl. Priesterweihe und Primiz im KZ Dachau, pg. 183, LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster, 2004; ISBN 3825872777, 9783825872779

- ^ Byford 2005, p. 35.

- ^ Glasnik Pravoslavne Crkve, July 1946, pp 66-67. Also in Dožić G., Memoari patrijarha srpskog Gavrila (Beograd: Sfairos 1990), entries for December 1944.

- ^ Byford 2005, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Byford 2005, pp. 30–31.

- ^ "Conciliar Press - All American Saints - 8 x 10 Icon". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ^ "All Saints of North America | Flickr - Photo Sharing!". Flickr. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ Randelić, Zdenko (2006). Hrvatska u Jugoslaviji 1945. – 1991: od zajedništva do razlaza. Zagreb: Školska knjiga. pp. 156–157. ISBN 953-0-60816-0. 978-953-0-60816-0.

- ^ Radović, A. "Bogočovječanski etos Valdike Nikolaja" in Jevtić, A., Sveti Vladika Nikolaj Ohridski i Žicki (Kraljevo, Žiča 2003)

- ^ Bogdanovic, M, Knjizevene Kritike I (Beograd 1931), p. 78.

- ^ Djordjevic, M, "Povratak propovednika", Republika No. 143-144, July 1996.

- ^ "Saint Nicodemos Publications". Saintnicodemos.org. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "Lelić, zadužbina svetog Nikolaja Žičkog". P-portal (in Croatian). 3 May 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ https://www.scribd.com/doc/30345462/Vladika-Nikolaj-Velimirovic-Nacionalizam-Svetog-Save

- ^ https://svetosavlje.org/srpski-narod-kao-teodul/

- ^ Шијаковић, Богољуб (2019). Светосавље и филозофија живота [Saintsavaism & philosophy of life]. Нови Сад: Православна реч. ISBN 978-86-83903-98-6.

- ^ a b "Vladika Nikolaj Velimirovic - Nacionalizam Svetog Save". 1935.

- ^ "ВЛАДИKА НИKОЛАЈ ВЕЛИМИРОВИЋ: Ово су 3 највеће вредности српског народа! – Наука и култура". naukaikultura.com.

- ^ a b Cvetković, Vladimir; Bakić, Dragan, eds. (2022). Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović: Old Controversies in Historical and Theological Context (PDF). Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences.

- ^ "Zemlja Nedođija - Vladika Nikolaj Velimirović".

- ^ Sekelj, L. (1997). "Antisemitism and Jewish Identity in Serbia". Analysis of Current Trends in Antisemitism. Hebrew University of Jerusalem., acta no. 12

- ^ Byford, J. (2004). "From traitor to saint in public memory: the case of Serbian Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović´". Analysis of Current Trends in Antisemitism. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem., acta no. 22

- ^ Kostic, S. (29 May 2003). "Sporno slovo u crkvenom kalendaru". Vreme No. 647.

- ^ a b Byford 2008, p. 43.

- ^ a b Byford 2008, p. 175.

- ^ a b Byford 2008, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Byford 2008, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Byford 2008, p. 45.

- ^ Свети Владика Николај Охридски и Жички, (Holy Bishop Nikolaj of Ohrid and Žiča)(Žiča Monastery, Kraljevo 2003), p. 179

- ^ Byford 2008, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Byford 2008, p. 47.

- ^ See letter "Poveli ste se za mišljenjem Filipa Koena" in Danas, 27 July 2002.

- ^ Radić, R. Država i verske zajednice 1945-1970 (Institut za noviju istoriju Srbije; Beegrad 1970), p. 80

- ^ https://www.in4s.net/vladika-nikolaj-velimirovic-oklevetani-svetitelj/

- ^ https://dais.sanu.ac.rs/bitstream/handle/123456789/14048/bitstream_56093.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- ^ Jevtić, A., "Kosovska misao i opredeljenje Episkopa Nikolaja", Glas crkve, 1988, No. 3, p. 24

- ^ Byford 2008, p. 55.

- ^ Subotic, D., Episkop Nikolaj i Pravoslavni Bogomoljacki Pokret (Nova Iskra, beograd 1996), p. 195 et al. Also Byford, J, "Potiskivanje i poricanje antisemtizma", Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava, Beograd, Ogledi, Br. 6, p. 33 and Martić, M., 1980, "Dimitrije Ljotić and the Yugoslav National Movement Zbor, 1935-1945" in "East European Quarterly," Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 219-39.

- ^ a b "Bishop Nicholai, Hitler and Europe: Controversies" (PDF). The Nicholai Studies: International Journal for Research of Theological and Ecclesiastical Contribution of Nicholai Velimirovich. 1 (1): 71. 2021. doi:10.46825/nicholaistudies/ns.2021.1.1.

- ^ Beta, Agencija (6 March 2021). "Patrijarh Porfirije o episkopu Atanasiju: "I kada smo sa njim igrali fudbal i kada nas je vodio na Svetu Goru bio je tamo gde i sveti oci"". Nedeljnik. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ 100 najznamenitijih Srba (in Serbian). Princip. 1993. ISBN 978-86-82273-01-1.

- ^ "Largest procession in history of Belgrade held with relics of St. Nikolai (Velimirović)". OrthoChristian.Com. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Vuković, Sava (1998). History of the Serbian Orthodox Church in America and Canada 1891–1941. Kragujevac: Kalenić.

- Byford, J.T. (2004). Canonisation of Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović and the legitimisation of religious anti-Semitism in contemporary Serbian society. East European Perspectives, 6 (3)

- Byford, J.T. (2004). From ‘Traitor’ to ‘Saint’ in Public Memory: The Case of Serbian Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović. Analysis of Current Trends in Antisemitism series (ACTA), No.22.

- Byford, J.T. "Canonizing the 'Prophet' of antisemitism: the apotheosis of bishop Nikolaj Velimirović and the legitimation of religious anti-semitism in contemporary Serbian society", RFE/RL Report, 18 February 2004, Volume 6, Number 4

- Byford, Jovan (2005). Potiskivanje i poricanje antisemitizma : sećanje na vladiku Nikolaja Velimirovića u savremenoj srpskoj pravoslavnoj kulturi. Belgrade: Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava u Srbiji. ISBN 978-8-67208-117-6.

- Byford, Jovan (2008). Denial and Repression of Antisemitism: Post-communist Remembrance of the Serbian Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-9-63977-615-9.

- Byford, Jovan (2011). "Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović: "lackey of the Germans" or a "Victim of Fascism"?". In Ramet, Sabrina P.; Listhaug, Ola (eds.). Serbia and the Serbs in World War Two. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 128–152. ISBN 978-0-230-27830-1.

- Cohen, Philip J. (1996). Serbia's Secret War: Propaganda and the Deceit of History. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-760-7.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch