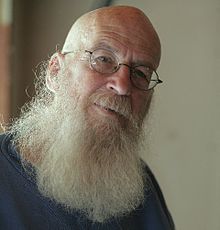

Nick Herbert (physicist)

Nick Herbert | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 7, 1936 |

| Alma mater | Saint Charles Preparatory School, Ohio State University, Stanford University |

| Spouse | Betsy Rose Rasumny (deceased 2002) |

Nick Herbert (born September 7, 1936) is an American physicist and author, best known for his book Quantum Reality.

Biography

[edit]Herbert studied engineering physics at The Ohio State University, graduating in 1959. He received a Ph.D. in physics from Stanford University in 1967 for work on nuclear scattering experiments. After a one-year teaching job at Monmouth College in Illinois, Herbert held a number of posts in industry. The most illustrious of these was senior physicist at Memorex Corporation in Santa Clara, California, where he developed new magnetic materials, as well as magnetic, electrostatic and optical measuring devices, and carried out theoretical work on Lorentz microscopy. He was also senior physicist at Smith-Corona Marchant Corporation in Palo Alto, California where he developed a new theory of xerographic process and worked on early developments in ink jet printing.[1][2]

While employed in industry, Herbert was part of the Fundamental Fysiks Group at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, founded in May 1975 by Elizabeth Rauscher and George Weissmann.[3] The group's initial interest was in the interpretation of quantum mechanics, the EPR paradox, and Bell's inequality, and members pursued also diverse interests that lay outside of mainstream physics, exploring psychedelic drugs, psi phenomena, the nature of consciousness, and speculative connections of these areas with quantum physics. During the 1970s and 1980s, Herbert and Saul-Paul Sirag organized a yearly Esalen Seminar on the Nature of Reality, bringing together participants to discuss the interpretation of quantum mechanics.[4] With Richard Shoup of Xerox PARC, Herbert constructed a "Metaphase Typewriter", a "quantum operated" device whose purpose was "to communicate with disembodied spirits".[1] Despite many tests, including an attempt to contact the spirit of Harry Houdini on the hundredth anniversary of his birth, the group reported no success with the device.[5]

Herbert supports a holistic interpretation of quantum physics.[6] He has argued for "quantum animism" in which mind permeates the world at every level.[7] Werner Krieglstein wrote regarding his quantum animism:

Herbert's quantum animism differs from traditional animism in that it avoids assuming a dualistic model of mind and matter. Traditional dualism assumes that some kind of spirit inhabits a body and makes it move, a ghost in the machine. Herbert's quantum animism presents the idea that every natural system has an inner life, a conscious center, from which it directs and observes its action.[8]

In 1981, Herbert proposed FLASH, a scheme for sending signals faster than the speed of light using quantum entanglement.[9] Of this proposal, quantum computing pioneer Asher Peres wrote, "I was the referee who approved the publication of Nick Herbert’s FLASH paper, knowing perfectly well that it was wrong. I explain why my decision was the correct one, and I briefly review the progress to which it led."[10] Chief among the results that Peres claimed stemmed from a refutation of Herbert's proposal was the no-cloning theorem, proved by Wootters, Zurek, and Dieks.[11]

Books

[edit]- Quantum Reality: Beyond the New Physics. New York: Doubleday, 1985.

- Faster Than Light: Superluminal Loopholes in Physics. New York: Dutton, 1988.

- Elemental Mind: Human Consciousness & the New Physics. New York: Dutton, 1995.

- Alice Zwischen Den Welten (with Bill Shanley). DVA, 1999.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Herbert.

- ^ Kaiser 2011, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Kaiser, David. How the Hippies Saved Physics: Science, Counterculture and the Quantum Revival. W. W. Norton & Company, 2011, pp. xv–xvii, 43ff.

- ^ Kaiser 2011, p. 116.

- ^ Kaiser 2011, p. 88.

- ^ "HOLISTIC PHYSICS - OR - AN INTRODUCTION TO QUANTUM TANTRA". southerncrossreview.org.

- ^ Graham Harvey Animism: respecting the living world 2005, p. 190

- ^ Werner J. Krieglstein Compassion: a new philosophy of the other 2002, p. 118

- ^ Herbert 1982.

- ^ Peres. "How the no-cloning theorem got its name". arXiv:quant-ph/0205076.

- ^ Peres 2003.

Sources

[edit]- Herbert, Nick (1982), "FLASH—A superluminal communicator based upon a new kind of quantum measurement", Foundations of Physics, 12 (12): 1171–1179, Bibcode:1982FoPh...12.1171H, doi:10.1007/BF00729622

- Herbert, Nick. "Nick Herbert". Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- Kaiser, David (2011), How the Hippies Saved Physics: Science, Counterculture, and the Quantum Revival, W. W. Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-07636-3

- Peres, Asher (2003), "How the No-Cloning Theorem Got its Name", Fortschritte der Physik, 51 (45): 458–461, arXiv:quant-ph/0205076, Bibcode:2003ForPh..51..458P, doi:10.1002/prop.200310062

- Interview with Nick Herbert: MAVERICKS OF THE MIND: NEW MILLENIUM CONVERSATIONS

External links

[edit]- Nick Herbert with Dr. Jabir website

- Nick Herbert blog

- Chasing the Quantum Tantra (Scientific American 2018)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch